Chapter 30 Gynecologic Procedures

Gynecologic procedures are becoming less invasive and safer, and advances in surgical technique are resulting in more effective and efficient reproductive healthcare for women. Smaller and more flexible instrumentation for endoscopic procedures and the development of robotic techniques are examples of these recent advances.

Appropriateness of Gynecologic Procedures

Appropriateness of Gynecologic Procedures

At least 80% of gynecologic surgical procedures are considered to be elective; that is, there are other alternative treatments to be considered. The appropriateness of performing these procedures should be evaluated by physician and patient on an individual basis (Box 30-1). The trend toward minimal invasiveness in gynecologic surgery should not lead to minimal or questionable indications.

BOX 30-1 The PREPARED Checklist∗

∗ PREPARED is a useful mnemonic checklist to assess preoperatively the appropriateness of a health-care procedure, including elective gynecologic surgery. An analysis of each gynecologic or other health-care procedure can be carried out and the patient completely and efficiently counseled using this format.

Credentialing, Privileging,and Ongoing Training

Credentialing, Privileging,and Ongoing Training

After a surgeon’s credentials (diplomas, training certificates, and licenses) have been properly verified, a useful classification for the purpose of privileging stratifies procedures into the following levels: level 1, procedures not requiring additional training after residency (e.g., dilatation and curettage [D&C], cervical conization, adnexal excision, and abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy); level 2, procedures requiring additional training (e.g., laparoscopic myomectomy); and level 3, procedures requiring advanced training and special skills generally acquired during subspecialty training (e.g., radical hysterectomy, tubal anastomosis, or oocyte harvesting).

As new procedures are incorporated into basic residency training, they can be reclassified.

Informed Consent and General Risks Associated with Procedures

Informed Consent and General Risks Associated with Procedures

The patient should be thoroughly counseled about surgical risks as part of the process of informed consent (see Chapter 1). In general, risks fall into three categories: risks of anesthesia, intraoperative risks, and postoperative complications. Risks of anesthesia depend on the type of anesthesia used (awake sedation, regional anesthesia, or inhalation agents). Regional anesthesia carries the risk for infection, postprocedure spinal headache, and failure, in which case an inhalation agent must be added to the regional anesthetic. Inhalation agents may be associated with the risk for aspiration pneumonia, allergic reaction to the agent, and damage to teeth or airways if intubation is necessary. Stroke, myocardial infarction, and death can result. The intraoperative risks include excessive bleeding and unintended damage to organs or tissue. Postoperative risks include infection, persistent bleeding, and thrombosis, all of which can lead to significant morbidity or even mortality. The specific risks of each procedure are given later.

Endometrial Sampling Procedures

Endometrial Sampling Procedures

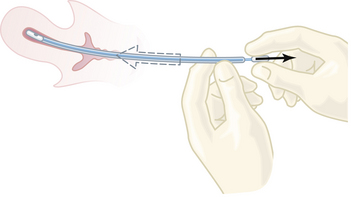

One of the most common minor gynecologic surgical procedures is D&C: dilation of the cervix and curettage of the endometrium. Recent advances in office-based instrumentation for diagnosis (hysteroscopy, endometrial sampling [Figure 30-1], and ultrasonic evaluation of endometrial thickness) have resulted in an appropriate decrease in the use of D&C. However, if cancer of the cervix or endometrium is suspected, a thorough fractional curettage may be the best procedure to confirm its presence.

COMPLICATIONS

The most common surgical complications of D&C are hemorrhage, infection, perforation of the uterus, and laceration of the cervix. Perforation of the uterus, even in experienced hands, is a not uncommon complication and occurs particularly with a retroverted uterus, during pregnancy, or in postmenopausal patients with endometrial cancer. As long as no bowel or large blood vessels are injured, careful observation and antibiotics may be all the therapy that is required.

Cervical Procedures

Cervical Procedures

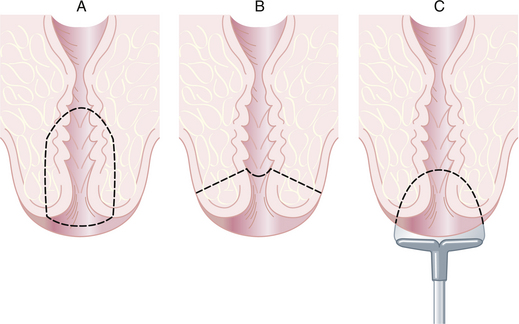

Conization of the cervix is a procedure in which a cone-shaped portion of the cervix is removed for diagnostic or occasionally therapeutic purposes. The section of the tissue surrounding the external os represents the base of the removed specimen. The apex is either close to the internal os (Figure 30-2A) or close to the external os (Figure 30-2B). Conization may also be performed in an office setting using loop electrosurgical excision (Figure 30-2C) or large loop excision of the transformation zone of the cervix. Loop excision should not be performed before identification of a cervical intraepithelial lesion that requires treatment by colposcopically directed punch biopsy.

Pelvic Endoscopy

Pelvic Endoscopy

Gynecologic endoscopy (laparoscopy and hysteroscopy) is widely used for the diagnosis and treatment of reproductive organ disease and dysfunction. Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy have largely moved from the hospital operating room to the freestanding surgical outpatient unit, and with smaller instruments (needle-scopes) and more refined fiberoptic technology, even into the office setting. Because of the expenseinvolved, the value of these techniques must be considered in terms of outcome, particularly the long-term health and functional status of the patient.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy

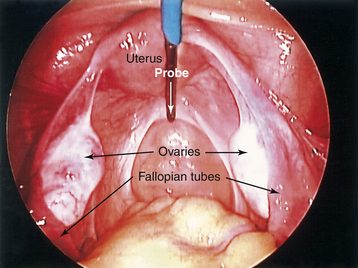

The laparoscope is an instrument for viewing the peritoneal cavity. Both pelvic and upper abdominal structures can be inspected. The attachment of a video camera on the lens of the laparoscope allows more than one surgeon to view the operative site on a video screen and assist during procedures (Figure 30-3). Multiple puncture sites through the skin and into the abdominal cavity provide for the insertion of small rigid or flexible instruments directed toward the pelvis. Procedures that were once performed by laparotomy are now routinely carried out less invasively.

INDICATIONS

The following are indications for laparoscopy:

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy

HYSTEROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTATION

The hysteroscope (Figure 30-4) is a telescope consisting of light bundles and a sheath through which the telescope is inserted. For pure diagnostic use, the telescope is inserted alone, whereas for operative capabilities, it is inserted in conjunction with other instruments.

OFFICE-BASED VS HOSPITAL-BASED HYSTEROSCOPY

Telescopes have become progressively narrower and can now be safely inserted into the cervical canal with minimal pain. Several manufacturers have small office-based telescopes that use physiologic low-viscosity distention fluids such as saline or Ringer’s lactate. These allow the performance of hysteroscopy with little more than a paracervical block in patients who are bleeding, and they do not cause the shoulder pain and uterine spasm that often accompany use of carbon dioxide as a distention medium. At present, a significant number of hysteroscopies are performed as office procedures.

OPERATIVE PROCEDURES

Endometrial Ablation

After a preoperative drug regimen to suppress the endometrial thickness (danazol or leuprolide), hysteroscopic laser surgery can be performed on an outpatient basis under general or regional anesthesia in about 1 hour. A hysteroscope is introduced into the uterus and a fiberoptic delivery system is passed through the operating channel. Resectoscopic endometrial ablation has become a more popular technique than laser ablation, and it appears to be at least as effective; its advantages are a significantly shorter operating time and much less expensive equipment.

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy

Table 30-1 provides a useful list of indications for abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy.

| ACUTE CONDITION | |

| A-1∗ | Pregnancy catastrophe (e.g., severe hemorrhage) |

| A-2 | Severe infection (e.g., ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess) |

| A-3∗ | Operative complication (e.g., uterine perforation) |

| BENIGN DISEASE | |

| B-1 | Leiomyomas |

| Symptomatic (e.g., bleeding, pressure) | |

| Asymptomatic (≥12 wk size, confuses adnexal evaluation) | |

| B-2 | Endometriosis (distinct endometriosis, unresponsive to hormonal suppression or conservative surgery) |

| B-3 | Adenomyosis (with symptomatic menometrorrhagia unresponsive to treatment) |

| B-4 | Chronic infection (e.g., recurrent pelvic inflammatory disease) |

| B-5 | Adnexal mass (e.g., ovarian neoplasm) |

| B-6 | Other (operator defined, criteria specified) |

| CANCER OR SIGNIFICANT PREMALIGNANT DISEASE | |

| C-1 | Invasive disease of reproductive organs |

| C-2 | Significant preinvasive disease of the uterus (CIN-3 or adenomatous hyperplasia of the endometrium with cellular atypia) |

| C-3 | Cancer of adjacent or distant organ (gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or breast cancer) |

| DISCOMFORT (NO CONFIRMING TISSUE PATHOLOGY EXPECTED) | |

| D-1∗ | Chronic pelvic pain (negative laparoscopy and nonsurgical treatment attempted) |

| D-2∗ | Pelvic relaxation (symptomatic) |

| D-3∗ | Recurrent uterine bleeding (unresponsive to hormone regulation, curettage, or endometrial ablation—normal-sized uterus) |

| D-4∗ | Other (operator defined, criteria specified) |

| EXTENUATING CIRCUMSTANCES (NOT SPECIFICALLY INDICATED BUT POSSIBLY JUSTIFIED—REQUIRES PREOPERATIVE PEER REVIEW) | |

| E-1∗ | Sterilization (extenuating circumstances) |

| E-2∗ | Cancer prophylaxis (e.g., recurrent CIN after cone biopsy or persistent adenomatous hyperplasia of the endometrium without atypia) |

| E-3∗ | Other—listing extenuating circumstances |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

∗ Denotes indications for which tissue pathology is not expected to confirm the preoperative diagnosis.

Data from Gambone JC, Lench JB, Slesinski MJ, et al: Validation of hysterectomy indications and the quality assurance process. Obstet Gynecol 73:1045, 1989.

ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY

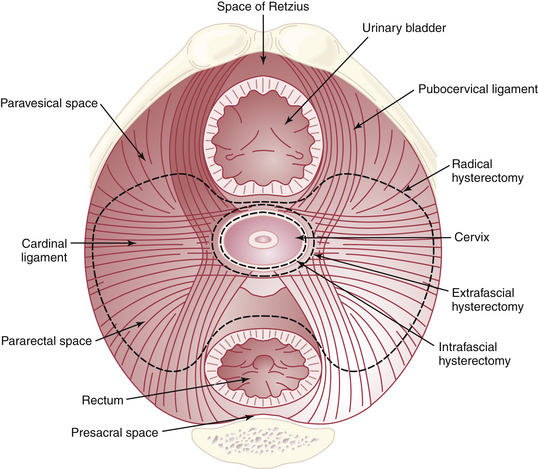

A total abdominal hysterectomy is the most commonly performed procedure for benign uterine disease and involves the “simple” excision of the uterine corpus and cervix. It may be performed intrafascially, in which case the surgeon stays safely within the endopelvic fascia that surrounds the cervix and upper vagina, or extrafascially, in which case the investing fascia of the cervix and upper vagina is removed with the specimen. A subtotal hysterectomy excises the uterine corpus, usually at the level of the internal cervical os. A radical hysterectomy involves the wide excision of the parametrial tissue laterally (Figure 30-5), along with the uterosacral ligaments posteriorly, after the rectum is dissected free and after each ureter is dissected out of its tunnel beneath the uterine artery.

Technique

Abdominal hysterectomy is carried out with the patient in the supine position, usually under general anesthesia. First, a thorough pelvic and abdominal examination under anesthesia is carried out and recorded. The choice of incision depends on the indication for the procedure. A vertical incision is advisable in patients who have had several prior abdominal operations, are extremely obese, or in whom extensive adhesions or endometriosis is anticipated. In patients with restricted benign disease, incisions along the lines of Langer (transverse in the lower abdomen) achieve a better cosmetic result. The various lower abdominal incisions and their anatomy are discussed in Chapter 3 and depicted in Figure 3-12.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY

Technique

The principles of the operation are similar to those of abdominal hysterectomy except that ligation of the ligaments and vessels proceeds in the reverse order. The patient is placed in the dorsolithotomy position after induction of anesthesia. The bladder is emptied, and a thorough pelvic examination is performed. A weighted vaginal retractor is placed in the vagina, a tenaculum is placed on the cervix, and the uterus is drawn down toward the vaginal introitus and tested for descent and mobility. A transverse incision is made through the vaginal epithelium between the uterosacral ligaments at the posterior junction of the cervix and vagina. The peritoneum of the cul-de-sac is bluntly mobilized and sharply entered. Adhesions of the cul-de-sac and posterior uterine wall are excluded by finger exploration. The uterosacral ligaments are clamped, cut, and ligated, allowing additional descent of the uterus.

COMPLICATIONS OF HYSTERECTOMY

Injury to the ureter is the most serious complication of hysterectomy and usually occurs during the abdominal procedure, particularly during a difficult dissection for PID, endometriosis, or pelvic cancer. Ureteral injury can also occur during a vaginal hysterectomy. If not detected intraoperatively, fever and flank pain can develop postoperatively, and a ureterovaginal fistula or urinoma may become apparent 5 to 21 days after surgery. If noted intraoperatively, a ureteral injury can be repaired by implanting the proximal cut end of the ureter into the bladder or by anastomosing the proximal and distal ends of the transected ureter over a ureteric stent.

Robotic Surgery in Gynecology

Robotic Surgery in Gynecology

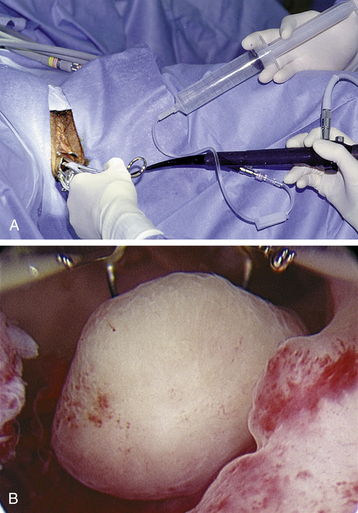

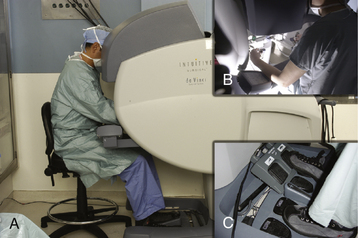

The role of computer-assisted or robotic surgery in gynecology is evolving. Prospective studies are needed to compare the efficacy of this technology to conventional methods. In 2005, the da Vinci surgical system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, Calif) received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval (Figure 30-6). As this new technology is introduced to improve surgical performance, its limitations (such as lack of tactile feedback and increased cost) will need to be addressed. Robotic-assisted instrumentation is being used for hysterectomy, pelvic reconstructive surgery, and gynecologic oncology.

Abstracts of the Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, 36th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, Washington, DC. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 14(6 Suppl):S1-S154, 2007.

Advincula A.P., Song A. The role of robotic surgery in gynecology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:331-336.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Technology Assessment in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Hysteroscopy. Washington, DC: ACOG, 2005. pp 350–353

Hart R., Karthigasu B., Drishnan A. The benefits of virtual reality simulator training for laparoscopic training. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:297-302.

Reich H. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Indications, tech-niques and outcomes. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:337-344.