395 |

Gout and Other Crystal-Associated Arthropathies |

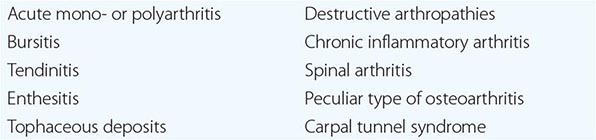

The use of polarizing light microscopy during synovial fluid analysis in 1961 by McCarty and Hollander and the subsequent application of other crystallographic techniques, such as electron microscopy, energy-dispersive elemental analysis, and x-ray diffraction, have allowed investigators to identify the roles of different microcrystals, including monosodium urate (MSU), calcium pyrophosphate (CPP), calcium apatite (apatite), and calcium oxalate (CaOx), in inducing acute or chronic arthritis or periarthritis. The clinical events that result from deposition of MSU, CPP, apatite, and CaOx have many similarities but also have important differences. Because of often similar clinical presentations, the need to perform synovial fluid analysis to distinguish the type of crystal involved must be emphasized. Polarized light microscopy alone can identify most typical crystals; apatite, however, is an exception. Aspiration and analysis of effusions are also important to assess the possibility of infection. Apart from the identification of specific microcrystalline materials or organisms, synovial fluid characteristics in crystal-associated diseases are nonspecific, and synovial fluid can be inflammatory or noninflammatory. Without crystal identification, these diseases can be confused with rheumatoid or other types of arthritis. A list of possible musculoskeletal manifestations of crystal-associated arthritis is shown in Table 395-1.

|

MUSCULOSKELETAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CRYSTAL-INDUCED ARTHRITIS |

GOUT

Gout is a metabolic disease that most often affects middle-aged to elderly men and postmenopausal women. It results from an increased body pool of urate with hyperuricemia. It typically is characterized by episodic acute arthritis or chronic arthritis caused by deposition of MSU crystals in joints and connective tissue tophi and the risk for deposition in kidney interstitium or uric acid nephrolithiasis (Chap. 431e).

ACUTE AND CHRONIC ARTHRITIS

Acute arthritis is the most common early clinical manifestation of gout. Usually, only one joint is affected initially, but polyarticular acute gout can occur in subsequent episodes. The metatarsophalangeal joint of the first toe often is involved, but tarsal joints, ankles, and knees also are affected commonly. Especially in elderly patients or in advanced disease, finger joints may be involved. Inflamed Heberden’s or Bouchard’s nodes may be a first manifestation of gouty arthritis. The first episode of acute gouty arthritis frequently begins at night with dramatic joint pain and swelling. Joints rapidly become warm, red, and tender, with a clinical appearance that often mimics that of cellulitis. Early attacks tend to subside spontaneously within 3–10 days, and most patients have intervals of varying length with no residual symptoms until the next episode. Several events may precipitate acute gouty arthritis: dietary excess, trauma, surgery, excessive ethanol ingestion, hypouricemic therapy, and serious medical illnesses such as myocardial infarction and stroke.

After many acute mono- or oligoarticular attacks, a proportion of gouty patients may present with a chronic nonsymmetric synovitis, causing potential confusion with rheumatoid arthritis (Chap. 380). Less commonly, chronic gouty arthritis will be the only manifestation, and, more rarely, the disease will manifest only as periarticular tophaceous deposits in the absence of synovitis. Women represent only 5–20% of all patients with gout. Most women with gouty arthritis are postmenopausal and elderly, have osteoarthritis and arterial hypertension that causes mild renal insufficiency, and usually are receiving diuretics. Premenopausal gout is rare. Kindreds of precocious gout in young females caused by decreased renal urate clearance and renal insufficiency have been described.

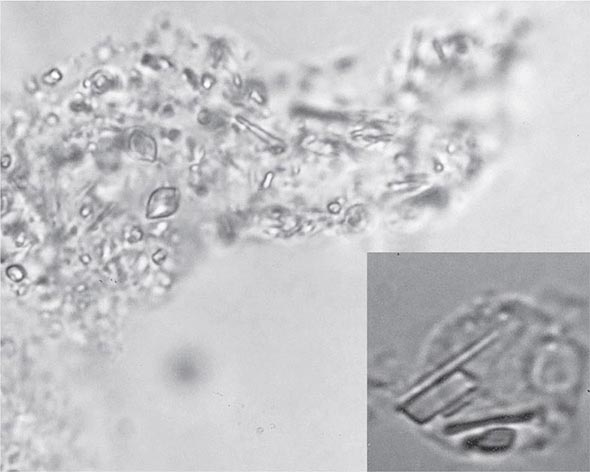

Laboratory Diagnosis Even if the clinical appearance strongly suggests gout, the presumptive diagnosis ideally should be confirmed by needle aspiration of acutely or chronically involved joints or tophaceous deposits. Acute septic arthritis, several of the other crystalline-associated arthropathies, palindromic rheumatism, and psoriatic arthritis may present with similar clinical features. During acute gouty attacks, needle-shaped MSU crystals typically are seen both intracellularly and extracellularly (Fig. 395-1). With compensated polarized light, these crystals are brightly birefringent with negative elongation. Synovial fluid leukocyte counts are elevated from 2000 to 60,000/μL. Effusions appear cloudy due to the increased numbers of leukocytes. Large amounts of crystals occasionally produce a thick pasty or chalky joint fluid. Bacterial infection can coexist with urate crystals in synovial fluid; if there is any suspicion of septic arthritis, joint fluid must be cultured.

FIGURE 395-1 Extracellular and intracellular monosodium urate crystals, as seen in a fresh preparation of synovial fluid, illustrate needle-and rod-shaped crystals. These crystals are strongly negative birefringent crystals under compensated polarized light microscopy; 400×.

MSU crystals also can often be demonstrated in the first metatarsophalangeal joint and in knees not acutely involved with gout. Arthrocentesis of these joints is a useful technique to establish the diagnosis of gout between attacks.

Serum uric acid levels can be normal or low at the time of an acute attack, as inflammatory cytokines can be uricosuric and effective initiation of hypouricemic therapy can precipitate attacks. This limits the value of serum uric acid determinations for the diagnosis of gout. Nevertheless, serum urate levels are almost always elevated at some time and are important to use to follow the course of hypouricemic therapy. A 24-h urine collection for uric acid can, in some cases, be useful in assessing the risk of stones, elucidating overproduction or underexcretion of uric acid, and deciding whether it may be appropriate to use a uricosuric therapy (Chap. 431e). Excretion of >800 mg of uric acid per 24 h on a regular diet suggests that causes of overproduction of purine should be considered. Urinalysis, serum creatinine, hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC) count, liver function tests, and serum lipids should be obtained because of possible pathologic sequelae of gout and other associated diseases requiring treatment and as baselines because of possible adverse effects of gout treatment.

Radiographic Features Cystic changes, well-defined erosions with sclerotic margins (often with overhanging bony edges), and soft tissue masses are characteristic radiographic features of advanced chronic tophaceous gout. Ultrasound may aid earlier diagnosis by showing a double contour sign overlying the articular cartilage. Dual-energy computed tomography (CT) can show specific features establishing the presence of urate crystals.

CALCIUM PYROPHOSPHATE DEPOSITION (CPPD) DISEASE

PATHOGENESIS

The deposition of CPP crystals in articular tissues is most common in the elderly, occurring in 10–15% of persons age 65–75 years and 30–50% of those >85 years. In most cases, this process is asymptomatic and the cause of CPPD is uncertain. Because >80% of patients are >60 years and 70% have preexisting joint damage from other conditions, it is likely that biochemical changes in aging or diseased cartilage favor crystal nucleation. In patients with CPPD arthritis, there is increased production of inorganic pyrophosphate and decreased levels of pyrophosphatases in cartilage extracts. Mutations in the ANKH gene, as described in both familial and sporadic cases, can increase elaboration and extracellular transport of pyrophosphate. The increase in pyrophosphate production appears to be related to enhanced activity of ATP pyrophosphohydrolase and 5′-nucleotidase, which catalyze the reaction of ATP to adenosine and pyrophosphate. This pyrophosphate could combine with calcium to form CPP crystals in matrix vesicles or on collagen fibers. There are decreased levels of cartilage glycosaminoglycans that normally inhibit and regulate crystal nucleation. High activities of transglutaminase enzymes also may contribute to the deposition of CPP crystals.

Release of CPP crystals into the joint space is followed by the phagocytosis of those crystals by monocyte-macrophages and neutrophils, which respond by releasing chemotactic and inflammatory substances and, as with MSU crystals, activating the inflammasome.

A minority of patients with CPPD arthropathy have metabolic abnormalities or hereditary CPP disease (Table 395-2). These associations suggest that a variety of different metabolic products may enhance CPP crystal deposition either by directly altering cartilage or by inhibiting inorganic pyrophosphatases. Included among these conditions are hyperparathyroidism, hemochromatosis, hypophosphatasia, hypomagnesemia, and possibly myxedema. The presence of CPPD arthritis in individuals <50 years old should lead to consideration of these metabolic disorders (Table 395-2) and inherited forms of disease, including those identified in a variety of ethnic groups. Genomic DNA studies performed on different kindreds have shown a possible location of genetic defects on chromosome 8q or on chromosome 5p in a region that expresses the gene of the membrane pyrophosphate channel (ANKH gene). As noted above, mutations described in the ANKH gene in kindreds with CPPD arthritis can increase extracellular pyrophosphate and induce CPP crystal formation. Investigation of younger patients with CPPD should include inquiry for evidence of familial aggregation and evaluation of serum calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, magnesium, iron, and transferrin.

|

CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH CALCIUM PYROPHOSPHATE CRYSTAL DEPOSITION DISEASE |

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CPPD arthropathy may be asymptomatic, acute, subacute, or chronic or may cause acute synovitis superimposed on chronically involved joints. Acute CPPD arthritis originally was termed pseudogout by McCarty and co-workers because of its striking similarity to gout. Other clinical manifestations of CPPD include (1) association with or enhancement of peculiar forms of osteoarthritis; (2) induction of severe destructive disease that may radiographically mimic neuropathic arthritis; (3) production of chronic symmetric synovitis that is clinically similar to rheumatoid arthritis; (4) intervertebral disk and ligament calcification with restriction of spine mobility, the crowned dens syndrome, or spinal stenosis (most commonly seen in the elderly); and (5) rarely periarticular tophus-like nodules.

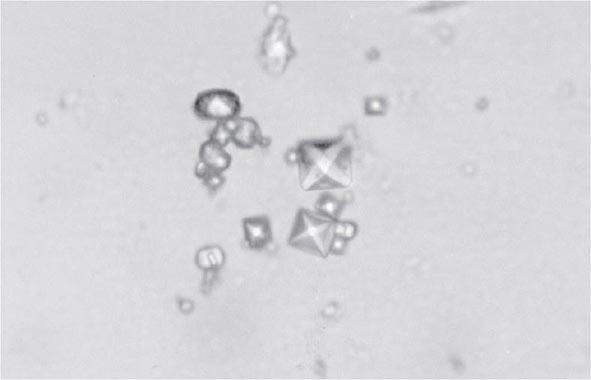

The knee is the joint most frequently affected in CPPD arthropathy. Other sites include the wrist, shoulder, ankle, elbow, and hands. The temporomandibular joint may be involved. Clinical and radiographic evidence indicates that CPPD deposition is polyarticular in at least two-thirds of patients. When the clinical picture resembles that of slowly progressive osteoarthritis, diagnosis may be difficult. Joint distribution may provide important clues suggesting CPPD disease. For example, primary osteoarthritis less often involves metacarpophalangeal, wrist, elbow, shoulder, or ankle joints. If radiographs or ultrasound reveal punctate and/or linear radiodense deposits within fibrocartilaginous joint menisci or articular hyaline cartilage (chondrocalcinosis), the diagnostic likelihood of CPPD disease is further increased. Definitive diagnosis requires demonstration of typical rhomboid or rodlike crystals (generally weakly positively birefringent or nonbirefringent with polarized light) in synovial fluid or articular tissue (Fig. 395-2). In the absence of joint effusion or indications to obtain a synovial biopsy, chondrocalcinosis is presumptive of CPPD. One exception is chondrocalcinosis due to CaOx in some patients with chronic renal failure.

FIGURE 395-2 Intracellular and extracellular calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystals, as seen in a fresh preparation of synovial fluid, illustrate rectangular, rod-shaped, and rhomboid crystals that are weakly positively or nonbirefringent crystals (compensated polarized light microscopy; 400×).

Acute attacks of CPPD arthritis may be precipitated by trauma. Rapid diminution of serum calcium concentration, as may occur in severe medical illness or after surgery (especially parathyroidectomy), can also lead to attacks.

In as many as 50% of cases, episodes of CPPD-induced inflammation are associated with low-grade fever and, on occasion, temperatures as high as 40°C (104°F). In such cases, synovial fluid analysis with microbial cultures is essential to rule out the possibility of infection. In fact, infection in a joint with any microcrystalline deposition process can lead to crystal shedding and subsequent synovitis from both crystals and microorganisms. The leukocyte count in synovial fluid in acute CPPD can range from several thousand cells to 100,000 cells/μL, with the mean being about 24,000 cells/μL and the predominant cell being the neutrophil. CPP crystals may be seen inside tissue fragments and fibrin clots and in neutrophils (Fig. 395-2). CPP crystals may coexist with MSU and apatite in some cases.

CALCIUM APATITE DEPOSITION DISEASE

PATHOGENESIS

Apatite is the primary mineral of normal bone and teeth. Abnormal accumulation of basic calcium phosphates, largely carbonate substituted apatite, can occur in areas of tissue damage (dystrophic calcification), hypercalcemic or hyperparathyroid states (metastatic calcification), and certain conditions of unknown cause (Table 395-3). In chronic renal failure, hyperphosphatemia can contribute to extensive apatite deposition both in and around joints. Familial aggregation is rarely seen; no association with ANKH mutations has been described thus far. Apatite crystals are deposited primarily on matrix vessels. Incompletely understood alterations in matrix proteoglycans, phosphatases, hormones, and cytokines probably can influence crystal formation.

|

CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH APATITE DEPOSITION DISEASE |

Abbreviation: SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Apatite aggregates are commonly present in synovial fluid in an extremely destructive chronic arthropathy of the elderly that occurs most often in the shoulders (Milwaukee shoulder) and in a similar process in hips, knees, and erosive osteoarthritis of fingers. Joint destruction is associated with damage to cartilage and supporting structures, leading to instability and deformity. Progression tends to be indolent. Symptoms range from minimal to severe pain and disability that may lead to joint replacement surgery. Whether severely affected patients represent an extreme synovial tissue response to the apatite crystals that are so common in osteoarthritis is uncertain. Synovial lining cell or fibroblast cultures exposed to apatite (or CPP) crystals can undergo mitosis and markedly increase the release of prostaglandin E2, various cytokines, and also collagenases and neutral proteases, underscoring the destructive potential of abnormally stimulated synovial lining cells.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Periarticular or articular deposits may occur and may be associated with acute reversible inflammation and/or chronic damage to the joint capsule, tendons, bursa, or articular surfaces. The most common sites of apatite deposition include bursae and tendons in and/or around the knees, shoulders, hips, and fingers. Clinical manifestations include asymptomatic radiographic abnormalities, acute synovitis, bursitis, tendinitis, and chronic destructive arthropathy. Although the true incidence of apatite arthritis is not known, 30–50% of patients with osteoarthritis have apatite microcrystals in their synovial fluid. Such crystals frequently can be identified in clinically stable osteoarthritic joints, but they are more likely to come to attention in persons experiencing acute or subacute worsening of joint pain and swelling. The synovial fluid leukocyte count in apatite arthritis is usually low (<2000/μL) despite dramatic symptoms, with predominance of mononuclear cells.

DIAGNOSIS

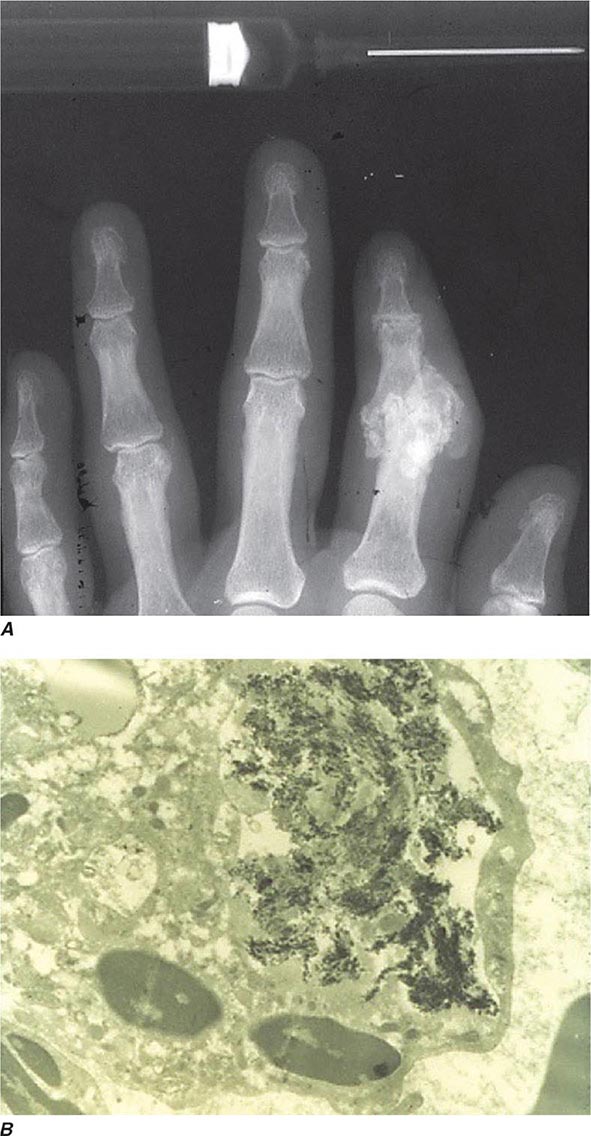

Intra- and/or periarticular calcifications with or without erosive, destructive, or hypertrophic changes may be seen on radiographs (Fig. 395-3). They should be distinguished from the linear calcifications typical of CPPD.

FIGURE 395-3 A. Radiograph showing calcification due to apatite crystals surrounding an eroded joint. B. An electron micrograph demonstrates dark needle-shaped apatite crystals within a vacuole of a synovial fluid mononuclear cell (30,000×).

Definitive diagnosis of apatite arthropathy, also called basic calcium phosphate disease, depends on identification of crystals from synovial fluid or tissue (Fig. 395-3). Individual crystals are very small and can be seen only by electron microscopy. Clumps of crystals may appear as 1- to 20-μm shiny intra- or extracellular nonbirefringent globules or aggregates that stain purplish with Wright’s stain and bright red with alizarin red S. Tetracycline binding and other investigative techniques are under consideration as labeling alternatives. Absolute identification depends on electron microscopy with energy-dispersive elemental analysis, x-ray diffraction, infrared spectroscopy, or Raman microspectroscopy, but these techniques usually are not required in clinical diagnosis.

CAOX DEPOSITION DISEASE

PATHOGENESIS

Primary oxalosis is a rare hereditary metabolic disorder (Chap. 434e). Enhanced production of oxalic acid may result from at least two different enzyme defects, leading to hyperoxalemia and deposition of CaOx crystals in tissues. Nephrocalcinosis and renal failure are typical results. Acute and/or chronic CaOx arthritis, periarthritis, and bone disease may complicate primary oxalosis during later years of illness.

Secondary oxalosis is more common than the primary disorder. In chronic renal disease, calcium oxalate deposits have long been recognized in visceral organs, blood vessels, bones, and cartilage and are now known to be one of the causes of arthritis in chronic renal failure. Thus far, reported patients have been dependent on long-term hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis (Chap. 336), and many had received ascorbic acid supplements. Ascorbic acid is metabolized to oxalate, which is inadequately cleared in uremia and by dialysis. Such supplements and foods high in oxalate content usually are avoided in dialysis programs because of the risk of enhancing hyperoxalosis and its sequelae.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS

CaOx aggregates can be found in bone, articular cartilage, synovium, and periarticular tissues. From these sites, crystals may be shed, causing acute synovitis. Persistent aggregates of CaOx can, like apatite and CPP, stimulate synovial cell proliferation and enzyme release, resulting in progressive articular destruction. Deposits have been documented in fingers, wrists, elbows, knees, ankles, and feet.

Clinical features of acute CaOx arthritis may not be distinguishable from those due to urate, CPP, or apatite. Radiographs may reveal chondrocalcinosis or soft tissue calcifications. CaOx-induced synovial effusions are usually noninflammatory, with <2000 leukocytes/μL, or mildly inflammatory. Neutrophils or mononuclear cells can predominate. CaOx crystals have a variable shape and variable birefringence to polarized light. The most easily recognized forms are bipyramidal, have strong birefringence (Fig. 395-4), and stain with alizarin red S.

FIGURE 395-4 Bipyramidal and small polymorphic calcium oxalate crystals from synovial fluid are a classic finding in calcium oxalate arthropathy (ordinary light microscopy; 400×).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This chapter has been revised for this and the previous two editions from an original version written by Antonio Reginato, MD, in earlier editions of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine.

396 |

Fibromyalgia |

DEFINITION

Fibromyalgia (FM) is characterized by chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain and tenderness. Although FM is defined primarily as a pain syndrome, patients also commonly report associated neuropsychological symptoms of fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, and depression. Patients with FM have an increased prevalence of other syndromes associated with pain and fatigue, including chronic fatigue syndrome (Chap. 464e), temporomandibular disorder, chronic headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, and other pelvic pain syndromes. Available evidence implicates the central nervous system as key to maintaining pain and other core symptoms of FM and related conditions. The presence of FM is associated with substantial negative consequences for physical and social functioning.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

![]() In clinical settings, a diagnosis of FM is made in ∼2% of the population and is far more common in women than in men, with a ratio of ∼9:1. However, in population-based survey studies worldwide, the prevalence rate is ∼2–5%, with a female-to-male ratio of only 2–3:1 and with some variability depending on the method of ascertainment. The prevalence data are similar across socioeconomic classes. Cultural factors may play a role in determining whether patients with FM symptoms seek medical attention; however, even in cultures in which secondary gain is not expected to play a significant role, the prevalence of FM remains in this range.

In clinical settings, a diagnosis of FM is made in ∼2% of the population and is far more common in women than in men, with a ratio of ∼9:1. However, in population-based survey studies worldwide, the prevalence rate is ∼2–5%, with a female-to-male ratio of only 2–3:1 and with some variability depending on the method of ascertainment. The prevalence data are similar across socioeconomic classes. Cultural factors may play a role in determining whether patients with FM symptoms seek medical attention; however, even in cultures in which secondary gain is not expected to play a significant role, the prevalence of FM remains in this range.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pain and Tenderness At presentation, patients with FM most commonly report “pain all over.” These patients have pain that is typically both above and below the waist on both sides of the body and involves the axial skeleton (neck, back, or chest). The pain attributable to FM is poorly localized, difficult to ignore, severe in its intensity, and associated with a reduced functional capacity. For a diagnosis of FM, pain should have been present most of the day on most days for at least 3 months.

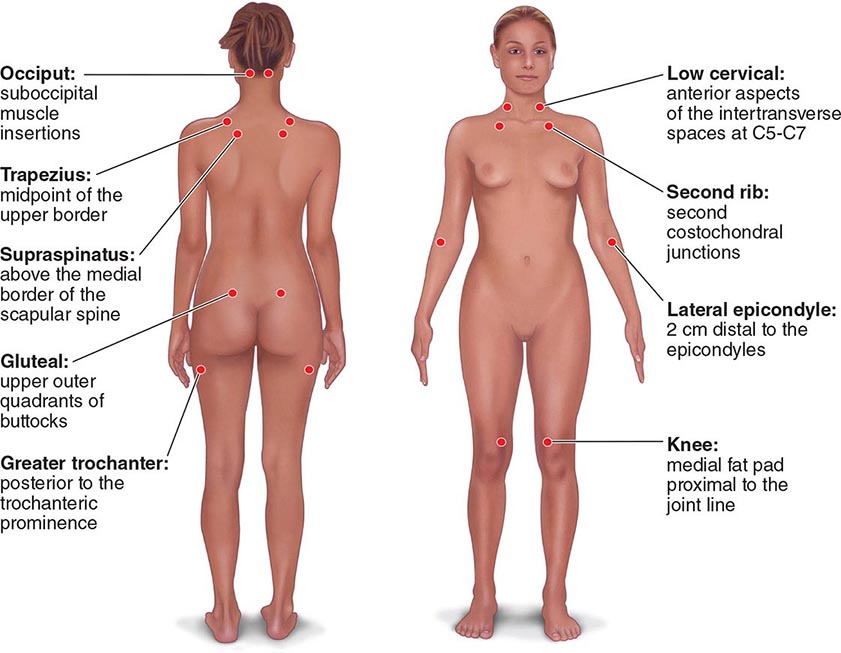

The clinical pain of FM is associated with increased evoked pain sensitivity. In clinical practice, this elevated sensitivity may be determined by a tender-point examination in which the examiner uses the thumbnail to exert pressure of ∼4 kg/m2 (or the amount of pressure leading to blanching of the tip of the thumbnail) on well-defined musculotendinous sites (Fig. 396-1). Previously, the classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology required that 11 of 18 sites be perceived as painful for a diagnosis of FM. In practice, tenderness is a continuous variable, and strict application of a categorical threshold for diagnostic specifics is not necessary. Newer criteria eliminate the need for tender points and focus instead on clinical symptoms of widespread pain and neuropsychological symptoms. The newer criteria perform well in a clinical setting in comparison to the older, tender-point criteria. However, it appears that when the new criteria are applied to populations, the result is an increase in prevalence of FM and a change in the sex ratio (see “Epidemiology,” earlier).

FIGURE 396-1 Tender-point assessment in patients with fibromyalgia. (Figure created using data from F Wolfe et al: Arthritis Care Res 62:600, 2010.)

Patients with FM often have peripheral pain generators that are thought to serve as triggers for the more widespread pain attributed to central nervous system factors. Potential pain generators such as arthritis, bursitis, tendinitis, neuropathies, and other inflammatory or degenerative conditions should be identified by history and physical examination. More subtle pain generators may include joint hypermobility and scoliosis. In addition, patients may have chronic myalgias triggered by infectious, metabolic, or psychiatric conditions that can also serve as triggers for the development of FM. These conditions are often identified in the differential diagnosis of patients with FM, and a major challenge is to distinguish the ongoing activity of a triggering condition from FM that is occurring as a consequence of a comorbid condition and that should itself be treated.

Neuropsychological Symptoms In addition to widespread pain, FM patients typically report fatigue, stiffness, sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, and depression. These symptoms are present to varying degrees in most FM patients but are not present in every patient or at all times in a given patient. Relative to pain, such symptoms may, however, have an equal or even greater impact on function and quality of life. Fatigue is highly prevalent in patients under primary care who ultimately are diagnosed with FM. Pain, stiffness, and fatigue often are worsened by exercise or unaccustomed activity (postexertional malaise). The sleep complaints include difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and early-morning awakening. Regardless of the specific complaint, patients awake feeling unrefreshed. Patients with FM may meet criteria for restless legs syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing; frank sleep apnea can also be documented. Cognitive issues are characterized as slowness in processing, difficulties with attention or concentration, problems with word retrieval, and short-term memory loss. Studies have demonstrated altered cognitive function in these domains in patients with FM, though speed of processing is age-appropriate. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are common, and the lifetime prevalence of mood disorders in patients with FM approaches 80%. Although depression is neither necessary nor sufficient for the diagnosis of FM, it is important to screen for major depressive disorders by querying for depressed mood and anhedonia. Analysis of genetic factors that are likely to predispose to FM reveals shared neurobiologic pathways with mood disorders, providing the basis for comorbidity (see later in this chapter).

Overlapping Syndromes Because FM can overlap in presentation with other chronic pain conditions, review of systems often reveals headaches, facial/jaw pain, regional myofascial pain particularly involving the neck or back, and arthritis. Visceral pain involving the gastrointestinal tract, bladder, and pelvic or perineal region is often present as well. Patients may or may not meet defined criteria for specific syndromes. It is important for patients to understand that shared pathways may mediate symptoms and that treatment strategies effective for one condition may help with global symptom management.

Comorbid Conditions FM is often comorbid with chronic musculoskeletal, infectious, metabolic, or psychiatric conditions. Whereas FM affects only 2–5% of the general population, it occurs in 20% or more of patients with degenerative or inflammatory rheumatic disorders, likely because these conditions serve as peripheral pain generators to alter central pain-processing pathways. Similarly, chronic infectious, metabolic, or psychiatric diseases associated with musculoskeletal pain can mimic FM and/or serve as a trigger for the development of FM. It is particularly important for clinicians to be sensitive to pain management of these comorbid conditions so that when FM emerges—characterized by pain outside the boundaries of what could reasonably be explained by the triggering condition, development of neuropsychological symptoms, or tenderness on physical examination—treatment of central pain processes will be undertaken as opposed to a continued focus on treatment of peripheral or inflammatory causes of pain.

Psychosocial Considerations Symptoms of FM often have their onset and are exacerbated during periods of high-level real or perceived stress. This pattern may reflect an interaction among central stress physiology, vigilance or anxiety, and central pain-processing pathways. An understanding of current psychosocial stressors will aid in patient management, as many factors that exacerbate symptoms cannot be addressed by pharmacologic approaches. Furthermore, there is a high prevalence of exposure to previous interpersonal and other forms of violence in patients with FM and related conditions. If posttraumatic stress disorder is an issue, the clinician should be aware of it and consider treatment options.

Functional Impairment It is crucial to evaluate the impact of FM symptoms on function and role fulfillment. In defining the success of a management strategy, improved function is a key measure. Functional assessment should include physical, mental, and social domains. A recognition of the ways in which role functioning falls short will be helpful in the establishment of treatment goals.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Because musculoskeletal pain is such a common complaint, the differential diagnosis of FM is broad. Table 396-1 lists some of the more common conditions that should be considered. Patients with inflammatory causes for widespread pain should be identifiable on the basis of specific history, physical findings, and laboratory or radiographic tests.

|

COMMON CONDITIONS IN THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF FIBROMYALGIA |

LABORATORY OR RADIOGRAPHIC TESTING

Routine laboratory and radiographic tests yield normal results in FM. Thus diagnostic testing is focused on exclusion of other diagnoses and evaluation for pain generators or comorbid conditions (Table 396-2). Most patients with new chronic widespread pain should be assessed for the most common entities in the differential diagnosis. Radiographic testing should be used sparingly and only for diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis. After the patient has been evaluated thoroughly, repeat testing is discouraged unless the symptom complex changes. Particularly to be discouraged is advanced imaging (MRI) of the spine unless there are features suggesting inflammatory spine disease or neurologic symptoms.

|

LABORATORY AND RADIOGRAPHIC TESTING IN PATIENTS WITH FIBROMYALGIA SYMPTOMS |

Source: LM Arnold et al: J Women’s Health 21:231, 2012; MA Fitzcharles et al: J Rheumatol 40:1388, 2013.

GENETICS AND PHYSIOLOGY

![]() As in most complex diseases, it is likely that a number of genes contribute to vulnerability to the development of FM. To date, these genes appear to be in pathways controlling pain and stress responses. Some of the genetic underpinnings of FM are shared across other chronic pain conditions. Genes associated with metabolism, transport, and receptors of serotonin and other monoamines have been implicated in FM and overlapping conditions. Genes associated with other pathways involved in pain transmission have also been described as vulnerability factors for FM. Taken together, the pathways in which polymorphisms have been identified in FM patients further implicate central factors in mediation of the physiology that leads to the clinical manifestations of FM.

As in most complex diseases, it is likely that a number of genes contribute to vulnerability to the development of FM. To date, these genes appear to be in pathways controlling pain and stress responses. Some of the genetic underpinnings of FM are shared across other chronic pain conditions. Genes associated with metabolism, transport, and receptors of serotonin and other monoamines have been implicated in FM and overlapping conditions. Genes associated with other pathways involved in pain transmission have also been described as vulnerability factors for FM. Taken together, the pathways in which polymorphisms have been identified in FM patients further implicate central factors in mediation of the physiology that leads to the clinical manifestations of FM.

Psychophysical testing of patients with FM has demonstrated altered sensory afferent pain processing and impaired descending noxious inhibitory control leading to hyperalgesia and allodynia. Functional MRI and other research imaging procedures clearly demonstrate activation of the brain regions involved in the experience of pain in response to stimuli that are innocuous in study participants without FM. Pain perception in FM patients is influenced by the emotional and cognitive dimensions, such as catastrophizing and perceptions of control, providing a solid basis for recommendations for cognitive and behavioral treatment strategies.

|

TREATMENT |

FIBROMYALGIA |

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Patients with chronic pain, fatigue, and other neuropsychological symptoms require a framework for understanding the symptoms that have such an important impact on their function and quality of life. Explaining the genetics, triggers, and physiology of FM can be an important adjunct in relieving associated anxiety and in reducing the overall cost of health care resources. In addition, patients must be educated regarding expectations for treatment. The physician should focus on improved function and quality of life rather than elimination of pain. Illness behaviors, such as frequent physician visits, should be discouraged and behaviors that focus on improved function strongly encouraged.

Treatment strategies should include physical conditioning, with encouragement to begin at low levels of aerobic exercise and to proceed with slow but consistent advancement. Patients who have been physically inactive or who report postexertional malaise may do best in supervised or water-based programs at the start. Activities that promote improved physical function with relaxation, such as yoga and Tai Chi, may also be helpful. Strength training may be recommended after patients reach their aerobic goals. Exercise programs are helpful in reducing tenderness and enhancing self-efficacy. Cognitive-behavioral strategies to improve sleep hygiene and reduce illness behaviors can also be helpful in management.

PHARMACOLOGIC APPROACHES

It is essential for the clinician to treat any comorbid triggering condition and to clearly delineate for the patient the treatment goals for each medication. For example, glucocorticoids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be useful for management of inflammatory triggers but are not effective against FM-related symptoms. At present, the treatment approaches that have proved most successful in FM patients target afferent or descending pain pathways. Table 396-3 lists the drugs with demonstrated effectiveness. It should be emphasized strongly that opioid analgesics are to be avoided in patients with FM. These agents have no demonstrated efficacy in FM and are associated with opioid-induced hyperalgesia that can worsen both symptoms and function. Use of single agents to treat multiple symptom domains is strongly encouraged. For example, if a patient’s symptom complex is dominated by pain and sleep disturbance, use of an agent that exerts both analgesic and sleep-promoting effects is desirable. These agents include sedating antidepressants such as amitriptyline and alpha-2-delta ligands such as gabapentin and pregabalin. For patients whose pain is associated with fatigue, anxiety, or depression, drugs that have both analgesic and antidepressant/anxiolytic effects, such as duloxetine or milnacipran, may be the best first choice.

|

PHARMACOLOGIC AGENTS EFFECTIVE FOR TREATMENT OF FIBROMYALGIA |

aRA Moore et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD008242, 2012. bApproved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. cW Hauser et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD010292, 2013.

Source: LM Arnold: Arthritis Rheum 56:1336, 2007.

397 |

Arthritis Associated with Systemic Disease, and Other Arthritides |

ARTHRITIS ASSOCIATED WITH SYSTEMIC DISEASE

ARTHROPATHY OF ACROMEGALY

Acromegaly is the result of excessive production of growth hormone by an adenoma in the anterior pituitary gland (Chap. 403). The excessive secretion of growth hormone along with insulin-like growth factor I stimulates proliferation of cartilage, periarticular connective tissue, and bone, resulting in several musculoskeletal problems, including osteoarthritis, back pain, muscle weakness, and carpal tunnel syndrome.

Osteoarthritis is a common feature, most often affecting the knees, shoulders, hips, and hands. Single or multiple joints may be affected. Hypertrophy of cartilage initially produces radiographic widening of the joint space. The newly synthesized cartilage is abnormally susceptible to fissuring, ulceration, and destruction. Ligamental laxity of joints further contributes to the development of osteoarthritis. Cartilage degrades, the joint space narrows, and subchondral sclerosis and osteophytes develop. Joint examination reveals crepitus and laxity. Joint fluid is noninflammatory. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals are found in the cartilage in some cases of acromegaly arthropathy and, when shed into the joint, can elicit attacks of pseudogout. Chondrocalcinosis may be observed on radiographs. Back pain is extremely common, perhaps as a result of spine hypermobility. Spine radiographs show normal or widened intervertebral disk spaces, hypertrophic anterior osteophytes, and ligamental calcification. The latter changes are similar to those observed in patients with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Dorsal kyphosis in conjunction with elongation of the ribs contributes to the development of the barrel chest seen in acromegalic patients. The hands and feet become enlarged as a result of soft tissue proliferation. The fingers are thickened and have spadelike distal tufts. One-third of patients have a thickened heel pad. Approximately 25% of patients exhibit Raynaud’s phenomenon. Carpal tunnel syndrome occurs in about half of patients. The median nerve is compressed by excess connective tissue in the carpal tunnel. Patients with acromegaly may develop proximal muscle weakness, which is thought to be caused by the effect of growth hormone on muscle. Serum muscle enzyme levels and electromyographic findings are normal. Muscle biopsy specimens contain muscle fibers of varying size without inflammation.

ARTHROPATHY OF HEMOCHROMATOSIS

Hemochromatosis is a disorder of iron storage. Absorption of excessive amounts of iron from the intestine leads to iron deposition in parenchymal cells, which results in impairment of organ function (Chap. 428). Symptoms of hemochromatosis usually begin between the ages of 40 and 60 but can appear earlier. Arthropathy, which occurs in 20–40% of patients, usually begins after the age of 50 and may be the first clinical feature of hemochromatosis. The arthropathy is an osteoarthritis-like disorder affecting the small joints of the hands and later the larger joints, such as knees, ankles, shoulders, and hips. The second and third metacarpophalangeal joints of both hands are often the first and most prominent joints affected; this clinical picture may provide an important clue to the possibility of hemochromatosis because these joints are not predominantly affected by “routine” osteoarthritis. Patients experience some morning stiffness and pain with use of involved joints. The affected joints are enlarged and mildly tender. Radiographs show narrowing of the joint space, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cysts, and juxtaarticular proliferation of bone. Hooklike osteophytes are seen in up to 20% of patients; although they are regarded as a characteristic feature of hemochromatosis, they can also occur in osteoarthritis and are not disease specific. The synovial fluid is noninflammatory. The synovium shows mild to moderate proliferation of iron-containing lining cells, fibrosis, and some mononuclear cell infiltration. In approximately half of patients, there is evidence of calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease, and some patients late in the course of disease experience episodes of acute pseudogout (Chap. 395). An early diagnosis is suggested by high serum transferrin saturation, which is more sensitive than ferritin elevation.

Iron may damage the articular cartilage in several ways. Iron catalyzes superoxide-dependent lipid peroxidation, which may play a role in joint damage. In animal models, ferric iron has been shown to interfere with collagen formation and increase the release of lysosomal enzymes from cells in the synovial membrane. Iron inhibits synovial tissue pyrophosphatase in vitro and therefore may inhibit pyrophosphatase in vivo, resulting in chondrocalcinosis.

HEMOPHILIC ARTHROPATHY

Hemophilia is a sex-linked recessive genetic disorder characterized by the absence or deficiency of factor VIII (hemophilia A, or classic hemophilia) or factor IX (hemophilia B, or Christmas disease) (Chap. 141). Hemophilia A constitutes 85% of cases. Spontaneous hemarthrosis is a common problem with both types of hemophilia and can lead to a deforming arthritis. The frequency and severity of hemarthrosis are related to the degree of clotting factor deficiency. Hemarthrosis is not common in other disorders of coagulation such as von Willebrand disease, factor V deficiency, warfarin therapy, or thrombocytopenia.

Hemarthrosis occurs after 1 year of age, when a child begins to walk and run. In order of frequency, the joints most commonly affected are the knees, ankles, elbows, shoulders, and hips. Small joints of the hands and feet are occasionally involved.

In the initial stage of arthropathy, hemarthrosis produces a warm, tensely swollen, and painful joint. The patient holds the affected joint in flexion and guards against any movement. Blood in the joint remains liquid because of the absence of intrinsic clotting factors and the absence of tissue thromboplastin in the synovium. The synovial blood is resorbed over a period of ≥1 week, with the precise interval depending on the size of the hemarthrosis. Joint function usually returns to normal or baseline in~2 weeks. Low-grade temperature elevation may accompany hemarthrosis, but a fever >101°F (38.3°C) warrants concern about infection.

Recurrent hemarthrosis may result in chronic arthritis. The involved joints remain swollen, and flexion deformities develop. Joint motion may be restricted and function severely limited. Restricted joint motion or laxity with subluxation is a feature of end-stage disease.

Bleeding into muscle and soft tissue also causes musculoskeletal dysfunction. When bleeding into the iliopsoas muscle occurs, the hip is held in flexion because of the pain, resulting in a hip flexion contracture. Rotation of the hip is preserved, which distinguishes this problem from hemarthrosis or other causes of hip synovitis. Expansion of the hematoma may place pressure on the femoral nerve, resulting in femoral neuropathy. Hemorrhage into a closed compartment space, such as the calf or the volar compartment in the forearm, can result in muscle necrosis, neuropathy, and flexion deformities of the ankles, wrists, and fingers. When bleeding involves periosteum or bone, a painful pseudotumor forms. These pseudotumors occur distal to the elbows or knees in children and improve with treatment of hemophilia. Surgical removal is indicated if the pseudotumor continues to enlarge. In adults, pseudotumors develop in the femur and pelvis and are usually refractory to treatment. When bleeding occurs in muscle, cysts may develop within the muscle. Needle aspiration of a cyst is contraindicated because this procedure can induce further bleeding; however, if the cyst becomes secondarily infected, drainage may be necessary (after factor repletion).

Septic arthritis is rare in hemophilia and is difficult to distinguish from acute hemarthrosis on physical examination. If there is serious suspicion of an infected joint, the joint should be aspirated immediately, the fluid cultured, and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics administered, with coverage for microorganisms including Staphylococcus, until culture results become available. Clotting-factor deficiency should be corrected before arthrocentesis to minimize the risk of traumatic bleeding.

Radiographs of joints reflect the stage of disease. In early stages, there is only capsule distention; later, juxtaarticular osteopenia, marginal erosions, and subchondral cysts develop. Late in the disease, the joint space is narrowed and there is bony overgrowth similar to that in osteoarthritis.

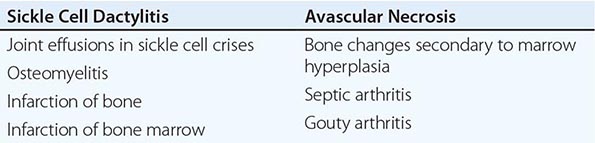

ARTHROPATHIES ASSOCIATED WITH HEMOGLOBINOPATHIES

Sickle Cell Disease Sickle cell disease (Chap. 127) is associated with several musculoskeletal abnormalities (Table 397-1). Children under the age of 5 years may develop diffuse swelling, tenderness, and warmth of the hands and feet lasting 1–3 weeks. This condition, referred to as sickle cell dactylitis or hand-foot syndrome, has also been observed in sickle cell thalassemia. Dactylitis is believed to result from infarction of the bone marrow and cortical bone leading to periostitis and soft tissue swelling. Radiographs show periosteal elevation, subperiosteal new-bone formation, and areas of radiolucency and increased density involving the metacarpals, metatarsals, and proximal phalanges. These bone changes disappear after several months. The syndrome leaves little or no residual damage. Because hematopoiesis ceases in the small bones of the hands and feet with age, the syndrome is rarely seen after age 5.

|

MUSCULOSKELETAL ABNORMALITIES IN SICKLE CELL DISEASE |

Sickle cell crisis is associated with periarticular pain and occasionally with joint effusions. The joint and periarticular area are warm and tender. Knees and elbows are most often affected, but other joints can be involved. Joint effusions are usually noninflammatory. Acute synovial infarction can cause a sterile effusion with high neutrophil counts in synovial fluid. Synovial biopsies have shown mild lining-cell proliferation and microvascular thrombosis with infarctions. Scintigraphic studies have shown decreased marrow uptake adjacent to the involved joint. The treatment for sickle cell crisis is detailed in Chap. 127.

Patients with sickle cell disease seem predisposed to osteomyelitis, which commonly involves the long tubular bones (Chap. 158); Salmonella is a particularly common cause (Chap. 190). Radiographs of the involved site initially show periosteal elevation, with subsequent disruption of the cortex. Treatment of the infection results in healing of the bone lesion. In addition, sickle cell disease is associated with bone infarction resulting from vaso-occlusion secondary to the sickling of red cells. Bone infarction also occurs in hemoglobin sickle cell disease and sickle cell thalassemia (Chap. 127). The bone pain in sickle cell crisis is due to infarction of bone and bone marrow. In children, infarction of the epiphyseal growth plate interferes with normal growth of the affected extremity. Radiographically, infarction of the bone cortex results in periosteal elevation and irregular thickening of the bone cortex. Infarction in the bone marrow leads to lysis, fibrosis, and new bone formation. Clinical distinction between osteomyelitis and bone infarctions can be difficult; imaging can be helpful.

Avascular necrosis of the head of the femur occurs in ~5% of patients. It also occurs in the humeral head and less commonly in the distal femur, tibial condyles, distal radius, vertebral bodies, and other juxtaarticular sites. Irregularity of the femoral head and other articular surfaces often results in degenerative joint disease. Radiography of the affected joint may show patchy radiolucency and density followed by flattening of the bone. MRI is a sensitive technique for detecting early avascular necrosis as well as bone infarction elsewhere. Total hip replacement and placement of prostheses in other joints may improve function and relieve joint pain in these patients.

Septic arthritis is occasionally encountered in sickle cell disease (Chap. 157). Multiple joints may be infected. Joint infection may result from bacteremia due to splenic dysfunction or from contiguous osteomyelitis. The more common microorganisms include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, and Salmonella. Salmonella does not cause septic arthritis as frequently as it causes osteomyelitis. Acute gouty arthritis is uncommon in sickle cell disease, even though 40% of patients are hyperuricemic. However, it may occur in patients generally not expected to get gout (young patients, female patients). Hyperuricemia is due to overproduction of uric acid secondary to increased red cell turnover as well as suboptimal renal excretion. Attacks may be polyarticular, and diagnostic arthrocentesis should be performed to distinguish infection from gout or synovial infarction.

The bone marrow hyperplasia in sickle cell disease results in widening of the medullary cavities, thinning of the cortices, and coarse trabeculations and central cupping of the vertebral bodies. These changes are also seen to a lesser degree in hemoglobin sickle cell disease and sickle cell thalassemia. In normal individuals red marrow is located mostly in the axial skeleton, but in sickle cell disease red marrow is found in the bones of the extremities and even in the tarsal and carpal bones. Vertebral compression may lead to dorsal kyphosis, and softening of the bone in the acetabulum may result in protrusio acetabuli.

Thalassemia A congenital disorder of hemoglobin synthesis, β thalassemia is characterized by impaired production of β chains (Chap. 127). Bone and joint abnormalities occur in β thalassemia, being most common in the major and intermedia groups. In one study, ~50% of patients with β thalassemia had evidence of symmetric ankle arthropathy characterized by a dull aching pain that was aggravated by weight bearing. The onset came most often in the second or third decade of life. The degree of ankle pain in these patients varied. Some patients experienced self-limited ankle pain that occurred only after strenuous physical activity and lasted several days or weeks. Other patients had chronic ankle pain that became worse with walking. Symptoms eventually abated in a few patients. Compression of the ankle, calcaneus, or forefoot was painful in some patients. Synovial fluid from two patients was noninflammatory. Radiographs of the ankle showed osteopenia, widened medullary spaces, thin cortices, and coarse trabeculations—findings that are largely the result of bone marrow expansion. The joint space was preserved. Specimens of bone from three patients revealed osteomalacia, osteopenia, and microfractures. Increased numbers of osteoblasts as well as increased foci of bone resorption were present on the bone surface. Iron staining was found in the bone trabeculae, in osteoid, and in the cement line. Synovium showed hyperplasia of lining cells, which contained deposits of hemosiderin. This arthropathy was considered to be related to the underlying bone pathology. The role of iron overload or abnormal bone metabolism in the pathogenesis of this arthropathy is not known. The arthropathy was treated with analgesics and splints. Patients also received transfusions to decrease hematopoiesis and bone marrow expansion.

In patients with β-thalassemia major and β-thalassemia intermedia, other joints are also involved, including the knees, hips, and shoulders. Acquired hemochromatosis with arthropathy has been described in a patient with thalassemia. Gouty arthritis and septic arthritis can occur. Avascular necrosis is not a feature of thalassemia because there is no sickling of red cells leading to thrombosis and infarction.

β-Thalassemia minor (also known as β-thalassemia trait) is likewise associated with joint manifestations. Chronic seronegative oligoarthritis affecting predominantly ankles, wrists, and elbows has been described; the affected patients had mild persistent synovitis without large effusions or joint erosions. Recurrent episodes of acute asymmetric arthritis have also been reported; episodes last <1 week and may affect the knees, ankles, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and metacarpal phalangeal joints. The mechanism underlying this arthropathy is unknown. Treatment with NSAIDs is not particularly effective.

MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH HYPERLIPIDEMIA

(See also Chap. 421) Musculoskeletal or cutaneous manifestations may be the first clinical indication of a specific hereditary disorder of lipoprotein metabolism. Patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (previously referred to as type II hyperlipoproteinemia) may have recurrent migratory polyarthritis involving the knees and other large peripheral joints and, to a lesser degree, peripheral small joints. Pain ranges from moderate to incapacitating. The involved joints can be warm, erythematous, swollen, and tender. Arthritis usually has a sudden onset, lasts from a few days to 2 weeks, and does not cause joint damage. Episodes may suggest acute gout attacks. Several attacks occur per year. Synovial fluid from involved joints is not inflammatory and contains few white cells and no crystals. Joint involvement may actually represent inflammatory periarthritis or peritendinitis and not true arthritis. The recurrent, transient nature of the arthritis may suggest rheumatic fever, especially because patients with hyperlipoproteinemia may have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and elevated antistreptolysin O titers (the latter being quite common). Attacks of tendinitis, including the large Achilles and patellar tendons, may come on gradually and last only a few days or may be acute as described above. Patients may be asymptomatic between attacks. Achilles tendinitis and other joint manifestations often precede the appearance of xanthomas and may be the first clinical indication of hyperlipoproteinemia. Attacks of tendinitis may follow treatment with a lipid-lowering drug. Over time, patients may develop tendinous xanthomas in the Achilles, patellar, and extensor tendons of the hands and feet. Xanthomas have also been reported in the peroneal tendon, the plantar aponeurosis, and the periosteum overlying the distal tibia. These xanthomas are located within tendon fibers. Tuberous xanthomas are soft subcutaneous masses located over the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, and hands as well as on the buttocks. They appear during childhood in homozygous patients and after the age of 30 in heterozygous patients. Patients with elevated plasma levels of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and triglycerides (previously referred to as type IV hyperlipoproteinemia) may also have a mild inflammatory arthritis affecting large and small peripheral joints, usually in an asymmetric pattern, with only a few joints involved at a time. The onset of arthritis usually comes in middle age. Arthritis may be persistent or recurrent, with episodes lasting a few days or weeks. Some patients may experience severe joint pain or morning stiffness. Joint tenderness and periarticular hyperesthesia may also be present, as may synovial thickening. Joint fluid is usually noninflammatory and without crystals but may have increased white blood cell counts with predominantly mononuclear cells. Radiographs may show juxtaarticular osteopenia and cystic lesions. Large bone cysts have been noted in a few patients. Xanthoma and bone cysts are also observed in other lipoprotein disorders. The pathogenesis of arthritis in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia or with elevated levels of VLDL and triglycerides is not well understood. NSAIDs or analgesics usually provide adequate relief of symptoms when used on an as-needed basis.

Patients may improve clinically as they are treated with lipid-lowering agents; however, patients treated with an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor may experience myalgias, and a few patients develop myopathy, myositis, or even rhabdomyolysis. Patients who develop myositis during statin therapy may be susceptible to this adverse effect because of an underlying muscle disorder and should be reevaluated after discontinuation of the drug. Myositis has also been reported with the use of niacin (Chap. 388) but is less common than myalgias.

Musculoskeletal syndromes have not clearly been associated with the more common mixed hyperlipidemias seen in general practice.

OTHER ARTHRITIDES

NEUROPATHIC JOINT DISEASE

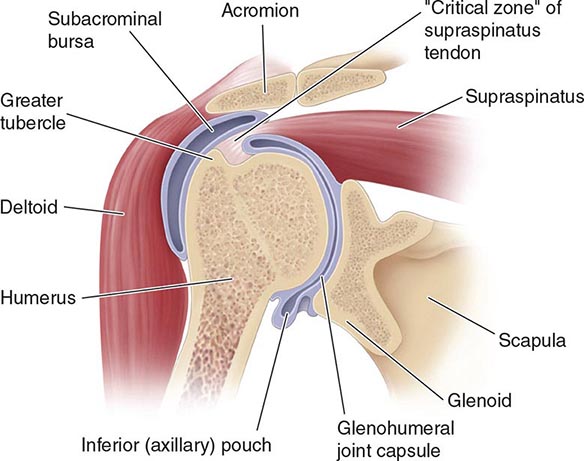

Neuropathic joint disease (Charcot joint) is a progressive destructive arthritis associated with loss of pain sensation, proprioception, or both. Normal muscular reflexes that modulate joint movement are impaired. Without these protective mechanisms, joints are subjected to repeated trauma, resulting in progressive cartilage and bone damage. Today, diabetes mellitus is the most frequent cause of neuropathic joint disease (Fig. 397-1). A variety of other disorders are associated with neuropathic arthritis, including tabes dorsalis, leprosy, yaws, syringomyelia, meningomyelocele, congenital indifference to pain, peroneal muscular atrophy (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease), and amyloidosis. An arthritis resembling neuropathic joint disease has been reported in patients who have received intraarticular glucocorticoid injections, but this is a rare complication and was not observed in one series of patients with knee osteoarthritis who received intraarticular glucocorticoid injections every 3 months for 2 years. The distribution of joint involvement depends on the underlying neurologic disorder (Table 397-2). In tabes dorsalis, the knees, hips, and ankles are most commonly affected; in syringomyelia, the glenohumeral joint, elbow, and wrist; and in diabetes mellitus, the tarsal and tarsometatarsal joints.

FIGURE 397-1 Charcot arthropathy associated with diabetes mellitus. Lateral foot radiograph demonstrating complete loss of the arch due to bony fragmentation and dislocation in the midfoot. (Courtesy of Andrew Neckers, MD, and Jean Schils, MD; with permission.)

|

DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH NEUROPATHIC JOINT DISEASE |

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathologic changes in the neuropathic joint are similar to those found in the severe osteoarthritic joint. There is fragmentation and eventual loss of articular cartilage with eburnation of the underlying bone. Osteophytes are found at the joint margins. With more advanced disease, erosions are present on the joint surface. Fractures, devitalized bone, intraarticular loose bodies, and microscopic fragments of cartilage and bone may be present.

At least two underlying mechanisms are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of neuropathic arthritis. An abnormal autonomic nervous system is thought to be responsible for the dysregulated blood flow to the joint with subsequent resorption of bone. Loss of bone, particularly in the diabetic foot, may be the initial finding. With the loss of deep pain, proprioception, and protective neuromuscular reflexes, the joint is subjected to repeated microtrauma, resulting in ligamental tears and bone fractures. The injury that follows frequent intraarticular glucocorticoid injections is thought to be due to the analgesic effect of glucocorticoids, leading to overuse of an already damaged joint; the result is accelerated cartilage damage, although steroid-induced cartilage damage be more common in some other animal species than in humans. It is not understood why only a few patients with neuropathy develop clinically evident neuropathic arthritis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Neuropathic joint disease usually begins in a single joint and then becomes apparent in other joints, depending on the underlying neurologic disorder. The involved joint becomes progressively enlarged as a result of bony overgrowth and synovial effusion. Loose bodies may be palpated in the joint cavity. Joint instability, subluxation, and crepitus occur as the disease progresses. Neuropathic joints may develop rapidly, and a totally disorganized joint with multiple bony fragments may evolve within weeks or months. The amount of pain experienced by the patient is less than would be anticipated from the degree of joint damage. Patients may experience sudden joint pain from intraarticular fractures of osteophytes or condyles.

Neuropathic arthritis is encountered most often in patients with diabetes mellitus, with an incidence of ~0.5%. The onset of disease usually comes at an age of ≥50 years in a patient who has had diabetes for several years, but exceptions occur. The tarsal and tarsometatarsal joints are most often affected, with the metatarsophalangeal and talotibial joints next most commonly involved. The knees and spine are occasionally involved. Patients often attribute the onset of foot pain to antecedent trauma such as twisting of the foot. Neuropathic changes may develop rapidly after a foot fracture or dislocation. The foot and ankle are often swollen. Downward collapse of the tarsal bones leads to convexity of the sole, referred to as a “rocker foot.” Large osteophytes may protrude from the top of the foot. Calluses frequently form over the metatarsal heads and may lead to infected ulcers and osteomyelitis. The value of protective inserts and orthotics, as well as regular foot examination, cannot be overstated. Radiographs may show resorption and tapering of the distal metatarsal bones. The term Lisfranc fracture-dislocation is sometimes used to describe the destructive changes at the tarsometatarsal joints.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of neuropathic arthritis is based on the clinical features and characteristic radiographic findings in a patient with underlying sensory neuropathy. The differential diagnosis of neuropathic arthritis depends upon the severity of the process and includes osteomyelitis, avascular necrosis, advanced osteoarthritis, stress fractures, and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Radiographs in neuropathic arthritis initially show changes of osteoarthritis with joint space narrowing, subchondral bone sclerosis, osteophytes, and joint effusions; marked destructive and hypertrophic changes follow later. The radiographic findings of neuropathic arthritis may be difficult to differentiate from those of osteomyelitis, especially in the diabetic foot. The joint margins in a neuropathic joint tend to be distinct, while in osteomyelitis they are blurred. Imaging studies may be helpful, but cultures of tissue from the joint are often required to exclude osteomyelitis. MRI and bone scans using indium 111–labeled white blood cells or indium 111–labeled immunoglobulin G, which will show increased uptake in osteomyelitis but not in a neuropathic joint, may be useful. A technetium bone scan will not distinguish osteomyelitis from neuropathic arthritis, as increased uptake is observed in both. The joint fluid in neuropathic arthritis is noninflammatory; may be xanthochromic or even bloody; and may contain fragments of synovium, cartilage, and bone. The finding of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals supports the diagnosis of crystal-associated arthropathy. In the absence of such crystals, an increased number of leukocytes may indicate osteomyelitis.

HYPERTROPHIC OSTEOARTHROPATHY AND CLUBBING

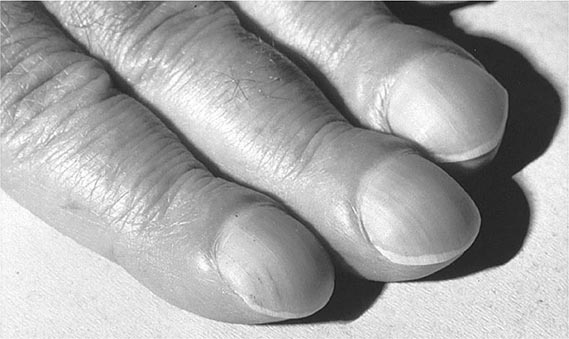

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) is characterized by clubbing of digits and, in more advanced stages, by periosteal new-bone formation and synovial effusions. HOA may be primary or familial and may begin in childhood. Secondary HOA is associated with intrathoracic malignancies, suppurative and some hypoxemic lung diseases, congenital heart disease, and a variety of other disorders. Clubbing is almost always a feature of HOA but can occur as an isolated manifestation (Fig. 397-2). The presence of clubbing in isolation may be congenital or represent either an early stage or one element in the spectrum of HOA. Isolated acquired clubbing has the same clinical significance as clubbing associated with periostitis.

FIGURE 397-2 Clubbing of the fingers. (Reprinted from the Clinical Slide Collection on the Rheumatic Diseases, © 1991, 1995. Used by permission of the American College of Rheumatology.)

Pathology and Pathophysiology of Acquired HOA In HOA, bone changes in the distal extremities begin as periostitis followed by new bone formation. At this stage, a radiolucent area may be observed between the new periosteal bone and the subjacent cortex. As the process progresses, multiple layers of new bone are deposited and become contiguous with the cortex, with consequent cortical thickening. The outer portion of the bone is laminated in appearance, with an irregular surface. Initially, the process of periosteal new-bone formation involves the proximal and distal diaphyses of the tibia, fibula, radius, and ulna and, less frequently, the femur, humerus, metacarpals, metatarsals, and phalanges. Occasionally, scapulae, clavicles, ribs, and pelvic bones are also affected. The adjacent interosseous membranes may become ossified. The distribution of bone manifestations is usually bilateral and symmetric. The soft tissue overlying the distal third of the arms and legs may be thickened. Proliferation of connective tissue occurs in the nail bed and volar pad of digits, giving the distal phalanges a clubbed appearance. Small blood vessels in the clubbed digits are dilated and have thickened walls. In addition, the number of arteriovenous anastomoses is increased.

Several theories have been suggested for the pathogenesis of HOA, but many have been disproved or have not explained the condition’s development in all clinical disorders with which it is associated. Previously proposed neurogenic and humoral theories are no longer considered likely explanations for HOA. Studies have suggested a role for platelets in the development of HOA. It has been observed that megakaryocytes and large platelet particles present in the venous circulation are fragmented in their passage through normal lung. In patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease and in other disorders associated with right-to-left shunts, these large platelet particles bypass the lung and reach the distal extremities, where they can interact with endothelial cells. Platelet–endothelial cell activation in the distal portion of the extremities may result in the release of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and other factors leading to the proliferation of connective tissue and periosteum. Stimulation of fibroblasts by PDGF and transforming growth factor β results in cell growth and collagen synthesis. Elevated plasma levels of von Willebrand factor antigen have been found in patients with both primary and secondary forms of HOA, indicating endothelial activation or damage. Abnormalities of collagen synthesis have been demonstrated in the involved skin of patients with primary HOA. Other factors are undoubtedly involved in the pathogenesis of HOA, and further studies are needed to elucidate this disorder.

Clinical Manifestations Primary or familial HOA, also referred to as pachydermoperiostitis or Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome, usually begins insidiously at puberty. In a smaller proportion of patients, the onset comes in the first year of life. The disorder is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with variable expression and is nine times more common among boys than among girls. Approximately one-third of patients have a family history of primary HOA.

Primary HOA is characterized by clubbing, periostitis, and unusual skin features. A small number of patients with this syndrome do not express clubbing. The skin changes and periostitis are prominent features of this syndrome. The skin becomes thickened and coarse. Deep nasolabial folds develop, and the forehead may become furrowed. Patients may have heavy-appearing eyelids and ptosis. The skin is often greasy, and there may be excessive sweating of the hands and feet. Patients may also experience acne vulgaris, seborrhea, and folliculitis. In a few patients, the skin over the scalp becomes very thick and corrugated, a feature that has been descriptively termed cutis verticis gyrata. The distal extremities, particularly the legs, become thickened as a consequence of the proliferation of new bone and soft tissue; when the process is extensive, the distal lower extremities resemble those of an elephant. The periostitis usually is not painful, which it can be in secondary HOA. Clubbing of the fingers may be extensive, producing large, bulbous deformities and clumsiness. Clubbing also affects the toes. Patients may experience articular and periarticular pain, especially in the ankles and knees, and joint motion may be mildly restricted by periarticular bone overgrowth. Noninflammatory effusions occur in the wrists, knees, and ankles. Synovial hypertrophy is not found. Associated abnormalities observed in patients with primary HOA include hypertrophic gastropathy, bone marrow failure, female escutcheon, gynecomastia, and cranial suture defects. In patients with primary HOA, the symptoms disappear when adulthood is reached.

HOA secondary to an underlying disease occurs more frequently than primary HOA. It accompanies a variety of disorders and may precede clinical features of the associated disorder by months. Clubbing is more frequent than the full syndrome of HOA in patients with associated illnesses. Because clubbing evolves over months and is usually asymptomatic, it is often recognized first by the physician and not the patient. Patients may experience a burning sensation in their fingertips. Clubbing is characterized by widening of the fingertips, enlargement of the distal volar pad, convexity of the nail contour, and the loss of the normal 15° angle between the proximal nail and cuticle. The thickness of the digit at the base of the nail is greater than the thickness at the distal interphalangeal joint. An objective measurement of finger clubbing can be made by determining the diameter at the base of the nail and at the distal interphalangeal joint of all 10 digits. Clubbing is present when the sum of the individual digit ratios is >10. At the bedside, clubbing can be appreciated by having the patient place the dorsal surface of the distal phalanges of the fourth fingers together with the nails opposing each other. Normally, an open area is visible between the bases of the opposing fingernails; when clubbing is present, this open space is no longer visible. The base of the nail feels spongy when compressed, and the nail can be easily rocked on its bed. When clubbing is advanced, the finger may have a drumstick appearance, and the distal interphalangeal joint can be hyperextended. Periosteal involvement in the distal extremities may produce a burning or deep-seated aching pain. The pain, which can be quite incapacitating, is aggravated by dependency and relieved by elevation of the affected limbs. Pressure applied over the distal forearms and legs or gentle percussion of distal long bones like the tibia may be quite painful.

Patients may experience joint pain, most often in the ankles, wrists, and knees. Joint effusions may be present; usually, they are small and noninflammatory. The small joints of the hands are rarely affected. Severe joint or long bone pain may be the presenting symptom of an underlying lung malignancy and may precede the appearance of clubbing. In addition, the progression of HOA tends to be more rapid when associated with malignancies, most notably bronchogenic carcinoma. Noninflammatory but variably painful knee effusions may occur prior to the appearance of clubbing and symptoms of distal periostitis. Unlike primary HOA, secondary HOA does not commonly include excessive sweating and oiliness of the skin or thickening of the facial skin.

HOA occurs in 5–10% of patients with intrathoracic malignancies, the most common being bronchogenic carcinoma and pleural tumors (Table 397-3). Lung metastases infrequently cause HOA. HOA is also seen in patients with intrathoracic infections, including lung abscesses, empyema, and bronchiectasis, but is uncommon in pulmonary tuberculosis. HOA may accompany chronic interstitial pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, and cystic fibrosis. In cystic fibrosis, clubbing is more common than the full syndrome of HOA. Other causes of clubbing include congenital heart disease with right-to-left shunts, bacterial endocarditis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, sprue, and neoplasms of the esophagus, liver, and small and large bowel. In patients who have congenital heart disease with right-to-left shunts, clubbing alone occurs more often than the full syndrome of HOA.

|

DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH HYPERTROPHIC OSTEOARTHROPATHY |

aUnilateral involvement. bBilateral lower-extremity involvement.

Unilateral clubbing has been found in association with aneurysms of major extremity arteries, with infected arterial grafts, and with arteriovenous fistulas of brachial vessels. Clubbing of the toes but not the fingers has been associated with an infected abdominal aortic aneurysm and patent ductus arteriosus. Clubbing of a single digit may follow trauma and has been reported in tophaceous gout and sarcoidosis. While clubbing occurs more commonly than the full syndrome in most diseases, periostitis in the absence of clubbing has been observed in the affected limb of patients with infected arterial grafts.

Hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease), treated or untreated, is occasionally associated with clubbing and periostitis of the bones of the hands and feet. This condition is referred to as thyroid acropachy. Periostitis may be asymptomatic and occurs in the midshaft and diaphyseal portion of the metacarpal and phalangeal bones. Significant hand-joint pain may occur; this pain may respond to successful therapy for thyroid dysfunction. The long bones of the extremities are seldom affected. Elevated levels of long-acting thyroid stimulator are found in the sera of these patients.

Laboratory Findings The laboratory abnormalities reflect the underlying disorder. The synovial fluid of involved joints has <500 white cells/μL, and the cells are predominantly mononuclear. Radiographs show a faint radiolucent line beneath the new periosteal bone along the shaft of long bones at their distal end. These changes are observed most frequently at the ankles, wrists, and knees. The ends of the distal phalanges may show osseous resorption. Radionuclide studies show pericortical linear uptake along the cortical margins of long bones that may precede any radiographic changes.

REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY SYNDROME

The reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome is now referred to as complex regional pain syndrome, type 1, according to the new classification system of the International Association for the Study of Pain. This syndrome is characterized by pain and swelling, usually of a distal extremity, accompanied by vasomotor instability, trophic skin changes, and the rapid development of bony demineralization. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome, including its treatment, is covered in greater detail in Chap. 454.

TIETZE SYNDROME AND COSTOCHONDRITIS

Tietze syndrome is manifested by painful swelling of one or more costochondral articulations. The age of onset is usually before 40, and both sexes are affected equally. In most patients, only one joint is involved, usually the second or third costochondral joint. The onset of anterior chest pain may be sudden or gradual. The pain may radiate to the arms or shoulders and is aggravated by sneezing, coughing, deep inspirations, or twisting motions of the chest. The term costochondritis is often used interchangeably with Tietze syndrome, but some workers restrict the former term to pain of the costochondral articulations without swelling. Costochondritis is observed in patients over age 40; tends to affect the third, fourth, and fifth costochondral joints; and occurs more often in women. Both syndromes may mimic cardiac or upper abdominal causes of pain. Rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and reactive arthritis may involve costochondral joints but are distinguished easily by their other clinical features. Other skeletal causes of anterior chest wall pain are xiphoidalgia and the slipping rib syndrome, which usually involves the tenth rib. Malignancies such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, plasma cell cytoma, and sarcoma can invade the ribs, thoracic spine, or chest wall and produce symptoms suggesting Tietze syndrome. Patients with osteomalacia may have significant rib pain, with or without documented microfractures. These conditions should be distinguishable by radiography, bone scanning, vitamin D measurement, or biopsy. Analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and local glucocorticoid injections usually relieve symptoms of costochondritis/Tietze syndrome. Care should be taken to avoid overdiagnosing these syndromes in patients with acute chest pain syndromes; many patients will be tender to overly vigorous palpation of the costochondral joints.

MYOFASCIAL PAIN SYNDROME