3 Gross Anatomy and General Organization of the Central Nervous System

A useful way to start studying the brain is to learn some of the vocabulary that refers to its major parts, and to understand in a vague way what they do. These major parts can then serve as reference points to build on in later chapters.

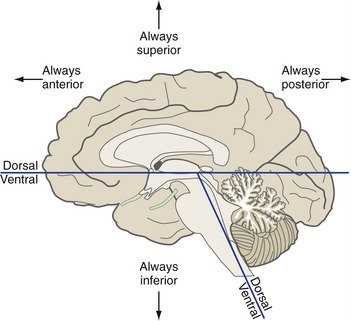

The Long Axis of the CNS Bends at the Cephalic Flexure

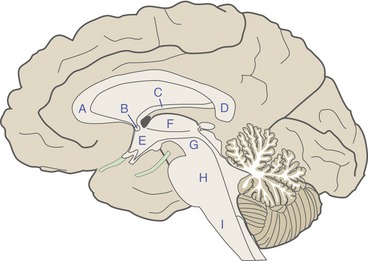

Most creatures move through the world with their spinal cords oriented horizontally. In humans, the cephalic flexure of the embryonic neural tube persists in the adult brain as a bend of about 80° between the midbrain and the diencephalon, allowing us to walk around upright. Terms like dorsal and ventral, however, are used as though the flexure does not exist, the CNS is still a straight tube, and we walk around on all fours. The result is that in the spinal cord and brainstem dorsal has the same meaning as posterior, whereas in the forebrain dorsal has the same meaning as superior (Fig. 3-1).

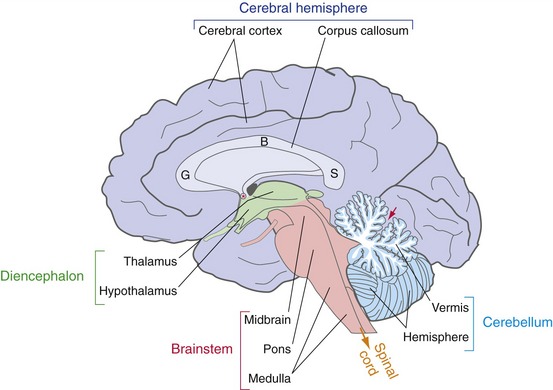

Hemisecting a Brain Reveals Parts of the Diencephalon, Brainstem, and Ventricular System

The cerebral hemispheres of humans are so big that they cover over much of the rest of the CNS. The medial surface of a hemisected brain, however, reveals all the major divisions (Fig. 3-2), still arranged in the same sequence as in the embryonic neural tube: cerebral hemisphere-diencephalon-brainstem/cerebellum-spinal cord.

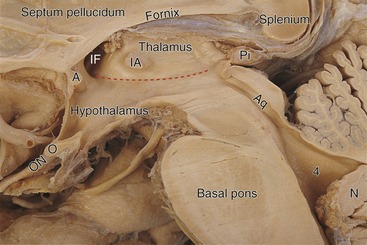

Two fiber bundles interconnect the cerebral hemispheres. The corpus callosum interconnects most cortical areas, extending from an enlarged genu in the frontal lobe through a body to an enlarged splenium in the parietal lobe. The much smaller anterior commissure performs a similar function for parts of the temporal lobes. Beneath the corpus callosum in an accurately hemisected brain is a membrane called the septum pellucidum. This is a paired membrane (one per hemisphere) that separates those parts of the lateral ventricles adjacent to the midline (THB6 Figures 3-19 to 3-21, pp. 69 and 70). At the bottom of the septum pellucidum is the fornix, a long curved fiber bundle carrying the output of the hippocampus (see Fig. 3-6 later in this chapter) from the temporal lobe to structures like the hypothalamus at the base of the brain.

Hemisection passes through the middle of the third ventricle, exposing the thalamus and hypothalamus in its walls (Fig. 3-3). Each interventricular foramen connects the third ventricle to the lateral ventricle of that side. The optic chiasm, in which about half the fibers in each optic nerve cross the midline, is attached to the bottom of the hypothalamus. The pineal gland (part of the diencephalon) is attached to the roof of the third ventricle, near the diencephalon-brainstem junction.

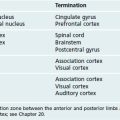

The cerebellum is divided, in one gross anatomical sense, into a midline portion called the vermis (Latin for “worm”) and a much larger hemisphere on each side. In another gross anatomical sense, the deep primary fissure divides the bulk of the cerebellum into an anterior lobe and a substantially larger posterior lobe. Hence the anterior and posterior lobes have both vermal and hemispheral portions. Finally, there is a small flocculonodular lobe. The vermal part (the nodulus) can be seen in Fig. 3-3; the flocculus can be seen in THB6 Figures 3-16 and 3-17, pp. 65 and 66.

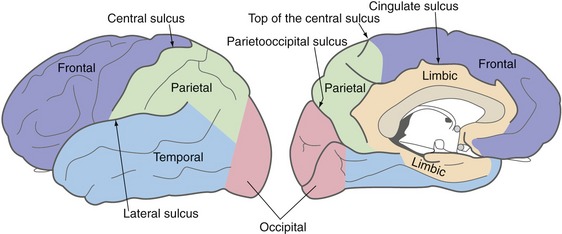

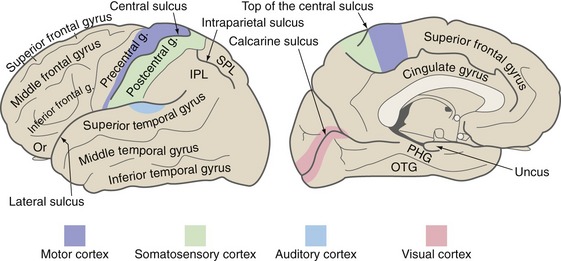

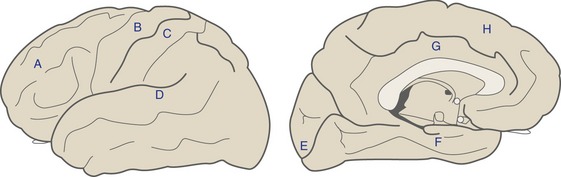

Named Sulci and Gyri Cover the Cerebral Surface

The surface of each cerebral hemisphere is wrinkled up into a series of gyri and sulci, constant from one brain to another in their general configuration but not in their details (THB6 Figure 3-6, p. 58). Four sulci are particularly important for defining the boundaries of cerebral lobes (Fig. 3-4)—the lateral sulcus (= Sylvian fissure) and central sulcus (of Rolando) on the lateral surface of the hemisphere, and the parietooccipital and cingulate sulci on the medial surface.

Each Cerebral Hemisphere Includes a Frontal, Parietal, Occipital, Temporal, and Limbic Lobe

The frontal lobe is above the lateral sulcus and in front of the central sulcus. The parietal lobe is right behind the frontal lobe, extending back to the occipital lobe (which is defined by landmarks more easily visible on the medial surface of the hemisphere). The temporal lobe is below the lateral sulcus. All four of these lobes continue onto the medial surface of the hemisphere, extending as far as the limbic lobe. The limbic lobe is a ring of cortex that encircles the junction between the cerebral hemisphere and the diencephalon. In addition, the insula, not part of any of the preceding lobes, is buried in the lateral sulcus, covered over by parts of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (see Fig. 2-6; and see THB6 Figure 3-8, p. 60).

The lateral surface of the frontal lobe is made up of the precentral gyrus and the superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri (Fig. 3-5). The precentral gyrus is located immediately in front of the central sulcus and most of it is primary motor cortex (i.e., much of the corticospinal tract originates here). The other three are broad, parallel gyri that extend anteriorly from the precentral gyrus. The precentral and superior frontal gyri extend over onto the medial surface of the frontal lobe, where they end at the cingulate sulcus. The inferior (or orbital) surface of the frontal lobe is made up of a series of unnamed orbital gyri together with gyrus rectus, which is located adjacent to the midline.

The major components of the limbic lobe are the cingulate and parahippocampal gyri. The cingulate gyrus curves around adjacent to the corpus callosum, interposed between it and the frontal and parietal lobes. Near the splenium of the corpus callosum the cingulate gyrus is continuous with the parahippocampal gyrus, which proceeds parallel to the occipitotemporal gyrus. At its anterior end the parahippocampal gyrus folds back on itself to form a bump called the uncus. The parahippocampal gyrus received its name because it is continuous with a cortical region called the hippocampus, which is rolled into the interior of the hemisphere and visible only in sections (see Fig. 3-6).

The Diencephalon Includes the Thalamus and Hypothalamus

Each region of the diencephalon contains the term “thalamus” in its name. The epithalamus includes the pineal gland and a few other small structures. The subthalamus, completely surrounded by other parts of the CNS, includes an important component of the basal ganglia (see Chapter 19). The thalamus and hypothalamus form the walls of the third ventricle. Most pathways headed for the cerebral cortex involve a synapse in the thalamus (see Chapter 16), which controls access to the cortex. The hypothalamus (see Chapter 23) controls the autonomic nervous system and gets involved in various aspects of drive-related behaviors.

The Cerebellum Includes a Vermis and Two Hemispheres

There are several different ways to divide up the cerebellum (see Chapter 20), but subdividing it into longitudinal strips (i.e., perpendicular to the mostly transverse sulci and fissures) corresponds best to the way the cerebellum is wired up functionally. On a gross level, the whole cerebellum can be divided into a longitudinal midline strip called the vermis (mostly concerned with coordinating trunk movements), flanked on each side by a cerebellar hemisphere (mostly concerned with coordinating limb movements).

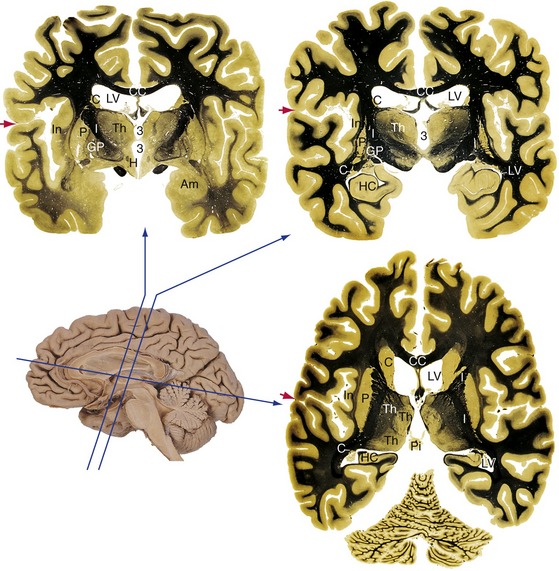

Sections of the Cerebrum Reveal the Basal Ganglia and Limbic Structures

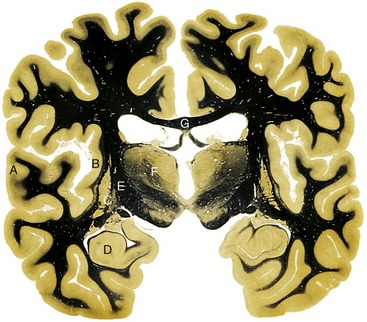

A number of forebrain structures are completely enveloped by the cerebral hemispheres and cannot be seen without sectioning the brain (Fig. 3-6). Coronal sections reveal the general arrangement of these structures; horizontal sections help to reveal their extent.

A thick bundle of fibers called the internal capsule runs between the lenticular nucleus and the thalamus; it continues anteriorly between the lenticular nucleus and the head of the caudate nucleus. The internal capsule is the principal route through which fibers travel between the cerebral cortex and subcortical sites. For example, the corticospinal tract travels through the internal capsule, as do somatosensory fibers from the thalamus to the cortex.

Underlying the uncus in the more anterior of the two coronal sections in Figure 3-6 is a large nucleus called the amygdala, an important component of the limbic system. Just posterior to it, in the other coronal section, is the most anterior part of the hippocampus, a cortical structure that has been folded into the temporal lobe. The hippocampus is another major component of the limbic system.

Parts of the Nervous System Are Interconnected in Systematic Ways

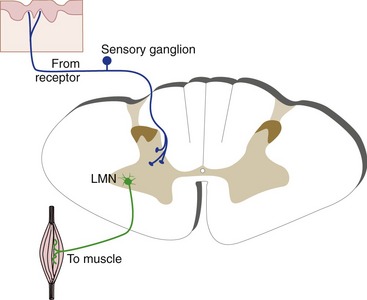

Axons of Primary Afferents and Lower Motor Neurons Convey Information to and from the CNS

The CNS communicates with the rest of the body primarily through sensory neurons and motor neurons. Primary afferent neurons convey information into the CNS; some have specialized receptive endings outside the CNS and others have peripheral endings that receive connections from separate receptor cells. Primary afferents typically have their cell bodies in ganglia adjacent to the CNS, and central processes that synapse in the CNS. (A CNS neuron on which a primary afferent synapses is called a second order neuron, which in turn synapses on a third order neuron, etc.) With few exceptions, the receptive endings, cell body, and central terminals of primary afferents are all on the same side (Fig. 3-7). Motor neurons that innervate skeletal muscle (also called lower motor neurons) have their cell bodies within the CNS but, like primary afferents, they are almost always connected to ipsilateral structures.

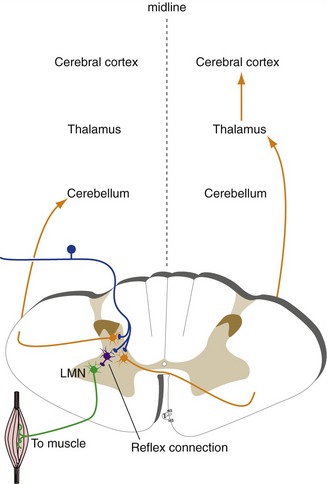

Somatosensory Inputs Participate in Reflexes, Pathways to the Cerebellum, and Pathways to the Cerebral Cortex

Most kinds of sensory information divide into three streams after entering the CNS (Fig. 3-8), each stream usually being actually a series of parallel creeks. The first stream feeds into local reflex pathways, the second is directed to the cerebral cortex, and the third to the cerebellum. The information that reaches the cerebral cortex is used in our conscious awareness of the world, as well as in figuring out appropriate behavioral responses to what’s going on out there. The information that reaches the cerebellum, in contrast, is used in motor control; someone with cerebellar dysfunction moves abnormally but has normal awareness of the abnormal movements.

Somatosensory Pathways to the Cerebral Cortex Cross the Midline and Pass through the Thalamus

Somatosensory pathways to the cerebral cortex contain at least three neurons (some contain more): a primary afferent, a second order neuron that projects to the thalamus, and a third order neuron that projects from the thalamus to the cortex. In the case of somatic sensation, one side of the body is represented in the cerebral cortex of the opposite side. Because neither primary afferents nor thalamocortical neurons have axons that cross the midline, it follows that second order neurons are the ones with crossing axons. One key to understanding the organization of sensory pathways is knowing the location of the second order neurons (THB6 Figure 3-29, p. 76).

Other Sensory Systems Are Similar to the Somatosensory System

The somatosensory system is representative in most ways of sensory systems in general. Other systems feed into reflex arcs, reach the cerebellum, have distorted maps, and take at least three neurons to reach the cerebral cortex. (The only exception is the olfactory system, which bypasses the thalamus). The big area of variability is in crossing the midline; some pathways are uncrossed (e.g., taste, olfaction) and others are bilateral. The auditory system, for example, has bilateral projections at the level of second order neurons (see Fig. 14-5), used for localizing sounds by comparing information from the two ears.

Higher Levels of the CNS Influence the Activity of Lower Motor Neurons

Lower motor neurons receive inputs from multiple sources (just as primary afferent information is distributed to multiple places). There are more details in Chapter 10Chapter 18Chapter 19Chapter 20, but basically, the sources are upper motor neurons in the cerebral cortex and brainstem, together with local reflex connections. The cerebellum and basal ganglia also affect lower motor neurons, but not directly.

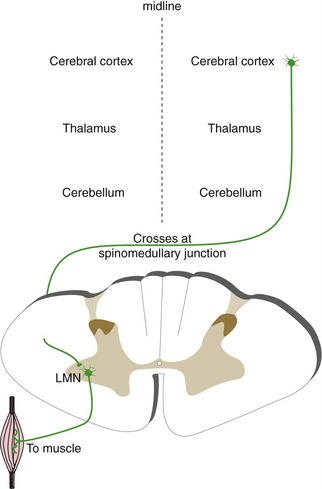

Corticospinal Axons Cross the Midline

Signals for the initiation of voluntary movements issue from the cerebral cortex. The thalamus is not a relay in pathways leaving the cerebral cortex, and there is a large corticospinal tract that projects directly from cortex to spinal cord (and an analogous corticobulbar tract that projects to cranial nerve motor nuclei). Most corticospinal fibers, consistent with the pattern in the somatosensory system, cross the midline (Fig. 3-9).

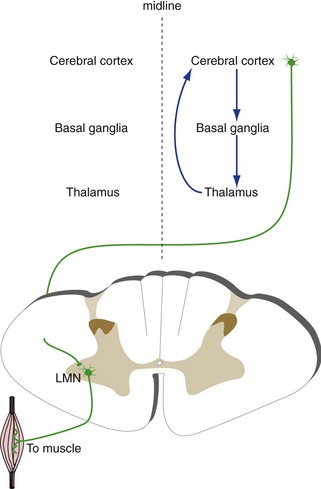

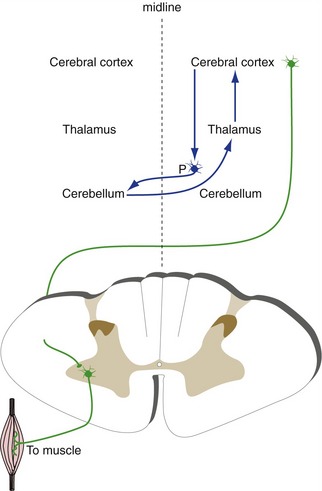

The Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum Indirectly Affect Contralateral and Ipsilateral Motor Neurons, Respectively

The basal ganglia and the cerebellum are also involved in control of movement. However, both work not by influencing motor neurons directly, but mostly by affecting the output of motor areas of the cortex. Connections between the basal ganglia and the cerebral cortex for the most part do not cross the midline (Fig. 3-10), so one-sided damage to the basal ganglia causes contralateral deficits. In contrast, connections between the cerebrum and the cerebellum are crossed (Fig. 3-11), consistent with the observation that one-sided cerebellar damage causes ipsilateral deficits. Because the cerebellum and basal ganglia affect motor but not sensory areas of the cortex, damage to the cerebellum or basal ganglia does not cause changes in basic sensation.