30 Granulomatous Disease

Noninfectious granulomatous disease is rare in children, with the exception of Crohn disease (see Chapter 110). This group of diseases includes sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitides (Wegener granulomatosis [WG] and Churg-Strauss syndrome [CSS]), and familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Blau syndrome).

Sarcoidosis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

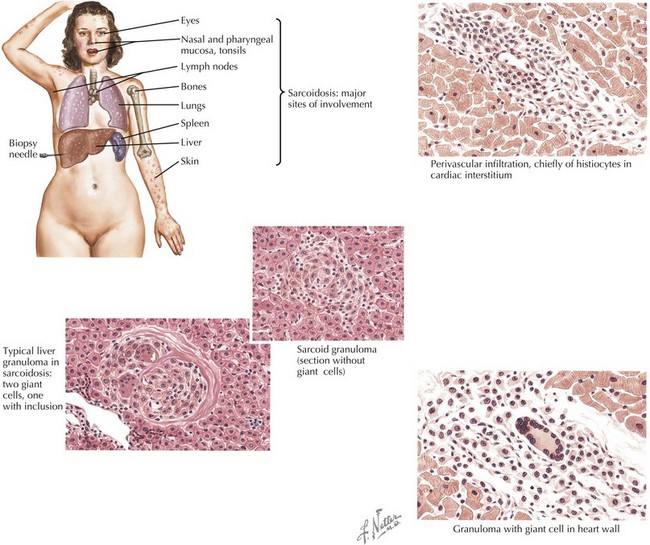

Sarcoidosis is characterized by granulomas consisting of tightly packed epithelioid cells and macrophages surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 30-1). In the lung, CD4+ T cell-mediated alveolitis occurs early followed by granuloma formation. Granulomas may resolve without sequelae or may heal with residual fibrosis.

Clinical Presentation

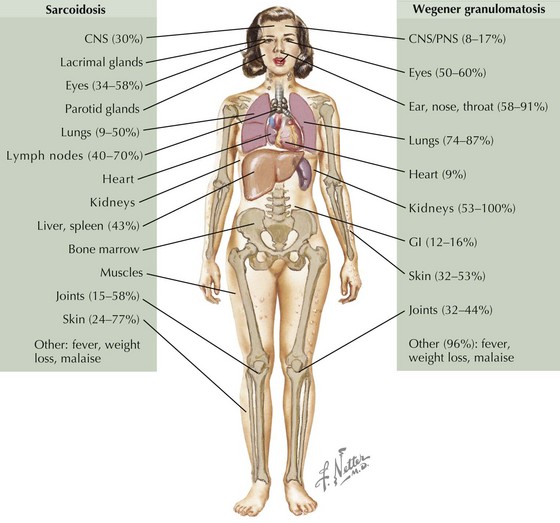

Sarcoidosis in children occurs in two distinct forms. Older children (age 8-15 years) typically present with symptoms resembling the adult form of disease, including lymphadenopathy, lung involvement (often asymptomatic), systemic signs (fever, weight loss), and hypercalcemia, but rarely with joint involvement. In children younger than 5 years, the onset typically consists of the triad of rash, arthritis, and uveitis. Sarcoidosis commonly presents with lymphadenopathy and may affect a wide range of organs (Figure 30-2).

Differential Diagnosis

Sarcoidosis should be considered in any child presenting with nonspecific findings, including fever, weight loss, and lymphadenopathy, especially if accompanied by rash, arthritis, or hilar adenopathy, or in any child with fever of unknown origin (see Chapter 86, Figure 86-1). Other conditions that must be considered in a child suspected of having sarcoidosis include infections, malignancies, and other rheumatic illnesses (vasculitides, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], mixed connective tissue disease [MCTD], Sjögren syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis [JIA]). Hilar adenopathy with constitutional symptoms may mimic lymphoma. After granulomatous inflammation has been established, infections must be ruled out before initiation of immunosuppressive medications (Box 30-1).

Evaluation and Management

Histology

Biopsy-proven granulomatous inflammation is vital to the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Tissue should be sampled from the most accessible site (preferably superficial lymph nodes), which may be determined by imaging (e.g., FDG-PET) if not clinically apparent. Typical histology includes noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas; however, this is not specific and does not distinguish sarcoidosis from other granulomatous diseases, including infections. Specific stains and cultures for granulomatous infections should be performed (see Box 30-1).

Wegener Granulomatosis

Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis depends on presentation and often requires evaluating for other causes of nonspecific systemic symptoms, such as fever and malaise or fever of unknown origin (see Chapter 86, Figure 86-1). Infectious causes of granulomatous vasculitis must be considered (see Box 30-1). Other rheumatologic illnesses (sarcoidosis, CSS, microscopic polyangiitis, SLE, MCTD, Sjögren syndrome, and Goodpasture syndrome) and chronic granulomatous disease (especially in young children) should be considered.

Evaluation and Management

Lindsley CB, Laxer RM. Granulomatous vasculitis, giant cell arteritis, and sarcoidosis. In: Cassidy JT, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Rheumatology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:539-560.

O’Neil KM. Progress in pediatric vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(5):538-546.

Ianuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16-25.

Akikusa JD, Schneider R, Harvey EA, et al. Clinical features and outcome of pediatric Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:837-844.

Frosch M, Foell D. Wegener granulomatosis in childhood and adolescence. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:425-434.