Haemolytic anaemia II – Acquired disorders

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

Classification

Table 15.1 shows a simple approach to the classification of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. The disease can be divided into ‘warm’ and ‘cold’ types depending on whether the antibody reacts better with red cells at 37°C or 0–5°C. For each of these two basic types of autoimmune haemolysis there are a number of possible causes and these can be incorporated into the classification. A diagnosis of autoimmune haemolysis may precede diagnosis of the causative underlying disease.

Table 15.1

Classification of the autoimmune haemolytic anaemias

| Warm AIHA (usually IgG) | |

| Primary (idiopathic) | |

| Secondary | Lymphoproliferative disorders |

| Other neoplasms | |

| Connective tissue disorders | |

| Drugs | |

| Infections | |

| Cold AIHA (usually IgM) | |

| Primary (cold haemagglutinin disease) | |

| Secondary | Lymphoproliferative disorders |

| Infections (e.g. mycoplasma) | |

| Paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria1 |

1Caused by a biphasic polyclonal IgG antibody (Donath–Landsteiner).

Clinical presentation and management

Warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

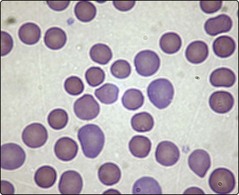

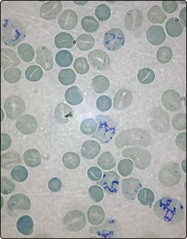

Warm AIHA (Figs 15.1 and 15.2) is the most common form of the disease. The red cells are coated with either IgG alone, IgG and complement, or complement alone. Premature destruction of these cells usually takes place in the reticuloendothelial system. Approximately half of all cases are idiopathic but in the other half there is an apparent underlying cause (Table 15.1). The autoantibody is produced by polyclonal B-cells and is usually non-specific with reactivity against basic membrane constituents present on virtually all red cells. Patients present with the clinical and laboratory features of haemolysis discussed in the last section. Splenomegaly is a frequent examination finding in severe cases. The most characteristic laboratory abnormality in warm AIHA is a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) sometimes known as the Coombs’ test (p. 83). A major priority in management is the identification and treatment of any causative disorder. It is particularly important to stop an offending drug – cephalosporin antibiotics are most commonly implicated. Where the haemolysis itself requires treatment, steroids are normally used (e.g. prednisolone 1–2 mg/kg daily). In idiopathic AIHA most patients will respond to steroids with a significant rise in haemoglobin and diminished clinical symptoms. However, the disease is usually controlled rather than cured and relapses often occur when steroids are reduced or stopped. Where refractoriness to steroids develops, splenectomy is usually indicated. Other immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. azathioprine, ciclosporin), intravenous immunoglobulin, cytotoxic agents and the monoclonal antibody rituximab may all be helpful in difficult cases.

Cold autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

In cold AIHA the antibody is generally of IgM type with specificity for the I red cell antigen. It attaches best to red cells in the peripheral circulation where the blood temperature is lower. As is seen in Table 15.1, this kind of haemolysis can occur in the context of a monoclonal (i.e. malignant) proliferation of B-lymphocytes in the so-called ‘idiopathic cold haemagglutinin syndrome’ or in a variety of lymphomas. The other major cause is infection.

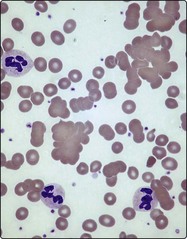

The severity of haemolysis varies and agglutination (clumping) of red cells (Fig 15.3) may cause circulatory problems such as acrocyanosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon and ulceration. The haemolysis, where longstanding, is often worse in the winter. On occasion red cell destruction is intravascular due to direct lysis by activated complement. Where this occurs free haemoglobin is released into the plasma (haemoglobinaemia) and may appear in the urine (haemoglobinuria), giving it a dark colour. Cold AIHA arising from infection is usually self-limiting. Where it is chronic the mainstay of treatment is keeping the patient warm, particularly in the extremities. In forms associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, cytotoxic drugs (e.g. chlorambucil) or rituximab may be helpful. Steroids are generally ineffective.

Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia

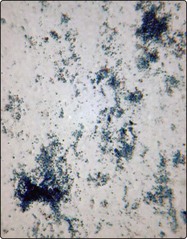

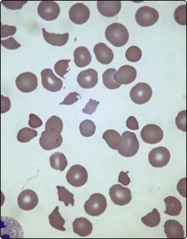

Collectively, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA) is one of the most frequent causes of haemolysis. The term describes intravascular destruction of red cells in the presence of an abnormal microcirculation. There are many causes of MAHA (Table 15.2) but common triggers are the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), abnormal platelet aggregation and vasculitis. Characteristic laboratory findings include red cell fragmentation in the blood film (Fig 15.4) and the coagulation changes seen in DIC (see p. 79). Two specific syndromes merit brief description.

Table 15.2

Causes of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia

1Some authorities believe that HUS and TTP are effectively a single disorder TTP-HUS.

Fig 15.4 Blood film in microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia.

Fragmented red cells and thrombocytopenia.

Other acquired haemolytic anaemias

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) (Fig 15.5) is a rare example of acquired haemolysis caused by an intrinsic red cell defect. In this clonal disorder arising from a somatic mutation in the PIG-A gene in a stem cell, the mature blood cells have faulty anchoring of several proteins to membrane glycophospholipids containing phosphatidylinositol. Clinical features are highly variable and include intravascular haemolysis, pancytopenia and recurrent thrombotic episodes, including portal vein thrombosis. There is coexistent marrow damage and PNH is often associated with aplastic anaemia and may even terminate in acute leukaemia. The traditional diagnostic test exploited the cell’s unusual sensitivity to complement lysis (Ham test). Flow cytometry is now used to show the cells’ characteristic lack of certain surface proteins (CD55, CD59) and to quantitate the PNH clone. Management is largely supportive with blood transfusion and anticoagulation. More recently, eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody blocking activation of terminal complement, has been given to reduce haemolysis and the risk of thrombosis. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only curative option but is used very selectively (e.g. in severe marrow failure).