Chapter 20. Granulomatous disorders and tumours

Granulomatous conditions

There are three disorders of the reticuloendothelial system that affect bone; all are rare, but they are important because they can be mistaken for tumours:

1. Eosinophilic granuloma.

2. Hand–Schüller–Christian disease.

3. Gaucher’s disease.

Eosinophilic granuloma

The lesions of eosinophilic granuloma are ‘punched-out’ holes in the skull and elsewhere. Radiologically, the lesions resemble metastases or bone cysts (Fig. 20.1). The ‘holes’ contain a soft brown tissue.

|

| Fig. 20.1

Eosinophilic granuloma of the rib.

|

The condition is not fatal and may regress spontaneously.

Hand–Schüller–Christian disease

This condition is similar to eosinophilic granuloma except that the lesions are paler and the brain is often involved, particularly around the pituitary. The condition is slowly progressive and may be fatal.

Gaucher’s disease

Gaucher’s disease is a systemic disorder in which an abnormal fatty substance (kerasin) is deposited in the liver and other tissues. Bone involved in Gaucher’s disease contains irregular cysts and cavities visible radiologically. Affected bones, particularly the femoral head and condyles, may collapse and make joint replacement necessary.

Tumours

Radiological appearance of bone tumours

When looking at bone tumours on a radiograph, ask the following questions:

Classification of bone tumours

The classification of bone tumours should reflect the cell of origin. They can be further subclassified into benign and malignant tumours (Table 20.1).

| Benign | Malignant | |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrogenic | Simple cyst | Malignant fibrous |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | Hystiocytoma | |

| Fibrous dysplasia | ||

| Fibrous cortical defect | Fibrosarcoma | |

| Chondrogenic | Enchondroma | Chondrosarcoma |

| Periosteal chondroma | ||

| Osteochondroma | ||

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | ||

| Chondroblastoma | ||

| Osteogenic | Osteoid osteoma | Osteosarcoma |

| Osteoblastoma | ||

| Ossifying fibroma | ||

| Unknown origin | Giant cell | Ewing’s |

| Synovial sarcoma | ||

| Bone marrow | Myeloma | |

| Lymphoma |

Simple bone islands (Fig. 20.2) are of no particular significance, although they are often striking on X-ray.

|

| Fig. 20.2

Cortical bone islands.

|

Benign bone tumours

Fibrogenic

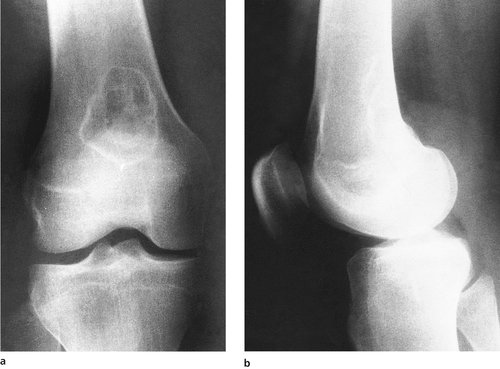

Fibrous cortical defect (Fig. 20.3). This most common abnormality has a characteristic oval X-ray appearance with a sharp margin and often multilocular. No specific treatment is required.

|

| Fig. 20.3

(a), (b) Fibrous cortical defect at the lower end of femur.

|

Fibrous dysplasia. This can present in mono- or polyostotic forms and is seen more commonly between the second and third decades. The radiographic appearance is of a ground-glass expansile lesion, often with a bowing of the affected bone. A ‘shepherd’s crook’ deformity is seen in the proximal femur as a result of this bowing and possible multiple fractures. The polyostotic form can be associated with hypothyroidism, vitamin D-resistant rickets and the Cushing syndrome. Albright’s syndrome includes the polyostotic dysplasia with café-au-lait spots and precocious puberty. The lesions are reasonably characteristic on X-ray but occasionally a biopsy is required. When painful, these are adequately treated with curettage and bone grafting. Occasionally there can be an associated fracture, although this is rare.

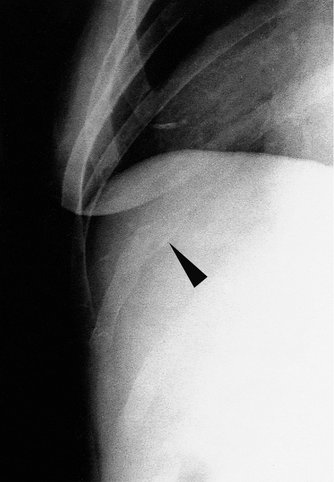

Simple bone cyst (Fig. 20.4). These cysts may occur during growth and are commonly located adjacent to the epiphyseal plate. They are usually asymptomatic until pathological fracture occurs. The radiographic appearances show a well defined radiolucent lesion, often with this pathological fracture.

|

| Fig. 20.4

(a) A pathological fracture through a simple bone cyst of the humerus; (b) the fracture has united and the bone cyst is less obvious.

|

Bone scans confirm a decreased uptake in the area and treatment is unnecessary unless there is a risk of fracture. These cysts can heal spontaneously after a fracture, but when in doubt aspiration and an injection of methylprednisolone acetate has an 80–90% success rate. Curettage and bone grafting is occasionally necessary.

Aneurysmal bone cyst (Fig. 20.5). These cystic cavities contain a thick brown-coloured membrane containing blood. They may occur in any bone, including the vertebrae. Approximately 50% are primary and 50% are the result of a benign lesion such as a chondroblastoma.

|

| Fig. 20.5

Aneurysmal bone cyst at the upper end of the fibula. It has not crossed the epiphyseal plate.

|

Radiographic signs confirm an expansile eccentric lesion and a thin ‘eggshell’ ring of bone. A CT scan may demonstrate a fluid level within the cyst. Treatment is usually by curettage andbone grafting.

Osteogenic

Osteoid osteoma (Fig. 20.6 and Fig. 20.7). Any bone can be involved but more commonly the femur, tibia and vertebrae. There is a characteristic nidus in the cortical lesions, demonstrated on CT. Patients often have pain, which is particularly worse at night and can be relieved by aspirin. The natural history is thought to be self-limiting and resolution of symptoms has been described. Treatment has traditionally been surgical excision, although it is often difficult to localize the lesion. Guided laser ablation has shown encouraging results.

|

| Fig. 20.6

Juxtacortical osteoid osteoma of the tibia.

|

|

| Fig. 20.7

(a) Isotope scan to show an osteoid osteoma in the left tibia of a growing child; (b) lateral view of the left tibia to show the position of the osteoid osteoma on the anterior cortex.

|

Ossifying fibroma. These are often considered to be a variation of fibrous dysplasia and are located eccentrically, either in the tibia or the fibula in young children. Occasional rapid expansion with or without a fracture is noted, but surgery is rarely indicated.

Chondrogenic

Enchondroma (Fig. 20.8). These benign tumours of mature hyaline cartilage are usually located centrally within the diaphysis of long bones and may represent the remnant of the epiphyseal plate. They can be solitary or multiple (Ollier’s disease) or associated with skin haemangiomas (Maffucci syndrome). Less frequently these lesions are located at the periosteum and are either juxtacortical or subperiosteal chondromas. These often involve the small tubular bones of the hand and feet and are noted more commonly in the second, third and fourth decades. Malignant transformation has been reported. Radiographic signs are characteristic, with an expansile nature of the bone, often with punctate calcification within. Treatment by curettage and bone grafting is occasionally required but patients should remain under review, especially with large tumours of the pelvis or spine.

|

| Fig. 20.8

An enchondroma of the proximal phalanx of the middle finger. The distal part of the middle and ring fingers have suffered a previous traumatic amputation.

|

Osteochondroma (Fig. 20.9). These are the most common benign bone tumours and probably represent a disorder of the normal enchondral bone growth. The appearance is either sessile or of a pedunculated lesion arising from the cortex of a long bone, adjacent to the physis (exostosis). Unlike a true neoplasm, the growth normally parallels that of skeletal maturity and is often noted during periods of rapid skeletal growth. Ninety per cent are single, but in 10% multiple osteochondromas occur. Most lesions are asymptomatic but can cause irritation of the surrounding structures (muscle, ligament). The clinical findings are usually of a palpable mass.

|

| Fig. 20.9

An isolated exostosis of the upper end of the tibia pointing away from the growing epiphysis.

|

A cartilaginous cap of a few millimetres thickness usually covers the lesion. Large lesions can result in growth abnormalities (ulna bowing, etc.). Malignant transformation is possible and may occur in 10–25% of cases, although the exact incidence is unknown.

Chondroblastoma. This rare tumour occurs between 5 and 25 years of age, more commonly in the knee, hip and shoulder area. The tumour usually involves the physis and patients tend to present with pain. The lesion is lytic, with calcification occurring in approximately 50% of cases. Secondary aneurysmal bone cysts may occur. These chondroblastomas are aggressive, benign tumours but metastases can occur. In common with giant cell tumours, they should be regarded as potentially malignant.

Chondromyxoid fibroma. These occur eccentrically in the metaphysis of the proximal tibia commonly. Treatment includes curettage and bone grafting.

Undetermined aetiology

Giant cell tumour (Fig. 20.10). This occurs commonly in the third and fourth decade and more commonly around the knee or distal radius. The radiographic features are of an expansile lesion, which often lies eccentrically. The border is well defined with some sclerosis and is often juxtaposed to the articular cartilage. Pathological fracture is common and treatment includes surgical removal with curettage and bone grafting, with or without phenol ablation, cryosurgery or instillation of methylmethacrylate.

|

| Fig. 20.10

Giant cell tumour in the radius extending right up to the joint margin.

|

Primary malignant bone tumours

Fibrogenic

Malignant fibrous hystiocytoma (MFH) is a high grade tumour seen in adulthood. It commonly occurs around the metaphysis, in particular of the knee. Radiographs show a ‘moth-eaten’ osteolytic lesion with extensive cortical disruption but a minimal periosteal reaction and very little, if any, new bone formation. The underlying cell of origin is doubtful and treatment is difficult. The prognosis is unfavourable.

Osteogenic

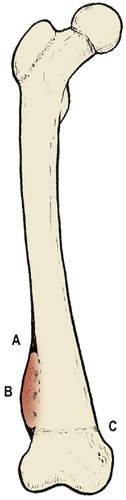

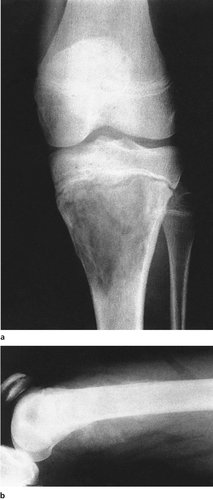

Osteogenic sarcoma (Fig. 20.11 and Fig. 20.12). These are the most common primary bone tumours and occur more commonly in children and young adults (Fig. 20.11). The tumour often presents as a swelling with a history of minimal trauma. The tumours are classified as primary or secondary (following Paget’s disease, X-ray therapy). The primary tumours are further classified according to their position (parosteal, central or multicentric).

|

| Fig. 20.11

Radiological features of osteogenic sarcoma: ( A) Codman’s triangle at the margins of the tumour; ( B) ‘sunrise’ spicules of calcification within the tumour; ( C) site at growing end of a long bone.

|

|

| Fig. 20.12

(a) Osteogenic sarcoma at the upper end of the tibia in a girl aged 12 years; (b) osteogenic sarcoma at the lower end of the femur showing the classic ‘sun ray’ cacification.

|

Approximately 70% of patients present without a detectable metastasis, but in the 30% that do there is a high percentage of relapse following chemotherapy and local surgery. Limb sparing resection is possible with adjuvant chemotherapy. The prognosis for all types is poor.

Radiographic signs confirm the lytic lesion, elevation of the periosteum and the production of a ‘Codman’s triangle’.

Chondrogenic

Chondrosarcomas. These may be classified as central or peripheral, or primary versus secondary (secondary to a pre-existing lesion such as an osteochondroma). Patients usually present with a long history of pain, mass or both. These tumours are further differentiated into low, intermediate or high grade lesions. The behaviour of the tumour is related to the aggressive portion of the lesion and the prognosis is poor.

Cells of unknown origin

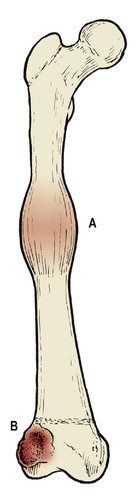

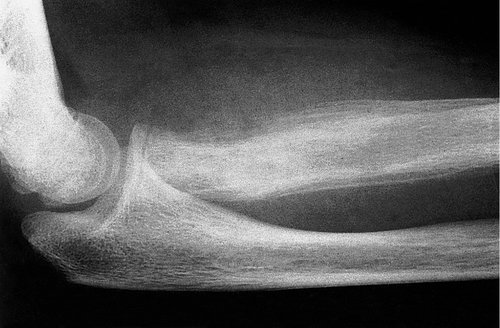

Ewing’s sarcoma (Fig. 20.13 and Fig. 20.14). This rare tumour occurs in the first and second decade of life and the small, primitive, round cells have a common karyotypic translocation between chromosome 11 and 22. Previously these were uniformly fatal, but major advances in treatment have been made with the use of chemotherapy and adequate local control. The most important adverse prognostic feature is metastatic disease detectable at the time of diagnosis. The 5-year relapse-free survival rate is 20% for those with metastatic disease, compared with 55% for those without metastases at the time of presentation.

|

| Fig. 20.13

( A) Ewing’s sarcoma, which may arise anywhere along the shaft of a long bone. ( B) Giant cell tumour appearing as a multilocular cyst in the epiphysis, but not crossing the line of the epiphysis.

|

|

| Fig. 20.14

Ewing’s sarcoma in the radius showing ‘onion skin’ layering.

|

Surgical resection is considered the optimal method of obtaining local control. The radiographic appearances include bone destruction with an ‘onion skin’ reaction of the periosteum. It may involve large areas of the diathesis and may appear to skip areas of the bone.

Synovial sarcoma. This tumour has histological similarities with the synovium of joint but rarely arises directly from the joint. They are often of a high grade histological appearance but may be well circumscribed or multinodular. Soft tissue calcification occurs in approximately 25% of cases and lymphatic and vascular metastatic spread is common, with a poor long-term prognosis.

Tumours of bone marrow

Myeloma. This is a tumour derived from the plasma cells (highly differentiated B lymphocytes). Presentation includes pain and anaemia in the fifth and sixth decade of life. A monoclonal gammopathy with an elevated M-spike is characteristic. Bence Jones proteins may be demonstrated in the urine. Radiographic changes include multiple ‘punched out’ lesions of the bones and bone scan appearances may be unusual.

Solitary lesions (plasmocytomas) are seen infrequently and aggressive radiotherapy is the treatment of choice.

Lymphoma of bone. These are usually a sign of disseminated disease and rarely represent a primary tumour. The tumour characteristically presents in the third to fifth decades of life and radiographs may show a ‘moth-eaten’ appearance. Treatment is by chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Metastatic bone tumours

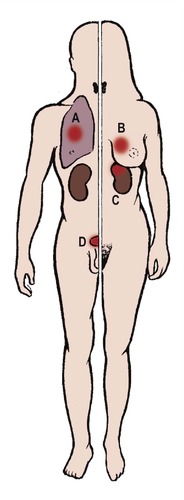

The commonest malignant bone tumours are secondary deposits (Fig. 20.15). The tumours that most commonly metastasize to bone (Fig. 20.16) are bronchus, breast, prostate and renal cell carcinomas.

|

| Fig. 20.15

Metastatic deposits in the femur. Note the clear punched-out margins.

|

|

| Fig. 20.16

Tumours that commonly metastasize to bone: ( A) bronchus; ( B) breast; ( C) hypernephroma; ( D) prostate.

|

Tumours that metastasize to bone most often (Fig. 20.16)

1. Lung.

2. Breast.

3. Prostate.

4. Renal cell carcinoma.

Treatment

Treatment depends upon the tumour but may involve radiotherapy, chemotherapy or hormone therapy. If pathological fracture occurs, intramedullary nailing is indicated. It is wise to nail the bone prophylactically in those lesions that involve more than 50% of the circumference of the bone to avoid an impending fracture.

An MRI scan of the bone can delineate the extent of the secondary deposit.

Case reports

These three cases represent different presentations of swelling around the knee.

Patient A

An 18-year-old gentleman presented with a painless swelling on the medial side of his right knee. He had noticed a slight increase in size over the last few months, but related the swelling to a minor injury he had while playing football some 3 months previously. The swelling failed to settle and he eventually attended his general practitioner.

A plain radiograph was requested and the radiologist’s report suggested an urgent orthopaedic review. The plain radiograph confirmed what appeared to be an osteogenic sarcoma and the patient was subsequently transferred to a bone tumour unit for further management.

Patient B

A 14-year-old boy who was a very keen sportsman noticed a pain on the inner side of his right knee. This pain was associated with a small lump, which he thought was growing in size. He could not remember having injured the knee specifically, but did notice that the pain was getting increasingly severe and was affecting his day-to-day activities.

When reviewed in the orthopaedic department it was noted that he had a small, hard, bony lump on the proximal medial aspect of his right tibia. Plain radiographs confirmed that this was a benign osteochondroma. After careful palpation of the other leg and arms it was clear that this was an isolated osteochondroma. There was no family history to suggest a hereditary link. The patient subsequently underwent an uneventful removal of this bony lump with the cartilagenous cap intact. Histology showed no evidence of malignancy.

Patient C

A 14-year-old boy was admitted with a painful lump over the medial aspect of the proximal tibia. He had noticed this lump increasing in size over the last few weeks. He had been generally unwell and over the last few days had suffered shivers and a fever.

It was thought that he had a recent upper respiratory tract infection, but this had been minor.

On examination he was pyrexial with a tachycardia. The swelling over the proximal tibia was warm and tender. Plain radiographs confirmed a lytic area in the proximal tibia and laboratory investigations confirmed a high ESR and CRP. It was felt that this was an osteomyelitis. The abscess was drained and irrigated thoroughly. Appropriate antibiotics were given and the patient made an uneventful recovery in the long term.

Summary

Swellings around the knee can be simple cysts or benign bony lumps, but it must be remembered that more sinister tumours often present in the younger age group with a slightly tenuous history of previous trauma preceding this. Similarly, infections, although rare in the developed world, are still frequently seen.

Management of malignant tumours should be undertaken in a specialist bone tumour centre where the results of treatment are greatly improved.