CHAPTER 4 Guidelines for Herbal Medicine Use

BOTANICAL MEDICINE SAFETY: GUIDELINES FOR PRACTITIONERS

Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of Americans use some type of herbal supplements, as many as 18% use them in conjunction with pharmaceutical drugs, and most do not inform their health care providers of herbal medicine use (see Chapter 1). 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Botanical medicine safety has, therefore, become a critical issue for practitioners, whether themselves prescribing herbal medicines in practice, or in caring for patients who are self-medicating with herbs.

Numerous and complex factors influence botanical medicine safety and risk, including:

Botanical medicine safety is a broad and complex subject, far larger than can be adequately addressed in a single chapter. Nonetheless, a text on botanical medicine would be incomplete without addressing this critical topic. This chapter provides an overview of the most pertinent botanical medicine safety concerns relevant to clinical practice. It is suggested that readers obtain additional references on this topic, recommendations for which appear in Table 4-1.

| BOTANICAL | AUTHOR/EDITOR | PUBLISHER |

|---|---|---|

| Texts | ||

| Adverse Effects of Herbal Drugs (three volumes) | DeSmet P. | Springer Verlag |

| Botanical Dietary Supplements: Quality, Safety, and Efficacy | Mahady, G., Fong H., Farnsworth N. | Swets and Zeilinger |

| Botanical Safety Handbook | McGuffin M., Hobbs C., Upton R., Goldberg A. | CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL |

| Commission E (translated) | Blumenthal M. (ed.) | American Botanical Council, Austin, TX |

| Expanded Commission E | Blumenthal M. (ed.) | American Botanical Council, Austin, TX |

| Herb-Drug Interaction Handbook | Herr SM. | Church St. Books |

| Herb, Nutrient, and Drug Interactions | Stargrove, M. Treasure, J. | Elsevier Mosby |

| The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety | Bone K., Mills S. | Churchill Livingstone |

| Toxicology and Clinical Pharmacology of Herbal Products | Cupp M. | Humana Press |

| Monographs | ||

| American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (AHP) | Upton R. (ed.) | American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, Scotts Valley, CA |

| European Scientific Cooperative of Phytotherapy (ESCOP) | ESCOP | ESCOP |

| World Health Organization (WHO) | World Health Organization | Geneva, Switzerland |

| Websites | ||

| The Cochrane Library | http://www.cochrane.org/ | |

| Health Canada | http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca | |

| The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) | www.nccam.nih.gov | National Institutes of Health |

| Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database | www.naturaldatabase.com | |

| Natural Standard | http://www.naturalstandard.com/* | Elsevier Mosby |

| Natural Standard Herb and Supplemental Handbook: The Clinical Bottom Line | http://naturalstandard.com/* | Elsevier Mosby |

| Natural Standard Herb and Supplement Reference: Evidence–Based Clinical Reviews | http://naturalstandard.com/* | Elsevier Mosby |

| Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) | www.ods.od.nih.gov | National Institutes of Health |

| TOXNET | http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov | National Library of Medicine |

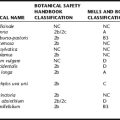

Class 1. Herbs that can be safely consumed when used appropriately.

Class 3. Herbs for which significant data exist to recommend the following labeling:

Class 4. Herbs for which insufficient data are available for classification.

ADVERSE DRUG REACTIONS, HERBAL ADVERSE EVENT REPORTS, AND ADVERSE EVENTS REPORTING SYSTEMS

Several operational definitions exist regarding what constitutes adverse drug reactions (ADRs) of varying severity. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an ADR is defined as “Any response to a drug which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiologic function.”9 For reporting purposes, the FDA categorizes a serious adverse event as one in which “the patient outcome is death, life-threatening (real risk of dying), hospitalization (initial or prolonged), disability (significant, persistent, or permanent), congenital anomaly, or required intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage.”10 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) defines a significant ADR as any unexpected, unintended, undesired, or excessive response to a drug that:

Consistent with this definition, allergic and idiosyncratic reactions are also considered ADRs.11 Not technically classified as ADRs are side effects, which are defined by ASHP as “an expected, well-known reaction resulting in little or no change in patient management (e.g., drowsiness or dry mouth due to administration of certain antihistamines or nausea associated with the use of antineoplastics)” and that has “a predictable frequency and an effect whose intensity and occurrence are related to the size of the dose.” Also not categorized as ADRs are “drug withdrawal, drug-abuse syndromes, accidental poisoning, and drug-overdose complications.”11

Following the thalidomide disaster of the 1950s, WHO established and has maintained an international adverse drug events reporting system. Since 1978, the WHO International Drug Monitoring Program (IDMP) has collected ADR reports from 60 participating nations, and now includes both pharmaceutical and botanical medicine information. Of the more than 2.5 million reports in their International Drug Information System (INTDIS) database, approximately 10,000 relate to herbal medicines, primarily involving multiple ingredients.12 This demonstrates a remarkably low incidence of serious ADRs resulting from herbal products, especially when compared with that of pharmaceutical drugs and the much larger worldwide consumption of botanicals compared with conventional medications. Many of the reports were associated with negative interactions with conventional medications and most side effects were reported for people 60 to 69 years of age.

A retrospective review of adverse effects reports (AERs) due to herbal medicines made to the National Poisons Unit of the United Kingdom was conducted in 1991. Between 1983 and 1989 a total of 1070 inquiries were made. Twenty-five percent of reports were of subjects with acute symptoms. Most confirmed adverse events were due to herbal sedatives.13 Ernst conducted a survey of complementary and alternative medicine users in the United Kingdom. Of those who had reported use of herbal medicines, 8% reported having observed adverse effects, none of which were considered serious.13

Adverse events associated with dietary supplements are not effectively monitored in the United States.14 The main AER systems are local and national poison control centers and the FDA’s MedWatch program, all of which have serious limitations. Most reporting systems, including these, are passive systems with no criteria for submission, no verification of the authenticity or accuracy of reports, and no effective follow-up or investigation. In order to be meaningful, AERs must be critically reviewed and products analyzed. Yet, neither a systematic review of the patient or event is conducted, nor is the product involved in an event typically analyzed, making it impossible to establish a causal relationship between an event and an herb/herbal product. Further, recording practices are highly variable between systems and between centers within the same reporting system and there is often selection bias.14

A relatively recent survey of data from US poison control centers evaluated the incidence of AERs for all dietary supplements.14 In a 10-month period, 1466 reports of potential events due to ingestion of supplements were made. More than one-third of these (534) were unintentional ingestions; 471 reported no symptoms. Half (741) of the total reports produced symptoms. The reviewers reported that 66% (489) were associated with dietary supplement exposure with varying degrees of confidence and 27% (132) were considered to be either definitely or probably related, whereas 34% (166) were reported as definitely or probably unrelated. The balance of reports (39%; 190) represented a 50% chance for the event to be correlated to supplement use. Ninety of the subjects used supplements in an attempted suicide, whereas the others used supplements for various reasons, ranging from the treatment of specific conditions (35%) to enhanced athletic performance (10%) and dieting (14%), among others. Botanicals most frequently associated with adverse events included ma huang (Ephedra sinensis), St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), guarana (Paullinia cupana), and ginseng (species not identified). Of a total of 401 calls specifically related to adverse events of dietary supplements, 286 events were classified as mild, 89 as moderate, and 22 as severe, with a total of four deaths. Subjects experiencing symptoms were taking as many as 44 ingredients concurrently and had more serious adverse events than did those taking fewer supplements long-term. However, 89% of these adverse events were considered mild (57%) or moderate (32%); 11% were reported as severe or resulted in death. Most acute reports (95%) were considered mild (77%) or moderate (18%), and 4% severe or death. Many of these reports suffer from the same limitations of not being subjected to critical review or product characterization. Of all the supplement adverse events reported, only 12 products were retrieved for analysis. In comparison, a total of 61,229 calls regarding adverse events due to other consumed substances, mostly pharmaceuticals, were made in the same time period.

CATEGORIES OF COMMON HERBAL ADVERSE EFFECTS

The Toxicologic Medical Unit of Guy’s and St. Thomas Hospital in London conducted a 5-year toxicologic review of adverse events caused by herbal drugs based on reports made to the National Poison Control Center.15 Drowsiness and dizziness followed by vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea were the most commonly reported side effects. Other events of note included agitation and irritability, cardiac arrhythmias, psychological disturbances, and facial flushing. Interaction of botanical and conventional anticoagulants has resulted in reports of abnormal bleeding, and effects of interactions with herbs that rely on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system have resulted in elevations or decreases in serum drug concentrations affecting clearance times, efficacy, and toxicity. Reports of liver abnormalities were most commonly associated with Chinese herbal medicines.

Allergic and Idiosyncratic Reactions

An allergic reaction is defined as an immunologic hypersensitivity, occurring as the result of unusual sensitivity to a drug.11 Allergic reactions occur via immune-mediated mechanisms, for example, the development of drug-specific antibodies, reactions to drug–antibody complexes, or release of inflammatory compounds. They are largely unpredictable and can range from minor complaints such as itchy eyes, runny nose, and minor skin reactions, to fatal anaphylactic shock. Allergic reactions to herbal medicines are uncommon, but may result from a compound inherent to the plant, or from contamination of the plant with molds, fungi, or other agents. Patients with known sensitivity to specific allergens, for example, members of the Asteraceae family, should use herbs in this family with caution or avoid them altogether. Plants in this family are rich in sesquiterpene lactones, a constituent with known allergenicity, and primarily responsible for allergic reactions; however, any plant may cause a reaction in any individual.16

An idiosyncratic reaction is defined as an abnormal susceptibility to a drug peculiar to the individual.11 Idiosyncratic drug reactions (IDRs) are also immune mediated, and may result in severe skin reactions, anaphylaxis, blood dyscrasias, hepatotoxicity, and internal organ involvement. Symptoms such as fever and joint pain may accompany an IDR. The immune involvement appears to be a result of the interaction of cellular proteins with reactive drug metabolites, and thus differs slightly from the etiology of allergic reactions. These types of reactions occur very infrequently, are independent of dose, and are highly unpredictable. Risk factors for idiosyncratic reactions include increasing age, concurrent use of multiple medications (polypharmacy), hepatic disease, renal disease, malnutrition and/or decreased body weight, chronic alcohol consumption, and gender (women are more susceptible to IDRs). Specific enzyme deficiencies may be involved in some IDRs. Hepatotoxicity reactions reported with use of kava kava (Piper methysticum) are most likely a result of idiosyncratic reaction to this herb.16

Skin reactions, such as contact dermatitis, irritation, and burns are the most common types of allergic reaction to herbs, and are associated with the topical application of irritating herbs or repeated exposure through handling of herbs, such as among employees in the herbal manufacturing industry. Asthma is also known to occur as a result of repeated exposure in this latter population. Care must therefore be taken when applying external therapies and also with repeated exposure to herbs and dust from herbs. Reports of contact dermatitis, allergic reaction, or other skin irritation are especially common with garlic (Allium sativum), mustard powder, cayenne pepper (Capsicum annum), and members of the Asteraceae family. Oral administration of the following herbs has also been associated with general skin reaction: echinacea (Echinacea spp.), goldenrod (Solidago virgaurea), and kava.16

Adverse Reactions Caused by Overdose

There are a number of reported incidences of overdose with herbal products, including unintentional overdose, as well as suicide attempts, most of which have failed.17 There is little information regarding the treatment of overdose of herbal products. As with all pharmacologic agents, treatment should be based on the herb’s mechanisms of action and the reaction.

Reactions Due to Specific Herbs and Toxic Compounds in Plants

Ephedra (Ma Huang)

Ma huang has been used in Chinese herbal medicine since at least the first century, primarily for acute conditions of the upper respiratory system. TCM practitioners and Western herbalists have used this herb with a high degree of safety. Pharmacologically, it is an adrenomimetic, mimicking the effects of epinephrine, eliciting a central nervous stimulating effect and accompanying thermogenic and appetite suppressant effects; thus, it is used in weight loss and “energy-enhancing” products. Both of these categories are subject to overuse and abuse for those seeking quick weight loss solutions and enhanced athletic performance. However, because the mechanism is one of putting the body into an artificial state of induced stress, the use of ephedra for both indications is counter to principles of most natural health care providers. In actuality, a review of the adverse events collected by FDA show that adverse events caused by the botanical itself are rare and even perhaps nonexistent. Rather, ephedra-related adverse effects have been alleged for products that contain concentrated amounts of ephedrine, usually in combination with high concentrations of caffeine. The most common side effects are nervous irritability, anxiety, heart palpitations, and hypertension. Although in most subjects these are minor and reversible upon discontinuation of the preparation, in some they have been associated with significant adverse effects and reportedly even fatal outcomes. Unfortunately, the ban on all ephedra products has led to a prohibition against the legitimate and appropriate use of the crude herb ma huang by herbal practitioners.

Kava Kava (Piper methysticum)

Nevertheless, based on these reports several countries have adopted restrictions on kava sales. For example, in Australia, kava products must be prepared as aqueous (nonalcohol) solutions of whole or peeled rhizome, and must not contain a recommended daily dose of more than 250 mg of kava lactones; tablets or capsules must not exceed 125 mg/tablet; tea bags must not exceed 3 g/tea bag. If a product contains more than 25 mg/dose, then appropriate warning labels must accompany the product. In the United Kingdom, legislation was enacted as of 2002 to prohibit the sale of foods containing kava, and herbal products were limited to 625 mg/dose. In June 2002, Germany banned the therapeutic use of kava completely.16 A review was conducted by the FDA. Due to the lack of compelling data about a causal relationship, no ban was imposed in the United States. However, fear of potential litigation has caused product liability insurance carriers to deny coverage for kava products, ostensibly eliminating widespread availability of kava. Such events have to be juxtaposed against prevalence of use. In Europe alone, more than 100 million daily doses are used. The Swiss regulatory agency in charge of the control of medicines reported the following: “It is estimated that 8 cases of hepatotoxicity have occurred in a total of 40 million daily doses or 1 case per 170,000 courses of treatments of 30-days duration.”18 The normal incidence of hepatotoxicity in the population at large is 10 in 10,000. This suggests that hepatotoxic events of kava are much less than what is normally observed in the population at large. For a thorough review of kava safety, see The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety.

Toxic Plants Not Typically Used

Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids

The unsaturated form of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) found in a number of commonly used medicinal plants, for example, comfrey (Symphytum officinale), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), or plants in the genus Senecio, can directly cause veno-occlusive disease (VOD) and have resulted in fatalities, usually when consumed as a survival food during times of drought or famine or when used medicinally over a prolonged period of time or in susceptible individuals. Because a number of botanicals used medicinally contain toxic PAs, and because some herb references continue to recommend such botanicals, caution is warranted (Box 4-1). Not all forms of PAs, such as the saturated PAs found in Echinacea species, are converted to toxic pyrroles, and therefore plants containing nontoxic PAs (saturated) should be distinguished from those that are toxic.16

Aristolochic Acids

Aristolochic acid (AA), even in small amounts, can cause both stomach and kidney cancer.19 A ban on AA-containing plants (Table 4-2) has been implemented in many countries, and the FDA issued a consumer advisory in 2001 warning the public about this problem. However, many products that may contain AA remain on the market in Asia. Domestically, plants that may be confused with AA-containing plants have been subjected to systematic analysis at the point of importation before they are allowed in commerce. Herbal practitioners must be vigilant about herbal and supplement products that may be mixed with AA-containing plants and ensure that manufactured products prescribed have the necessary controls to avoid adulterants.

TABLE 4-2 Botanicals Containing Aristolochic Acids (AAs) or Those That May Be Mixed with AA-Containing Plants

| AA-CONTAINING PLANTS | POSSIBLE SUBSTITUTIONS* |

|---|---|

* These botanicals do not contain AA. It is recommended that these botanicals be subjected to AA testing to prevent adulteration. For a more complete listing see: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/ds-bot2.html

Botanical Quality Standards and Reactions Caused by Contamination and Adulteration of Herbs

The safety of any medicinal product is partly dependent on the manner in which the product is produced. Although individuals, organizations, industry, and government are actively working to establish national quality control (QC) standards, current standards are not a guarantee for herbal products in the United States, or those imported from countries such as China and India. European herbal product standards are generally stricter than most other countries, including the United States; thus, European herbal products have a greater likelihood of safety and quality. The most important aspects of QC include the accurate identification, relative purity, and relative quality of raw material used in herbal products (Tables 4-3 and 4-4).

TABLE 4-3 Potential Toxic Plant Adulterations Causing Safety Concerns

| BOTANICAL NOMENCLATURE | POTENTIAL ADULTERANT | POTENTIAL ADVERSE EVENT |

|---|---|---|

| Black cohosh | Other species of cohosh | Some species of cohosh are toxic |

| Echinacea purpurea and others species | Missouri snakeroot | Allergic reaction in sensitive individuals |

| Siberian ginseng (eleuthera) | Chinese silk vine | Birth defects if used in pregnancy |

| Skullcap | Germander | Hepatotoxicity |

| Chinese star anise | Japanese star anise | Convulsions |

| Stephania | Aristolochia fang ji | Nephrotoxicity, cancer |

TABLE 4-4 Potential Contaminants of Herbal Products

| ADULTERATING AGENT | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Botanicals | Aristolochic acid-containing plants, belladonna, Chinese silk vine, digitalis, germander, Japanese star anise, non-medicinal plant parts |

| Filth | Dirt, insect fragments |

| Microorganisms* | Toxic strains of E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, salmonella, shigella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Microbial toxins | Aflatoxins, bacterial endotoxins |

| Pesticides** | Chlorinated pesticides (DDT, DDE, aldrin, dieldrin), fungicides, herbicides |

| Sterilization Agents† | Ethylene oxide, methyl bromide, phosphine, gamma-irradiation |

| Heavy metals‡ | Arsenic, cadmium, lead, mercury |

| Conventional Drugs§ | Analgesics, anticoagulants, anti-inflammatories, benzodiazepines corticosteroids, hormones |

* Current law prohibits the presence of toxic microorganisms in herbal products. Contaminated products can be removed from the market. To date, there have been no published reports of herbal products toxicity from such microorganisms.

** Although some of these pesticides have been banned in the United States for decades, they may still be in use in other countries. Conversely, some pesticides may be approved for use in common foods but lack approval for use on herbal products.

† These sterilization processes, although approved for use in certain foods, are not approved for use on herbal products.

‡ Heavy metals in food and water is a problem worldwide but have been specifically noted to occur in numerous herbal medicine products manufactured in China.

§ It is prohibited to combine conventional drugs in products marketed as dietary supplements.

Most herbs and botanical products are not tested before importation into the United States. It is impossible for consumers and health professionals to determine if such contaminations are present without subjecting the product to extensive testing. Again, any presence of a known pathogen (e.g., Escherichia coliform) or prohibited treatment (certain pesticides or gamma irradiation) renders a product adulterated and subject to removal from the market by the FDA. However, regulatory oversight in this area is almost nonexistent. The best way for practitioners to avoid potentially contaminated or adulterated products is to become knowledgeable of the practices of suppliers and manufacturers, and identify those with high quality standards (see Identifying Quality Botanical Medicine Products). Companies that are run by or employ qualified herbalists on their staff and that serve the needs of health professionals are often the most reliable, but this in itself is not a guarantee of quality.20

Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicines Mixed with Conventional Pharmaceutical Drugs

It is not uncommon for Chinese herbal products made in Asia, including those sold in the United States, to be adulterated with conventional pharmaceutical drugs.21 Adulterants have included caffeine, paracetamol, indomethacin, hydrochlorothiazide, prednisolone, barbiturates, and corticosteroids.22 The purpose for the inclusion of pharmaceutical drugs in botanical products is presumed increased efficacy. However, inclusion of such substances is not consistent with principles of traditional Chinese medicines. In a survey evaluating herbal products used in hospitals in Taiwan, approximately 24% of 2406 herbal drugs tested contained pharmaceuticals.

Significantly, in most cases the pharmaceutical adulterants are not disclosed on the product label or packaging. Herbal products adulterated with conventional medications have been found to be manufactured in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.21 In the United States, under dietary supplement regulations, such products are considered to be adulterated and are subject to removal from the market. Thus far, there have been no reports of the addition of pharmaceuticals in domestically made Chinese herbal products. Although there are undoubtedly high-quality herbal products manufactured in Asia, it is currently almost impossible for consumers and most health professionals (even trained TCM practitioners) to differentiate between adulterated and nonadulterated products. Thus, patients using some traditional Chinese herbal medicine products in combination with conventional medications may be also be unknowingly subjected to unexpected drug–drug interactions via a pharmaceutical adulterant.

Ayurvedic Herbs and Heavy Metal Contamination

In a study conducted by Saper et al., it was found that one of five Ayurvedic herbal products produced in South Asia and sold in Boston-area South Asian grocery stores contained potentially harmful levels of lead, mercury, and/or arsenic. If taken as recommended by the manufacturers, 20% of products could result in heavy metal intakes above published regulatory standards.23 The products selected, however, were not necessarily representative of typical Ayurvedic products, as most included heavy metals as ingredients, whereas the majority of Ayurvedic herbal products do not. The Indian government has recently made testing for heavy metals compulsory and labeling for heavy metals within permissible limits mandatory for Ayurvedic medicine products produced in India and destined for export beginning January 1, 2006, as part of an attempt to address this problem.24

HERB–DRUG INTERACTIONS

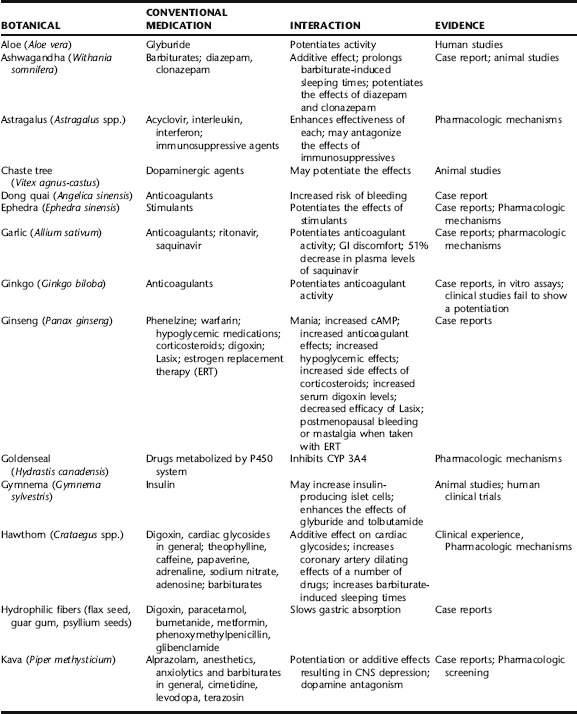

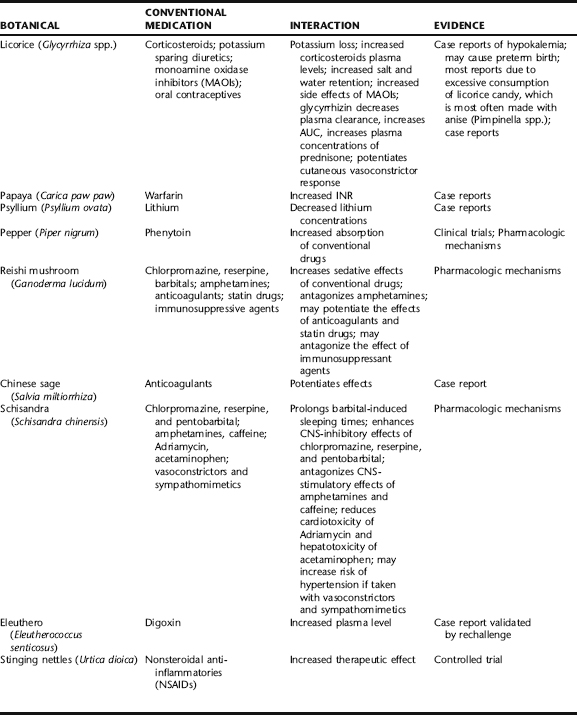

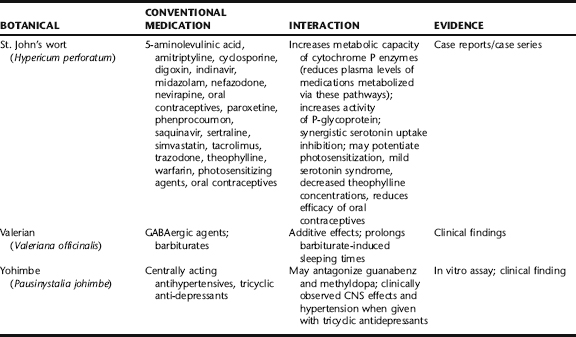

Herb–drug interactions are the most prevalent source of reported adverse effects worldwide and warrant serious concern. According to a 1998 report by Eisenberg et al., 61.5% of patients who used nonconventional therapies did not disclose this to their physicians.25 In another survey, conducted among patients at the Mayo Clinic, even though patients were asked about supplement use in a written intake form, approximately half did not disclose this until engaged in a structured interview.26 The same subjects similarly did not report on their prevalence of OTC medication use. These findings suggest that health professionals must be proactive in garnering information about both supplement and OTC drug use. Herbs and pharmaceutical drugs can interact either predictably or unpredictably with both positive and negative results (Table 4-5). Such modulation may be due to direct pharmacologic activity or may lead to changes in the P450 enzyme system that affects drug absorption or clearance. For orally consumed medications, hydrophilic fibers and demulcents can interfere with absorption of conventional drugs, thereby decreasing their efficacy, whereas certain spices (e.g., black pepper, ginger) may increase drug absorption. Many botanical types of tannin (e.g., white oak bark, witch hazel) are capable of binding to both alkaloid and mineral drugs resulting in decreased absorption of these. (See Appendix 3 for a comprehensive table of potential herb–drug interactions for common herbs.) The Botanical Safety Handbook (CRC Press) provides a list of botanicals known to interact with conventional medications.

Reports of Interactions

The literature consists mainly of case reports and pharmacologic data that have not been assessed for clinical relevance.27 Patients or physicians make most individual case reports, usually after having experienced or observed an unexpected adverse reaction. Case reports, which typically are not subjected to critical review, are among the most unreliable body of information from an evidence-based perspective. There have been a few critical reviews that provide some meaningful guidance regarding herb–drug interactions (Box 4-2). Researchers Izzo and Ernst conducted a systematic review of herb–drug interactions of seven of the most popularly used botanicals: garlic, ginkgo, St. John’s wort, saw palmetto, kava kava, Asian ginseng, and echinacea. Clinical data were collected from standard databases, recent articles and books, and interviews with herbal product manufacturers,10 herbal experts,8 and organizations related to medical herbalism.24 In a 21-year period (1979–2000), a total of 41 case reports or case series in 23 publications and 17 clinical trials were obtained. Of these, only 12 interactions could be considered life threatening (mostly associated with a dangerous reduction in blood plasma levels of cyclosporine in organ transplant patients using St. John’s wort) owing to a putative effect on cytochrome P450 systems.28

The paucity of incidences of herb–drug interactions for these seven botanicals should also be viewed within the context of their total use. Definitive data regarding actual herb use are lacking, but available published marketing reports for ginkgo, kava, and St. John’s wort provide some guidance. Ginkgo is by far the most widely used and prescribed medicinal herb in the world. According to a review of DeFeudis, from 1979 to 1998, approximately 110 million daily doses of ginkgo leaf extract were sold in France alone. According to market data of Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH, the makers and world’s leading marketer of the most clinically tested ginkgo extract (EGb 761), in the period from 1979 to 1997, it was estimated that more than 2 billion daily doses of ginkgo extract were distributed worldwide. A more recent report estimates that from 1997 to 2002, 1.375 billion daily treatments of ginkgo single preparations have been administered in Germany alone. Up until 2003, a total of only four case reports of potential interactions between ginkgo and conventional medications had been published.29 Two of these were associated with bleeding events. This has led to significant concerns raised regarding its potential to increase the effects of anticoagulants. However, such events, if causal, are rare. More than 40 clinical trials with several thousand subjects have been conducted using the EGb 761 ginkgo extract with no reports of increased bleeding. A number of studies have specifically looked at its potential for increasing the anticoagulant effects of aspirin and warfarin with mostly negative results; it has been included in pharmacovigilance reviews throughout Europe for decades. Nonetheless even in cases in which an interaction has not been definitively confirmed, caution should be advised.

As of 2001, St. John’s wort was the primary antidepressant used throughout Europe with approximately 66 million daily doses in Germany, outselling most conventional antidepressants. Up until the 2000 review of Izzo and Ernst, a total of 29 potential interactions were reported. Most of those were associated with decreased blood cyclosporine levels due to enhanced hepatic enzyme induction (cytochrome P450). Others were associated with an additive effect of St. John’s wort wi selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Again, considering the prevalence of St. John’s wort use, such incidences of adverse effects are rare. With increased understanding that St. John’s wort does affect P450 enzyme systems, such interactions can be more readily predicted and therefore minimized (see Drugs Metabolized via Cytochrome P450 System).28

Categories of Herb–Drug Interactions

Anticoagulants

According to case reports, ginkgo and garlic are among the botanicals most widely reported as interacting with anticoagulants. For ginkgo, there are at least two case reports of interactions, one each with aspirin and warfarin.30,31 In neither case could an association be definitively determined. However, upon cessation of ginkgo, bleeding times returned to baseline norms. An anticoagulant effect of ginkgo is partially supported by the presence of ginkgolide B, which exhibits in vitro inhibition of platelet activating factor. However, the amount of ginkgolide B in ginkgo extract is very small and is unlikely to contribute to this activity in a significant clinical way. There have been a number of other case reports suggesting an association between bleeding events and use of ginkgo. Conversely, ginkgo has also been one of the most researched botanicals and subject of numerous meta-analyses and evidence-based reviews. None of the formal trials have noted any bleeding problems. Some of these have specifically investigated the effects of ginkgo in conjunction with anticoagulants with negative findings.29 Ginkgo extract is one of the most widely prescribed and broadly used of all approved botanical drugs worldwide. The scarcity of reports relative to its widespread supervised and unsupervised use suggests that bleeding is not a common problem, although caution is advised.

Garlic has been reported to thin the blood by at least three different mechanisms; fibrinolytic activity, inhibition of platelet aggregation, and decreased fibrinogen activity. Most of these findings were from human studies with very small patient populations.32 Consumption of garlic as a food has not been implicated in bleeding events, suggesting that cooked garlic, which is most commonly consumed, does not contain the compounds responsible for the anticoagulant effects. This is likely as numerous studies suggest that allicin, which is lost in cooking, is associated with its putative anticoagulant activity. Thus, varying preparations may elicit different actions, depending upon the constituents present in the preparation. Primarily, supplemental forms of garlic preparations, especially those delivering allicin, should not be used, or should be used very cautiously in those with bleeding problems, using anticoagulants or prior to surgery.

Other botanicals that have been reported to potentiate the effects of anticoagulants include those that inhibit platelet aggregation through an inhibition of thromboxane synthetase (e.g., ginger), arachidonic acid (e.g., those rich in essential fatty acids), or epinephrine (e.g., garlic). A number of Chinese herbs have been implicated in bleeding problems. Most notably these include Chinese salvia (Salvia miltiorrhiza), dong quai (Angelica sinensis), and corydalis (Corydalis yanhusuo). These botanicals are classified as possessing blood thinning properties from a traditional Chinese medical perspective and so such an effect is predictable. In the case of dong quai, which is commonly used in the treatment of gynecological conditions and anemia, a 46-year-old woman experienced a greater than twofold elevation in prothrombin time (from 16.2 to 27 seconds) and International Normalized Ratio (INR) (from 2.3 to 4.9) after consumption of a commercial dong quai product. No other cause for the increase could be determined and coagulation values returned to acceptable levels within 1 month after discontinuing dong quai.33 Similar increases in INR have been reported for Chinese salvia, one of the most commonly used botanicals in Chinese medicine for increasing blood circulation. Conversely, high doses of green tea (Camellia spp.), as well as ginseng, have been reported to decrease the effects of warfarin.34,35

A relatively large number of medicinal plants can potentially interact with conventional anticoagulant medications. Therefore, monitoring of bleeding signs and INR is warranted when using botanicals with known effects on bleeding mechanisms or those with a history of use in altering circulation. These same botanicals should also be avoided immediately prior to surgery (Table 4-6).

TABLE 4-6 Botanicals Best Avoided Prior to Surgery or with Anticoagulants

| BOTANICAL | ACTION |

|---|---|

| Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) | Potential anticoagulant effect if the material was subjected to fermentation; potential coagulant activity due to vitamin K content |

| Angelica (Angelica spp.) | Possible anticoagulant effects |

| Asafoetida (Ferula foetida) | In vivo anticoagulation |

| Borage seed oil (Borago officinalis) | Possible anticoagulant effects of gamma linolenic acid (GLA) |

| Black currant seed oil (Ribes nigrum) | Possible anticoagulant effects of gamma linolenic acid (GLA) |

| Cayenne pepper (Capsicum annum) | Antiplatelet aggregation due to capsaicin |

| Chamomile flowers (Matricaria chamomilla) | Potential anticoagulant effect |

| Chinese salvia root (Saliva miltiorrhiza) | Anticoagulant effect |

| Chinese skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis) | Inhibits vitamin K reductase |

| Cornsilk (Zea mays) | Contains vitamin K |

| Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) | Possible anticoagulant effects |

| Evening primrose seed oil (Oenothera biennis) | Possible anticoagulant effects of gamma linolenic acid (GLA) |

| Fenugreek seed (Trigonella foenum) | Anticoagulant effect |

| Feverfew leaf (Tanacetum parthenium) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Garlic bulb (Allium sativum) | Anticoagulant effect; can interact with warfarin |

| Ginger root (Zingiberis officinalis) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Ginkgo leaf (Ginkgo biloba) | Potential anticoagulant effect |

| Ginseng root (Panax ginseng) | May exacerbate hypertension; inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Horse chestnut seed (Aesculus hippocastanum) | Potential anticoagulant effect due to saponin compounds (esculetin, osthole) |

| Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza spp.) | Potential anticoagulant effect |

| Papain (from papaya) | Potential for increased bleeding |

| Parsley leaf (Petroselinum crispum) | Contains vitamin K |

| Pau D’Arco (Tabebuia spp.) | Potential anticoagulant effect due to lapachol, which works similarly to warfarin |

| Red clover blossoms (Trifolium repens) | Potential anticoagulant effect |

| Shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | Contains vitamin K |

| St. John’s wort herb (Hypericum perforatum) | Prolongs effects of anesthesia |

| Stinging nettles leaf (Urtica dioica) | Contains vitamin K |

| Turmeric root (Curcuma longa) | Potential anticoagulant effect |

Anesthetics, Anticonvulsants, Barbiturates, Benzodiazepines, Opioids, Sedatives

Hundreds of plants have been used historically for their sedative, pain killing, and anticonvulsant activity. Used in combination with similarly acting medications enhancement of activity resulting in loss of muscular coordination or a prolongation of anesthesia- or barbiturate-induced sleeping times has been observed. Compounds in valerian root, for example, display an affinity for barbiturate, GABA-A, peripheral benzodiazepine, serotonin, and opioid receptors, whereas California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) contains the alkaloid chelerythrine, which is a protein kinase inhibitor (Table 4-7).

| BOTANICAL | INTERACTING MEDICATIONS | POSSIBLE EFFECT |

|---|---|---|

| Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) | Barbiturates | Potentiation |

| Black currant seed oil | Anticonvulsants | May decrease seizure threshold |

| Borage seed oil | Anticonvulsants | May decrease seizure threshold |

| California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) | Analgesics, sedatives | Potentiation |

| Catnip (Nepeta cataria) | Barbiturates | Potentiation |

| Chamomile (Anthemis nobilis) | Barbiturates | Potentiation |

| Cramp bark (Viburnum opulus) | Anticonvulsants | Contains salicylates, may increase effect |

| Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus) | Barbiturates | Potentiation |

| Evening primrose (Oenothera biensis) | Anticonvulsants | May decrease seizure threshold |

| Hops (Humulus lupulus) | Sedatives | Potentiation |

| Kava kava (Piper methysticum) | Anesthetics, barbiturates | Prolonged sedation times |

| Passion flower (Passiflora incarnata) | Barbiturates | Potentiation |

| Schizandra (Schisandra chinensis) | Barbiturates | Potentiation |

| St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) | Anesthetics, benzodiazepines | Prolonged anesthesia times; decreased efficacy in some cases, increased effects in others; binds to GABA receptor |

| Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) | Anesthetics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines | Prolonged sedation times; binds to multiple neurologic receptors |

| Willow (Salix spp.) | Anticonvulsants | Contains salicylates, may increase effect |

| Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) | Anticonvulsants | Contains salicylates, may increase effect |

Cardiovascular Medications

Cholesterolemic drugs, such as the statins, inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis through an inhibition of HMG-coenzyme reductase. Any botanical that has a cholesterol lowering effect through the same pathway may result in potentiation. The primary botanicals used by American consumers for reducing cholesterol levels include red yeast (contains lovastatin, which acts similarly to statin drugs), garlic, and gum guggul resin. Although this potential interaction is not life threatening, it may require modifying the dose of conventional medications. Other classes of botanicals, such as laxatives, may indirectly negatively interact with cardiovascular medications by causing potassium loss (Table 4-8).

TABLE 4-8 Botanicals That May Interact with Cardiovascular Medications

| THERAPEUTIC CATEGORY | BOTANICAL | EFFECT |

|---|---|---|

| Antiarrhythmics | Digitalis*, lily of the valley, squill | All contain cardiac glycosides |

| Anticoagulants | See Table 4-5 | |

| Antihypertensives | Digitalis, garlic, hawthorn, lily of the valley, squill | |

| Calcium channel blockers | Coltsfoot | |

| Cardiac glycosides | Digitalis, figwort, lily of the valley, squill; eleuthera; hawthorn | Some contain cardiac glycosides; eleuthera can increase plasma digoxin levels; hawthorn is positively inotropic |

| Cholesterolemic agents | Artichoke, fenugreek, garlic, ginger, guggul, red rice yeast | Increased therapeutic effect; red rice yeast contains lovastatin |

| Diuretics | Agrimony, arjuna, birch leaves, celery seed, corn silk tassels, couch grass, goldenrod, horsetail, juniper berry, phyllanthus, Rehmannia | Increased potassium loss |

* Digitalis is not available as a botanical dietary supplement and is rarely prescribed by medical herbalists.

Drugs Metabolized via Cytochrome P450 System

Several botanicals have demonstrated a relatively strong in vitro effect on CYP450 3A4 (CYP3A4), including St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa), echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), and licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra).36 However, in vitro data may not accurately reflect what occurs in humans. Most cytochrome P450 effects that are reported are due to negative observations derived from case reports or from in vitro data that may have no clinical relevance. In a few of the most noted cases, St. John’s wort, was shown to inhibit CYP3A4 in vitro and stimulate it in vivo. According to case reports, two transplant patients were medicated with cyclosporine to prevent organ rejection. After self-medicating with St. John’s wort, cyclosporine plasma levels were found to be 25% to 50% lower than expected resulting in acute organ rejection in one of the subjects. Upon discontinuation of the botanical, drug plasma levels returned to expected levels. Other such case reports have been made suggesting strongly that St. John’s wort and other botanicals that upregulate the cytochrome P450 system must not be used in conjunction with immunosuppressant drugs in organ transplant patients (see http://medicine.iupui.edu/flockhart/table.htm for a regularly updated resource on substances that interact with the cytochrome system).37

Hypoglycemic Agents

There is very little data regarding the effects of botanicals on insulin-dependent diabetes. Some botanicals are reported to have an effect directly on insulin production and islet cells, others modify glucose levels through decreased glucose absorption, and others may have an effect on insulin resistance. There are no definitive data on the appropriate use of antidiabetic botanicals in the treatment of diabetes. High fiber intake can inhibit glucose absorption as can consumption of mucilaginous herbs. Use of such herbs in conjunction with hypoglycemic therapies can potentially result in decreased glucose absorption that can alter insulin needs. Some antidiabetic medications such as glibenclamide specifically have been reported to be affected by the use of high fiber botanicals such as konjac mannan (Amorphophallus konjac), a once popular weight loss supplement (Box 4-3).

Immune Suppressants and Immune-Enhancing Therapies

Many botanicals possess immunomodulatory activity. Some of these, such as echinacea, are used for the prevention or reduction of severity of colds and flu. Others, such as astragalus and Reishi mushrooms, are used for general immune enhancement or specifically in conjunction with conventional cancer therapies. Prudence dictates that such herbs should not be used in conjunction with immunosuppressant therapies such as those used in organ transplant patients or in those with autoimmune disease. There are case reports of Echinacea exacerbating symptoms of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. There are very little data regarding the use of botanicals with immunosuppressive therapies (Box 4-4). No well-designed trials regarding such combined therapies are available. There are limited data suggesting a positive effect of these when used in conjunction with conventional therapies. 38 39 40 Many integrated health care professionals use such botanicals to reduce side effects of conventional therapies and minimize the risk of contracting opportunistic infections. Currently, the available evidence regarding the usefulness of natural therapies appears to be stronger for improvement of symptoms than it is for slowing of disease progression.41 The use of immune modulating botanicals must be weighed against the cytotoxic therapies of Western medicine.

Diuretics

Pharmacologic evidence regarding definite diuretic activity of many botanicals is lacking, yet they are very commonly used. In general, use of diuretics can lead to potassium loss, which can potentially lead to fatal arrhythmias. This does not appear to have been reported with use of herbal diuretics. There are, however, some reports of potassium loss through the excessive use of purging cathartics as part of weight loss programs, some that also contain diuretics. Part of the reason may be that many herbal diuretics, for example dandelion leaf (Taraxacum officinale), also contain high amounts of potassium, which may actually result in increased in serum potassium levels (Box 4-5). Nonetheless, care should be taken when using diuretics with patients on medications that have narrow therapeutic windows, or when potassium depletion may place the patient at risk.

Tannins and Iron Availability

Botanicals rich in tannins, a common constituent of many barks and leaves, can decrease the absorption of certain classes of drugs, most notably alkaloidal and mineral drugs such as colchicine, ephedrine, copper, iron, and zinc; thus, individuals with specific deficiencies (e.g., iron, zinc) may be advised to avoid tannin-rich botanicals for the duration of supplementation (Box 4-6).

TIMING OF HERB USE

Use of Herbs Prior to Surgery

A number of botanicals should be avoided, or used with care, prior to or when undergoing surgery, largely due to theoretical or known risks of interactions with coagulation therapies or anesthesia. Patients must also be queried regarding their use of botanicals at this time. As noted, there are a number of botanicals with blood-thinning potential, such as ginkgo, garlic, dong quai, and red clover, whose use is so common that patients might not report these in a standard medical history intake. There are also botanicals that have been reported to interact with general anesthesia, most notably, St. John’s wort, which may intensify or prolong the effects of anesthesia. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (http://www.asahq.org/patientEducation/herbal.htm) recommends that patients stop taking herbal supplements 2 to 3 weeks prior to surgery because they may affect anesthesia and bleeding times, and cause dangerous fluctuations in blood pressure. If there is not enough time prior to surgery to stop, patients are recommended to bring the products to their primary care physician so an assessment of any danger can be made.

Use of Herbs in Pregnancy and Lactation

There are many conditions associated with pregnancy for which expectant mothers seek natural therapies, sometimes in the hopes of avoiding what they perceive to be more toxic conventional medications. Such conditions include morning sickness, threatened miscarriage, vaginal infections, anemia, varicose veins, hemorrhoids, depression, anxiety, and sleeplessness. One survey of emergency room visits reported that 14.5% of women used herbal remedies during pregnancy.42 In addition to unsupervised herb use by consumers, approximately 50% of midwives and naturopathic physicians routinely prescribe herbal medicines during pregnancy, including a prominent use of botanicals such as black and blue cohosh (Actaea racemosa, Caulophyllum thalictroides), castor oil (Ricinus communis), and evening primrose oil (Oenethera biensis) for inducing labor. Considering whether to use an herbal medicine during pregnancy requires skill and sound judgment on the part of the practitioner, or in the case of self-medication, careful consideration on the part of the consuming woman. Minimally, the relative health of the expectant mother, the indication, and the appropriateness or inappropriateness of other medications or therapies must be considered. Ultimately, with herbal medicines, the choice of medications should be made by the expectant mother with full knowledge of the potential consequences. There are also significant legal liabilities that are incurred when using herbs in pregnancy. A list of botanicals that should not be used in pregnancy except under the care of a qualified health care professional is provided in Chapter 12, where the special considerations of herb safety during pregnancy are extensively addressed in Chapter 12.

THE RELATIVE SAFETY OF CONVENTIONAL DRUGS AND HERBAL MEDICINES: KEEPING IT ALL IN PERSPECTIVE

When assessing the safety of herbal medicines, it is important to remain cognizant of the relative risks associated with approved medications, used singly and in combination with other agents. It is a common misconception that because a medication is FDA approved it is safe when used as indicated. However, in 1990, the United States General Accounting Office (GAO) reviewed 198 FDA-approved drugs and reported that of these, approximately 102 (51.5%) had serious post-approval side effects. These included anaphylaxis, cardiac failure, hepatic and renal failure, birth defects, blindness, and death.43 At the time of the report, all but two of the medications remained on the market. One study reported that among 1000 older adult patients admitted to the hospital from the emergency room, 538 were exposed to 1087 drug–drug interactions.44 In a review of hospital surveillance reports of adverse events associated with approved medications, Lazarou et al. reported that 2,216,000 patients experienced serious adverse effects resulting in 60,000 to 140,000 fatalities annually as a result of the correct use of conventional drugs.45 Not included in this figure were deaths due to misuse of medications (i.e., improper prescribing, dosing, combining), accounting for another 200,000 patients annually. These figures make adverse events due to approved conventional medications one of the leading causes of death in the United States, almost as many deaths as are associated with smoking, and more than those related to alcohol, recreational drugs, and firearms. Additionally, adverse events associated with conventional drugs have been reported to be the number one cause of hospital admissions (at a cost of $116 million annually), and once in the hospital, approximately 35% of patients are likely to experience an additional adverse drug reaction. In total, this represents estimated extra health care costs of $77 billion annually.46 With this perspective in mind, it may be advantageous for practitioners to wisely counsel patients about the potential benefits of herbal medicines as a means of reducing the high propensity for adverse events due to conventional medications.

Such a belief is reflected in the experience of numerous integrative medical practitioners, conventionally trained physicians who gain further training in various aspects of natural medicine. According to David Rakel, one leading CAM practitioner, “Although it’s important to be aware of drug–herb interactions, we need to be less concerned about them than about interactions between prescribed drugs. Drug–herb interactions are generally much less severe than drug–drug interactions.”47 Samuel D. Benjamin, Director of the Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Family Medicine at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, stated that, “The overwhelming majority of interactions are not related to the use of herbals. Drug–herb interactions don’t compare to drug–drug interactions. Herbals are less toxic than pharmaceuticals.”47 According to medical researcher Adriane Fugh-Berman, Assistant Clinical Professor of Health Care Sciences at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, drug–drug “interactions kill people every day. What I have been really trying to convey to people…is that drug interactions are much more common and severe than drug–herb interactions. As clinicians we should be alert to both types but take pains to keep drug–herb interactions in context.”47

GUIDELINES FOR PRACTITIONERS

Emergency Room Personnel

Botanicals That Should Only Be Used by Qualified Health Professionals

The majority of botanicals that have remained on the commercial market have persisted because of their relatively high degree of safety when used by consumers without the guidance of a health professional. Most do not present a significant enough health risk to warrant prescription-only status. However, historically, relatively toxic botanicals (e.g., aconite, digitalis, and gelsemium) have been used by medical herbalists. Most of these have not remained in the commercial market as dietary supplements. The use of toxic such herbs should be limited to well-trained medical herbalists.48 Recommendations regarding the use of botanicals that should only be used by skilled individuals can be found in the Botanical Safety Handbook (CRC Press).

CONCLUSION

With the increasing prevalence of the use of herbal products, and the fact that many consumers and patients are using herbal products in conjunction with conventional medications, it is becoming increasingly important for health care providers to be aware of potential adverse effects and interactions. Based on a review of the world’s data, adverse effects caused by herbal medicine are relatively rare. A number of botanicals have compared favorably in clinical trials with conventional medications for the same indications, and a critical review of the literature demonstrates a remarkable safety record. For example, ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) has been shown to be similarly effective to conventional nosotropics and better tolerated; whereas contrary to inaccurate media reporting, St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) has been shown to be equal to or more efficacious than standard antidepressant medications but with approximately half the rate of adverse events. 49 50 51 Another herb, kava kava (Piper methysticum) has demonstrated efficacy equal to many standard anxiolytics, with greater safety than the commonly prescribed benzodiazepines.52

INTEGRATING BOTANICAL MEDICINES INTO CLINICAL PRACTICE: ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND GUIDELINES

Lack of general consensus among health practitioners regarding the safety and efficacy of botanical therapies and their place in conventional medical care leaves many health professionals with the ethical dilemma of whether, and to what extent, to integrate herbal medicines into their practices, how much to support patient use, and the challenge of learning which products are efficacious and safe.53 Practitioners are rightly reluctant to recommend or support botanical medicine use because they are uncertain as to which therapies are beneficial, which are merely harmless, and which are harmful. Most lack adequate training in their use unless specifically trained as herbalists. Unfortunately, lack of knowledge about herbal therapies, or disapproval of them, has been demonstrated to reduce patient disclosure of use to their primary care practitioners. It also prevents practitioners from serving adequately as advisors and advocates for their patients regarding safe and effective herb use, and the avoidance of potential herb–drug interactions.

ADDRESSING ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Jeremy Sugarman, in the JAMA article, Physicians’ Ethical Obligations Regarding Alternative Medicine, suggests that physicians facing ethical dilemmas about integrating CAM into their practices, or at least trying to decide how to address CAM use by patients, consider applying a broad “set of inherent ethical principles of the medical profession: respect for persons, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice” into their decision-making process.54 These principles, well known to physicians, are:

GUIDELINES

Once practitioners have decided that their patients have an ethical right to information on the safe and effective use of botanical therapies, or possibly even botanical products, how are they to advise patients about them? Wayne Jonas suggests that health practitioners follow a simple set of practical rules he calls the “four Ps”: protect, permit, promote, and partner.55 He defines these as follows:

Karen Adams, in Ethical Considerations of Complementary and Alternative Medical Therapies in Conventional Medical Settings, suggests consideration be given to the following: (1) whether evidence supports both safety and efficacy; (2) whether evidence supports safety but is inconclusive about efficacy; (3) whether evidence supports efficacy but is inconclusive about safety; or (4) whether evidence indicates either serious risk or inefficacy.53 She advises the following steps as guidelines:

If evidence supports both safety and efficacy, the physician should recommend the therapy but continue to monitor the patients conventionally. If evidence supports safety but is inconclusive about efficacy, the treatment should be tolerated and monitored for effectiveness. If evidence supports efficacy but is inconclusive about safety, the therapy still could be tolerated and monitored closely for safety. Finally, therapies for which evidence indicates either serious risk or inefficacy obviously should be avoided and patients actively discouraged from pursuing such a course of treatment.53

The risk–benefit analysis shown in Box 4-7 should be considered when there is insufficient evidence for or against a particular treatment.

There are numerous medical practices that were once considered fringe, such as biofeedback, that are now a routine part of conventional medicine. As practitioners gain increased experience and confidence with a modality, and as both clinical and pharmacologic studies are done that continue to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the modality, the less fringe a practice seems. Botanical medicines have always been part of human and medical history; their use should not seem entirely foreign today.

SELECTING AND IDENTIFYING QUALITY HERBAL PRODUCTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF QUALITY BOTANICAL PRODUCTS

Regulations Governing Botanical Products

It is frequently stated that botanical dietary supplement products in the United States are not subject to any regulatory standards. This is far from the truth. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 defines dietary supplements and dietary ingredients, establishes a framework for product safety, outlines guidelines for literature displayed where supplements are sold, provides for use of claims and nutritional support statements, requires ingredient and nutrition labeling, and grants the FDA the authority to establish good manufacturing practice (GMP) regulations beyond those for food, which already apply to this class of goods.56

Dietary supplements must conform to federal regulations that control their manufacture, labeling, and marketing as well as state and local health and business regulations. In addition, all supplement products are required by law to provide certain information about their formulation.57 For those who wish to be informed about regulations governing dietary supplements, visit the FDA website at http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/supplmnt.html. The National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements also provides a wealth of information about dietary supplements at http://dietary-supplements.info.nih.gov/. For those wishing to study herbal products in clinical trials, visit the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine website at http://nccam.nih.gov/.

Manufacturing Quality Botanical Products

Batch-to-batch consistency is also an important measure of a product’s quality, and perhaps one of the most clinically significant aspects a product. Thus, practitioners will want to purchase from companies that have internal standards that allow them to guarantee a consistent product (Box 4-8).

BOX 4-8 Choosing an Herbal Product Brand

From American Herbal Products Association: Herbal FAQs, http://www.ahpa.com

With regard to choosing a brand, one recommendation is to purchase products from companies who are members of the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA). AHPA members agree to abide by a Code of Ethics that requires adherence not only to established regulations, but also to meaningful industry policies. Thus, certain business practices that are not mandated by any government agency are expected of all of these companies. One such measure, established as an industry regulation in 1992, called upon all of AHPA’s members to agree to a single standardized common name for each of the herbs used in their products to ensure clear labeling for consumers. This policy has now been adopted as Federal law. Links to many of AHPA’s members and a copy of the Association’s Code of Ethics are available on the AHPA website: http://www.ahpa.org/. It is also generally recommended that you buy your herbal product from a reputable company. If the claims made on a particular product are outrageous and unbelievable, especially when compared with other products with the same or similar ingredients, it may be an indication to try another brand. Always feel free to contact the manufacturer. Those who are selling high quality products should be happy to answer all of your questions.

Proper Identification

Proper identification is essential to product safety and efficacy. The plant should be identified in the field by the harvester and checked in the manufacturing facility to ensure there has been no mislabeling of the herb between harvest and delivery to the manufacturer. Misidentification (not to mention substitution, contamination, and adulteration) can lead to hazardous consequences for the consumer should a toxic or contraindicated herb replace the desired herb. The classic case illustrating this problem is that of a pregnant woman who was unknowingly consuming an herb called Periploca sepium in place of Eleutherococcus senticosus throughout her pregnancy due to the misidentification or adulteration of a product, and whose baby suffered from androgenization.58 Identity tested can include organoleptic analysis and chemical assay. With whole plant material, organoleptic analysis can often be adequate for identification; however, with powdered herbs, microscopy can be very useful in plant identification, and chemical assays can be necessary because identification of material can be more difficult when the whole herb form is no longer available.

Purity

AHPA recommends specific maximum tolerated levels for dried raw agricultural commodities, including cut and powdered commodities, that are used as botanical ingredients in dietary supplements and that are subject to further processing, as follows:57

Good Manufacturing Practices

Supplements, including herbs, are legally classified as foods and are therefore required to be manufactured to the same high standards that are required of all foods. Good manufacturing practices establish guidelines that assure supplements are manufactured under sanitary conditions, resulting in properly identified products that are not contaminated or adulterated and are fit for consumption. Any supplement that does not conform to these basic guidelines is subject to regulatory action by the FDA.57

Labeling and Marketing

Supplement labels must provide consumers with nutritional information. Unlike foods, supplements must state the quantity of each of the contained ingredients (except for “proprietary blends”) that make up a product. All herbal products are required to identify the parts of each plant ingredient used, and label them with their accepted common names. The FDA specifies exactly what kind of claims are allowed on product labels and prohibits the use of any statement that would brand the product as a drug. Herbal supplements are not allowed to make statements regarding prevention, cure, mitigation, or treatment of diseases. Instead, their claims are limited to statements that are legally defined as “statements of nutritional support” that include “structure/function statements.”57 The FTC guidelines for claims substantiation can be found at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/pubs/buspubs/dietsupp.pdf.