2 Gynaecological examination

Pelvic examination

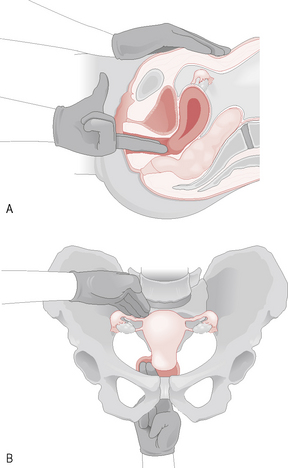

Both the Cusco’s and the Sims’ speculum examination should be followed by a bimanual examination. The patient lies in a similar position as for the Cusco’s speculum examination and the left hand parts the labia as two fingers are inserted into the vagina and then placed behind the cervix. The left hand is then placed on the abdomen above the symphysis pubis and pushes down onto the pelvis so that the organs are palpated between the left hand and the two fingers within the vagina. The uterus, which is situated centrally, should be assessed for size, consistency, mobility, regularity, anteversion, retroversion and tenderness. The adnexae are palpated on each side, particularly looking for tenderness and any suggestion of a mass. In very thin women normal-size ovaries may be felt (Fig. 2.1).

The area behind the cervix is palpated for any areas of tenderness or masses.

The pelvic examination occasionally needs to be concluded with a rectal examination if indicated.