Gynaecological oncology

Lesions of the vulva

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

VIN is categorized into usual VIN (classic VIN or Bowen’s disease) and differentiated VIN (d-VIN) based on the distinctive pathological features (Box 20.1). Usual VIN often occurs in young women between 30–50 years and is associated with cigarette smoking and human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. Patients can be asymptomatic, or they may complain of pruritus, pain, dysuria and ulceration. Lesions can be white, pink or pigmented, in the forms of plaques or papules. They are most frequently found in labia and posterior fourchette; 3–4% of usual VIN may progress to invasive disease.

Management

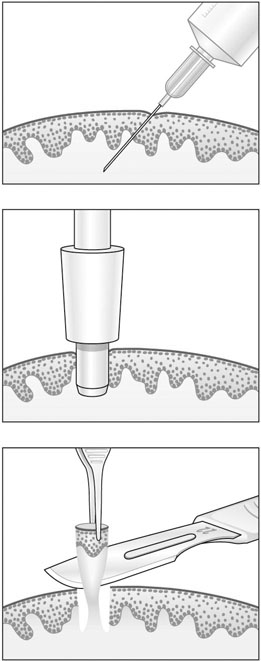

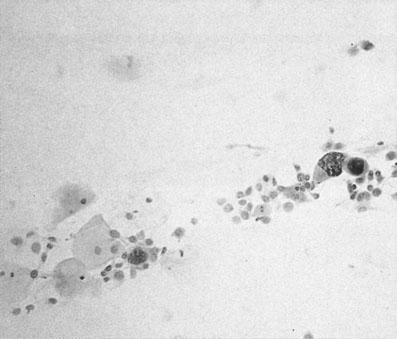

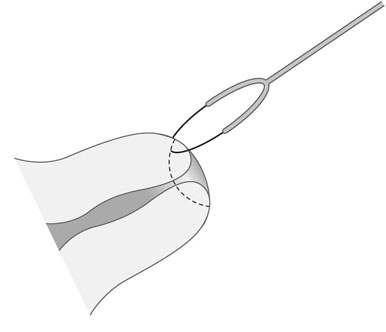

It is important to establish the diagnosis by biopsy (Fig. 20.1) and to search for intraepithelial neoplasia in other sites like the cervix and vagina, particularly when usual VIN is found. Treatment of usual VIN includes imiquimod, an immune modifier, laser therapy, and superficial excision of the skin lesion. There is no role for medical treatment in d-VIN, and surgical excision tends to be more radical than that for usual VIN. Recurrence is common and because there is a risk of malignant progression especially in d-VIN, long-term follow-up is essential.

Cancers of the vulva

Symptoms

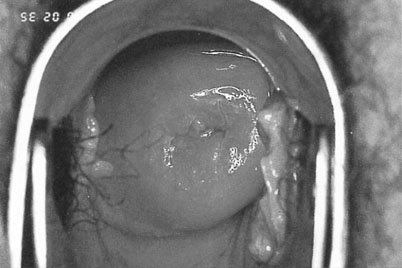

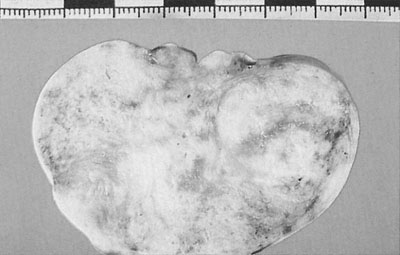

The patient with vulval carcinoma experiences pruritus and notices a raised lesion on the vulva, which may ulcerate and bleed (Fig. 20.2). Malignant melanomas are usually single, hyperpigmented and ulcerated. Vulval carcinoma most frequently develops on the labia majora (50% of cases) but may also grow on the prepuce of the clitoris, the labia minora, Bartholin’s glands and in the vestibule of the vagina.

Mode of spread

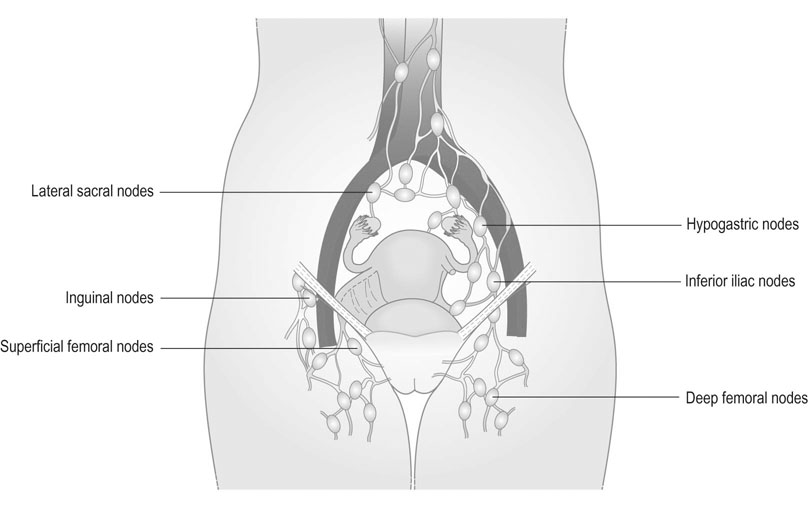

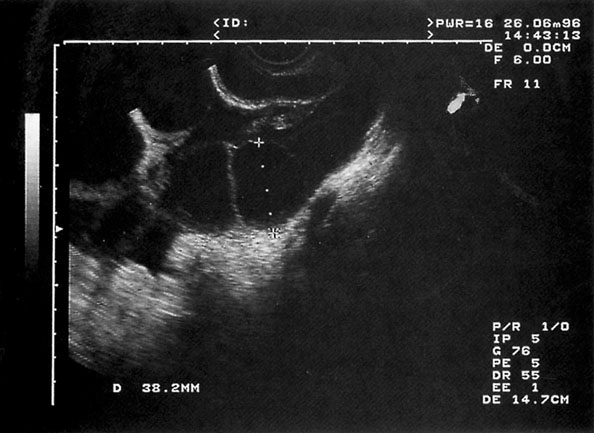

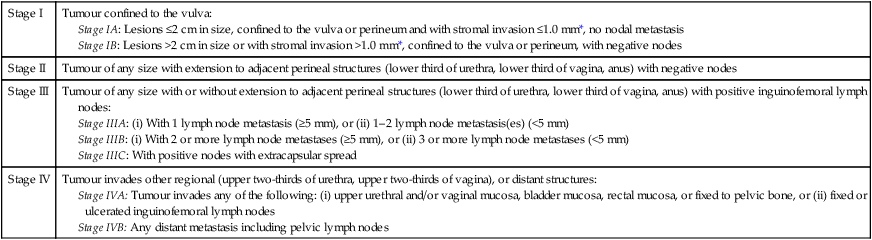

Spread occurs both locally and through the lymphatic system. The lymph nodes involved are the superficial and deep inguinal nodes and the femoral nodes (Fig. 20.3). Pelvic lymph nodes, except in primary lesions involving the clitoris, have usually only secondary involvement. Vascular spread is late and rare. The disease usually progresses slowly and the terminal stages are accompanied by extensive ulceration, infection, haemorrhage and remote metastatic disease. In some 30% of cases, lymph nodes are involved on both sides. Stages are defined by the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO) on the basis of surgical rather than clinical findings (Table 20.1).

Table 20.1

FIGO staging of vulval cancer (2009)

| Stage I | Tumour confined to the vulva:

Stage IA: Lesions ≤2 cm in size, confined to the vulva or perineum and with stromal invasion ≤1.0 mm*, no nodal metastasis Stage IB: Lesions >2 cm in size or with stromal invasion >1.0 mm*, confined to the vulva or perineum, with negative nodes |

| Stage II | Tumour of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower third of urethra, lower third of vagina, anus) with negative nodes |

| Stage III | Tumour of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower third of urethra, lower third of vagina, anus) with positive inguinofemoral lymph nodes: |

*The depth of invasion is defined as the measurement of the tumour from the epithelial stromal junction of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion.

Treatment

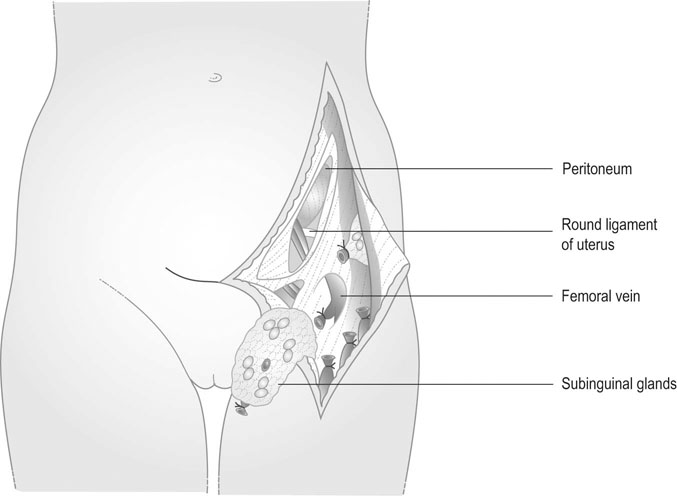

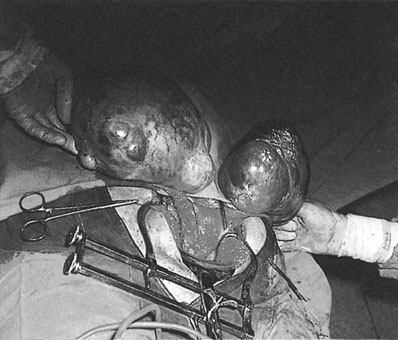

Stage IA disease can be treated by wide local excision. Stage IB lesions that are at least 2 cm lateral to the midline are treated by wide local excision and unilateral groin node dissection. All other stages are treated by wide radical local excisions or radical vulvectomy and bilateral groin node dissection (Fig. 20.4). Sentinel node dissection may replace conventional node dissection in future. Postoperative radiotherapy has a role in patients where the tumour extends close to the excision margin or there is involvement of the groin nodes. Preoperative radiotherapy may be used in cases of extensive disease to reduce the tumour volume. Complications of radical vulvectomy and groin node dissection include wound breakdown, lymphocyst and lymphoedema (30%), secondary bleeding, thromboembolism, sexual dysfunction and psychological morbidity. Response to chemotherapy (bleomycin) is generally poor. Patients are followed up at intervals of 3–6 months for 5 years.

Neoplastic lesions of the vaginal epithelium

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

Vaginal malignancy

Treatment

The diagnosis is established by biopsy of the tumour. Staging is made before commencing treatment (Table 20.2).

Table 20.2

Clinical staging of vaginal carcinoma

| Stage 0 | Intraepithelial carcinoma |

| Stage I | Limited to the vaginal walls |

| Stage II | Involves the subvaginal tissue but has not extended to the pelvic wall |

| Stage III | The tumour has extended to the lateral pelvic wall |

| Stage IV | The lesion has extended to involve adjacent organs (IVA) or has spread to distant organs (IVB) |

Lesions of the cervix

Screening for cervical cancer

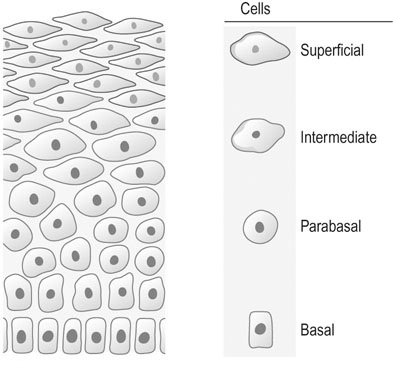

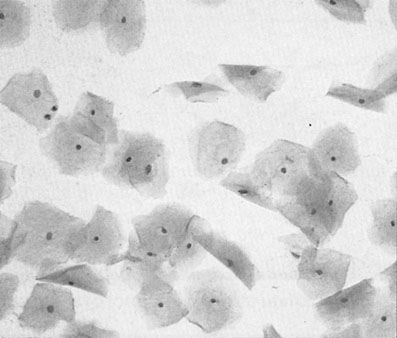

The aim of cervical screening programmes is to detect the non-invasive precursor of cervical cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), in the asymptomatic population in order to reduce mortality and morbidity. The NHS national cervical screening programme was introduced in England and Wales in 1988, and by 1991 80% of all women between the ages of 20 and 65 were being tested on a 5-yearly basis. Since then mortality from cervical cancer has fallen by 7% a year. Currently all women aged between 25 and 65 are invited for screening every 3–5 years. In Australia screening commences at the age of 18 or 2 years after the start of sexual activity and takes place every 2 years. In taking a cervical cytology, the speculum should be introduced with a minimum of artificial lubricant. Cells are taken from around the cervix from the whole of the transformation zone with a 360° sweep using an Ayres or Aylesbury spatula or a plastic cervical brush and fixed in an appropriate manner (see Chapter 15). Cervical cytology (Figs 20.5 and 20.7) is primarily for screening for squamous lesions and cannot reliably exclude endocervical disease.

Classification of cervical cytology

The terminology used in the UK for reporting cervical smears was introduced by The British Society for Clinical Cytology in 1986 (Table 20.3).

Table 20.3

Classification of cervical smears

| UK system | US Bethesda system |

| Negative | Within normal limits |

| Borderline nuclear change | ASCUS/ASC-H/possible low-grade SIL |

| Wart virus change | Low-grade SIL |

| Mild dyskaryosis | Low-grade SIL |

| Moderate dyskaryosis | High-grade SIL |

| Severe dyskaryosis | High-grade SIL |

| Glandular neoplasia | |

| Possible invasive cancer | Invasive cancer |

| Inadequate samples |

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells (high-grade), SIL, squamous intraepithelial lesion.

and exhibit degrees of nuclear changes before malignancy (Fig. 20.7). Cells showing abnormalities that fall short of dyskaryosis are described as borderline. Atypical glandular cells may represent premalignant disease of the endocervix or endometrium.

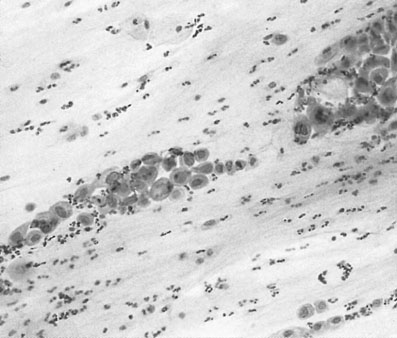

Malignant cells show nuclear enlargement at the expense of cytoplasmic mass (Fig. 20.8). The nuclei may assume a lobulated outline. There is increased intensity of staining of the nucleus and an increase in the number of mitotic figures.

The Bethesda system of classification used in the US (Table 20.3) differs by combining moderate and severe dyskaryosis as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) and using the term atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) instead of borderline. In the current edition of the classification system, the emphasis is to try and separate out borderline cases that may potentially be a high-grade lesion. This group of borderline lesion is called atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H). A modified version of this classification is used in Australia and New Zealand with HSIL and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) but the term possible low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (PLSIL) and possible high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (PHSIL) being used instead of ASCUS and ASC-H, respectively.

Colposcopy

Colposcopy is inspection of the cervix using a binocular microscope with a light source. It is usually an outpatient procedure performed using a speculum to expose the cervix. Squamous neoplasia most often occurs in the areas adjacent to the junction of the columnar (velvety red) and squamous (smooth pink) epithelium or the squamo–columnar junction (SCJ). If this cannot be seen in its entirety, CIN cannot be excluded by colposcopic examination and a cone biopsy will be required.

Colposcopic appearances

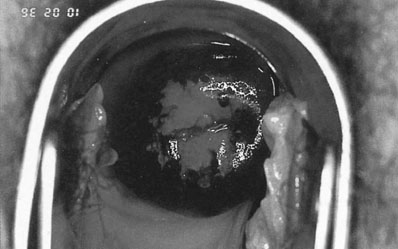

Neoplastic cells have an increased amount of nuclear material in relation to cytoplasm and less surface glycogen than normal squamous epithelium. They are associated with a degree of hypertrophy of the underlying vasculature. When exposed to 5% acetic acid the nuclear protein will be coagulated, giving the neoplastic cells a characteristic white appearance (Fig. 20.9). Small blood vessels beneath the epithelium may be seen as dots (punctation) or a crazy paving pattern (mosaicism) due to the increased capillary vasculature. The neoplastic cells do not react with Lugol’s iodine (Schiller’s test), unlike the normal squamous epithelium that will stain dark brown (Fig. 20.10). The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsies taken from the most abnormal-looking areas. Early invasive cancer is characterized by a raised or ulcerated area with abnormal vessels, friable tissue and coarse punctation with marked mosaicism. It feels hard on palpation and often bleeds on contact. In more advanced disease the cervix becomes fixed or replaced by a friable warty looking mass (Fig. 20.11).

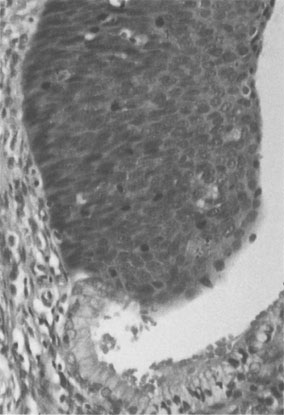

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

This is a histological diagnosis, usually made from colposcopic-directed biopsy, of changes in the squamous epithelium characterized by varying degrees of loss of differentiation and stratification and nuclear atypia (Fig. 20.12). It may extend up to 5 mm below the surface of the cervix by involvement of crypt epithelium in the transformation zone, but does not extend beyond the basement membrane. The aetiology is the same as that of invasive disease but with a peak incidence 10 years earlier. In the UK CIN is graded as mild (CIN-1), moderate (CIN-2) or severe (CIN-3) depending on the proportion of the epithelium replaced by abnormal cells. Twenty-five per cent of CIN 1 will progress to higher grade lesions over 2 years, and 30–40% of CIN-3 to carcinoma over 20 years. Around 40% of low-grade lesions (CIN-1) will regress to normal within 6 months without treatment especially in the younger age group.

Treatment

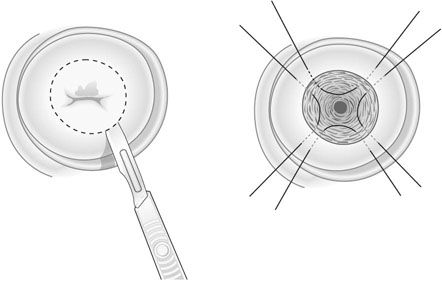

Destructive therapies include LASER ablation, cryocautery and coagulation diathermy. Ablative techniques are only suitable when the entire transformation zone can be visualized, there is no evidence of glandular abnormality or invasive disease, and there is no major discrepancy between the cytology and histology results. Excision can be carried out using scalpel, LASER or using a diathermy loop wire (large loop excision of the transformation zone, LLETZ; Fig. 20.13). LASER and LLETZ can be carried out under local anaesthetic. Ectocervical lesions can be adequately treated by removing tissue to a depth greater than 7 mm. When the SCJ cannot be seen or a lesion of the glandular epithelium is suspected, a deeper ‘cone’ biopsy is required to ensure that all of the endocervix is sampled (Fig. 20.14). Patients are advised to abstain from intercourse and not to use tampons for 4 weeks after treatment to reduce the risk of infection. Hysterectomy is rarely indicated for treatment of CIN but may be used if indicated for another reason such as heavy periods.

Cervical cancer

Pathology

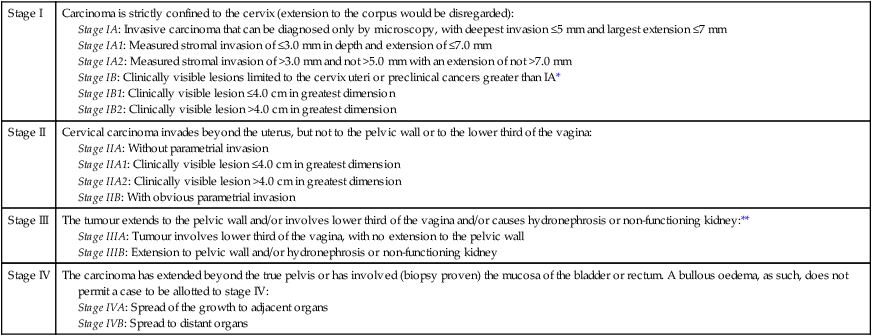

There are two types of invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Approximately 70–80% of lesions are squamous cell carcinoma and 20–30% adenocarcinomas. Histologically, the degree of invasion determines the stage of the disease (Table 20.4).

Table 20.4

FIGO classification of cervical cancer (2009)

*All macroscopically visible lesions – even with superficial invasion – are allotted to stage IB carcinomas. Invasion is limited to a measured stromal invasion with a maximal depth of 5.0 mm and a horizontal extension of not >7.0 mm. Depth of invasion should not be >5.0 mm taken from the base of the epithelium of the original tissue – squamous or glandular. The depth of invasion should always be reported in mm, even in those cases with ‘early (minimal) stromal invasion’ (~1 mm). The involvement of vascular/lymphatic spaces should not change the stage allotment.

**On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumour and the pelvic wall. All cases with hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney are included, unless they are known to be due to another cause.

Treatment of invasive carcinoma

Treatment is by surgery or radiotherapy/chemoradiation or a combination of both methods.

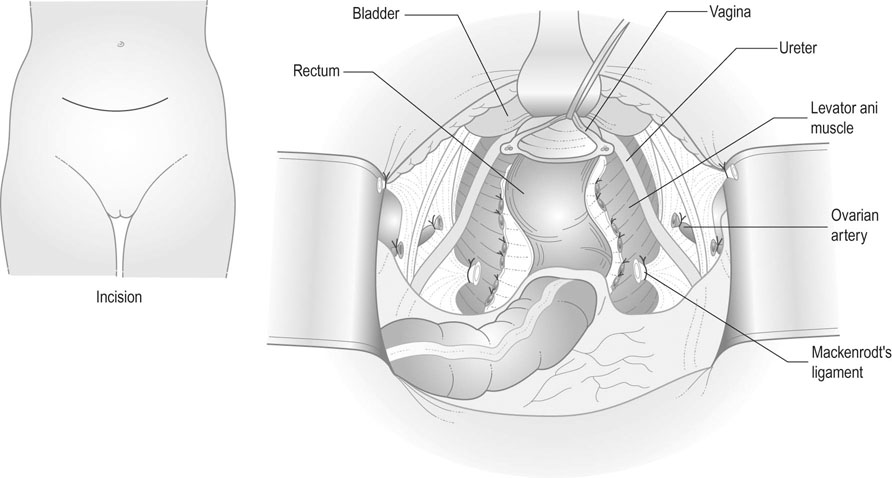

Surgery – radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection

Radical hysterectomy (Fig. 20.15) includes removal of the uterus, parametrium, and the upper third of the vagina. The ovaries may be conserved. This method of treatment, together with internal and external iliac and obturator lymph node dissection, is appropriate for patients with stage IB1 and early stage IIA1 diseases. Complications include haemorrhage, infection, pelvic haematomas, lymphocyst/lymphoedema, bladder dysfunction and damage to the ureters or bladder, which may result in fistula formation in 2–5% of cases. However, the incidence of vaginal stenosis is less than after radiotherapy, and so coital function is better preserved, making it the treatment of choice in the younger woman. Radical trachelectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection and prophylactic cervical cerclage can be considered in small stage IB1 tumour (less than 2 cm) if preservation of fertility is wished.

Malignant disease of the uterus

Endometrial carcinoma

Obesity: The ovarian stroma continues to produce androgens after the menopause, which are converted to oestrone in adipose tissue. This acts as unopposed oestrogen on the endometrium, resulting in endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy.

Obesity: The ovarian stroma continues to produce androgens after the menopause, which are converted to oestrone in adipose tissue. This acts as unopposed oestrogen on the endometrium, resulting in endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy.

Exogenous oestrogens: Unopposed oestrogen action, particularly as used for hormone replacement therapy in the menopause, is associated with an increased incidence of endometrial carcinoma. The addition of a progestogen for at least 10 days of each month can reduce this risk, and the combined oral contraceptive pill reduces the incidence of the disease.

Exogenous oestrogens: Unopposed oestrogen action, particularly as used for hormone replacement therapy in the menopause, is associated with an increased incidence of endometrial carcinoma. The addition of a progestogen for at least 10 days of each month can reduce this risk, and the combined oral contraceptive pill reduces the incidence of the disease.

Endogenous oestrogens: Oestrogen-producing ovarian tumours, such as granulose cell tumours are associated with an increase in the risk of endometrial cancer.

Endogenous oestrogens: Oestrogen-producing ovarian tumours, such as granulose cell tumours are associated with an increase in the risk of endometrial cancer.

Tamoxifen in breast cancer: Breast cancer patients on tamoxifen have a slightly increased risk of endometrial cancer, but most of these are detected in early stages and have good prognosis.

Tamoxifen in breast cancer: Breast cancer patients on tamoxifen have a slightly increased risk of endometrial cancer, but most of these are detected in early stages and have good prognosis.

Endometrial hyperplasia: Prolonged stimulation of the endometrium with unopposed oestrogen may lead to hyperplasia of the endometrium with periods of amenorrhoea followed by heavy or irregular bleeding. Endometrial hyperplasia can be classified into simple, complex and atypical hyperplasia. Women with atypical hyperplasia have an up to 50% chance of concurrent carcinoma and 30% chance of future progression to carcinoma. These women are usually treated by hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The risk of carcinoma in those with simple or complex hyperplasia without atypia is much lower (<5%). The majority of these women can be treated conservatively by progestogen therapy.

Endometrial hyperplasia: Prolonged stimulation of the endometrium with unopposed oestrogen may lead to hyperplasia of the endometrium with periods of amenorrhoea followed by heavy or irregular bleeding. Endometrial hyperplasia can be classified into simple, complex and atypical hyperplasia. Women with atypical hyperplasia have an up to 50% chance of concurrent carcinoma and 30% chance of future progression to carcinoma. These women are usually treated by hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The risk of carcinoma in those with simple or complex hyperplasia without atypia is much lower (<5%). The majority of these women can be treated conservatively by progestogen therapy.

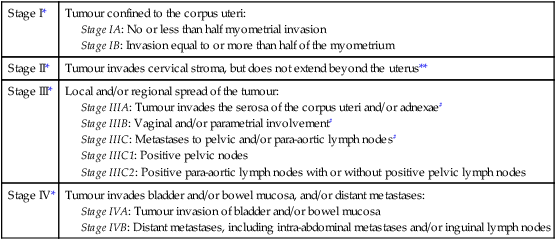

Prognosis

Endometrial cancer is surgically staged (Table 20.5). Prognosis largely depends on the stage of the disease as well as other prognostic factors that include age, histological subtype and grading. For stage I grade A, the 5-year survival can be over 90% for those with superficial myometrial invasion, but for those with deep myometrial invasion and grade III disease, the 5-year survival is only about 60% even if the disease is still confined to the uterus. For stage II, III and IV diseases, the 5-year survival is about 70–80%, 40–50% and 20%, respectively. Serous papillary and clear cell carcinomas have poorer prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of 50% and 35%, respectively.

Stage IIIA: Tumour invades the serosa of the corpus uteri and/or adnexae#

Stage IIIB: Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement#

Stage IIIC: Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes#

Stage IIIC1: Positive pelvic nodes

Stage IIIC2: Positive para-aortic lymph nodes with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes

**Endocervical glandular involvement only should be considered as Stage I and no longer as Stage II.

#Positive cytology has to be reported separately without changing the stage.

Malignant mesenchymal tumours of the uterus

Mixed müllerian tumours (carcinosarcomas)

These tumours (Fig. 20.17) consist of both epithelial and mesenchymal elements. The epithelial elements are usually endometrioid but can be squamous or a mixture. The stromal elements are either heterologous (chondroblastoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma) or homologous (leiomyosarcoma, presarcoma). The mean age at presentation is 65 years. An enlarged, irregular uterus with tumour protruding through the cervical os is a common finding at examination. Extrauterine spread occurs early and only 25% of patients have disease limited to the endometrium at the time of diagnosis.

Lesions of the ovary

Symptoms

• Abdominal enlargement – in the presence of malignant change, this may also be associated with ascites.

• Symptoms from pressure on surrounding structures such as the bladder and rectum.

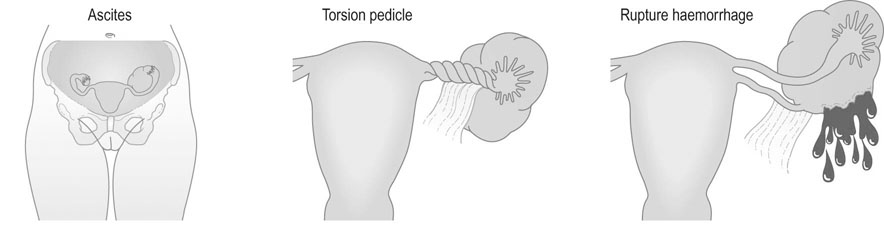

• Symptoms relating to complications of the tumour (Fig. 20.18). These include:

Torsion: Acute torsion of the ovarian pedicle results in necrosis of the tumour; there is acute pain and vomiting followed by remission of the pain when the tumour has become necrotic.

Torsion: Acute torsion of the ovarian pedicle results in necrosis of the tumour; there is acute pain and vomiting followed by remission of the pain when the tumour has become necrotic.

Rupture: The contents of the cyst spill into the peritoneal cavity and result in generalized abdominal pain.

Rupture: The contents of the cyst spill into the peritoneal cavity and result in generalized abdominal pain.

Haemorrhage into the tumour is an unusual complication but may result in abdominal pain and shock if the blood loss is severe.

Haemorrhage into the tumour is an unusual complication but may result in abdominal pain and shock if the blood loss is severe.

Hormone-secreting tumours may present with disturbances in the menstrual cycle. In androgen-secreting tumours the patient may present with signs of virilization. Although a greater proportion of the sex-cord stromal type of tumour (see below) are hormonally active, the commonest type of secreting tumour found in clinical practice is the epithelial type.

Hormone-secreting tumours may present with disturbances in the menstrual cycle. In androgen-secreting tumours the patient may present with signs of virilization. Although a greater proportion of the sex-cord stromal type of tumour (see below) are hormonally active, the commonest type of secreting tumour found in clinical practice is the epithelial type.

Benign ovarian tumours

Functional cysts of the ovary

These cysts occur only during menstrual life and rarely exceed more than 6 cm in diameter.

Follicular cysts

Follicular cysts (Fig. 20.19) are the commonest functional cysts in the ovary and may be multiple and bilateral. The cysts rarely exceed 4 cm in diameter, the walls consisting of layers of granulosa cells and the contents of clear fluid, which is rich in sex steroids. These cysts commonly occur during treatment with clomiphene or human menopausal gonadotrophin (Fig. 20.20). They may produce prolonged unopposed oestrogen effects on the endometrium, resulting in cystic glandular hyperplasia of the endometrium.

Lutein cysts

There are two types of luteinized ovarian cyst:

• Granulosa lutein cysts, functional cysts of the corpus luteum, may be 4–6 cm in diameter and occur in the second half of the menstrual cycle. Persistent production of progesterone may result in amenorrhoea or delayed onset of menstruation. These cysts often give rise to pain and therefore present a problem in terms of differential diagnosis, as the history and examination findings mimic tubal ectopic pregnancy. Occasionally, haemorrhage occurs into the cyst, which may rupture and lead to a haemoperitoneum. The cysts usually regress spontaneously and require surgical intervention only when they give rise to symptoms of intra-abdominal haemorrhage.

• Theca lutein cysts commonly arise in association with high levels of chorionic gonadotrophin and are therefore seen in cases of hydatidiform mole. The cysts may be bilateral and can, on occasion, give rise to haemorrhage if they rupture. Once the cysts have been formed, they can be detected by ultrasound. They usually undergo spontaneous involution but surgical intervention may be necessary if there is significant haemorrhage from the ovaries.

Benign neoplastic cysts

Sex cord stromal tumours

Hormone-secreting tumours of the ovary are a small but important group.

Granulosa cell tumours

Arising from ovarian granulosa cells, these tumours (Fig. 20.21) produce oestrogens and constitute some 3% of all solid ovarian tumours. Approximately 25% exhibit the characteristics of malignancy. As granulosa cell tumours can present at any age, the symptoms depend on the age of occurrence. Tumours arising before puberty produce precocious sexual development, and in women of the reproductive age, prolonged oestrogen stimulation results in cystic glandular hyperplasia and irregular and prolonged vaginal bleeding. Around 50% of cases occur after the menopause and present with postmenopausal bleeding. If the tumour is histologically benign, the surgery should be limited to oophorectomy. If there is evidence of malignancy, pelvic clearance is indicated.

Germ cell tumours

Tumours of germ cell origin may replicate stages resembling the early embryo.

Mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst)

Benign cystic teratomas account for 12–15% of true ovarian neoplasms. They contain a large number of embryonic elements such as skin, hair, adipose and muscle tissue, bone, teeth and cartilage (Fig. 20.22). Some of the components can be recognized on radiography.

Ovarian malignancy

Pathology

Primary ovarian carcinoma

The distribution of histological types of ovarian cancers is as follows.

Epithelial type

This makes up 85% of cases of ovarian malignancy. Epithelial tumours include the following subtypes:

• Serous cystadenocarcinoma is the most common histological type of ovarian carcinoma (40%) and is usually unilocular. They may be bilateral. These tumours are more likely to contain solid areas than their benign counterparts.

• Mucinous cystadenocarcinomas: These multicystic tumours (Fig. 20.23) are characterized by mucin-filled cysts lined by columnar glandular cells, and may be associated with tumours of the appendix.

• Endometrioid cystadenocarcinomas resemble endometrial adenocarcinomas and are associated with uterine carcinomas in 20% of cases.

• Clear-cell cystadenocarcinoma is the most common ovarian malignancy found in association with ovarian endometriosis. The unilocular thin-walled cysts are lined by epithelium with a typical hobnail appearance and clear cytoplasm.

• Brenner or transitional cell cystadenocarcinoma is often found in association with mucinous tumours but has a better prognosis than similar tumours arising from the bladder.

Tumours of low malignant or borderline potential account for 10–15% of primary epithelial carcinomas. They are commonly serous or mucinous tumours. There are cytological changes of malignancy including cellular atypia with increased mitosis and multilayering but without invasion. They have a significantly better prognosis than invasive disease, with a 5-year survival of more than 95% for stage I lesions but there is a 10–15% incidence of late recurrence.

Sex cord stromal tumours

These tumours are relatively rare as they make up only 6% of primary ovarian cancers.

• Granulosa cell tumours: These solid, unilateral, haemorrhagic tumours are the most common oestrogen-secreting lesions. They are characterized histologically by the presence of Call–Exner bodies.

• Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours: Approximately 25% of these are malignant, and may present with signs and symptoms of androgen excess.

Germ cell tumours

• Dysgerminomas: These solid tumours may be small or large enough to fill the abdominal cavity. The cut surface of the tumour has a greyish-pink colour and the microscopically, the tumour consists of large polygonal cells arranged in alveoli or nests separated by septa of fibrous tissue.

• Teratomas: The malignant or immature form of teratoma is most commonly solid, unilateral and heterogenous with multiple tissue elements. These tumours may produce human chorionic gonadotrophin, alpha-fetoprotein or thyroxine.

• Endodermal sinus or yolk sac tumours. Although these tumours make up only 10–15% of germ cell tumours, they are the most common germ cell tumour in children. They are solid, encapsulated tumours containing microcysts lined by flat mesothelial cells.

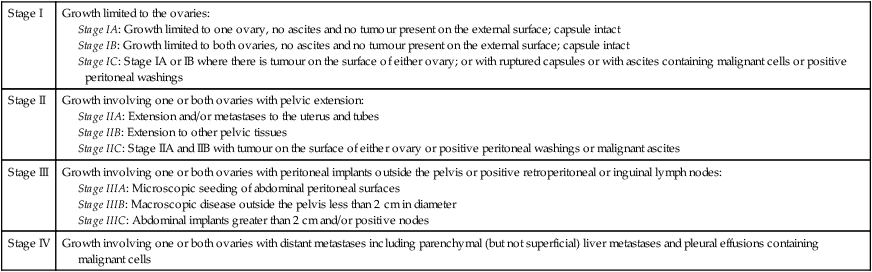

Staging of ovarian carcinoma

Spread of primary ovarian tumours can be by direct extension, lymphatics or via the bloodstream. Staging of ovarian carcinoma (Table 20.6) is important in determining both prognosis and the management. Ideally, it should be staged at the time of laparotomy with inspection and biopsy of the peritoneum and diaphragm, cytological examination of peritoneal fluid and pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes dissection.

Table 20.6

FIGO classification of ovarian carcinoma

Diagnosis

Early ovarian carcinomas are mostly asymptomatic. The commonest symptoms are abdominal discomfort or distension. Clinically, a pelvic mass may be detected and there may be ascites. An ultrasound scan can exclude other causes of pelvic mass such as fibroids and show features of malignant change (see below). A chest X-ray should be done to look for pleural effusions. CT or MRI scans (Fig. 20.24) may give an indication of spread. CA-125 is the widely used tumour marker for epithelial ovarian cancer. However, 15% of ovarian carcinomas will have normal levels and it is raised in only 50% of early stage disease.