Chapter 1 Gynaecological and obstetric history and examination

THE WOMAN PRESENTING WITH GYNAECOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

History

Examination

The gynaecological portion of the examination should include:

Breast examination

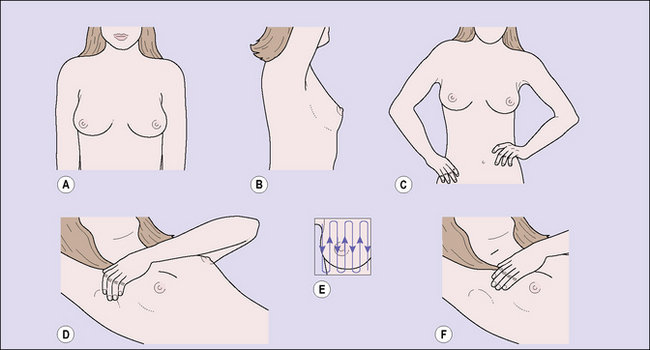

With the patient sitting facing the examiner, the breasts are inspected, first with the patient’s arms at her sides and then with her arms raised above her head (Fig. 1.1). The shape, contour and size of the breasts, their height on the chest wall, and the position of the nipples are compared, any nipple retraction being noted. The supraclavicular regions and axillae are next palpated. The latter can only be palpated satisfactorily if the pectoral muscles are relaxed. This relaxation can be obtained if the physician supports the patient’s arms while palpating the axillae. Palpation is then performed with the patient lying supine, her shoulders elevated on a small pillow. Palpation should be gentle and orderly, using the flat of the fingers of one hand. Each portion of the breast should be palpated systematically, beginning at the upper, inner quadrant, followed by palpation of each portion sequentially until the upper, outer quadrant is finally examined.

The breast self-examination that many doctors recommend to women is similar to the breast examination made by the doctor, except that the woman usually does not palpate the axillary area. Figure 1.1 demonstrates how a woman should examine her breasts. The technique can easily be taught to her by her doctor.

Pelvic examination

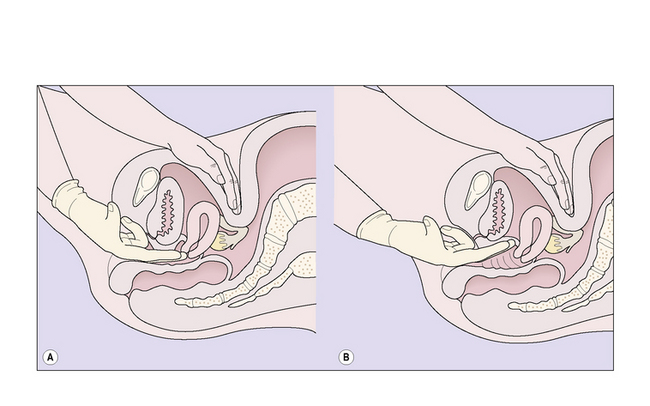

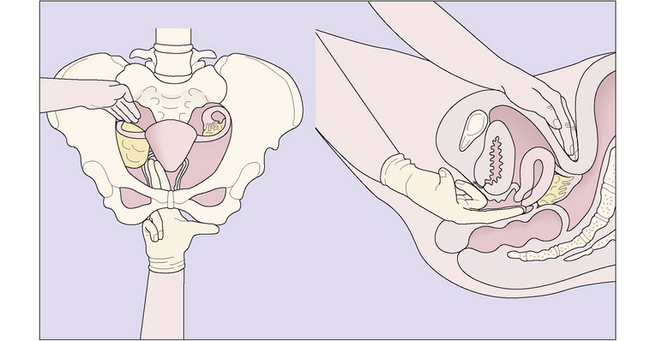

The patient is asked to strain down, to enable detection of any evidence of prolapse, after which a bivalve speculum is inserted and the cervix visualized. For the woman’s comfort the speculum should be warmed and the doctor’s approach sensitive and communicative. If the physician intends to take a cervical smear to examine the exfoliated cells, no lubricant apart from water should be used on the speculum. The vagina and cervix are inspected by opening the bivalve speculum (Fig. 1.2). If the patient has a prolapse, the degree of the vaginal wall or uterine descent can best be assessed if a Sims speculum is used, with the patient in the left lateral position (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3 The patient in the left lateral position; a Sims speculum has been inserted into the vagina.

Digital examination follows, one or two fingers of the gloved hand being introduced. For the right-handed person it is usual to use the right hand as the fingers of this hand are more ‘educated’, and vice versa for the left-handed person. After the labia minora have been separated with the left hand to expose the vestibule, the fingers are introduced, passing upwards and backwards to palpate the cervix. The left hand simultaneously palpates the pelvis through the abdominal wall, so that the uterus and ovaries may be palpated. Normal Fallopian tubes (oviducts) are never palpable. As the intravaginal fingers push the cervix backwards, the abdominally located hand is placed just below the umbilicus and the fingers reach down into the pelvis, slowly and smoothly, until the fundus is caught between them and the fingers of the right hand in the anterior vaginal fornix (Fig. 1.4).

The information obtained by bimanual examination includes:

Rectal examination

A rectal examination, or a rectoabdominal bimanual examination, may replace a vaginal examination in children and in virgin adults, but the examination is less efficient and more painful than the vaginal examination. A rectal examination is a useful adjunct to a vaginal examination when either the outer parts of the broad ligaments or the uterosacral ligaments require to be palpated. On occasion, a rectovaginal examination, with the index finger in the vagina and the middle finger in the rectum, may help to determine if a lesion is in the bowel or between the rectum and the vagina. Box 1.1 describes the skills required in performing a gynaecological examination.

Box 1.1 Patient–doctor skills needed during conduct of a gynaecological examination

Tests

Appropriate tests may be required. For example, if the woman complains of a vaginal discharge, swabs should be taken to determine the cause (see p. 293). Urinary symptoms may require a midstream specimen of urine to assist in reaching a diagnosis.

Investigations

Colposcopy

The colposcope is a low-powered microscope for inspecting the cervix and vagina in cases where abnormal cells have been detected by a Pap smear. The cervix and vagina are exposed by introducing a bivalve vaginal speculum. The colposcope is placed in front of the vagina and its focal length is adjusted to examine the suspect part of the lower genital tract (see p. 293).

Hysteroscopy

A small fibreoptic telescope is inserted through the cervix into the uterine cavity, which is inspected. The procedure may help the doctor to reach a diagnosis in cases of menstrual disorders. Endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids and intrauterine adhesions and septae can be removed and the endometrium ablated (see p. 225) using this technique.

THE MATERNITY PATIENT

History

The medical practitioner should enquire about these matters again during the pregnancy.

Examination

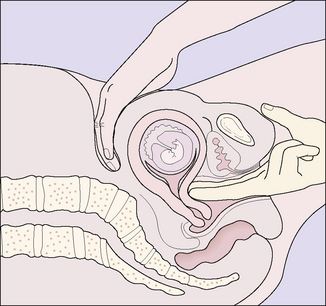

Having taken a history the doctor should examine the woman as described earlier, although a vaginal examination does not need to be performed. Indications for conducting a vaginal examination include a vaginal discharge, active bleeding and to take a Pap smear if it has not been done in the previous 12 months. If the doctor performs a vaginal examination between 6 and 10 weeks after the woman’s last menstrual period (LMP) the uterus may feel as if it is separate from the cervix. This is because the cervix has softened, and the examiner’s fingers seem to meet below the ball-shaped uterus (Hegar’s sign), as shown in Figure 1.6.

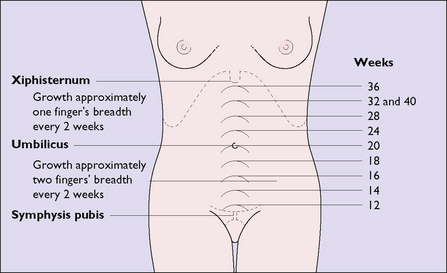

Most women seek to have the pregnancy confirmed during the first 10 weeks, but some delay until later. The uterus becomes palpable early in the second trimester (i.e. from 13 weeks’ gestation) on abdominal examination (Fig. 1.7) and fetal heart sounds can be heard using an ultrasonic heart detector at this time. The woman feels her fetus moving from about 18 weeks’ gestation.

Once pregnancy has been diagnosed further investigations should be made. These are discussed in Chapter 6.

Evidence of a previous pregnancy

However, a firm diagnosis cannot be given as these signs can be produced by other disorders.

Medicolegal aspects and patient–doctor communication

What can be done?

The doctor

The doctor should take the following measures to reduce litigation:

Operative procedures in obstetrics and gynaecological surgery

Ultimately, a reduction in litigation will occur if the doctor can communicate well with the patient, being sensitive to her concerns and answering her questions without showing any haste or impatience (Box 1.2).

Box 1.2 Doctor–patient communication

To achieve this the doctor should: