Growth disorders and acromegaly

Normal growth

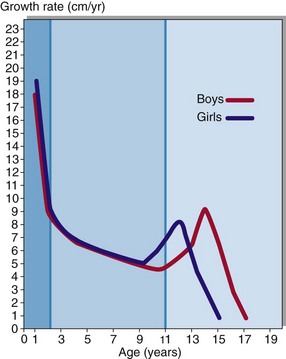

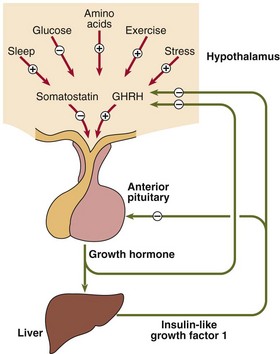

Growth in children can be divided into three stages (Fig 43.1). Rapid growth occurs during the first 2 years of life; the rate is influenced by conditions in utero, as well as the adequacy of nutrition in the postnatal period. The next stage is relatively steady growth for around 9 years and is controlled mainly by growth hormone (GH). If the pituitary does not produce sufficient growth hormone, the yearly growth rate during this period may be halved and the child will be of short stature. The growth spurt at puberty is caused by the effect of the sex hormones in addition to continuing GH secretion. The regulation of GH secretion is outlined in Figure 43.2.

Growth hormone insufficiency

having parents who are both short

having parents who are both short

inherited diseases such as achondroplasia, the commonest cause of severe dwarfism

inherited diseases such as achondroplasia, the commonest cause of severe dwarfism

systemic chronic illness, such as renal disease, gastrointestinal disorders or respiratory disease

systemic chronic illness, such as renal disease, gastrointestinal disorders or respiratory disease

Excessive growth

Hyperthyroidism. An increased growth rate, with advanced bone age, is a feature of hyperthroidism in children, or hypothyroid children over-replaced with thyroxine.

Hyperthyroidism. An increased growth rate, with advanced bone age, is a feature of hyperthroidism in children, or hypothyroid children over-replaced with thyroxine.

Inherited disorders such as Klinefelter’s syndrome (a 47 XXY karyotype). The relative deficiency of testosterone is associated with delayed epiphyseal closure.

Inherited disorders such as Klinefelter’s syndrome (a 47 XXY karyotype). The relative deficiency of testosterone is associated with delayed epiphyseal closure.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. (CAH may cause rapid somatic growth in children, but usually leads to suboptimal adult height due to premature epiphyseal closure, as a result of androgen excess.)

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. (CAH may cause rapid somatic growth in children, but usually leads to suboptimal adult height due to premature epiphyseal closure, as a result of androgen excess.)

Acromegaly

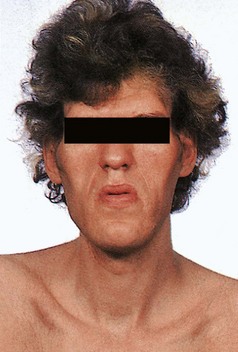

Increased GH secretion later in life, after fusion of bony epiphyses, causes acromegaly (Fig 43.3). The most likely cause is a pituitary adenoma. Clinical features include:

Diagnosis

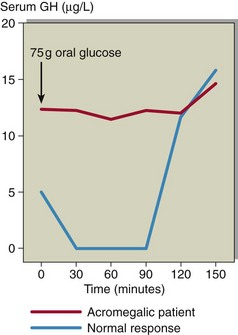

Formal diagnosis of acromegaly requires an oral glucose tolerance test with GH measurement (see pp. 82–83). Acromegalic patients do not suppress fully in response to hyperglycaemia (Fig 43.4), and indeed in some patients a paradoxical rise in GH may be observed.

Treatment

Surgery. Trans-sphenoidal hypophysectomy is the first-line treatment for most acromegalic patients. Its success depends on the size of the tumour.

Surgery. Trans-sphenoidal hypophysectomy is the first-line treatment for most acromegalic patients. Its success depends on the size of the tumour.

Radiation. This is usually reserved for patients whose disease remains active despite surgery. It may take years after pituitary irradiation before safe levels of GH are achieved. Medical treatment is required in the interim.

Radiation. This is usually reserved for patients whose disease remains active despite surgery. It may take years after pituitary irradiation before safe levels of GH are achieved. Medical treatment is required in the interim.

Medical. Dopamine agonists like bromocriptine were widely used in the past, but response rates were low. The advent of long-acting synthetic analogues of somatostatin, such as octreotide, has transformed the medical management of acromegaly. These are expensive drugs with side effects, and it is sensible to screen patients for responsiveness by measuring GH after administering octreotide (octreotide suppression test).

Medical. Dopamine agonists like bromocriptine were widely used in the past, but response rates were low. The advent of long-acting synthetic analogues of somatostatin, such as octreotide, has transformed the medical management of acromegaly. These are expensive drugs with side effects, and it is sensible to screen patients for responsiveness by measuring GH after administering octreotide (octreotide suppression test).