Gram-Negative Cocci and Coccobacilli

• Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are strict human pathogens; other Neisseria species are commonly present on mucosal surfaces.

• Gram-negative, nonmotile, coffee bean–shaped diplococci

• Loosely attached outer membrane that is readily shed, releasing lipooligosaccharide (LOS) into the host

• N. meningitidis enters the respiratory tract, invades mucous membranes, and spreads via the bloodstream.

• Antiphagocytic capsule is important for virulence.

• Released endotoxin induces fever and increases vascular permeability, potentially leading to shock and petechiae (capillary leakage in skin).

• Meningococcal infection is most common in children younger than 5 years of age and in those with deficiency of terminal complement components (C5-C9).

a. Septicemia with or without meningitis

b. Characterized by fever, shock, and generalized hemorrhage ranging from petechiae to purpura

c. Can be rapidly fatal (mortality rate of 25% or higher) if not treated promptly

• Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome

a. Complication of meningococcemia

b. Marked by overwhelming disseminated intravascular coagulation and bilateral hemorrhagic adrenal infarctions with septic shock, acute hypotension, tachycardia, and petechiae

• Mild febrile disease with pharyngitis, pneumonia, arthritis, or urethritis

4. Transmission of N. meningitidis

• Person-to-person spread from infected persons

• Inhalation of aerosol droplets (often from asymptomatic posterior nasopharyngeal carriers)

• Breastfeeding infants for the first 6 months of life

• Active immunization of children older than 2 years of age with a polyvalent conjugate, anticapsular vaccine (not effective against serogroup B)

• Postexposure prophylaxis with rifampin, quinolones, or sulfonamides (only if the organism is proved susceptible)

1. Thayer-Martin medium (selective chocolate agar)

• Used for isolating N. gonorrhoeae in specimens from nonsterile areas, such as the cervix and urethra

• Contains vancomycin (kills gram-positive bacteria), colistin (kills gram-negative bacteria except Neisseria species), and nystatin (kills fungi)

• Pili (fimbriae) and outer membrane protein II (OMPII) promote adherence to and invasion of mucosal cells.

• IgA protease cleaves secretory IgA, reducing host defense to gonococcal infection.

• Endotoxin causes fever, vascular permeability, inflammation, and tissue destruction.

• Antibiotic resistance, especially due to β-lactamase, is common.

• Antigenic variation of surface proteins permits escape from antibody response.

3. Gonococcal diseases (Box 12-1)

• Sexually active individuals with multiple partners are at greatest risk for N. gonorrhoeae infection, which is spread primarily by sexual contact.

• Acute gonococcal infection (gonorrhea)

• Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

a. Infection of the uterus, fallopian tubes (salpingitis), and/or ovaries

b. An ascending infection that may result in infertility and predisposes to ectopic pregnancy

c. Pus collecting under the right diaphragm causes scar tissue formation between the diaphragm and liver surface causing pain with movement (Fitz-Hughes-Curtis syndrome)

• Neonatal conjunctivitis resulting from infection during delivery by infected mother

b. Septic arthritis, dermatitis-arthritis syndrome, bacteremia (skin lesions, fever, joint pain), endocarditis

c. Deficiency of a terminal complement component (C6-C9) predisposes to disseminated disease.

• Gonococcal urethritis and cervicitis: treatment should be directed against C. trachomatis as well as N. gonorrhoeae because dual infection is common.

a. Antigonococcal drugs include cefixime, ceftriaxone, and azithromycin.

b. Antichlamydial drugs include tetracycline, doxycycline, ofloxacin, and azithromycin.

• Disseminated or bacteremic illness: prolonged therapy with penicillin or ceftriaxone is required.

1. Filamentous hemagglutinin binds to ciliated epithelial cells, particularly in the nasopharynx and trachea.

2. Survival within phagocytic cells protects B. pertussis from circulating antibodies and permits long-term carriage within the lungs.

3. Several exotoxins and endotoxins mediate disease manifestations and increase virulence of B. pertussis (Table 12-1).

TABLE 12-1

| Toxin | Biologic effects |

| Pertussis toxin (A-B type exotoxin) | Toxic A subunit enters cell and ADP-ribosylates inhibitory G protein, turning it off. The subsequent increased cAMP level leads to loss of fluids and electrolytes, lymphocytosis, and massive mucus secretion in the respiratory tract. |

| Adenylate cyclase toxin | Enters host cells and increases cAMP production, which blocks immune effector function and prevents clearance of the bacteria |

| Tracheal cytotoxin | Inhibits and damages ciliated tracheal cells |

| Endotoxin | Causes fever and other pyrogenic responses |

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

1. Occurs primarily in unvaccinated children and adults with waning immunity

2. Transmitted by inhalation of infectious aerosols

3. Toxin inhibits signal transduction by chemokine receptors, which prevents lymphocytes from entering lymph nodes, leading to profound lymphocytosis.

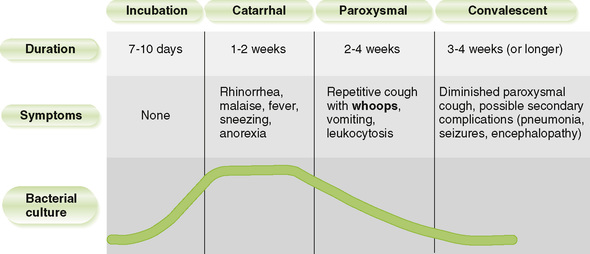

4. Disease progresses from common cold–like to paroxysmal to convalescent stages (Fig. 12-1).

1. Inactivated whole cell vaccine administered as part of the DPT (diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus) vaccine or multivalent acellular vaccine (DTaP) (at 2, 4, 6, and 16 months and at 5, 11, 19, and 65 years of age)

2. Macrolide (or similar) antibiotic early in disease and for nonimmune individuals who have been exposed

3. Prophylactic macrolide (or similar) antibiotic for close contacts of patient with symptoms

• Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus ducreyi are the most medically important Haemophilus species.

A Shared properties of Haemophilus species

1. Small, gram-negative coccobacillus

2. Obligate parasites found on mucous membranes of humans and some animals

3. Factor X (hemin) and/or factor V (NAD) required for growth

• Antiphagocytic capsule is critical virulence factor.

a. H. influenzae type b (Hib), the most virulent of the six capsule types, invades the mucosa, enters the blood, and spreads throughout the body, causing systemic diseases.

b. Nonencapsulated H. influenzae is part of the normal flora of the upper respiratory tract and may cause localized opportunistic infections.

• Endotoxin induces inflammation and contributes to the symptoms.

2. Diseases caused by H. influenzae

• Systemic infection primarily affects unimmunized young children and is spread by respiratory droplets.

• Meningitis in infants (3 to 18 months of age)

a. Mild respiratory disease of short duration is followed by bacteremia and then meningitis.

• Epiglottitis in children (2 to 4 years of age)

a. Cellulitis and swelling of the epiglottis can block breathing.

c. Lateral radiograph shows swelling of the epiglottis (“thumbprint” sign).

• Cellulitis in the cheek of very young children

a. Infection begins in buccal mucosa and spreads to the face and neck, causing swelling, blue-red patches on skin, and fever.

• Arthritis affecting single large joints in children younger than 2 years of age

• Otitis, sinusitis, and bronchitis are caused by encapsulated and nonencapsulated strains of H. influenzae in adults as well as children.

• Hib vaccine, consisting of type b capsular carbohydrate conjugated to diphtheria toxoid protein, as part of childhood immunization schedule

a. The Hib vaccine is so successful that it has practically eliminated H. influenza B from pediatrics.

• Prompt treatment with a broad-spectrum β-lactamase–resistant cephalosporin (e.g., ceftriaxone) for serious infections

1. Slender, gram-negative, facultatively intracellular, pleomorphic coccobacillus

2. Poorly staining with Gram stain

3. Cysteine and iron salts required for growth

4. Usually cultured on supplemented BCYE agar (buffered charcoal yeast extract agar)

1. Intracellular infection is established in alveolar macrophages and monocytes following inhalation of legionellae.

• Coating of bacteria with C3b promotes their phagocytosis by macrophages.

• Inhibition of phagolysosome fusion by legionellae protects them against intracellular killing in macrophages.

2. Degradative enzymes produced by bacteria eventually kill infected cells.

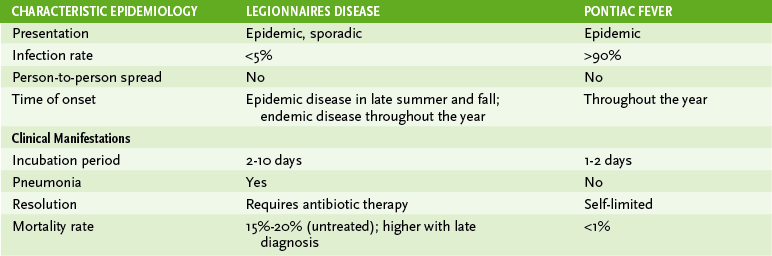

C Diseases caused by L. pneumophila (Table 12-2)

1. Water sources (e.g., air-conditioning cooling towers, mist, condensers, and water systems; and lakes and streams) are natural reservoirs of legionellae.