chapter 52 Gynaecology

ANATOMY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE UTERINE CERVIX

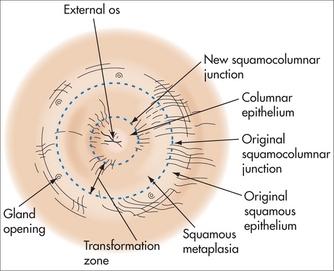

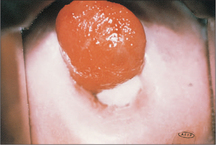

The ectocervix is covered by pink squamous epithelium, which changes suddenly to the red columnar (glandular) epithelium of the endocervix at the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) (Fig 52.2). The columnar epithelium is shorter in height than squamous epithelium and appears red because the thin cell layer allows the underlying blood vessels to be easily seen. Columnar epithelium invaginations into the cervical stroma form endocervical glands.

Newly formed immature metaplastic epithelium may develop into either:

CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Since 1990, a simplified two-grade histological system using the term ‘squamous intraepithelial lesion’ (SIL), known as The Bethesda System, has been used.

MANAGEMENT OF ABNORMAL SMEARS

Abnormal cytology results frequently cause significant fear and anxiety for the woman, including:

Colposcopy

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS INFECTION

Oncogenic HPV infection is also associated with:

PREVENTION OF CERVICAL DYSPLASIA

TREATMENT OF CONFIRMED CERVICAL DYSPLASIA

ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

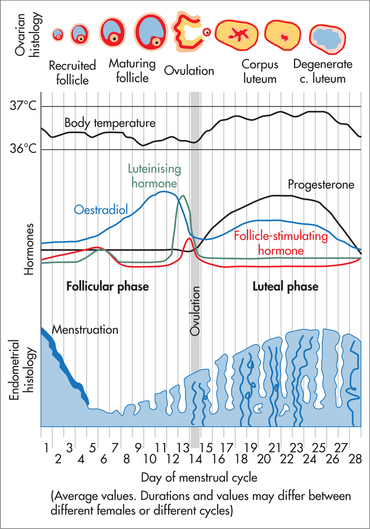

The process of normal regular menstruation requires:

AETIOLOGY

Herbal substances associated with bleeding include ginseng, ginkgo and soy supplements.

HISTORY

EXAMINATION

Examination may be normal but should include:

INVESTIGATIONS

MANAGEMENT

Teenagers presenting acutely with prolonged heavy bleeding (anovulatory cycles):

Ovulatory, regular, heavy periods:

Perimenopausal women with frequent irregular periods and variable flow:

DYSMENORRHOEA

Dysmenorrhoea can be considered ‘normal’ if:

MANAGEMENT

Management options for ‘normal period pain’ include:

Pharmacological

Dysmenorrhoea that does not resolve with the OCP or anti-inflammatories requires investigation. Common causes include endometriosis and adenomyosis. Any woman old enough to have periods is old enough to have endometriosis. While pregnancy frequently improves day 1–2 period pain in normal nulliparae, it seldom improves dysmenorrhoea in women with endometriosis and is inappropriate to recommend outside a suitable social setting.

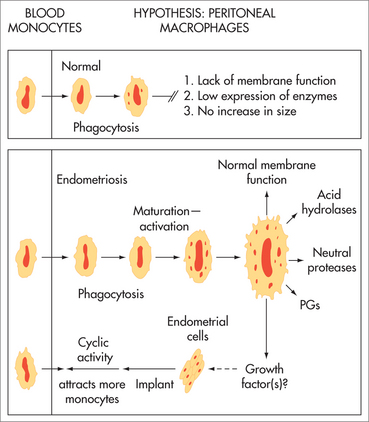

ENDOMETRIOSIS

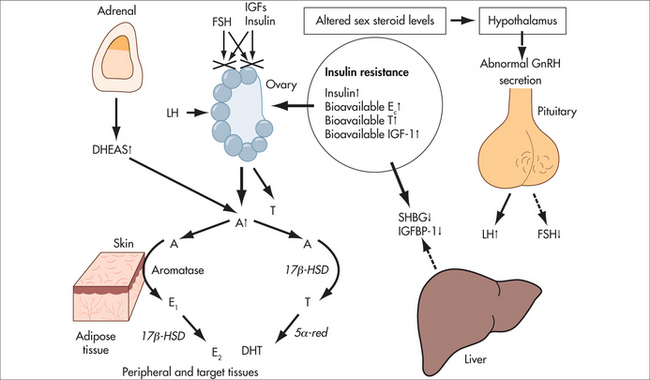

AETIOLOGY

The aetiology of endometriosis is unknown. It is increasing in prevalence. A tendency to develop endometriosis is inherited as a complex genetic trait influenced by environmental factors.13 Established lesions include inflammatory cells, fibrosis, neovascularisation and aberrant innervation. It has been associated with environmental toxins including organochlorines (polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxin-like compounds).14

SYMPTOMS

In the past, endometriosis was considered an uncommon condition of women in their thirties and forties. We now know it to be a common condition (5–10%) of women in their teens and twenties.

While some women are asymptomatic, common symptoms include:

Dysmenorrhoea is usually a combination of pain from the endometriosis and pain from the uterus. The endometrium of women with endometriosis has nerve fibres (pain receptors) not present in women without endometriosis.16 Optimal outcome requires management of both endometriotic lesions and the uterine component of pain.

HISTORY

DIAGNOSIS

INVESTIGATIONS

Ultrasound

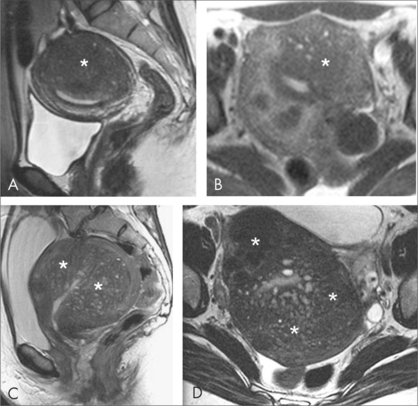

MRI

Rarely required. May be used to investigate rectosigmoid disease or diagnose coexistent adenomyosis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Explanation and support

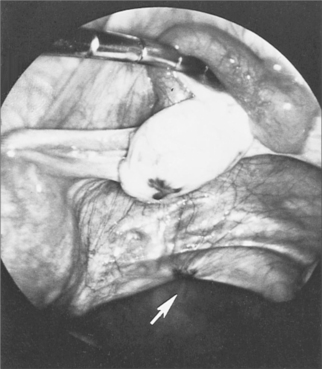

Laparoscopy

Once the diagnosis has been made, options include:

Dietary and complementary therapies

Medical treatments

Consider treatment of coexistent causes of pelvic pain at the laparoscopic procedure. For example:

A full discussion of the management of endometriosis is available in textbooks on this topic.22

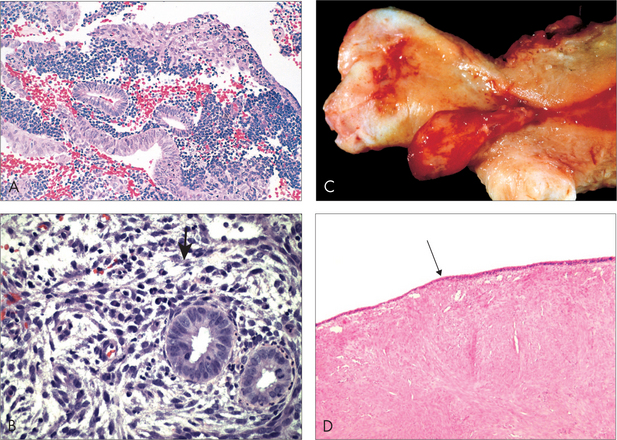

ADENOMYOSIS

SYMPTOMS

TREATMENT

If asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Treatment options include:

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

These symptoms may develop even when all her endometriosis has been removed and after hysterectomy. In women with pain on most days, a central chronic pain process is likely, and management usually includes neuropathic pain medications, cognitive behavioural lifestyle changes, and management of the local pelvic symptoms.24

MANAGEMENT

SPECIFIC PAIN SYMPTOMS AND THEIR MANAGEMENT

Urgency, frequency and nocturia

These are commonly due to interstitial cystitis (IC) or painful bladder syndrome (PBS). IC commonly coexists with endometriosis.25 There is often a history of ‘frequent UTI’ managed with antibiotics, but with negative urine culture. Urine may show WBC or RBC. Pelvic floor dysfunction secondary to IC, with painful intercourse, cervical smear tests and tampon use is common.

Sharp, stabbing, burning or aching pain (neuropathic pain)

Dysmenorrhoea and ‘period-like’ pain

Bowel dysfunction

(See Ch 30, Gastroenterology.)

Bloating

Premenstrual bloating is common before a period and should resolve post menses.

For all bloating, exclude an ovarian tumour with vaginal examination or ultrasonography.

Dyspareunia

Pelvic muscle pain

WHEN TO REFER FOR LAPAROSCOPY

PSYCHOLOGICAL SUPPORT / PSYCHOLOGIST

MENSTRUAL MIGRAINE

Migraines are more common in women, in families and in women with endometriosis.29 Menstrual migraines are migraines occurring with periods. Commonly there is a chronic low-grade headache at other times of the month too (chronic migraine), which may not be recognised as a migraine process. Headaches at the back of the head, associated with nausea, one-sided pain when severe, tender areas near the temples, pain behind the eyes, headaches on waking or pain worse with movement are all suggestive of a migraine-like process. Migraines in young children are common, and in girls they become even more common after menarche.

AETIOLOGY

INVESTIGATIONS

A typical history of migraine at menses does not require further investigation, unless:

TREATMENT

Avoiding migraine triggers

Specific treatments for menstrual migraine

For women whose menstrual migraines are due to a fall in oestrogen levels at menses:

The oral contraceptive pill (OCP) is relatively contraindicated in:

Management of chronic migraine

Diet

Herbal

Vitex agnus castus (chaste tree)

Vitex agnus castus is an effective treatment for common PMS symptoms, including headache.33

Pharmacological

Common medications useful in young women include:

Management of acute migraine

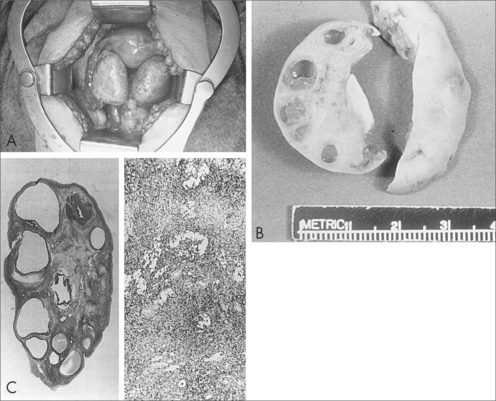

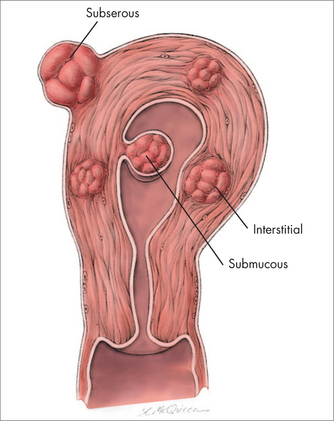

LEIOMYOMAS (FIBROIDS)

Leiomyomas are benign tumours of smooth muscle, commonly found in the uterus.

INCIDENCE AND NATURAL HISTORY

During pregnancy, myomas usually grow little and do not affect the pregnancy.

AETIOLOGY

The aetiology is unknown. Myomas are monoclonal. Chromosomal abnormalities are common (e.g. 12, 14 translocations, 7 deletions and trisomy 12), especially in cellular, atypical or large myomas.38

Myoma initiation may involve intrinsic abnormalities of the myometrium, congenitally elevated myometrial oestrogen receptors, hormonal changes or a response to ischaemic injury at the time of menstruation.39

MYOMA CLASSIFICATION

SYMPTOMS

Most uterine myomas are asymptomatic.

INVESTIGATIONS

TREATMENT

MYOMAS, FERTILITY AND PREGNANCY

Growth during pregnancy or obstetric complications are uncommon. However:

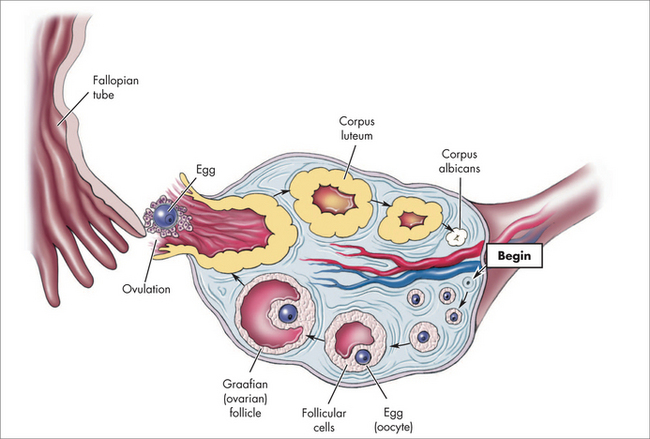

OVARIAN CYSTS (EXCLUDING POLYCYSTIC OVARIAN SYNDROME)

The ovary may contain a wide variety of cysts or tumours. Commonly, they include:

SYMPTOMS

Many functional cysts are asymptomatic. Hormonal effects including menstrual irregularity, nausea, vomiting or breast tenderness are common and mimic early pregnancy. Ovarian cyst rupture may occur, with sudden acute pain spontaneously or after intercourse. The pain improves over a few hours but may be followed by an ache for a few days.

Ovarian cysts of any kind may cause:

Women with endometriomas may describe typical symptoms of endometriosis or be asymptomatic.

INVESTIGATIONS

Radiological

CT scans assess the extent of metastatic disease.

MRI may be used to assess bowel or bladder infiltration in the presence of endometriomata.

Biochemical

Pregnancy test

Where positive, consider haemorrhage in the corpus luteum of pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy.

Cancer antigen 125

Cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) levels are frequently raised in:

Other tumour markers used to distinguish benign from malignant disease are discussed below.

An RMI 1 score > 200 has a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 92% and positive predictive value of 83%47 for ovarian malignancy.

TREATMENT

OVARIAN CYSTS AFTER MENOPAUSE

The incidence of ovarian cancer increases with increasing age, and functional cysts are less likely, so referral to a gynaecologist without repeat scan is appropriate, especially where ultrasound features are complex.

GYNAECOLOGICAL MALIGNANCIES

Gynaecological malignancies occur in 9.2% of women. The risk is 1:34 by age 75 years and 1:24 by age 85 years (Table 52.2).49

TABLE 52.2 Rate of gynaecological malignancies at ages 75 and 85 years

| Type of malignancy | Incidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Age 75 years | Age 85 years | |

| Ovary | 1:123 | 1:81 |

| Fallopian tube | rare | rare |

| Uterus | 1:74 | 1:54 |

| Cervix | 1:191 | 1:149 |

| Vagina | 1:2715 | 1:1343 |

| Vulva | 1:856 | 1:406 |

UTERINE CANCER

The histology of uterine cancer includes:

Risk and protective factors

Most risk factors involve unopposed oestrogen stimulation. They include:

Examination

Commonly the uterus, vagina and cervix are normal to examination. In advanced disease there may be an enlarged uterus or pelvic mass. Exclude other causes of bleeding (e.g. vulval, vaginal and cervical lesions). Take a cervical smear.

Investigations

Treatment

OVARIAN TUMOURS

RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR OVARIAN CANCER

Initial concern regarding the use of clomiphene for ovulation induction and risk of ovarian cancer has not been substantiated54 but remains under review.

HEREDITARY CANCER SYNDROMES

The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is:

By the age of 60, a woman with BRCA1 or 2 genes has a higher chance of developing cancer of the ovary in the next year than cancer of the breast.50

SCREENING

The value of screening in women in the general population is not established.56 Screening in women at high risk may be beneficial. Screening options include:

A combination of all three methods may be the most effective.

OVARIAN TUMOUR MARKERS

SYMPTOMS

Many ovarian tumours are initially asymptomatic. Symptoms include:

MANAGEMENT

For benign tumours, surgical removal alone is usually sufficient.

For further information on integrative and lifestyle management, see Ch 24, Cancer.

CERVICAL CANCER

RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS

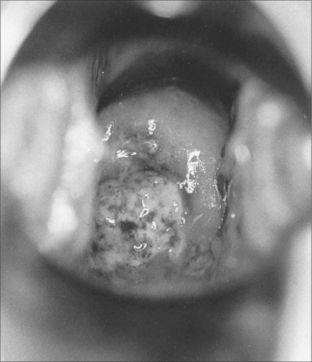

EXAMINATION

Very early lesions appear as a rough, reddish, area that bleeds on touch.

MANAGEMENT

Management depends on surgical staging, which frequently requires examination under anaesthesia.

VAGINAL CANCER

CANCER OF THE VULVA

EXAMINATION

DIETHYLSTILBOESTROL EXPOSURE

Women exposed in utero to DES require regular gynaecological review.

CARE OF WOMEN WITH GYNAECOLOGICAL CANCER

PSYCHOLOGIST

In addition to the concerns that all cancer patients share, specific gynaecological issues include:

SEXUAL CONCERNS

Sexual concerns are frequent and include:

FERTILITY SPECIALIST

Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Screening to prevent cervical cancer: guidelines for the management of asymptomatic women with screen-detected abnormalities. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/wh39syn.htm.

Endometriosis Association (Qld) Inc. (QENDO), support line, website and information. http://www.qendo.org.au/.

Endometriosis.org website. http://www.endometriosis.org.

Evans S, Bush D. Endometriosis and other pelvic pain. Adelaide, Australia: authors; 2009. For information: http://www.drsusanevans.com

1 García-Closas R, Castellsagué X, Bosch X, et al. The role of diet and nutrition in cervical carcinogenesis: a review of recent evidence. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(4):629-637.

2 Fang CY, Miller SM, Bovbjerg DH, et al. Perceived stress is associated with impaired T-cell response to HPV16 in women with cervical dysplasia. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(1):87-96.

3 Salamonsen LA. Tissue injury and repair in the female human reproductive tract. Reprod. 2003;125(3):301-311.

4 Hickey M, Crewe J, Mahoney LA, et al. Mechanisms of irregular bleeding with hormone therapy: the role of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):3189-3198.

5 Bakour SH, Dwarakanath LS, Khan KS, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound scan in predicting endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(5):447-451.

6 Roemheld-Hamm B. Chasteberry. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:821-824.

7 Blumenthal M. German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. Commission E. The complete German Commission E monographs: therapeutic guide to herbal medicines. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council, 1998.

8 Munro MG, Mainor N, Basu R, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate and combination oral contraceptives for acute uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):924-929.

9 deVore GR, Owens O, Kase N. Use of intravenous Premarin in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding—a double-blind randomized control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59(3):285-291.

10 Goldrath MH. Uterine tamponade for the control of acute uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;147(8):869-872.

11 Proctor ML, Murphy PA. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;3:CD002124.

12 Zhu X, Proctor M, Bensoussan A, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005288.

13 Treloar SA, O’Connor DT, O’Connor VM, et al. Genetic influences on endometriosis in an Australian twin sample. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:701-710.

14 Heilier JF, Donnez J, Lison D. Organochlorines and endometriosis: a mini-review. Chemosphere. 2008;1(2):203-210.

15 Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Pt 1):965-974.

16 Tokushige N, Markham R, Russell P, et al. Different types of small nerve fibers in eutopic endometrium and myometrium in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(4):795-803.

17 Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(2):310-315.

18 Missmer SA, Chavarro JE, Malspeis S. A prospective study of dietary fat consumption and endometriosis risk. Hum Reprod. 2010; 23 Mar. [Epub ahead of print].

19 Wieser F, Cohen M, Gaeddert A. Evolution of medical treatment for endometriosis: back to the roots? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(5):487-499.

20 Mier-Cabrera J, Aburto-Soto T, Burrola-Méndez S. Women with endometriosis improved their peripheral antioxidant markers after the application of a high antioxidant diet. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:54.

21 Flower A, Liu JP, Chen S, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD006568.

22 Evans S, Bush D. Endometriosis and pelvic pain. Adelaide, Australia: authors, 2009.

23 Cobellis L, Razzi S, Fava A, et al. A danazol-loaded intrauterine device decreases dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(1):239-240.

24 Gillett W, Jones D. Chronic pelvic pain in women: role of the nervous system. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;4(2):149-163.

25 Paulson JD, Delgado M. The relationship between interstitial cystitis and endometriosis in patients with chronic pelvic pain. J S Lab Surg. 2007;11(2):175-181.

26 Forrest JB, Mishell DRJr. Breaking the cycle of pain in interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: toward standardization of early diagnosis and treatment: consensus panel recommendations. J Reprod Med. 2009;54(1):3-14.

27 White AR. A review of controlled trials of acupuncture for women’s reproductive health care. J Fam Plann Reproduct Health Care. 2003;29:233-236.

28 Levitt M. The other women’s movement. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Michael Levitt Balance Publications, 2008.

29 Nyholt DR, Gillespie NG, Merikangas KR, et al. Common genetic influences underlie comorbidity of migraine and endometriosis. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;33(2):105-113.

30 MacGregor A. Menstrual migraine. Fact sheet. City of London Migraine Clinic. Online. Available: http://ww2.migraineclinic.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/menstrual-migraine.pdf.

31 Taubert K. Magnesium in migraine. Results of a multicentre pilot study. Fortschr Med. 1994;112(24):328-330.

32 Peikert A, Wilimzig C, Kohne-Volland R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with oral magnesium: results from a prospective multi-center, placebo-controlled and double-blind randomized study. Cephalalgia. 1996;16(4):257-263.

33 Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective, randomised, placebo controlled study. BMJ. 2001;322(7279):134-137.

34 Ernst E, Pittler MH. The efficacy and safety of feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium): an update of a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2000;3(4A):509-514.

35 Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyomas in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100-107.

36 Schwartz SM, Marshall LM, Baird DD. Epidemiologic contributions to understanding the etiology of uterine leiomyomata. Review. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 5):821-827.

37 Baird DD, Dunson DB. Why is parity protective for uterine fibroids? Epidem. 2003;14(2):247-250.

38 Walker CL, Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids: the elephant in the room. Review. Science. 2005;308(5728):1589-1592.

39 Parker WH. Etiology, symptomatology, and diagnosis of uterine myomas. Review. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(4):725-736.

40 Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(3):588-594.

41 Sizzi O, Rossetti A, Malzoni M. Italian multicenter study on complications of laparoscopic myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(4):453-462.

42 Pritts EA. Fibroids and infertility: a systematic review of the evidence. Review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56(8):483-491.

43 Qidwai GI, Caughey AB, Jacoby AF. Obstetric outcomes in women with sonographically identified uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):376-382.

44 Goto A, Takeuchi S, Sugimura K. Usefulness of Gd-DTPA contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI and serum determination of LDH and its isozymes in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma from degenerated leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12(4):354-361.

45 Yazbek J, Aslam N, Tailor A, et al. A comparative study of the risk of malignancy index and the ovarian crescent sign for the diagnosis of invasive ovarian cancer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28(3):320-324.

46 Jacobs I, Bast RCJr. The CA 125 tumour-associated antigen: a review of the literature. Hum Reprod. 1989;4(1):1-12.

47 Tingulstad S, Hagen B, Skjeldestad FE, et al. Evaluation of a risk of malignancy index based on serum CA 125, ultrasound findings and menopausal status in the pre-operative diagnosis of pelvic masses. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103(8):826-831.

48 Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, et al. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD006134.

49 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia: an overview. AIHW, 2006.

50 South Australian Familial Cancer Unit Publication. Adelaide, Australia: Royal Adelaide Hospital, 2006.

51 Bakour SH, Dwarakanath LS, Khan KS, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound scan in predicting endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(5):447-451.

52 Creasman WT. Hormone replacement therapy after cancers. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(5):493-499.

53 Melin A, Sparén P, Bergqvist A. The risk of cancer and the role of parity among women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(11):3021-3026.

54 Brinton LA, Lamb EJ, Moghissi KS, et al. Ovarian cancer risk after the use of ovulation-stimulating drugs. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(6):1194-1203.

55 Riman T, Nilsson S, Persson IR. Review of epidemiological evidence for reproductive and hormonal factors in relation to the risk of epithelial ovarian malignancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(9):783-795.

56 van Nagell JRJr, dePriest PD, Ueland FR, et al. Ovarian cancer screening with annual transvaginal sonography: findings of 25,000 women screened. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1887-1896.

57 Beral V, Million Women Study Collaborators, Bull D, Green J, Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and hormone replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2007;369(9574):1703-1710.

58 Neves E, Castro M. An analysis of ovarian cancer in the Million Women Study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(7):410-413.

59 Donnez J, Martinez-Madrid B, Jadoul P, et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation: a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(5):519-535.

60 Seli E, Tangir J. Fertility preservation options for female patients with malignancies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17(3):299-308.

61 Oktay K, Sönmezer M. Fertility preservation in gynecologic cancers. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19(5):506-511.