6 Haematology and Oncology

Microcytic and macrocytic anaemia

Assessment

The impact of anaemia on an individual is variable and will depend on:

Symptoms are non-specific and clinical signs easily overlooked:

Investigations

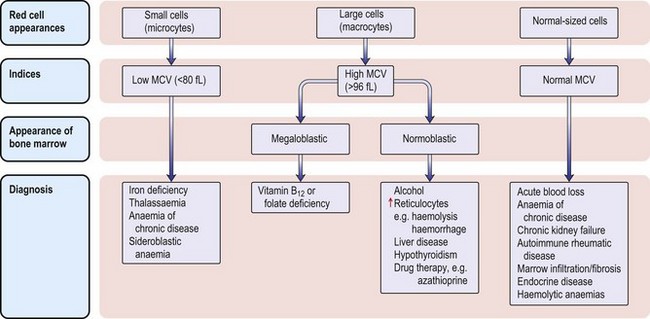

The classification of anaemia (Fig. 6.1) is based on the mean red cell volume (MCV; NR 76–96 fL).

What is the reason for her anaemia and is it relevant to her presentation?

• Very low MCV with only moderate anaemia

• Minimal variation in red cell size (anisocytosis) and shape (poikilocytosis).

• The serum ferritin (30 µg/L) was normal, indicating normal tissue stores of iron (Note: ferritin can be high because it is an acute-phase protein that rises whenever the ESR or CRP is elevated).

The anaemia of chronic disorder, a form of functional iron deficiency, is also unlikely without an obvious underlying illness and a normal ESR.

Remember

• Ferritin is an acute-phase protein. Iron deficiency can therefore be difficult to diagnose in the presence of inflammatory disease and tissue iron stores might need to be examined directly by bone marrow aspiration

• Serum transferrin receptor assay does differentiate between these conditions (see p. 142).

β-thalassaemia trait is confirmed by measuring HBA2, which is normally < 3.4% of total haemoglobin.

Iron deficiency anaemia

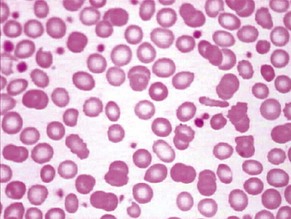

Iron deficiency anaemia (Fig. 6.2 and see p. 142) responds to treatment with oral iron supplements – ferrous sulphate 200 mg × 3 daily (or all in one dose) for 6 months – it is essential to give a full course of treatment. Lower the dose if GI symptoms occur. Parenteral therapy is required only rarely. The cause of iron deficiency is almost always blood loss and the cause must be determined.

Provan D. Mechanisms and management of iron deficiency anaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 1999;105(Suppl 1):19–26.

Case history (2)

An 81-year-old woman presents to the A&E department with recent onset congestive cardiac failure.

Make a precise diagnosis by measuring serum vitamin B12, serum and red cell folate:

• In vitamin B12 deficiency the serum vitamin B12 concentration is always reduced; in folate deficiency the red cell folate concentration is always reduced.

• Severe vitamin B12 deficiency can be associated with a low red cell folate and a normal or high serum folate. Vitamin B12 is required to polyglutamate folate, without which folic acid cannot be retained within cells.

,

Causes

• Folate deficiency? Nutritional deficiency is almost always a factor in any cause of folate deficiency, whether this is due to increased requirements (e.g. myelofibrosis, haemolysis) or to excess alcohol use. In malabsorption, e.g. coeliac disease, there is also poor dietary intake of folate.

• B12 deficiency? Most cases of vitamin B12 deficiency are due to malabsorption, either gastric (because of intrinsic factor deficiency) or intestinal (due to small bowel disease). Pernicious anaemia (antibodies against intrinsic factor) is the most common cause.

Additional investigations

• Intrinsic factor antibody assay (positive in 50% of patients with pernicious anaemia).

• Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies and/or jejunal biopsy (to exclude coeliac disease).

• Barium meal and follow-through (to exclude small bowel disease, e.g. Crohn’s disease); in a woman of this age only after the other causes have been excluded.

Many patients with moderate vitamin B12 or folate deficiency have a normal haemoglobin with a raised MCV. Vitamin assays should be performed if the clinical picture is suggestive of a deficiency picture.

• Gastrointestinal disease or surgery including glossitis, malabsorption or diarrhoea

• Neurological disease, including visual loss, a peripheral neuropathy or evidence of demyelination

• Psychiatric disorders including dementia, confusion or depression

• Malabsorption or restricted diets, including vegans and those with anorexia nervosa

• Autoimmune endocrine disease

Management

• Hypokalaemia, which can occasionally develop 1–2 days post therapy

• Reticulocyte count, which starts to increase 2–3 days after treatment and reaches a peak on days 5–7

• The haemoglobin concentration, which often falls further before starting to rise

• Stay calm! Avoid blood transfusion. Failure of the reticulocyte count and haemoglobin to rise in the predicted manner might be due to:

Anaemia due to folic acid deficiency

These patients need 6 months’ treatment with folic acid 5 mg daily after the cause (e.g. coeliac disease, see p. 51) has been defined and treated. Folic acid is, however, ineffective in the treatment of methotrexate toxicity, when folinic acid 15 mg IV daily is given.

Haemolytic anaemia

A normocytic anaemia can be due to:

The patient described is anaemic and jaundiced with splenomegaly, suggesting a haemolytic anaemia. To confirm this you need to demonstrate:

Increased red cell production

Reduced red cell lifespan

• Acholuric jaundice: unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia, urobilinogen but no bilirubin in the urine.

• Abnormal red cell morphology: this might also indicate the specific cause of the haemolytic anaemia (see below).

• Directly by radioactive isotope studies: reduced survival of 51Cr-labelled autologous red cells (only performed if diagnosis of haemolysis is in doubt).

There are many specific causes of haemolysis. The diagnosis can often be made by review of the blood film. Speak to the haematology medical staff.

Features of haemolysis on blood film

• Spherocytes: autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, hereditary spherocytosis, Clostridium welchii septicaemia, extensive burns

• Red cell fragments: leaking mechanical heart valve, disseminated malignancy

• Sickled cells: sickle-cell anaemia, sickle-cell–HbC disease

• Bitten-out red cells: glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, unstable haemoglobin, oxidative drug therapy, e.g. Dapsone

Investigations

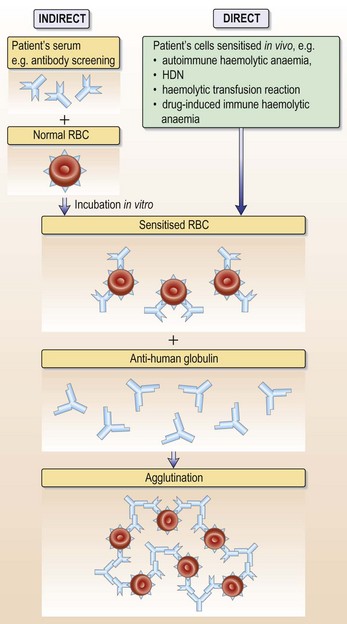

• Antibody screen and direct anti-globulin test (DAT): in autoimmune haemolytic anaemia autoantibodies to red cell membrane antigens are present in serum and on the red cell surface

• Urinary haemosiderin: positive in chronic intravascular haemolysis such as paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH, very rare) and leaking mechanical heart valves

• Flow cytometry with antibodies against CD55 and CD59 antigens for PNH

• Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase assay: common enzyme deficiency in particular ethnic groups (African, Mediterranean, SE Asian)

This patient had a strongly positive direct anti-globulin test (DAT) with anti-IgG (see Fig. 6.13, p. 129). The antibody eluted from her red cells was also present free in her serum and did not have any easily definable antigen specificity. She therefore has autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA) due to an IgG red cell autoantibody active at 37°C. AIHA can be primary or secondary. This patient is known to have CLL and has lymphadenopathy and a lymphocytosis with small, mature lymphocytes. Her AIHA is secondary to the underlying chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL); 10–15% of patients with CLL develop AIHA.

Management

• Start oral prednisolone 60 mg/day. This usually produces a remission. Corticosteroids reduce the production of antibodies and also destroy antibody coated red cells.

• Blood transfusion is necessary if the haemoglobin continues to fall. Compatibility testing is complex because the autoantibody interferes with the cross-match; the laboratory could carry out autoabsorption studies to exclude additional alloantibodies. Transfuse slowly.

• Refer patient to her Consultant in Haematology to discuss further management.

Sickle-cell disease

The examination should initially be brief until adequate pain control has been achieved.

Questions to ask patients presenting with sickle-cell crises

Any precipitating factors?

• Exposure to cold/skin chilling (might apply to this patient)

Treatment of acute painful sickle-cell crises

Analgesia

Morphine/diamorphine

• 0.1 mg/kg IV/SC every 20 minutes until pain controlled, then

• 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV/SC (or oral morphine) every 2–4 hours

• Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) when pain controlled

• NB Ask patient about previous morphine dosages. Check medical records and discharge summaries. Higher doses may be required in cases who have previously received opioids.

Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) (example for adults > 50 kg)

Supportive measures

• Hydration: aim for 3 L per 24 h – orally if possible

• Venous access is often very difficult in these patients; to conserve peripheral veins the repeated insertion of IV lines should be avoided

• IV hydration is indicated if:

• Oxygenation: aim for O2 saturation 95%

• Monitor the haemoglobin concentration daily and transfuse if it falls to 150 g/L. All transfused blood should be matched for minor blood group antigens Kell and Rh (C and e, as well as D antigens). Remember, do not use transfusions in this steady-state anaemia, in an uncomplicated painful episode and for minor surgery.

The acute chest syndrome

Treatment of acute chest syndrome

• Exchange blood transfusion to reduce the amount of HbS to < 20%

• Maintenance of oxygenation: this might include, for example, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) via a tight-fitting mask, or intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV)

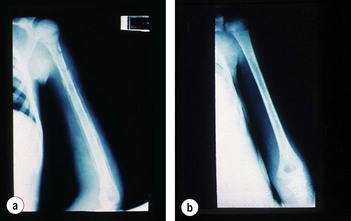

The majority of patients with a sickle-cell crisis present with severe, acute bone pain secondary to ischaemic bone marrow necrosis. Beware the patient with sickle-cell disease (SCD) who presents unwell but without pain. Such patients might have other, less common, complications of SCD, which can progress very rapidly (Figs 6.3 and 6.4).

Types of sickle-cell disease

Diagnosis in A&E/MAU

Later:

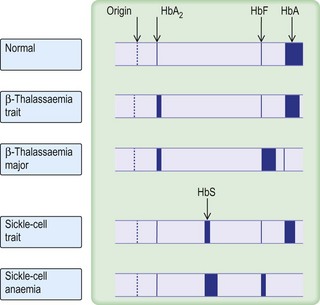

• Haemoglobin electrophoresis (Fig. 6.5) on cellulose acetate membrane (CAM) at an alkaline pH

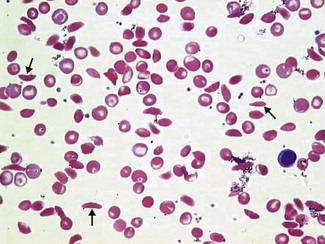

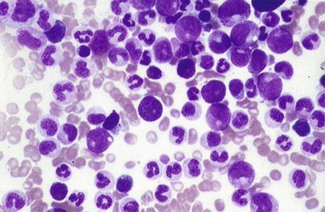

Typically, the patient will be anaemic with evidence of haemolysis (elevated bilirubin and reticulocyte count). The blood film will show sickled red cells in variable numbers (Fig. 6.6). The sickle solubility test will be positive and CAM electrophoresis or HPLC will confirm the presence of HbS ± HbC or HbD with no HbA (except in HbS/β+ thalassaemia).

Beware

• In HbSC and HbS/β+ thalassaemia the haemoglobin concentration, reticulocyte count and serum bilirubin can be virtually normal.

• The sickle solubility test is a qualitative test only and will be positive in any individual where the amount of HbS is > 10%. This will include both sickle-cell trait and sickle-cell disease.

Elevated haemoglobin (polycythaemia)

These two cases both have elevated Hb, but is their cause the same?

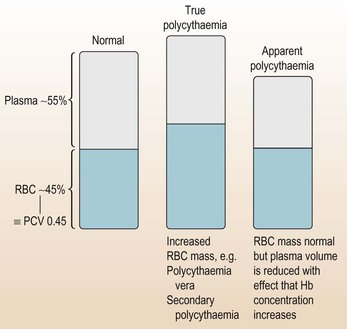

Haemoglobin (in red blood cells) is required for oxygen transport and, like most things, too much Hb has serious consequences and needs appropriate management (Fig. 6.7).

Preliminary management

• Ensure no hyperviscosity symptoms or signs:

• Ensure patient is adequately hydrated.

Having made sure that the patients are stable, the next step is to determine the cause of the high Hb concentration. Before carrying out extensive investigation, it is sensible to contact the haematology team, who will either advise on further tests or take over the patient’s care.

Information

The haematology registrar advises you to arrange some investigative tests.

Investigations

• Repeat FBC (to check the result is correct or that with some oral/IV fluid the Hb has normalised). High haematocrit.

• Biochemistry screen: renal function – is it normal? Uric acid – might be high in some types of polycythaemia.

• Blood film: these patients had elevated platelets and WBC – make sure these are normal peripheral blood cells, with no evidence of leukaemia.

• Presence of JAK 2 mutation (see Remember box).

Remember

Proposed criteria for PV

Modified from proposed revised WHO criteria for polycythaemia vera (PV).

From: Tefferi et al. Blood (2007) 110:1092. American Society of Haematology.

For diagnosis of secondary cases

• Blood gases or pulse oximetry (the latter is painless and quite adequate to exclude hypoxia only).

• CXR: emphysema, other lung pathologies.

• Abdominal ultrasound: is the spleen enlarged? Remember renal and uterine causes of polycythaemia.

• Bone marrow: not diagnostic in isolation but gives additional information.

NB It is now not necessary to do blood viscosity and red cell volume studies.

Classic features of polycythaemia vera (PV)

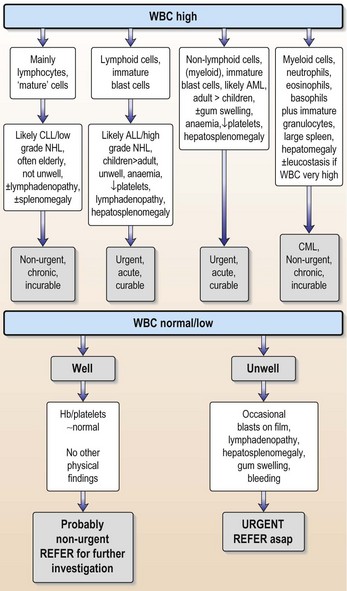

Elevated white blood cell count

There are many causes of a raised WBC (Table 6.1) and there is overlap with haematological malignancies, many of which present with WBC elevation. As a non-specialist confronted with a patient who has an elevated WBC, the key question is: does this elevation represent a haematological malignancy or is it reflecting some other process?

| Patients with haematological malignancies likely to have high WBC | Situations in which a reactive high WBC occurs |

|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | Infection |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | Corticosteroid therapy |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | Brisk GI tract bleeding |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia | ‘Stress’, e.g. postoperative |

| Lymphoma | Post splenectomy |

| Other infiltrations: myeloma, myelofibrosis |

Elevated platelet count

Immediate action

If none obvious – check again for splenomegaly, as was found in this case.

Is there a test that will confirm a primary bone marrow pathology?

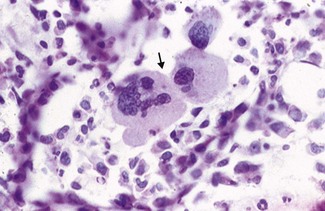

Unfortunately not. The JAK2 tyrosine kinase mutation is only present in 50% of cases (see polycythaemia vera). Bone marrow trephine biopsy can help because increases in the numbers of megakaryocytes (the cells that make platelets; Fig. 6.9) with clustering favour a diagnosis of essential thrombocythaemia (ET), but often it is a diagnosis of exclusion. Blood film examination may show marked variation in size and shape of the platelets (platelet anisocytosis; Fig. 6.10) in primary thrombocythaemia – but this is not diagnostic.

Management

• Give low-dose aspirin 75–300 mg/day (or dipyridamole if aspirin contraindicated).

• Plateletpheresis (using cell separator) if organ function threatened and need rapid reduction in platelet count.

• Oral hydroxycarbamide (e.g. 2–3 g per day for 2–3 days, dropping thereafter to 500 mg/day) to suppress bone marrow production of platelets (but beware neutropenia if dose too high). Suggested regimen: 10–30 mg/kg/day. Anagrelide and Busulfan are also used.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Definition

Case history

On examination he was pyrexial (37.8°C), anaemic and jaundiced. There was no hepatosplenomegaly.

Differential diagnosis (see Table 6.4)

Malaria is a common cause of haemolysis in patients returning from the tropics. Other evidence to suggest acute intravascular haemolysis is shown in Table 6.2.

| Test | Result |

|---|---|

| Serum bilirubin | 65 mmol/L |

| Serum haptoglobins | Undetectable |

| Serum LDH | 587 iu/L |

| Schumm’s test | Positive |

The negative isopropanol stability test excludes an inherited, unstable haemoglobin variant.

The negative DAT (or Coombs’ test) excludes immune-mediated red cell destruction.

G6PD deficiency can present as:

An acute haemolytic crisis is the most common presentation and most affected individuals are asymptomatic until this happens. Acute haemolysis occurs when an exogenous factor imposes an extra oxidative stress, which overwhelms the limited supply of NADPH in the red cells. Acute haemolysis can be precipitated by:

Many drugs (Table 6.3) have been implicated in attacks of acute haemolysis in susceptible individuals.

Table 6.3 Drugs that commonly cause acute haemolysis in patients with G6PD

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Anti-malarials | Primaquine |

| Pamaquine | |

| Chloroquine | |

| Quinine | |

| Sulfonamides | Sulfasalazine |

| Dapsone | |

| Co-trimoxazole | |

| Other antibiotics | Nitrofurantoin |

| Nalidixic acid | |

| Quinolones, e.g. ciprofloxacin | |

| Analgesics | Aspirin (> 1 g per day) |

| Miscellaneous | Vitamin K analogues |

| Naphthalene | |

| Probenecid | |

| Dimercaprol | |

| Methylene blue |

Diagnosis of G6PD deficiency

Laboratory features

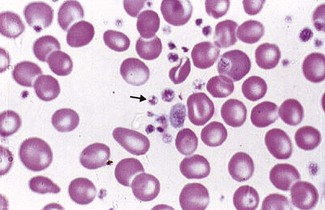

The spleen ‘bites out’ Heinz bodies, which are aggregates of oxidised methaemoglobin, from affected red cells.

Features of intravascular haemolysis

One of the isoenzymes of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is found in high concentrations in red cells and is released in red cell damage.

Rapid depletion of haptoglobin with the formation of methaemalbumin is typical of intravascular haemolysis. In the absence of other scavenging serum proteins excess haem binds to albumin and the ferrous iron is subsequently oxidised to ferric iron to give methaemalbumin and a positive Schumm’s test. The cause of the intravascular haemolysis was established by further tests, as shown in Table 6.4.

Table 6.4 Test results confirming the cause of intravascular haemolysis

| Test | Result |

|---|---|

| Haemoglobin electrophoresis | HbA + HbS |

| Direct antiglobulin test (DAT) | negative |

| Isopropanol stability test | negative |

| G6PD assay | 1.9 IU/gHb |

Remember

• Old red cells have less G6PD than young red cells and are destroyed first during a haemolytic attack

• Newly formed reticulocytes have relatively high concentrations of G6PD

• As a result of these two factors the concentration of G6PD in an affected individual may rise during an acute haemolytic episode to within the normal range

Treatment

Bleeding disorders

How can I identify the inherited disorders?

Most inherited disorders of any severity present in childhood and hence most, if not all, patients will be able to tell you about their problem. They should carry a medical card with them, identifying the problem and their haematology consultant. It should be easy to sort out these patients and get in touch with the appropriate specialist. Always take any suggestion of an inherited bleeding disorder seriously (see Figs 6.11 and 6.12).

What should I request?

You request a basic coagulation screen:

These tests form your baseline investigations or screening tests.

Acquired disorders are relatively easy because clotting times are usually notably prolonged.

Bleeding in liver disease

• Reduced synthesis of coagulation factors: the liver is the source of all coagulation factors (apart from Factor VIII).

• Associated vitamin K deficiency: coagulation proteins might be synthesised but will not be active because of vitamin K deficiency.

• Thrombocytopenia: frequently secondary to splenomegaly from portal hypertension.

• Chronic low-grade disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC): see p. 112.

• Abnormal fibrinogen synthesis: in liver disease, excess sialic acid residues are added to fibrinogen and hence an acquired dysfibrinogenaemia occurs.

The classic laboratory defects would be:

Management

• Give 10 mg vitamin K daily IV for 3 days

• For acute bleeding give 10–20 mL/kg FFP to replace all coagulation proteins

• If the fibrinogen level is low or TT prolonged, give cryoprecipitate to supply fibrinogen.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

This is the most complex of the acquired bleeding disorders.

Causes

If someone is bleeding and you always think about DIC you won’t go wrong. In many ways the long list of causes is academic when you first see the patient – but if they have got DIC you must identify the cause.

How do I make the diagnosis?

Send off all the screening tests and fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs). The pattern is:

Anti-coagulant overdosage

An obvious cause of bleeding. Don’t forget to look for warfarin/heparin usage.

Action

If due to warfarin: STOP WARFARIN

If due to heparin: STOP HEPARIN

Platelet disorders

Case history (1)

On examination she has petechiae over her trunk, arms and legs. She has no other abnormal signs.

There are multiple causes of thrombocytopenia (Table 6.5). Thrombocytopenia may be the presentation of another disorder rather than a primary platelet disorder. All patients with severe thrombocytopenia (defined as < 20 × 109/L, which produces spontaneous haemorrhage) require admission for investigation/treatment.

Table 6.5 Causes of thrombocytopenia

Remember

The list of causes (Table 6.5) is not comprehensive and excludes inherited thrombocytopenia or causes that would present in childhood.

Questions that need to be answered immediately

• Does this patient have immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)?

• Does she have acute leukaemia?

• Does she have aplastic anaemia?

• ITP: normal Hb, normal WCC, no hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy.

• Acute leukaemia (see p. 132): high WCC, abnormal white cells on film, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly (occasionally).

• Aplastic anaemia: low Hb, low WCC, no lymphadenopathy, no hepatosplenomegaly.

The diagnosis appears to be ITP. You are called back to see the patient 20 minutes later as she has had a massive haematemesis. You think the diagnosis is ITP as there are no other features to make you think it is aplastic anaemia or acute leukaemia.

Management for this patient

Learning points

• High-dose immunoglobulin elevates the platelet count by macrophage Fc receptor blockade of the reticuloendothelial system.

• Endogenous platelets usually rise after 24–48 h; the survival of exogenous platelets is improved.

• Platelet transfusion is usually not necessary in ITP except in the situation of life-threatening haemorrhage, such as in this case.

• 75% of patients respond to oral steroids but the full therapeutic effect may take 2–4 weeks to develop.

Provan D, Newland A. Fifty years of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP): management of refractory ITP in adults. British Journal of Haematology. 2002;118:933–944.

Imbach P, Crowther M. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists for primary immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:734–741.

Can he go ahead and have his hernia repair?

Avoid any NSAIDs as postop analgesia; make sure aspirin has not been taken within the last 10 days.

Thrombosis

Case history (1)

You are asked to see a 24-year-old woman who has had a life-threatening pulmonary embolus. She received fibrolytic therapy (p. 286) on the ICU. Her condition stabilised and she is now on warfarin following initial treatment with low molecular weight heparin. She wants to know why she has had a pulmonary embolus. She has a family history of DVT.

Action

• Ensure prescribed dose is being given.

• Increase dose by 10% per 24 h.

• If still low, repeat the 10% increase in heparin dose and recheck at 4-hourly intervals.

Heparin monitoring is notoriously bad in most hospitals. If IV heparin is being used it should be monitored as follows:

For how long should a patient with venous thromboembolic disease be anti-coagulated with warfarin?

The duration and target INRs for various thrombotic conditions are listed in Table 6.6.

Table 6.6 Duration and target INRs for thrombotic conditions

| Duration | INR target | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated DVT | 6 months | 2.5 |

| Complex DVT | 6 months | 2.5 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 6 months | 2.5 |

| Recurrent VTE | Indefinite | 2.5 – if the recurrent event occurs whilst taking warfarin the intensity of anti-coagulation is increased, target 3.5 |

| AF | Indefinite | 2.5 |

| Mechanical heart valves | Indefinite | 3.5 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; INR, international normalised ratio; VTE venous thromboembolism

Recurrence is much higher in patients anti-coagulated for 6 weeks rather than 6 months.

Action

This can be managed in outpatients with good nursing and laboratory support.

If the DVT is complex (i.e. iliofemoral):

There is an increasing move to outpatient management of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Dabigatran (see above) is being used instead of warfarin in some centres.

Case history (5)

You are phoned about a 36-year-old man with an acute right lower limb ischaemia due to an arterial thrombosis. He has a family history of thrombosis. There has been improvement in the ischaemic area over 24 hours. The patient is on intravenous heparin infusion and is being monitored by the vascular surgeons. The houseman wonders in view of the family history whether he should be investigated for thrombophilia. He has already sent off standard thrombophilia screen (see Investigations box, p. 118) and he asks if this is all that you need.

Action

• Stop all heparin (including heparin flush).

• Alternative forms of anti-coagulation are not required for the DVT in this woman because she is on warfarin and the INR is 2.0 and heparin was about to be discontinued.

HIT is due to an immune induction of anti-heparin/PF4 antibodies which bind to and activate platelets via a Fc receptor. This results in a prothrombotic state with low platelets. There is usually a previous history of heparin exposure.

Splenomegaly, splenectomy and hyposplenism

Case history (1)

Investigations show a normochromic normocytic anaemia with low platelets and a neutropenia.

The diagnosis is Felty’s syndrome in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

Information

Causes of splenomegaly

• Malignant haematological disease: e.g. acute or chronic leukaemia, malignant lymphoma

• Myeloproliferative disorders: e.g. polycythaemia vera, myelofibrosis (often massive)

• Haemoglobinopathies: e.g. β-thalassaemia major, haemoglobin, H, SC or E disease

• Haemolytic anaemias: e.g. hereditary spherocytosis

• Congestive splenomegaly: e.g. portal hypertension (cirrhosis)

• Inborn errors of metabolism: e.g. Gaucher’s disease

• Auto-immune rheumatic disorders: e.g. SLE, rheumatoid arthritis (Felty’s syndrome)

• Miscellaneous (rare): e.g. amyloid, tropical splenomegaly.

Pathophysiology of hypersplenism

Hyposplenism may be due to:

• Splenectomy: surgical or by irradiation

• Splenic atrophy, e.g. coeliac disease, chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Remember

Surgical splenectomy might be carried out because of:

Progress.

Case history (2)

| Blood count | Blood film |

|---|---|

| Hb 24 g/L | Polychromasia |

| MCV 76 fL | Very reduced platelets |

| WBC 30.5 × 109/L | Nucleated red cells |

| Platelets 27 × 109/L | Occasional elongated sickle cells |

| Reticulocytes 7.0% | Diplococci both within neutrophils and macrophages and free in the plasma |

Subsequent investigations demonstrated Streptococcus pneumoniae on blood culture.

Progress.

The gross splenomegaly and severe anaemia were due to acute splenic sequestration of sickled red cells within the spleen, which often accompanies pneumococcal sepsis in this age group (see p. 126).

Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) is the most feared complication of hyposplenism.

The major pathogens involved in OPSI are:

These are all encapsulated bacteria – the spleen is a vital first line of defence against encapsulated organisms. Severe infections in the hyposplenic patient can also occur in malaria and babesiosis (mosquito and tick bites, respectively) and following dog bites with Capnocytophaga canimorsus.

Prevention of OPSI depends on:

• Identification of the patient at risk

• Education of the patient about the risks of infection, dog bites and tropical travel

• Issue of a ‘post-splenectomy’ card and leaflet to the patient

• Lifelong prophylactic antibiotic therapy, e.g. penicillin V 250 mg × 2 daily

• Vaccination with a pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine and the Hib vaccine.

Blood transfusion

Never

Remember

When you request blood always make clear the urgency of the clinical situation:

• Very urgent: there is a life-threatening haemorrhage and blood is required in 1–5 min:

• Antibody screen: excludes the presence of clinically significant red cell alloantibodies in the patient’s plasma. These might result in an acute or delayed haemolytic transfusion reaction.

• Selection of appropriate donor units: wherever possible, blood of the same ABO and Rh(D) group as the patient is selected and will be negative for the appropriate antigen if an alloantibody has been identified.

• Cross-match: the patient’s plasma is reacted with the donor red cells in vitro. Incompatibility is indicated by agglutination or haemolysis.

A full compatibility procedure is always completed but this can be retrospective if the clinical demand for blood is urgent.

Action

• Stop the transfusion immediately:

• Check patient identification:

• Take samples and a relevant unit of blood to the laboratory.

• Inform haematology medical staff of the problem.

Outcome

The red cell alloantibody was identified.

Diagnosis.

Haemolytic transfusion reaction.

Monitor renal function, urine output, haemoglobin concentration and check coagulation screen.

• Insert urinary catheter and monitor urine output.

• Give IV fluids to maintain urine output (> 1.5 mL/h/kg).

• If urine output inadequate insert CVP line and give fluid challenge and diuretics (p. 223).

• Report to SHOT (Serious Hazards of Blood Transfusion), a confidential enquiry into major blood transfusion errors in the UK.

Other acute complications of blood transfusion can present with:

• Non-haemolytic (febrile) transfusion reactions. These are due to the presence of leucocyte antibodies in a multiply transfused person acting against donor leucocytes in red cell concentrate, leading to release of pyrogens. Leucocyte depleted blood is now used in many countries so the febrile reaction is not often seen.

• Urticaria or anaphylaxis: reaction to plasma proteins.

• Collapse or hypotension: major ABO incompatibility-infected blood product.

Management of massive haemorrhage

Check for failure of haemostasis

Haematological oncology

What main groups of disease are there?

• Leukaemias: can be acute (short duration, serious, rapidly fatal if not treated) or chronic. Generally have elevated WBC and other features (see below). These are marrow-/blood-based diseases.

• Lymphomas are lymph-node-based, sometimes involving blood and marrow. Some need urgent treatment and others can be sorted out at leisure.

• Myeloma is a low-grade, highly destructive disorder caused by malignant plasma cells, often presenting with bone pain, renal failure and hypercalcaemia.

The key features

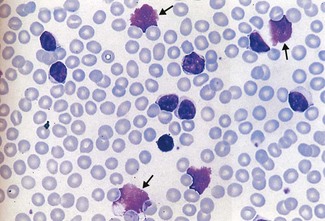

This must be chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), the most common leukaemia in adults (Fig. 6.14). It is a slowly progressive disorder and is an incidental finding or presents with an infective complication. Shingles is a fairly common presenting feature.

What tests would you arrange?

The Hb is 60 g/L, WBC 90 × 109/L and platelets are 30 × 109/L. Renal function is normal and CXR shows minimal increased shadowing at the right base.

Is this an acute or chronic disorder?

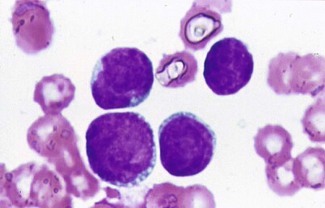

However, the technician looks at the blood film and tells you they look like blasts.

This suggests an acute leukaemia (Fig. 6.15). In a patient of this age, acute myeloid leukaemia is likeliest (if he were a child then acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is more likely).

Investigations

• Specific diagnostic tests (performed by haematology department)

• Peripheral blood film examination (are there Auer rods? If so, their presence confirms AML; these are not all that common)

• Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy

• Cell marker analysis (determines pattern of antigens on white cells)

• Cytogenetic studies on marrow blasts: several karyotypic abnormalities are diagnostic

What possible diagnoses are there?

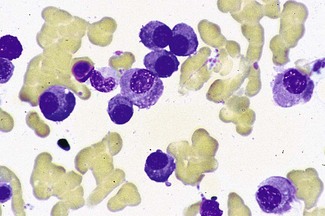

Although not in extremis, this man is ill:

• An ESR of 120 suggests serious underlying pathology (an ESR of 120 could be due to serious infection, autoimmune disease, rheumatoid disease, malignancy).

• Red cell rouleaux, renal impairment and hypercalcaemia in a patient with bone disease suggest either a primary bone disorder (such as myeloma) or possible infiltration by malignancy, e.g. carcinoma.

If outside working hours there is little else you can request. Your main objective is to treat the symptoms, e.g. rehydrate, start antibiotics if you think infection is present, correct the elevated calcium level (see p. 450). Alert the haematology team.

As soon as possible, check:

In this case the results are:

• Elevated total IgG with reduced IgA and IgM.

• Serum IgG M paraprotein (paraprotein = monoclonal immunoglobulin produced by the malignant clone of plasma cells).

• Bence–Jones protein present: kappa light chains.

• Widespread lytic lesions throughout skeleton.

• Subsequent bone marrow aspirate showed infiltration by abnormal plasma cells (Fig. 6.16).

What is the underlying diagnosis?

There are several significant findings, i.e. very high WBC, splenomegaly with weight loss and sweats. Could the patient have an underlying infection/neoplasm producing these features (i.e. reactive process)? Yes, but it is much more suggestive of an underlying primary blood disorder such as chronic myeloid leukaemia, because the white cell count is high with the whole spectrum of granulocytic cells present (Fig. 6.17). If the blood picture were ‘reactive’, a neutrophilia would be more likely.

What single investigation will confirm the diagnosis?

Cytogenetic analysis of peripheral blood white cells or bone marrow white cells.

Features suggestive of acute leukaemia/high-grade lymphoma

Features suggestive of chronic/low-grade haematological malignancy

• Previous infection (e.g. chest infection or herpes zoster)

• Abnormal peripheral blood cells: lymphocytes with abnormal morphology or immature granulocytes. Generalised lymphadenopathy present for months.

Refer all suspected patients with acute leukaemia to the haematology team as soon as possible, for specialist management.

Is it lymphoma or leukaemia? (Fig. 6.18)

• Leukaemias generally involve bone marrow and blood. Lymph nodes and other organs might be involved.

• Lymphomas originate in lymphoid tissue (lymph nodes, spleen), sometimes spill over into blood and might involve marrow (especially low-grade lymphomas).

• High-grade lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia are very similar.

• Low-grade lymphomas and chronic lymphoid leukaemias are similar.

Appelbaum FR, Rowe JM, Radich J, Dick JE. Acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology (American Society of Hematology Educational Program). 2001:62–86. Review

. The Lymphoid neoplasms. Magrath IT, Boffetta P, Potter M, eds. 3rd edn. London: Hodder Arnold; 2010.

Sawyers CL. Even better kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukaemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;362:2314–2315.

Anaemia in rheumatoid arthritis

Case history

A 53-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis was admitted for investigation of anaemia.

There are several possible causes for this anaemia:

• Bleeding (e.g. due to NSAIDs): the patient denies obvious GI bleeding. If she had been bleeding chronically her MCV would probably be reduced (iron deficiency). This woman’s MCV is normal, making chronic blood loss unlikely.

• Poor diet: can induce folate deficiency, but we know her folate level is normal.

• Autoimmune causes: e.g. pernicious anaemia (PA; she has rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and might possibly have PA, another associated autoimmune disease). However, her vitamin B12 level is normal.

• Felty’s syndrome (p. 123): RA, splenomegaly and neutropenia. This woman has no features of this disorder.

• Infiltrations, myelodysplasia (MDS): difficult to exclude these in the absence of additional information, e.g. bone marrow. In MDS and marrow infiltration due to carcinoma in the presence of reduced Hb, it is likely (but not always the case) that the blood film would show morphological abnormalities such as red cell ‘tear-drop’ cells, nucleated red cells, hypogranular neutrophils, immature white cells. This woman’s blood film simply showed RBC rouleaux.

• Renal impairment, liver disease: again, morphological abnormalities are usually present on the film, and biochemical screen will assess liver and renal function.

• Drug-induced anaemia: several mechanisms, e.g. haemolysis. There are no features suggesting this. Remember the bone marrow suppressive effect of gold and azathioprine.

This woman’s ESR was found to be > 100 mm/h with a high C-reactive protein. Her rheumatoid disease was very active (flare-up) and 3 months before admission her Hb was 110 g/L. The drop in Hb has coincided with the flare-up; a common finding, especially in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Assessment of iron status in patients with inflammatory disorders

• Ferritin: likely to be misleading for the reasons given above.

• Serum iron/TIBC: might show reduction of both in chronic disease. These tests are seldom performed now because they are unreliable. Ferritin is the preferred assay.

• Bone marrow: will determine iron status, but is expensive, painful and to be avoided if possible.

• Serum transferrin receptor assay: number of transferrin receptors on red cells rises in iron deficiency but remains normal in secondary anaemia. This test is replacing bone marrow aspirate in diagnosis of iron deficiency in patients such as this.

This woman had normal transferrin receptor levels, confirming anaemia of chronic disease. She failed treatment with sulfasalazine and methotrexate. She was therefore treated with Etanercept, a fully humanised p75 TNF α receptor IgG fusion protein subcutaneously, with a good response in her joints and the ESR. She is now attending the Rheumatology Clinic for follow-up.

Anaemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Anaemia in liver disease

Complex and multifactorial

Patients with chronic liver failure generally have moderate anaemia.

Vitamin B12 levels are normal or high; folate levels are often low, owing to poor dietary intake.

• Bleeding produces a hypochromic, microcytic picture.

• Alcohol causes macrocytosis, sometimes with leucopenia and thrombocytopenia due to bone marrow suppression.

• Hypersplenism results in pancytopenia.

• Cholestasis can often produce abnormal-shaped cells and also deficiency of Vitamin K.

• Haemolysis accompanies acute liver failure and jaundice.

• Aplastic anaemia is present in up to 2% of patients with acute viral hepatitis.

• A raised serum ferritin with transferrin saturation (> 60%) is seen in hereditary haemochromatosis.

Anaemia in cancer

Anaemia of chronic disorder: pathophysiology

She has a raised total white cell count with nucleated red cells and immature granulocytes seen on the blood film. This is a leucoerythroblastic picture; such cells are normally confined to the bone marrow. Bone marrow infiltration by disseminated malignancy disrupts the normal mechanisms controlling release of haemopoietic cells into the blood.

Leucoerythroblastic anaemia

However, review of the blood film in this patient reveals that the thrombocytopenia is spurious – platelets are clumped on the blood film. Platelet clumping is a common phenomenon related to the EDTA anti-coagulant that blood is collected into.

Infection/sepsis

Bacterial sepsis

• Neutrophil leucocytosis: increased numbers of neutrophils.

• Immature granulocytes (= left-shift): occasional promyelocytes, myelocytes.

• Toxic granulation: coarse neutrophil granulation.

• Döhle bodies (these are white cells containing large RNA inclusions that are seen in, e.g., sepsis, malignancy, pregnancy).

Uncontrolled sepsis might be accompanied by:

Anaemia is common in bacterial sepsis and is usually related to the acute-phase response. Occasionally, haemolysis and red cell fragmentation accompany DIC, and severe haemolysis might complicate Clostridium welchii septicaemia with spherocytosis on the blood film.

Malaria (see also case on p. 14)

• Ask for the species of Plasmodium

• If P. falciparum, ensure you are given the parasite count. This indicates the severity of infection:

Some features of severe falciparum malaria

Remember

Treatment for severe malaria due to P. falciparum is a MEDICAL EMERGENCY. Give:

• Artesunate 2.4 mg/kg single bolus and then at 12 h and 24 h and then daily until oral medication can be tolerated.

• Quinine dihydrochloride 20 mg/kg IV over 4 h, then 10 mg/kg if artesunate unavailable.

See National Formulary for details; see p. 15 for other treatment.

Viral infections

Specific effects

• Glandular fever is produced by Epstein–Barr virus infection (see p. 18). Similar features are seen in cytomegalovirus but also in toxoplasmosis. The reactive lymphocytosis must be distinguished from a malignant lymphoid proliferation.

• Erythrovirus B19 causes Fifth’s disease and specifically infects erythroid progenitor cells, resulting in transient erythroid hypoplasia and failure of red cell production. This is of no consequence in otherwise healthy individuals but, in those with chronic haemolytic anaemia, it causes a sudden fall in the haemoglobin concentration, with absent reticulocytes. Urgent blood transfusion can be life saving.

• HIV infection results in anaemia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia in most patients. The severity of the cytopenia is related to the stage of the disease and is reflected by ineffective haemopoiesis with dysplastic changes in bone marrow precursor cells. It can be exacerbated by intercurrent infection and therapy.