CHAPTER 10 HAEMATOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

ANAEMIA IN THE CRITICALLY ILL

Anaemia is common in critically ill patients and often necessitates repeated blood transfusion. Anaemia may be the direct result of an underlying disease process, but more commonly is multifactorial. Common factors that may contribute to anaemia are listed in Box 10.1.

INDICATIONS FOR BLOOD TRANSFUSION

Oxygen carriage and delivery. The oxygen content of blood is given by Hb × SaO2 × 1.34. Raising haemoglobin is an effective way of improving oxygen content and delivery. (See Oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption, p. 68.)

Oxygen carriage and delivery. The oxygen content of blood is given by Hb × SaO2 × 1.34. Raising haemoglobin is an effective way of improving oxygen content and delivery. (See Oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption, p. 68.) Myocardial function. Myocardial ischaemia and diastolic dysfunction may occur in the stressed heart when the haematocrit falls below 0.18. In the presence of coronary artery disease, the threshold is 0.24 or higher.

Myocardial function. Myocardial ischaemia and diastolic dysfunction may occur in the stressed heart when the haematocrit falls below 0.18. In the presence of coronary artery disease, the threshold is 0.24 or higher. Rheology. In vitro and probably in vivo, blood viscosity is reduced as haematocrit falls below 0.24 and rises above 0.3. This may have implications for perfusion of the microcirculation, particularly in critical illness and following vascular surgery. Recent evidence suggests that both very low and very high haematocrits are associated with impaired tissue perfusion. Haematocrit can be estimated from Hb (g / dL) × 3/100.

Rheology. In vitro and probably in vivo, blood viscosity is reduced as haematocrit falls below 0.24 and rises above 0.3. This may have implications for perfusion of the microcirculation, particularly in critical illness and following vascular surgery. Recent evidence suggests that both very low and very high haematocrits are associated with impaired tissue perfusion. Haematocrit can be estimated from Hb (g / dL) × 3/100.BLOOD PRODUCTS IN THE UK

Recently, potential transmission of new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) has become a concern. It is likely that in the near future screening of donors for vCJD will become available. Currently in the UK all blood products have white cells removed (leucodepletion) as a precaution against vCJD transmission (white cell count < 5 × 106). Continuing concerns regarding the potential for carriage and transmission of vCJD by the UK blood donor pool has resulted in some plasma products being sourced from outside the UK, principally from the USA.

The following component blood products are available.

Red cells

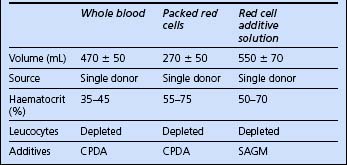

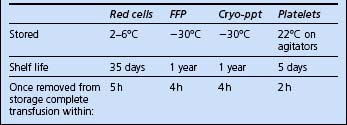

The blood products potentially available for red cell replacement are shown in Table 10.1.

Fresh frozen plasma

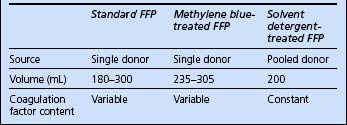

Recent concerns regarding virus transmission have resulted in treated plasma products becoming available. There are currently two: methylene blue treated and solvent detergent treated. The characteristics of available plasma products are compared in Table 10.2.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is provided as one to six single donations per pack, suspended in 10–20 mL plasma. It contains fibrinogen and factor VIII. It is used to correct coagulopathy where fibrinogen levels are depleted. Six units generally raise fibrinogen levels by approximately 1 g/L.

ADMINISTRATION OF BLOOD PRODUCTS

Requesting blood products

Check recipient identity

When possible, ask the patient to confirm his or her identity and that the details on the identification band are correct.

When possible, ask the patient to confirm his or her identity and that the details on the identification band are correct. Ensure that the patient’s name and identification number on the wristband match those on the intended blood product.

Ensure that the patient’s name and identification number on the wristband match those on the intended blood product.MAJOR HAEMORRHAGE

Ensure adequate vascular access: at least 2 × 14-gauge peripheral lines or single large-bore cannula such as 8.5-Fr introducer sheath. This need not necessarily be inserted into a central vein; a peripheral vein may well be easier to cannulate in an emergency, and just as adequate.

Ensure adequate vascular access: at least 2 × 14-gauge peripheral lines or single large-bore cannula such as 8.5-Fr introducer sheath. This need not necessarily be inserted into a central vein; a peripheral vein may well be easier to cannulate in an emergency, and just as adequate. Continue background or maintenance fluids to provide free water, glucose and electrolyte requirements.

Continue background or maintenance fluids to provide free water, glucose and electrolyte requirements. Commence initial volume replacement with a crystalloid or simple colloid such as modified gelatin (e.g. Gelofusine or Haemaccel).

Commence initial volume replacement with a crystalloid or simple colloid such as modified gelatin (e.g. Gelofusine or Haemaccel). After 5 units of blood, consider changing to whole blood if available and / or giving FFP to minimize the effects of dilutional coagulopathy.

After 5 units of blood, consider changing to whole blood if available and / or giving FFP to minimize the effects of dilutional coagulopathy. Ensure adequate treatment of coagulopathy. In particular, keep the ionized calcium above 0.85 mmol / L. Maintain normothermia with active warming of the patient if necessary.

Ensure adequate treatment of coagulopathy. In particular, keep the ionized calcium above 0.85 mmol / L. Maintain normothermia with active warming of the patient if necessary.RISKS AND COMPLICATIONS OF BLOOD TRANSFUSION

Complications of blood transfusion include fluid overload, hypothermia, hypocalcaemia, acidosis and dilutional coagulopathy. ARDS and multiple organ failure are also considered to be complications of massive transfusion. Bacterial contamination of blood occurs rarely and is usually fatal (platelet transfusion carries the greatest risk because of the need to store at room temperature).

Acute transfusion reactions are relatively uncommon. They include:

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI)

Antibodies in the transfused blood product cause activation of the recipient’s white cells, leading to an inflammatory response. The onset is typically within a few hours of transfusion and the clinical features are that of non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, which may lead on to the development of ARDS. If TRALI is suspected, the blood transfusion service should be advised so that donors can be screened for white cell antibodies. Treatment is supportive, as for any acute lung injury/ARDS. (See acute lung injury, p. 154.)

For more information on serious hazards of transfusion, see www.shotuk.org. SHOT (Serious Hazards Of Transfusion) is an independent professionally led organization that collects information relating to serious adverse transfusion reactions in the UK.

PATIENTS WHO REFUSE TRANSFUSION

Blood (red cells, whole blood), FFP, platelets may not be given to Jehovah’s Witnesses under any circumstances.

Blood (red cells, whole blood), FFP, platelets may not be given to Jehovah’s Witnesses under any circumstances. Factor concentrates: concentrates of specific factors (for example, factor XI, IX and VII) are generally accepted. Seek the advice of your hospital liaison committee.

Factor concentrates: concentrates of specific factors (for example, factor XI, IX and VII) are generally accepted. Seek the advice of your hospital liaison committee. Extracorporeal circuits. The majority of Jehovah’s Witnesses accept blood that has been passed through an extracorporeal circuit. This allows for cardiac surgery (cardiopulmonary bypass) and for renal dialysis. Intraoperative cell salvage is generally acceptable provided the blood is reinfused immediately, at the time of surgery, and not several hours later on the ICU.

Extracorporeal circuits. The majority of Jehovah’s Witnesses accept blood that has been passed through an extracorporeal circuit. This allows for cardiac surgery (cardiopulmonary bypass) and for renal dialysis. Intraoperative cell salvage is generally acceptable provided the blood is reinfused immediately, at the time of surgery, and not several hours later on the ICU. An individual contract / management plan may be prepared before treatment to clarify treatment options, when the patient is well enough to do this.

An individual contract / management plan may be prepared before treatment to clarify treatment options, when the patient is well enough to do this.Management

Patients with an anticipated major haemorrhage should receive supplementation of iron and other haematinics preoperatively.

Patients with an anticipated major haemorrhage should receive supplementation of iron and other haematinics preoperatively. Erythropoietin (EPO) may be prescribed to stimulate red cell production. Side-effects are uncommon, but include hypertension, headache and stroke. Not all patients respond.

Erythropoietin (EPO) may be prescribed to stimulate red cell production. Side-effects are uncommon, but include hypertension, headache and stroke. Not all patients respond.NORMAL HAEMOSTATIC MECHANISMS

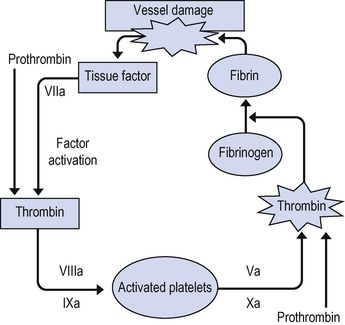

Factor VII and platelets adhere to exposed tissue factor (TF) in the vessel wall and release a number of mediators, including ADP. More platelets are attracted, which rapidly form a temporary haemostatic platelet plug.

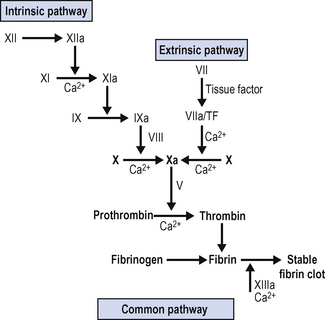

Factor VII and platelets adhere to exposed tissue factor (TF) in the vessel wall and release a number of mediators, including ADP. More platelets are attracted, which rapidly form a temporary haemostatic platelet plug. The coagulation cascade is triggered, which results in the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Cross-linking of fibrin molecules results in conversion of the primary platelet plug to an organized clot.

The coagulation cascade is triggered, which results in the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Cross-linking of fibrin molecules results in conversion of the primary platelet plug to an organized clot.The classical coagulation cascade is shown in Fig. 10.1. This represents the situation as present in vitro. While it is useful for understanding the serine protease cascade, and for working out in the laboratory the nature of coagulation disorders it does not represent the situation in vivo.

Factor VII forms a complex with tissue factor (TF) on the surface of cells at the site of injury, including platelets. This complex then initiates the coagulation cascade by activating factors X and IX, generating the so-called ‘thrombin burst’ and accelerating clot formation. This is shown in Fig. 10.2.

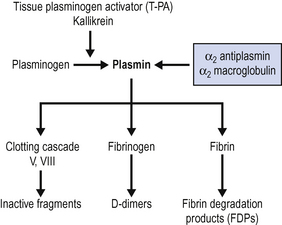

There are also mechanisms within the body to prevent clot formation in healthy vessels and to dissolve established clots. These fibrinolytic pathways are shown in Fig. 10.3.

Under normal circumstances, therefore, there is a constant balance maintained between procoagulant mechanisms and anticoagulant mechanisms. If this balance becomes disturbed, bleeding or thrombosis may result.

COAGULOPATHY

Causes

Coagulopathy may result from failure of clot formation, failure of clot stabilization or excessive activation of fibrinolysis. Often more than one process is involved, and the early involvement of a haematologist is advisable. Typical causes of coagulopathy are shown in Box 10.2.

Box 10.2 Typical causes of coagulopathy

| Congenital | Acquired |

|---|---|

| Haemophilia A (factor VIII) | Acquired / functional factor deficiency |

| Haemophilia B (factor IX) | Dilutional coagulopathy |

| Von Willebrand’s disease | Thrombocytopenia |

| Other factor deficiencies | Sepsis |

| Hypothermia | |

| Hepatic dysfunction | |

| Vitamin K deficiency / malabsorption | |

| Renal failure | |

| Drugs |

Sepsis may produce bone marrow suppression (thrombocytopenia) and triggers inflammatory cascades, which activate both coagulation and fibrinolysis.

Sepsis may produce bone marrow suppression (thrombocytopenia) and triggers inflammatory cascades, which activate both coagulation and fibrinolysis. Reduced gastrointestinal absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) leads to reduced manufacture of vitamin K-dependent factors (II, VII, IX, X, protein C).

Reduced gastrointestinal absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) leads to reduced manufacture of vitamin K-dependent factors (II, VII, IX, X, protein C). Reduced hepatic reticuloendothelial function permits increased circulating levels of endogenous heparinoids (potentiating antithrombin III and inhibiting factors V, X).

Reduced hepatic reticuloendothelial function permits increased circulating levels of endogenous heparinoids (potentiating antithrombin III and inhibiting factors V, X). Citrate anticoagulants may persist in the circulation for some time, chelating calcium and potentially reducing cardiac contractility. Additionally, some synthetic colloids may impair platelet function (dextrans, hetastarch in particular).

Citrate anticoagulants may persist in the circulation for some time, chelating calcium and potentially reducing cardiac contractility. Additionally, some synthetic colloids may impair platelet function (dextrans, hetastarch in particular).Investigations

Basic investigations include platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), thrombin time (TT), fibrinogen, and fibrinogen breakdown products (FDPs / D dimers). If a specific factor deficiency is considered likely, then individual factor assay may be appropriate. Seek haematological advice. Normal ranges are shown in Table 10.4.

| Normal range | Significance | |

|---|---|---|

| Platelets | 150–450 × 109/L | See thrombocytopenia below |

| PT | 12–14 s (INR = PT/control; normal INR = 1) | Extrinsic and common pathway Marker of hepatic dysfunction / vitamin K deficiency Used to monitor warfarin therapy |

| APTT | 30–40 s | Intrinsic and common pathway Used to monitor heparin therapy |

| TT | 10–12 s | Tests conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin Prolonged by heparin/FDPs/D dimers |

| Fibrinogen | >2 g/L | Reduced in dilutional coagulopathy, liver failure, fibrinolysis (DIC) |

| D dimers | <0.2 g/L | Increased in presence of fibrinolysis (DIC) |

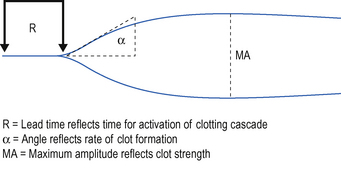

Thromboelastography (TEG)

While the in-vitro tests listed above can be useful diagnostically to determine the likely cause of a coagulopathy, they test individual aspects of the coagulation process rather than reflect the overall process of clot formation. The thromboelastograph can be used to provide a dynamic test of coagulation and fibrinolysis. This can be used to help identify the need for FFP, cryoprecipitate, platelets or antifibrinolytic therapy. An increasing number of hospitals have access to TEG devices in theatre and some critical care units. If available, you should familiarize yourself with the device and interpretation of the information that it gives you before you have to use it in an emergency situation. There is now a body of evidence to suggest that the management of coagulopathy based on interpretation thromboelastogram and related technologies not only helps in the management of haemostasis, but also reduces the quantities of clotting products required. A typical TEG trace is shown in Fig. 10.4.

Management of coagulopathy

Ensure that the patient is adequately resuscitated. Oxygen, i.v. access and adequate volume or blood replacement. Correct hypothermia.

Ensure that the patient is adequately resuscitated. Oxygen, i.v. access and adequate volume or blood replacement. Correct hypothermia. The commonest cause of bleeding in the postoperative patient is failure of surgical haemostasis. Surgical causes of bleeding must be excluded. Seek surgical advice.

The commonest cause of bleeding in the postoperative patient is failure of surgical haemostasis. Surgical causes of bleeding must be excluded. Seek surgical advice. Other underlying causes of bleeding and coagulopathy should be addressed. Do not forget inherited causes, e.g. the haemophilias, although these are rare.

Other underlying causes of bleeding and coagulopathy should be addressed. Do not forget inherited causes, e.g. the haemophilias, although these are rare. Perform basic investigations of haemostasis, as above. The diagnosis should be clear from a combination of history, examination and the results of these tests.

Perform basic investigations of haemostasis, as above. The diagnosis should be clear from a combination of history, examination and the results of these tests. If the APTT is prolonged, suspect heparinoids or other inhibitors. The laboratory may be able to repeat the APTT in the presence of a heparinase to help distinguish this.

If the APTT is prolonged, suspect heparinoids or other inhibitors. The laboratory may be able to repeat the APTT in the presence of a heparinase to help distinguish this. If heparin is present, but you do not know how much has been given, give protamine 50 mg then repeat the APTT. If you know the dose of heparin given, then protamine 1 mg per 100 units of heparin given should provide adequate reversal.

If heparin is present, but you do not know how much has been given, give protamine 50 mg then repeat the APTT. If you know the dose of heparin given, then protamine 1 mg per 100 units of heparin given should provide adequate reversal. If the PT and APTT are prolonged in the absence of exogenous anticoagulants give FFP, which should be administered in 2–4 unit aliquots until PT falls below 20 s. Additionally, if fibrinogen depletion is marked, consider cryoprecipitate 6 units initially.

If the PT and APTT are prolonged in the absence of exogenous anticoagulants give FFP, which should be administered in 2–4 unit aliquots until PT falls below 20 s. Additionally, if fibrinogen depletion is marked, consider cryoprecipitate 6 units initially. If the platelet count is < 80 × 109/L, give 4 units of platelets, although more may be required if the count is lower or where the response to transfusion is limited, for example in DIC. In renal failure, platelet function may be abnormal even if platelet numbers are adequate. Desmopressin (DDAVP) 20 μg as a one-off bolus releases peripheral stores of factor VIII:Rag. This increases platelet ‘stickiness’ and thereby improves function.

If the platelet count is < 80 × 109/L, give 4 units of platelets, although more may be required if the count is lower or where the response to transfusion is limited, for example in DIC. In renal failure, platelet function may be abnormal even if platelet numbers are adequate. Desmopressin (DDAVP) 20 μg as a one-off bolus releases peripheral stores of factor VIII:Rag. This increases platelet ‘stickiness’ and thereby improves function.Activated factor VII (VIIa)

There has been a great deal of interest recently in the role of activated factor VII in the management of coagulopathy and uncontrolled bleeding. Activated factor VII binds to exposed tissue factor on damaged endothelial surfaces and activates the coagulation process, leading to localized fibrin production and clot formation. There is increasing evidence that VIIa is effective in reducing bleeding when other measures have failed. (See Normal haemostatic mechanisms, p. 255.)

THROMBOCYTOPENIA

Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in critically ill patients. Common causes are shown in Box 10.3.

Box 10.3 Causes of thrombocytopenia

| Reduced production | Increased destruction / sequestration |

|---|---|

| Bone marrow failure Drugs, toxins Viral infections |

Infection Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Mechanical devices (balloon pump/CVVHD) Clot / mechanical destruction Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) Immune thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP) Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) Sequestration (e.g. splenomegaly) |

DISSEMINATED INTRAVASCULAR COAGULATION

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a complex process arising as a result of generalized activation of the inflammatory cascade. It involves activation of clotting within the microvasculature, with consequent tissue damage. There is a consumptive coagulopathy, where normal clotting fails to take place because of depletion of circulating factors. The process is generally accompanied by activated fibrinolysis, with clot instability. The breakdown products of fibrinogen (D-dimer) and fibrin (FDPs) are in themselves anticoagulant, thus adding an extra level of complexity.

PURPURIC DISORDERS

Purpura are small purple spots in the skin resulting from microvascular haemorrhage. Although these are not always pathological, e.g. ‘senile purpura’ is secondary to vessel fragility in old age, they should raise suspicion of underlying pathology. Typically, purpura are associated with thrombocytopenia (see above), but they are also seen in other conditions in which there is inflammation or damage to the microvasculature. Important causes are shown in Box 10.4.

THROMBOTIC DISORDERS

A number of factors predispose to thrombosis in ICU patients (Table 10.5).

| Vascular endothelial damage | Trauma / surgery Central venous catheters |

| Altered blood flow | Vascular disease Immobilization Shock states Central venous catheters Effects of vasoactive drugs |

| Altered platelet activity and coagulation state | Underlying disease processes Activation of inflammatory cascades Stress response to surgery, trauma, sepsis |

Some patients are at particular at risk of thrombosis. These include the pregnant, the obese and those with carcinomatosis, pelvic / hip injuries or surgery, myeloproliferative disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus anticoagulant) and conditions such as TTP–HUS (see TTP–HUS, p. 263).

Arterial thrombosis / embolization

Arterial thrombosis / embolization commonly follows vascular surgery in arteriopathies, but can also be seen following trauma or accompanying other prothrombotic conditions such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) (see p. 263). Peripheral small vessel occlusion (e.g. trash foot) is common after aortic surgery, but may also accompany other conditions such as bacterial endocarditis and mycotic aneurysm. This usually improves over time. Embolization of a peripheral (limb) artery results in a pale, weak, numb and pulseless limb with loss of Doppler signals. Central arterial thrombosis of the distal aorta also occurs rarely (saddle embolus).

Management of thrombosis

Systemic anticoagulation is usually required either with therapeuatic doses of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin, e.g. Enoxaprin 150 units / kg / day, or with unfractionated intravenous heparin, typically 5000 unit loading dose followed by an infusion of 18 units / kg / 24 h adjusted according to APTT.

Systemic anticoagulation is usually required either with therapeuatic doses of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin, e.g. Enoxaprin 150 units / kg / day, or with unfractionated intravenous heparin, typically 5000 unit loading dose followed by an infusion of 18 units / kg / 24 h adjusted according to APTT. In cases of thrombosis associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the newer drugs lepirudin and fondaparinux avoid exacerbating HIT and can be administered parenterally, but care is required in appropriate dosing as excessive anticoagulation can be problematic. Unlike heparin or warfarin, they cannot easily be reversed. Seek advice from a haematologist on drug selection, dosage and monitoring.

In cases of thrombosis associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, the newer drugs lepirudin and fondaparinux avoid exacerbating HIT and can be administered parenterally, but care is required in appropriate dosing as excessive anticoagulation can be problematic. Unlike heparin or warfarin, they cannot easily be reversed. Seek advice from a haematologist on drug selection, dosage and monitoring.THE IMMUNOCOMPROMISED PATIENT

All critically ill patients on the intensive care unit should be considered to have some degree of altered immune function (immunocompromise). The causes are multifactorial as shown in Box 10.5.

Box 10.5 Causes of altered immune function in critically ill patients

Impaired barrier defences (breaches in skin / impaired cough reflexes / impaired gut perfusion)

Some specific patient groups are particularly at risk of relative immunocompromise. These include those with alcoholic liver disease and those suffering from malignancy. Such immunocompromise may be difficult to diagnose, as bone marrow function and other measures of response to infection may be apparently normal.

Patients with significant immunocompromise are, however, increasingly common in the ICU. Immune deficiency may be inherited (e.g. severe combined immune deficiency, SCID) or acquired. Most commonly, it is seen in patients with depressed bone marrow function, either as a result of an underlying disease process or as a result of treatment (e.g. following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive treatment following transplantation). Typical causes of significant immunocompromise are shown in Box 10.6.

Management

The principles of management are largely the same as for the immunocompetent patient. Resuscitation and stabilization are the initial priorities.

Long term venous catheters are a common site of catheter-related sepsis. The infection may be obvious externally (swab entry site), or there may be no external signs of infection despite infected thrombophlebitis and / or catheter associated clot. Consider removal.

Long term venous catheters are a common site of catheter-related sepsis. The infection may be obvious externally (swab entry site), or there may be no external signs of infection despite infected thrombophlebitis and / or catheter associated clot. Consider removal.AIDS

Patients newly presenting with a disease characteristic of an immunosuppressed state, and who are subsequently diagnosed as HIV positive during the course of critical care admission, would not normally be commenced on antiretroviral therapy until after discharge from the intensive care unit, or recovery from the acute infective process. This is because acute institution of antiretroviral agents is unlikely significantly to affect the prognosis during the acute illness.

In some hospitals, a form accompanies blood products, identifying the units issued; this is intended as a record to be placed in the patient’s notes. These forms are not intended to be used as part of the checking procedure, and do not help to ensure that the correct unit of blood is given to the correct patient. The only acceptable checking process is to confirm that the patient details on the product label and those on the patient’s wrist band are the same.

In some hospitals, a form accompanies blood products, identifying the units issued; this is intended as a record to be placed in the patient’s notes. These forms are not intended to be used as part of the checking procedure, and do not help to ensure that the correct unit of blood is given to the correct patient. The only acceptable checking process is to confirm that the patient details on the product label and those on the patient’s wrist band are the same.

In some cases, thrombocytopenia is associated with increased microvascular thrombotic processes. Under these circumstances, giving platelets may increase the risk of clinically significant thrombosis. Do not give platelets unless there is active bleeding, or the platelet count is less than 20 × 109/L and the risk of thrombosis has been excluded (see below).

In some cases, thrombocytopenia is associated with increased microvascular thrombotic processes. Under these circumstances, giving platelets may increase the risk of clinically significant thrombosis. Do not give platelets unless there is active bleeding, or the platelet count is less than 20 × 109/L and the risk of thrombosis has been excluded (see below).