Gynaecological disorders

Benign conditions of the upper genital tract

The uterus

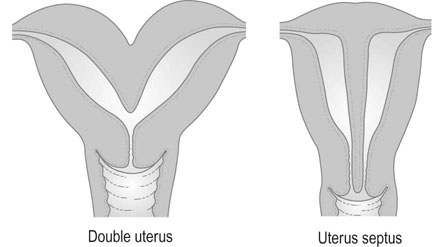

The formation of the uterus results from the fusion of the two Müllerian ducts; this fusion gives rise to the upper two-thirds of the vagina, the cervix and the body of the uterus. Congenital anomalies arise from the failure of fusion, or absence or partial development of one or both ducts. Thus, the anomalies may range from a minor indentation of the uterine fundus to a full separation of each uterine horn and cervix (Fig. 16.1). These conditions are also commonly associated with vaginal septa.

Symptoms and signs

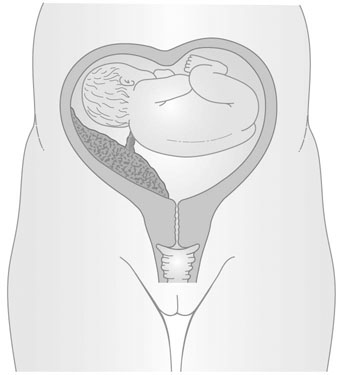

The presence of a double uterus may also be established at routine vaginal examination, when a double cervix may be seen. The separation of the uterine horns is sometimes palpable on bimanual vaginal examination, but in most cases the uterus feels normal and there is a single cervix. When only one horn is present, the uterus may be palpable as lying obliquely in the pelvis. The abnormality of two uterine horns and one cervix is known as uterus bicornis unicollis (Fig. 16.2).

The complications of pregnancy include:

• recurrent miscarriage: the role of congenital abnormalities in early pregnancy loss is unclear. For example, the incidence of uterine septa is the same in women with normal reproductive histories. However, there is an association with cervical incompetence, which may lead to mid-trimester miscarriage. This problem is usually associated with the subseptate uterus and is not common in the unicornuate uterus or in uterus bicornis bicollis

Surgical treatment

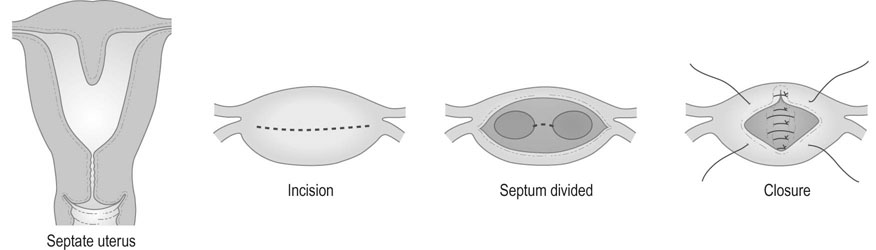

The operation of plastic reconstruction of the uterus with unification of two uterine horns or excision of the uterine septum is known as metroplasty (Fig. 16.4). An incision is made across the fundus of the uterus between the uterotubal junctions, taking care not to involve the intramural portion of the tube. The cavities are then reunited by suturing the surfaces together in the anteroposterior plane. If there is a septum, it is simply divided by diathermy and the cavity is then closed by suturing the transverse incision in the anteroposterior plane. Surgery of this type is associated with postoperative infertility in some cases and with a risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancy.

Endometrial polyps

Signs

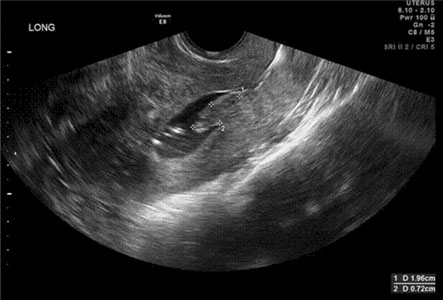

EPs are usually detected during the investigation for abnormal uterine bleeding and infertility. If the polyp protrudes through the cervix, it may be difficult to distinguish from an endocervical polyp (Fig. 16.5). EPs can be visualized on ultrasound. They are most easily detected in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle when the non-progestational type of glands in the polyp stand out in contrast to the normal surrounding secretory endometrium. If their presence is suspected either clinically or on transvaginal ultrasound, further clarification can be undertaken by performing a transvaginal sonohysterography (Fig. 16.6) and/or office or inpatient hysteroscopy with or without directed excisional biopsy.

Benign tumours of the myometrium

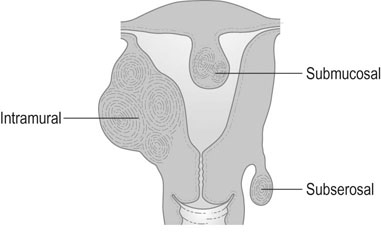

Uterine fibroids (myomas) are the most common benign tumour of the female genital tract and are clinically apparent in around 25% of women. They are smooth muscle tumours that vary enormously in size from microscopic growths to large masses that may weigh as much as 30–40 kg. Fibroids may be single or multiple and may occur in the cervix or in the body of the uterus. There are three types of fibroids according to their anatomical location. The most common are within the myometrium (intramural fibroids). Those located on the serosal surface that extend outwards and deform the normal contour of the uterus are subserosal fibroids. These may also be pedunculated and only connected by a small stalk to the serosal surface (Fig. 16.7). Fibroids that develop near the inner surface of the endometrium and extend into the endometrial cavity, either causing a distortion of the cavity or filling the cavity if they are pedunculated are submucous fibroids. Cervical fibroids are similar to other sites in the uterus. They are commonly pedunculated but may be sessile and grow to a size that will fill the vagina and distort the pelvic organs.

Symptoms and signs

• Abnormal uterine bleeding: submucous and intramural fibroids commonly cause HMB. Submucous fibroids may cause irregular vaginal bleeding, particularly if associated with overlying endometritis or if the surface of the fibroid becomes necrotic or ulcerated. Although a rare occurrence, submucous fibroids may prolapse through the cervix resulting in profuse bleeding.

• Pain: pelvic pain is a fairly common symptom that may occur in association with the HMB. Acute pain is usually associated with torsion of the pedicle of a pedunculated fibroid, prolapse of a submucous fibroid through the cervix, or so-called ‘red degeneration’ associated with pregnancy where haemorrhage occurs within the leiomyoma, causing an acute onset of pain.

• Pressure symptoms: a large mass of fibroids may become apparent because of palpable enlargement of the abdomen or because of pressure on the bladder or rectum. Women may describe reduced bladder capacity with urinary frequency and nocturia. A posterior wall fibroid exerting pressure on the rectosigmoid can cause constipation or tenesmus.

• Complications of pregnancy: recurrent miscarriage is more common in women with submucous fibroids. Fibroids tend to enlarge in pregnancy and are more likely to undergo red degeneration. A large fibroid in the pelvis may obstruct labour or make caesarean section more difficult. There is increased chance of postpartum haemorrhage and the presence of fibroids increases the risk of threatened preterm labour and perinatal morbidity.

• Infertility: obvious fibroids are found in 3% of women with infertility, but ultrasound scanning demonstrates a substantially higher number. The proportion increases greatly with age (up to 50% by age of menopause). Up to 30% of women with uterine fibroids will have difficulty conceiving. Submucous and intramural fibroids are more likely to impair infertility than subserous ones. The mechanism may be mediated by mechanical, hormonal and local molecular regulatory factor effects.

The diagnosis can usually be confirmed by ultrasound scans of the pelvis. However, a solid ovarian tumour may occasionally be mistaken for a subserous fibroid and a fibroid undergoing cystic degeneration may mimic an ovarian cyst.

Management

Surgical treatment

Endoscopic resection of many submucous fibroids can be performed using the hysteroresectoscope, and resection of subserous and intramural myomas can often be accomplished using laparoscopic techniques. In skilled hands, these procedures tend to be associated with lower morbidity and recurrence rate compared to open procedures. If the fibroid is more than 3 cm in diameter, pre- or peri-operative measures such as use of GnRH analogues can used to reduce the size of the fibroid prior to surgery.

Adenomyosis

Pathology

Both transvaginal ultrasound and MRI show high levels of accuracy for the non-invasive diagnosis of moderate to severe adenomyosis, but MRI is the most sensitive technique (Fig. 16.8). The microscopic diagnosis is based on the presence of a poorly circumscribed area of endometrial glands and stroma invading the smooth muscle layers of the myometrium.

Lesions of the ovary

Ovarian enlargement is commonly asymptomatic, and the silent nature of malignant ovarian tumours is the major reason for the advanced stage of presentation. Ovarian tumours may be cystic or solid, functional, benign or malignant. There are common factors in the presentation and complications of ovarian tumours and it is often difficult to establish the nature of a tumour without direct examination. The diagnosis and management of ovarian neoplasms is discussed in more detail in chapter 20.

Symptoms

• Abdominal enlargement: in the presence of malignant change, this may also be associated with ascites.

• Symptoms from pressure on surrounding structures such as the bladder and rectum.

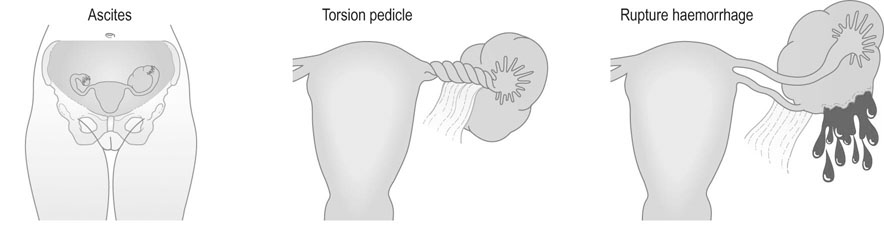

• Symptoms relating to complications of the tumour (Fig. 16.9); these include:

Torsion: acute torsion of the ovarian pedicle results in necrosis of the tumour; there is acute pain and vomiting followed by remission of the pain when the tumour has become necrotic

Torsion: acute torsion of the ovarian pedicle results in necrosis of the tumour; there is acute pain and vomiting followed by remission of the pain when the tumour has become necrotic

Rupture: the contents of the cyst spill into the peritoneal cavity and result in generalized abdominal pain

Rupture: the contents of the cyst spill into the peritoneal cavity and result in generalized abdominal pain

Haemorrhage into the tumour is an unusual complication but may result in abdominal pain and shock if the blood loss is severe

Haemorrhage into the tumour is an unusual complication but may result in abdominal pain and shock if the blood loss is severe

Hormone-secreting tumours may present with disturbances in the menstrual cycle. In androgen-secreting tumours the patient may present with signs of virilization. Although a greater proportion of the sex-cord stromal type of tumour (see below) are hormonally active, the commonest type of secreting tumour found in clinical practice is the epithelial type.

Hormone-secreting tumours may present with disturbances in the menstrual cycle. In androgen-secreting tumours the patient may present with signs of virilization. Although a greater proportion of the sex-cord stromal type of tumour (see below) are hormonally active, the commonest type of secreting tumour found in clinical practice is the epithelial type.

Endometriosis

Pathophysiology

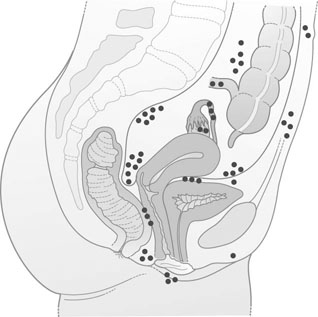

Aberrant endometrial deposits occur in many different sites (Fig. 16.10). Endometriosis commonly occurs in the ovaries (Fig. 16.11), the uterosacral ligaments and the rectovaginal septum. It may also occur in the pelvic peritoneum covering the uterus, tubes, rectum, sigmoid colon and bladder. Remote ectopic deposits of endometrium may be found in the umbilicus, laparotomy scars (Fig. 16.12), hernial scars, the appendix, vagina, vulva, cervix, lymph nodes and, on rare occasions, the pleural cavity.

Ovarian endometriosis occurs in the form of small superficial deposits on the surface of the ovary or as larger cysts known as endometriomas (Fig. 16.13) which may grow up to 10 cm in size. These cysts have a thick, whitish capsular layer and contain altered blood, which has a chocolate-like appearance. For this reason, they are known as chocolate cysts. Endometriomas are often densely adherent both to the ovarian tissue and to other surrounding structures.

The microscopic features of the lesions may be of endometrium (Fig. 16.14) that cannot be distinguished from the normal tissue lining the uterine cavity, but there is wide variation and, in many long-standing cases, desquamation and repeated menstrual bleeding may result in the loss of all characteristic features of endometrium. Underneath the lining of the cyst, there is often a broad zone containing phagocytic cells with haemosiderin. There is also a broad zone of hyalinized fibrous tissue. One of the characteristics of endometriotic lesions is the intense fibrotic reaction that surrounds them, and this may also contain muscle fibres. The intensity of this reaction often leads to great difficulty in dissection at the time of any operative procedure. The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains obscure. Sampson (1921) originally suggested that the condition was associated with retrograde spill of endometrial cells during menstruation and that some of these cells would implant under appropriate conditions in the peritoneal cavity and on the ovaries. This hypothesis does not account for endometriotic deposits outside the peritoneal cavity. An alternative theory suggests that endometrial lesions may arise from metaplastic changes in epithelium surfaces throughout the body.

Abnormal uterine bleeding

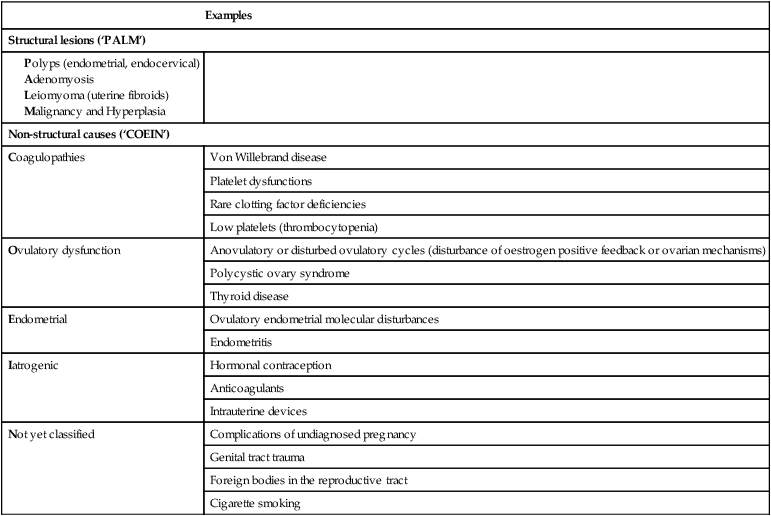

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is any bleeding disturbance that occurs between menstrual periods or is excessive or prolonged. This is the overarching term to describe any significant disturbance of menstruation or the menstrual cycle. FIGO (the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) has recently designed a classification system for underlying causes of AUB. This recommends that causes can be grouped under categories using the acronym PALM COEIN (Table 16.1). The most common menstrual abnormalities are intermenstrual (often associated with postcoital bleeding) and heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding.

Table 16.1

The FIGO recommendations on classification of causes underlying symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding

| Examples | |

| Structural lesions (‘PALM’) | |

(Reproduced from Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS, et al (2011) The FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in non-gravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynecol Obstet 113:3–13.)

Heavy menstrual bleeding

Investigations

• There is a history of repeated or persistent irregular or intermenstrual bleeding, or of risk factors for endometrial carcinoma.

• The cervical smear is abnormal.

• Pelvic examination is abnormal.

• There is significant pelvic pain unresponsive to simple analgesia.

• They do not respond to first-line treatment after 6 months.

Additional investigation is mainly to confirm or exclude the presence of pelvic pathology and in particular of endometrial malignancy. The main methods of investigation are ultrasound, endometrial biopsy, hysteroscopy and transvaginal ultrasound (with or without saline sonohysterography). Investigations for systemic causes of abnormal menstruation, such as a partial coagulation screen for the disorders of hemostasis – a coagulopathy – (of which mild von Willebrand Disease is the commonest of these causes associated with HMB) are only indicated if a screening history for coagulopathies is suggestive or in young women. Thyroid disease is a rare cause of HMB and investigation is only indicated if there are other features on examination or a previous history. Endometrial biopsy can be performed as an outpatient procedure either alone or in conjunction with hysteroscopy.

Management

Medical treatment

Hormonal treatments

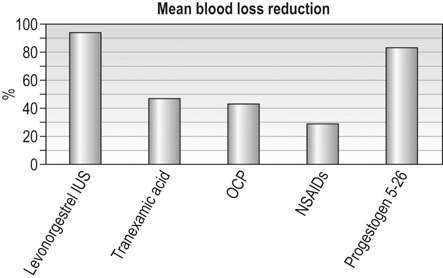

Use of the combined oral contraceptive pill or the levonorgestrel intrauterine system is associated with around 30% and 90% reduction in average monthly blood loss, respectively (Fig. 16.15). The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system is widely recommended as the first choice for medical therapy of HMB in those women who do not have contraindications to its use. Synthetic oral progestogens, such as norethisterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate, can be given for 21 days out of 28 over prolonged periods to effectively control irregular, heavy bleeding, but do tend to be associated with a higher incidence of nuisance-value side effects. They can also be used in higher doses in an acute situation to control severe heavy menstrual bleeding (oral norethisterone 5 mg, or medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg, three times daily for 21 days). Danazol is a synthetic mild impeded androgen derivative that acts on the hypothalamic–pituitary axis and endometrium, and is uncommonly used nowadays. Given at high doses it will normally cause amenorrhoea but is associated with significant side effects in 10% of patients. The efficacy of various medical therapies in reducing HMB is documented in Figure 16.15.

Surgical treatment

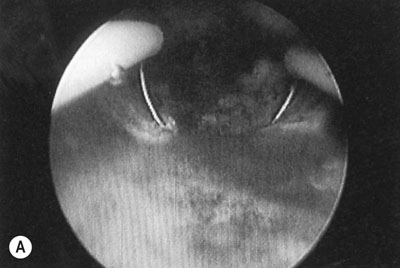

Endometrial resection or ablation

The endometrium can be removed or destroyed using an operating hysteroscope or with a number of modern third-generation intrauterine heating or cooling devices that ablate the endometrium. The first and second generation techniques involve using laser or diathermy resection with a wire loop or coagulation with a rollerball or a combination of the two (Fig. 16.16). The endometrium can be thinned prior to treatment with danazol or GnRH analogues for 4–8 weeks before surgery, allowing more effective ablation. The uterine cavity is distended with an irrigation fluid such as glycine or normal saline. There is a rare risk of intraoperative uterine perforation and, possibly, damage to other organs requiring laparotomy and repair. The other potential complication is fluid overload from excessive absorption of the irrigation fluid. Hysteroscopic procedures have now been largely replaced by newer semi-automatic techniques that do not require the same hysteroscopic skills. Balloon ablation involves inserting a fluid filled balloon into the endometrial cavity, which is then very precisely heated so that it destroys the entire endometrium. There are now a range of other devices, which are all based on the principle of excessively heating or cooling the endometrium using different energy sources, so that it is very precisely destroyed without damaging adjacent structures. Around 30–70% of patients will become amenorrhoeic, with a further 20–30% achieving major reduction in HMB. A minority of patients will eventually need further surgery and hysterectomy.

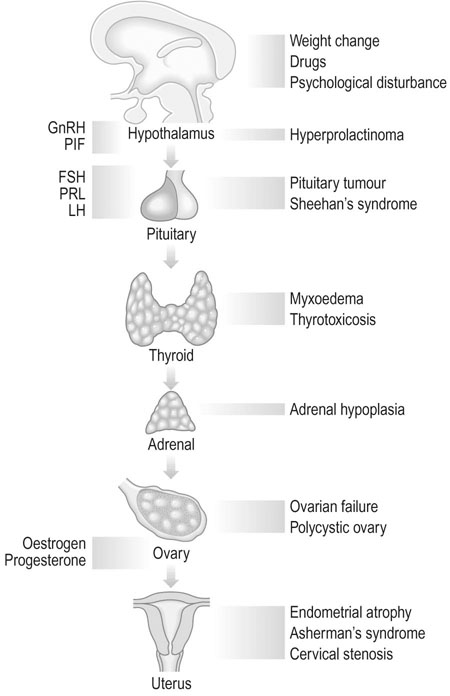

Secondary amenorrhoea and oligomenorrhoea

Aetiology

Physiological

Ovarian disorders

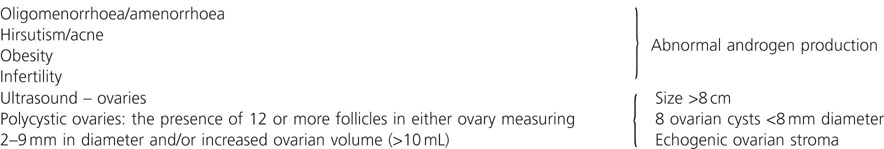

Polycystic ovary syndrome

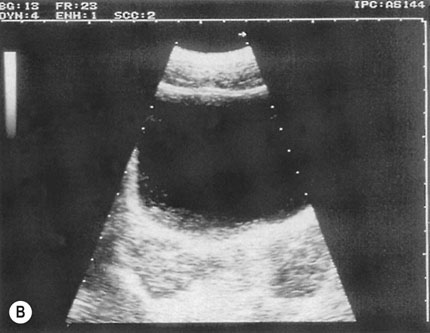

PCOS affects 5–10% of reproductive age women and is associated with 75% of all anovulatory disorders causing infertility and with 90% of women with oligomenorrhoea (Box 16.2). PCOS is found in women with symptoms of androgen excess: in 90% of women with hirsutism and 80% of women with acne. Approximately 50% of women with the condition are overweight or obese. PCOS was first described by American gynaecologists Irving Stein and Michael Leventhal in 1935 who noticed the association between polycystic ovaries, amenorrhoea and hirsutism. The ovaries in PCOS appear enlarged and contain multiple (more than 10–12), small (less than 10 mm) fluid-filled structures just under the ovarian capsule. These are small, normal antral and atretic follicles, and are not true ‘cysts’. They are present in much greater numbers than are present in the normal ovary, but they have the same functions as normal (Fig. 16.18). The PCO ovary also has a greatly increased ovarian stroma, which may have abnormal endocrine properties.

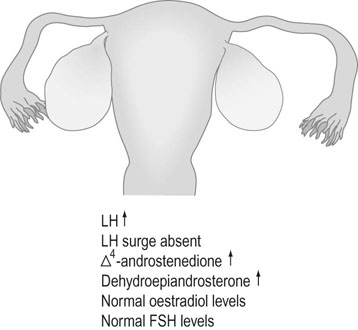

Biochemical investigations (Fig. 16.19) indicate abnormally raised LH levels and absence of the LH surge. Oestrogen and FSH levels are normal, and as a result there is an increase in the LH: FSH ratio. There may be increased ovarian secretion of testosterone, androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone. Prolactin levels are increased in 15% of cases.

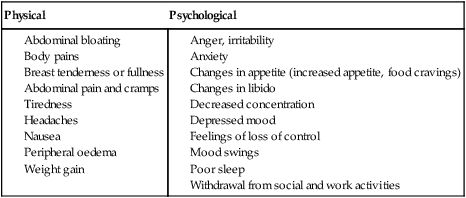

Premenstrual syndrome

Disorders of puberty

Puberty and menarche

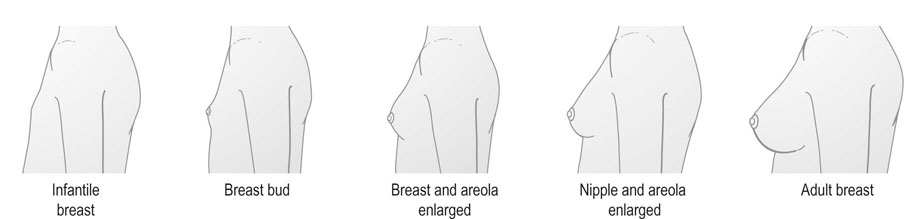

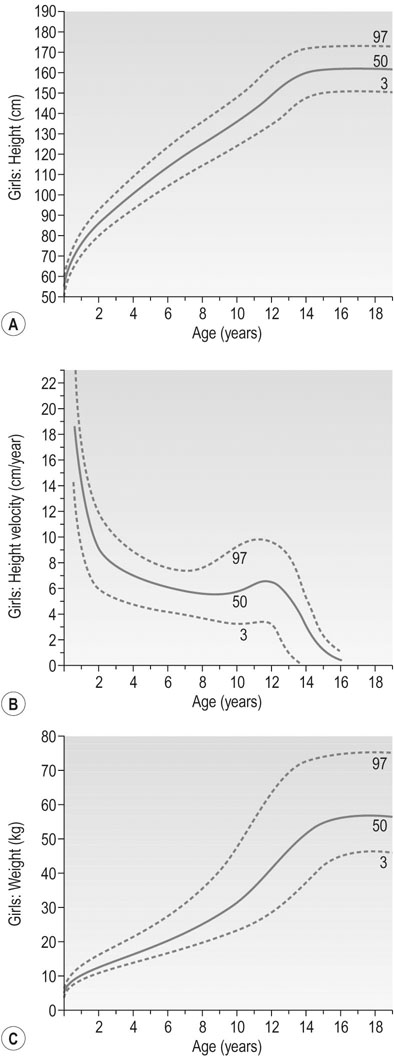

Puberty in females is characterized by accelerated linear growth, development of breasts, thelarche, axillary and pubic hair, adrenarche and eventual onset of menses, i.e. menarche (Figs 16.20 and 16.21). Generally, there is a forward progression through these stages. However several variations can occur such as premature thelarche or adrenarche. Puberty is complete once oestrogen rises to the level where positive feedback occurs on the hypothalamus and ovulatory cycles establish. The entire process is seen to vary in length considerably being between 18 months to 6 years.

Precocious puberty

Central (GnRH dependent) in order of frequency:

Patients with central precocious puberty have unregulated GnRH release. FSH and LH levels fluctuate so multiple samples may be required, remembering a propensity to nocturnal secretion. A GnRH stimulation test will show a pubertal, threefold response in LH levels. FSH also rises but to a lesser degree. In central precocious puberty the progression follows the usual pattern, albeit earlier.

Peripheral or GnRH independent causes:

• hormonal secreting tumour of the adrenal gland or ovaries

• gonadotrophin producing tumours

Evaluation

The first step in evaluating a girl with precocious puberty is to obtain a complete family history including the age of onset of puberty in parents and siblings. The heights of both parents should be recorded and the projected height of the child calculated (Fig. 16.22). The history of pubertal development needs to be documented and along with other symptoms such as headache or visual disturbance. A history of illness, trauma, surgery and medications is also pertinent. Physical examination should include documentation of the Tanner stage and examination for other signs to indicate a peripheral cause such as skin lesions or ovarian masses. Signs of virilization must be looked for including, acne, hirsutism and clitoromegaly.

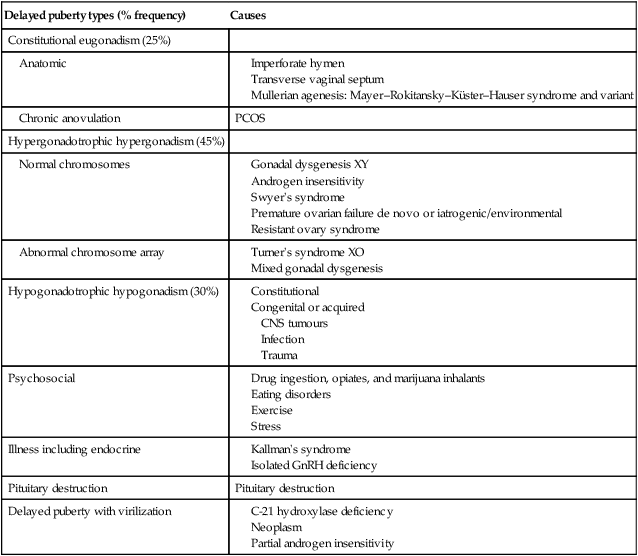

Delayed puberty

Delayed puberty is defined by the absence of breast development in girls beyond 13 years. The diagnosis is also made in the absence of menarche by age 16 or within 5 years after the onset of puberty. Mostly delayed puberty is constitutional, arising from inadequate GnRH from the hypothalamus. It may also be secondary to chronic illness such as anorexia nervosa, asthma, chronic renal disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Anatomic considerations such as outflow obstruction in haematocolpos need exclusion. The hypogonadism that characterizes this state may occur with both elevated and lowered levels of gonadotrophins. As with precocious puberty it is essential to establish the status of the gonadotrophins to determine causation (Table 16.3).

Table 16.3

Causes of delay in some aspect of puberty

| Delayed puberty types (% frequency) | Causes |

| Constitutional eugonadism (25%) | |

| Anatomic |

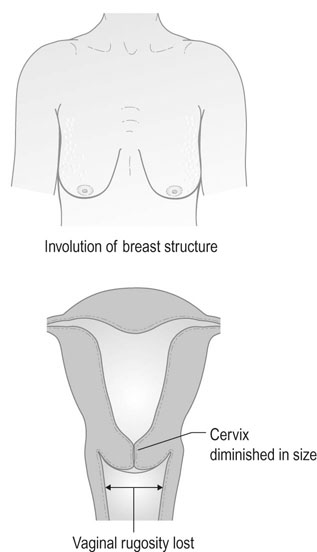

Menopause

Symptoms and signs of menopause

Physical symptoms

Consequences of menopause

Bone changes

• T-score greater than −1 indicates normal bone density.

• T-score between −1 and −2.5 indicates low bone density, sometimes called osteopoenia. This means there is some loss of bone mineral density, but not severe enough to be called osteoporosis.

• T-score of −2.5 or less indicates osteoporosis. When a person has a minimal impact fracture, regardless of the T-scores, osteoporosis is also diagnosed.

Treatment of the menopause

Many women pass through the menopause without any symptoms, and there is considerable variation in serum oestradiol levels between individuals after the menopause. Oestrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for symptomatic relief, but maybe associated with significant adverse effects in a small minority of women. The decision to use HRT is made on an individual basis taking into account each woman’s history, risk factors and personal preferences (Table 16.4). This should be done in a way that can be understood so that each woman can make an informed choice.

Table 16.4

Relative risks and benefits seen in women taking combined oestrogen and progestogen HRT

| Relative risk vs placebo group at 5 years | |

| Heart attacks | 1.29 |

| Stroke | 1.41 |

| Breast cancer | 1.26 |

| Venous thrombosis | 2.11 |

| Fractured neck of femur | 0.63 |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.66 |

(Adapted from Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized contolled trial. JAMA 2002; 288:321–333.)

Benign conditions of the lower genital tract

Vulval pruritus

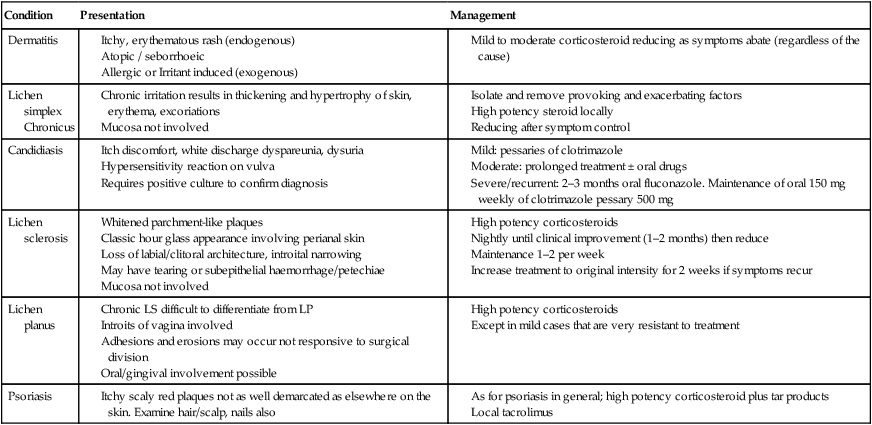

Fortunately the majority of causes of vulval pruritus are benign (Table 16.5). However, care must be taken not to overlook or misdiagnose the rarer malignant causes. The vulva is skin and therefore may express conditions seen elsewhere on the body, e.g. psoriasis, dermatitis. However because of the nature of this area the appearance of skin conditions may vary greatly. The vulva, in such proximity to the vagina, may also express features of bacterial or viral vaginitis or cervicitis with hypersensitivity reaction to productive discharge as seen in candidiasis. It is therefore extremely important when assessing a patient with pruritus of the vulva to take a very wide-ranging history to include personal and family history of skin conditions, autoimmune disease, exposures to possible irritants such as soaps, perfumes, sanitary products, etc. and to examine the rest of their skin. Particular attention should be paid to the scalp, elbows, anterior cubital fossae and knees. Inspection of the genitalia does not generally require colposcopic examination, but it is important to obtain bacterial and viral cultures both from vulval lesions and vaginal or cervical mucosa when indicated.

Table 16.5

Benign causes of vulval pruritus

| Condition | Presentation | Management |

| Dermatitis | ||

| Lichen simplex Chronicus |

||

| Candidiasis | ||

| Lichen sclerosis | ||

| Lichen planus | ||

| Psoriasis |

Vaginal discharge

Vaginal discharge describes any fluid loss through the vagina. While most discharge is normal and can reflect physiological changes throughout the menstrual cycle, some discharge can occur because of infection or trauma. White discharge usually occurs in response to hormonal changes at the beginning and the end of the cycle whilst midcycle, with high oestrogen levels, the discharge is clear. The common causes and management of vaginal discharge are summarized in Table 16.6. Further details on the common infections of the genital tract and their treatment can be found in in Chapter 19.

Table 16.6

Vaginal discharge: causes and treatment

| Features of discharge and associated symptoms | Possible causes | Treatment |

| Thick, white non itchy | Physiological | |

| Thick, white, cottage cheese, vulval itching, vulval soreness and irritation, pain or discomfort | Candida albicans | Topical or oral anti yeast medication |

| Yellow-green, itchy, frothy foul-smelling (‘fishy’ smell) vaginal discharge | Trichomonas | Metronidazole and treatment of sexual partners |

| Thin, grey or green, fishy odour | Bacterial vaginosis | Metronidazole |

| Thick white discharge, dysuria and pelvic pain, friable cervix | Gonorrhoea | Variable but cephalosporins |

Benign tumours of the vulva and vagina

Benign cysts of the vulva include sebaceous, epithelial inclusion and wolffian duct cysts (Fig. 16.24), which arise from the labia minora and the per-urethral region, and Bartholin’s cysts, see below. A rare cyst may arise from a peritoneal extension along the round ligament, forming a hydrocele in the labium major. Benign solid tumours include fibromas, lipomas and hidradenomas. True squamous papillomas appear as warty growths and rarely become malignant. All these lesions are treated by simple biopsy excision.

Emergency gynaecology

Pelvic infection

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) comprises a spectrum of inflammatory disorders of the upper female genital tract mainly caused by ascending infection from the cervix or vagina. Acute PID is covered in detail in Chapter 19.

Bartholin’s abscess/cyst

Small asymptomatic cysts may not require treatment and abscesses can sometimes resolve with antibiotics. However, treatment of large cysts and abscesses require surgery. The procedure, called marsupialization, involves making a pouch like opening to the gland by incising into the cyst wall and then suturing it to the overlying skin to ensure the new opening continues to drain the fluid from the glands (see Chapter 19, Fig. 19.13).

Acute abdominal pain of uncertain origin

It is important in the assessment of a woman with acute pelvic pain to exclude those diagnoses that require urgent intervention: PID, ovarian torsion and appendicitis. The investigation and diagnosis of PID has been discussed above. Ovarian torsion usually occurs in the presence of an enlarged ovary (see ovarian cysts in Chapter 20). Women with torsion present with sudden onset of sharp unilateral pelvic pain that is often accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The sonographic findings in ovarian torsion are variable. The ovary is enlarged and can be seen in an abnormal location above or behind the uterus. The absence of blood flow is an important sign and a lack of venous waveform on Doppler ultrasound has a high positive predictive value. However the presence of arterial and venous flow does not exclude torsion and any cases where it is suspected clinically require laparoscopy to visualize the adnexae. If the torsion is reversed early in the process the ovary may be saved.