Problem 20 Haematuria in a 60-year-old man

His urine microscopy shows >1000 red blood cells, and culture had no growth. Haemoglobin is 132 g/L, creatinine 128, and liver function tests are normal. A representative slice from the contrast-enhanced CT scan is shown in Figure 20.1.

Tumour stage is the most important prognostic factor (Table 20.1).

Table 20.1 Prognosis according to tumour stage

| Renal Tumour | 5-Year Survival |

|---|---|

| Confined to kidney | 75–90% |

| Invades perinephric fat, adrenal, renal vein, IVC | 50–70% |

| Lymph node involvement | 30% |

| Distant metastases | 5% |

Six months later the patient is reviewed. He has no urinary symptoms, has a good appetite, stable weight and enjoys being back at work. His creatinine is 108, and a CT chest, abdomen and pelvis is performed. This shows enlarged subcarinal nodes. The solitary right kidney appears normal and there are no pulmonary lesions (Figure 20.2).

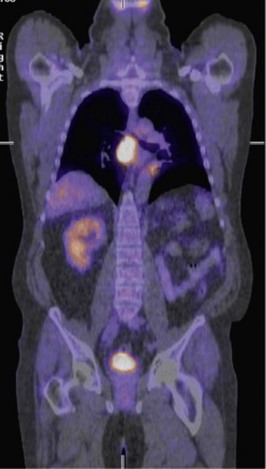

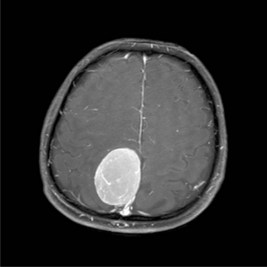

This location is very difficult to sample due to its deep, central location, and a percutaneous biopsy is not possible. A transtracheal needle aspirate via a bronchoscopy is performed and only yields inflammatory material. A PET/CT scan is arranged and shows the following (Figure 20.3).

Answers

A.1 Haematuria can arise from upper or lower urinary tract causes.

Revision Points