Chapter 8 HAEMATEMESIS AND MELAENA

INTRODUCTION

Acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is one of the most common emergency conditions and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Haematemesis is the vomiting of fresh blood. Haematemesis indicates that bleeding originates from a site proximal to the ligament of Treitz. A history of fresh haematemesis usually implies a significant bleed. Vomiting altered blood that appears like coffee grounds arises from the breakdown of haemoglobin by gastric acid, and often indicates that active bleeding may have ceased. Melaena is the passage of black, tarry stool. It occurs when haemoglobin is converted to haematin by bacterial degradation. Ingestion of as little as 200 mL of blood can produce melaenic stool. Although melaena generally connotes bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz, bleeding from the small intestine or proximal colon may also cause melaena, especially when colonic transit is slow. Haematochezia is the passage of pure red blood or blood admixed with stool. It usually occurs as a result of bleeding in the lower GI tract. It can also be present in massive upper GI bleeding (in 10%–15% of cases).

AETIOLOGY

The most common cause of upper GI bleeding is peptic ulcer. This is followed by mucosal erosions, Mallory-Weiss tear, oesophagitis and oesophageal/gastric varices. In the lower GI tract, the most common causes of bleeding are diverticular disease, vascular malformation, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal neoplasia (Table 8.1). In general, bleeding from the upper GI tract is more common than lower GI tract bleeding.

TABLE 8.1 Causes of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding

| Upper GI bleeding | Lower GI bleeding | |

|---|---|---|

| Common |

High-risk patients

Significant GI bleeding is indicated by syncope, haematemesis, tachycardia (pulse rate >100 beats per minute), systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg (13.3 kPa), postural hypotension and requiring more than 4 units of blood to be transfused within 12 hours to maintain blood pressure. Patients over 60 years of age with multiple underlying diseases (comorbidities) are at higher risk of mortality. Those admitted for comorbid medical problems (e.g. heart or respiratory failure, or a cerebrovascular bleed) who develop GI bleeding during hospitalisation also have a higher mortality risk.

INVESTIGATIONS

Endoscopy

Endoscopic examination offers three functions. It:

The following should be done during endoscopy.

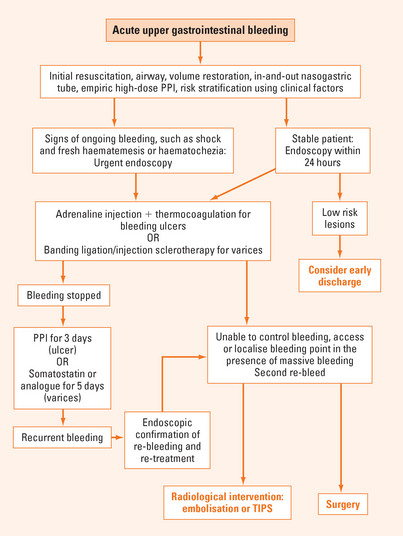

MANAGEMENT

Pharmacological therapy

Acid suppressing drugs

Acid suppressing drugs such as H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are effective drugs to promote ulcer healing, however H2-receptor antagonists do not control acute bleeding. As an acidic environment impairs platelet function and haemostasis, reducing the secretion of gastric acid should reduce bleeding. Potent acid suppression using intravenous PPIs (e.g. esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole or rabeprazole) reduces recurrent bleeding after endoscopic therapy. PPIs should be recommended as an adjuvant to endoscopic therapy in patients with peptic ulcers with a high risk of bleeding.

Radiological therapy

Angiography is an important tool for diagnosing GI bleeding when endoscopy fails to identify the source. The advantages of angiography include accurate localisation of rapidly bleeding lesions and the potential to achieve immediate control with several treatment modalities:

BLEEDING OF OBSCURE ORIGIN

The source of bleeding remains unidentified after gastroscopy and colonoscopy in about 5% of patients. The most common causes include angiodysplasia, small intestine neoplasms, Meckel’s diverticulum, ectopic varices and conditions causing haemobilia. Bleeding as a result of these conditions is often difficult to manage. In the past, red blood cell scintigraphy and angiography were the two commonly used diagnostic tools, but the yields were very low. With the advent of capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy, the diagnosis and treatment success of these conditions is much improved. While capsule endoscopy is much more comfortable and, hence, better tolerated by patients, double balloon enteroscopy offers an opportunity to control the bleeding when a source is found.

Chung SS, Lau JY, Sung JJ, et al. Randomized comparison between adrenaline injection alone and adrenaline injection plus heat probe treatment for actively bleeding ulcers. Brit Med J. 1997;314:1307-1311.

Gross M, Schiemann U, Muhlhofer A, et al. Meta-analysis: efficacy of therapeutic regimens in ongoing variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2001;33:737-746.

Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Proton pump inhibitors for acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2006. CD002094

Rollhauser C, Fleischer DE. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2004;36:52-58.