Haemophilia

Haemophilia A

Clinical features

As factor VIII is a critical component of the blood coagulation pathway (see p. 12), low levels predispose to recurrent bleeding. The likelihood of bleeding can be roughly predicted from the factor VIII level, which may be expressed as units/dL or as percentage activity (Table 36.1).

Table 36.1

Factor VIII level and clinical severity of haemophilia

| Factor VIII level | Clinical severity |

| Less than 2 units/dL | Severe: frequent spontaneous bleeds into joints and muscles |

| 2–5 units/dL | Moderate: some spontaneous bleeds, bleeding after minor trauma |

| 5–45 units/dL | Mild: bleeding only after significant trauma or surgery |

Bleeding in haemophilia

The disease usually becomes apparent when the child begins to crawl. Severely affected patients not receiving prophylactic treatment experience 30–50 bleeding episodes each year. The most common problems are spontaneous bleeds into joints, often elbows or knees, although any joint can be involved. Patients may develop particular target joints which bleed frequently. They often have an innate feeling that a bleed has started prior to any objective signs. Recurrent or inadequately managed joint bleeds lead to chronic deformity of the joint with swelling and pain (Fig 36.1).

Fig 36.1 Chronic knee damage in severe haemophilia A.

(b) Shows bilateral osteoporosis, narrowing of the joint space and joint deformity.

Bleeding may also afflict deep-seated muscles, often the flexor muscle groups. If ignored, the enlarging haematoma can compress adjacent nerves and vessels with serious consequences (Fig 36.2). Haematuria is not unusual and, until recently, intracranial bleeding was the most common cause of death in haemophilia.

Management

Treatment of bleeding

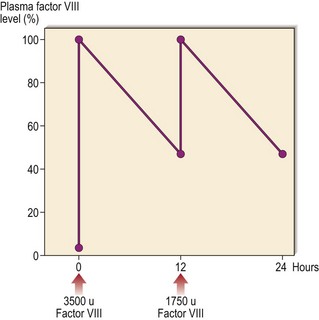

Most haemophiliac patients require replacement therapy with factor VIII concentrate and this is often self-administered at home when a bleed occurs (‘on demand’ treatment). The dose and duration of treatment depends on the patient’s size and the locality and magnitude of the bleed. One unit of factor VIII is the amount contained in 1 mL of normal plasma. For spontaneous haemarthroses it is sufficient to raise the factor VIII level to 30% of normal; in a 70 kg man this entails a dose of around 1000 units. More serious bleeding or surgery requires levels of 70–100% maintained until the risk subsides (Fig 36.3). Factor VIII products undergo processing to maximise quality, purity and viral safety. Plasma-derived factor VIII is being increasingly replaced by recombinant factor VIII. Third-generation recombinant factor VIII is free of any animal or human protein. Prophylactic (alternate day) recombinant factor VIII treatment in children eradicates bleeding and improves quality of life. Periods of ‘secondary prophylaxis’ may be considered in older patients with problematic joint bleeds.

Fig 36.3 Typical response to factor VIII infusion in a patient with severe haemophilia.

An infusion of 3500 units will increase the level to around 100% in a 70 kg man. As factor VIII has a half-life of 12 hours, the level falls to 50% at this time – an infusion of 1750 units increases the level from 50 to 100%.

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is a potentially curative treatment for haemophilia and is discussed on page 103.

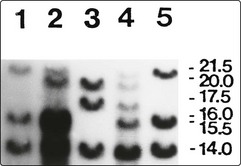

The carrier state and genetic counselling

Female carriers are generally asymptomatic but some will have low enough levels of factor VIII (10–30%) to cause excessive bleeding after trauma. In families with inversion of the factor VIII gene (see above), first-generation molecular biology methods have been used in carrier and prenatal diagnosis (Fig 36.4). The more recent development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based screening and sequencing technology has allowed identification of the mutation in nearly all patients with haemophilia A. Large databases of the known mutations are freely available.