Haematology in the elderly

Anaemia

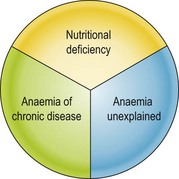

Anaemia is a common clinical problem in the elderly. The prevalence rises rapidly after 50 years and approaches 20% in people aged over 80 years. In general, one third of cases will have an identifiable nutritional deficiency (iron, vitamin B12 or folate) (Fig 46.1). Where iron deficiency is the cause of anaemia it is often secondary to gastrointestinal blood loss, and underlying bowel pathology (e.g. colonic carcinoma) should be excluded. Another third of cases have the anaemia of chronic disease. These patients have an obvious chronic inflammatory condition (see p. 36) and will often have a measurable acute phase response (e.g. elevated C-reactive protein). In the final third of elderly patents, there is no clear cause for the anaemia (sometimes termed ‘anaemia unexplained’). This entity is a diagnosis of exclusion and has been the focus of much recent interest. A few cases may be explained by myelodysplastic syndrome or other rarer causes of anaemia but it is probably mainly due to a combination of age-related suppression of erythroid colony formation, insensitivity to erythropoietin and impaired iron utilisation.

Thrombosis and anticoagulation

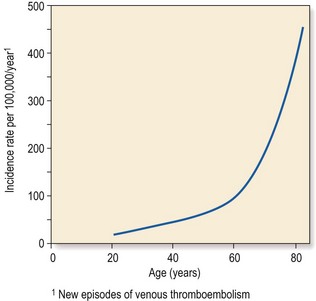

Old age is a relatively hypercoagulable state. Ageing leads to increased plasma levels of fibrinogen and various clotting factors and delayed fibrinolysis. The incidence of both arterial and venous thrombosis increases with age (Fig 46.2). Advanced age is not in itself a contraindication to the use of anticoagulant therapy – older patients may derive the greatest benefit – but there are particular considerations. Patients over 60 years usually require lower doses of vitamin K antagonists to maintain a therapeutic range than younger patients. Some studies have suggested an increased risk of adverse events such as bleeding in older patients on anticoagulants. It is not clear whether this is related to age alone or the presence of comorbidity. It is sensible to monitor elderly patients more frequently. It is likely that the newer oral anticoagulants (see p. 102) will also have to be used cautiously in this group of patients.

Haematological malignancy and chemotherapy

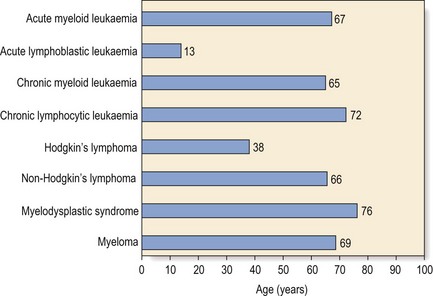

Haematological malignancy can occur at any age but most types are more common in the elderly. The median age at diagnosis for all blood neoplasms combined is around 70 years (Fig 46.3). There is a male excess except for over 80 years when more women are diagnosed. This may be because of greater female life expectancy. Some haematological malignancies in the elderly are diagnosed incidentally, are indolent, and require little or no intervention. Examples are described in other sections and include monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis and early stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Other neoplasms are aggressive and will reduce quality of life and shorten life expectancy in the absence of effective treatment.

Older patients tolerate chemotherapy less well than younger patients and they are less likely to be cured of their malignancy (Table 46.1). Changes in pharmacodynamics account for part of this reduced effectiveness and increased toxicity. Reducing the dose of chemotherapy drugs to minimise side-effects will reduce cure rates. Other factors leading to poorer outcomes in the elderly are increased comorbidity and adverse disease characteristics. For example, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukaemia have a higher incidence of poor risk cytogenetic changes compared with younger patients. They also have an increased number of significant chemotherapy side-effects including more profound myelosuppression, neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity.

Table 46.1

Guidelines for the management of chemotherapy in older cancer patients

Geriatric assessment for patients over 70 years

Adjust doses to individual GFR in patients over 65 years

Prophylactic use of G-CSF in patients over 65 years receiving regimens comparable to CHOP1

GFR: glomerular filtration rate; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.