CHAPTER 3 GLYCAEMIC CONTROL

OVERVIEW

To achieve and maintain the targets (Table 3.1) of optimal glycaemic control can be difficult because of the progressive deterioration of pancreatic insulin secretion. Success is more likely if the patient, in collaboration with the professional and guided by monitoring of glycaemic control, masters the complex task of balancing the three key components of diet, physical activity and blood glucose-lowering medication dosage.

| Target | Who monitors | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Avoiding hypoglycaemia | Patient | Recognises warning signs |

| Balances regular meals, correct dose of therapy and physical activity | ||

| Able to correct promptly | ||

| Professional | Assesses needs and educates | |

| Fasting blood glucose of 4 to 7 mmol/l | Patient | Able to do and interpret tests |

| Adjusts therapy accordingly | ||

| Professional | Assesses needs and educates | |

| Glycated haemoglobin of less than 7.0%* | Patient | Understands significance of test result |

| Adjusts therapy accordingly | ||

| Professional | Repeats regularly | |

| Advises on appropriate therapy changes |

* Individualised HbA1c targets should be set between 6.5 and 7.5%; the lower value is preferred for patients at significant risk of vascular complications, the higher may be more appropriate for those with limited life expectancy or at risk of iatrogenic hypoglycaemia

This chapter discusses self-monitoring and blood glucose-lowering medication. Diet and physical activity are discussed in Chapter 2.

MONITORING

Glycaemic control can be assessed in three complementary ways:

GLYCOSYLATED HAEMOGLOBIN (OR FRUCTOSAMINE)

Glycosylated haemoglobin, or HbA1c, is formed by the non-enzymatic glycation of part of the β-chain of haemoglobin. HbA1c levels correlate to the mean plasma glucose over the preceding 9–10 weeks. The relationship between HbA1c and mean plasma glucose levels is shown in Table 3.2. A recent HbA1c result should normally be available at the full periodic review. HbA1c should be checked more frequently when control is poor or glycaemic management has been altered. The estimation of HbA1c requires expensive equipment and stringent quality control: it is generally not feasible in primary care and is best done by a hospital laboratory.

TABLE 3.2 Correlation between HbA1c level and mean plasma glucose levels (Rohlfing et al 2002)

| HbA1c (%) | Mean plasma glucose level (mmol/l) |

|---|---|

| 6 | 7.5 |

| 7 | 9.5 |

| 8 | 11.5 |

| 9 | 13.5 |

| 10 | 15.5 |

| 11 | 17.5 |

| 12 | 19.5 |

PATIENT SELF-MONITORING

Urine testing

Testing urine for the presence of glucose using test strips, such as Diabur-Test 5000, is non-invasive, inexpensive and may be preferred by patients who dislike blood testing, although there is some recent evidence that patients with type 2 diabetes can have negative perceptions about urine testing (Lawton 2004).

However, urine glucose testing has two main drawbacks:

Blood testing

Many varieties of finger-pricking lancets, blood glucose machines and test strips or sensors are now available, but only the lancets and strips/sensors can be prescribed on the NHS. Each different make of blood glucose machine has its own unique test strips. The current issue of the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS) lists each make of test strip and the machine(s) with which it is compatible. There have been significant technical advances in machines, with sensors allowing the blood drop to be analysed outside the machine. A rigorous evaluation of the different blood glucose meters and lancing devices now available on the UK market was published in 2005 by the Department of Health’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (details can be downloaded from its website, www.mhra.gov.uk). This useful source should assist in selecting the most suitable machine or device. Recently the MHRA has identified a safety problem with some blood glucose meters, where units of measurement may change and mislead the user.

Most official guidance and Diabetes UK advocate regular home blood glucose monitoring, even in type 2 diabetics, but there is not yet a clear consensus on how frequently to test. The latest ADA guidelines recommend 2 to 3 times daily in patients with type 1 diabetes, but possibly more often in patients with type 2 diabetes on insulin (ADA 2007). However, an editorial in the British Medical Journal challenged the conventional advice given about frequency of testing; it suggested that regular monitoring is not always necessary and that properly conducted large-scale studies need to be done to determine whether more frequent testing will improve glycaemic control (Reynolds 2004). It is sensible to test more frequently if control is poor or if the patient is unwell.

BLOOD GLUCOSE-LOWERING MEDICATION

A stepped approach to achieving and maintaining metabolic control is sensible. Starting with lifestyle changes and the early introduction of monotherapy, it moves progressively onto logical and effective combinations of different agents if the HbA1c remains greater than 7.0%. This is summarised in Table 3.3, with more than one option at some numbered steps, choice depending upon the clinical circumstances and patient preference (ADA 2007). It is the authors’ personal view that, in primary care, basal insulin is best introduced only when maximal oral therapy (including triple therapy, if feasible) cannot achieve good metabolic control.

TABLE 3.3 Summary of the stepped treatment of raised blood glucose in type 2 diabetes

| At each numbered step, letter “a” is first choice option, subject to drug contraindications, clinical circumstances and patient preference. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Step | Evaluation | Intervention |

| 1 | HbA1c <7.0% | Lifestyle advice (diet and physical activity) |

| 2a | ||

* Of the two glitazones, only pioglitazone currently has a licence to be prescribed in combination with insulin.

INSULIN SECRETAGOGUES (DRUGS THAT IMPROVE INSULIN SECRETION)

Currently, there are two main groups of drugs that increase insulin secretion:

NICE’s Clinical Guidelines in 2002 recommended that “a generic sulphonylurea should normally be the insulin secretagogue of choice” (NICE 2002).

Sulphonylureas

The different sulphonylureas appear to have a comparable effect upon blood glucose-lowering, but with different durations of action. Although both once-daily and twice-daily dosing are associated with better concordance, once-daily preparations have the advantages of reducing the total number of tablets that a patient needs to take and of potentially simplifying the drug regimen.

The two main drawbacks associated with sulphonylureas are that they can induce hypoglycaemia and can encourage weight gain. Glibenclamide is associated with the rare but potentially fatal occurrence of nocturnal hypoglycaemia in the elderly. Weight gain was recorded with both chlorpropamide and glibenclamide (but less than with insulin) in the intensively treated group of patients in the UKPDS (UKPDS 1998). However, hypoglycaemia and weight gain are not inevitable with sulphonylureas, and the risks of either occurring may be minimised by:

DRUGS THAT IMPROVE INSULIN ACTION

Biguanides

Metformin’s main side-effects are on the gastrointestinal tract; these can be minimised by a stepped approach to increasing the dose and by the medication being taken with or after food. Strict adherence to all the published contraindications, related to a perceived increased risk of precipitating lactic acidosis is not supported by systemic reviews (Salpeter et al 2002), and would result in metformin being prescribed only rarely, despite its undoubted value to many patients.

There is a slight risk of precipitating lactic acidosis with metformin in vulnerable individuals. Specific contraindications and guidelines for withdrawing metformin now include (Jones et al 2003, modified by authors):

As this guidance was published before the Renal NSF, clinicians may need to revisit the definition given above for renal impairment. It is reasonable to reduce metformin dose if the eGFR is < 60 ml/min and to stop metformin if the eGFR is < 45 ml/min, but any decision must balance the benefits against the risks. Metformin is contraindicated in people with heart failure; however, it has been suggested recently that metformin may not only be safe, but may potentially improve clinical outcomes (Eurich et al 2005). Further studies are required to clarify this issue.

Glitazones or thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

These are also known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) agonists (Krentz et al 2000). They act by promoting glucose utilisation peripherally, which enhances insulin action, but does not affect insulin secretion. Glitazones are thought to activate nuclear receptors, located mainly in adipose tissue, that affect glucose and lipid metabolism, and to maintain insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells (Day 1999) by reducing the effect of glucose “toxicity”. Once initiated, it may take 6–10 weeks for glitazones to work fully.

The two currently available glitazones, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, were launched in the UK in 2000. Troglitazone was launched in the UK in October 1997 and voluntarily withdrawn by its manufacturers weeks later, following reports of serious hepatic reactions worldwide. Current evidence suggests that neither rosiglitazone nor pioglitazone are hepatotoxic, but liver function should be monitored. These drugs are licensed as monotherapy, in combination with either metformin OR a sulphonylurea, or in triple therapy with metformin AND a sulphonylurea (only rosiglitazone is licensed for triple therapy). Their current UK licence does not include prescribing in combination with meglitinide analogues, but pioglitazone can now be prescribed in combination insulin. When compared with placebo, both glitazones significantly reduced HbA1c levels, either as monotherapy or in combination with other anti-diabetic agents (Chiquette et al 2004). Glitazones can cause weight gain, in part through fluid retention, which may precipitate heart failure, particularly if a glitazone is combined with insulin. Recently there have been reports of a rare association between glitazones and the development of macular oedema.

The use of these agents has been the subject of debate and evolving guidance, possibly in part because both glitazones are very expensive when compared to metformin or to most sulphonylureas and because of ongoing uncertainty about their effect on outcomes. The NICE Appraisal Committee issued guidance first in 2000/1, then updated in August 2003 on the use of both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone within their current UK licences. NICE recommends their use mainly in those unable to take metformin and a sulphonylurea in combination because of lack of tolerance or a contraindication to one of these drugs (NICE Appraisal Committee 2003). However, in September 2003 the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal products (EMEA) extended the licence of glitazones as preferred second-line drugs in addition to metformin in obese patients (Bailey et al 2003).

In 2004, the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) produced a position statement that included the following recommendations for patients with type 2 diabetes (Higgs et al 2004):

In obese type 2 patients (particularly from some ethnic groups), insulin resistance is likely to be significant. This needs to be tackled by a combination of nonpharmacological (improving diet and levels of physical activity) and pharmacological interventions. If monotherapy with metformin fails to achieve adequate glycaemic control, then, as the next step, a metformin–glitazone combination may be preferred to a metformin–sulphonylurea combination, since sulphonylureas do not reduce insulin resistance.

In assessing the effect of glitazones on cardiovascular risk factors, a meta-analysis found that pioglitazone had a better effect than rosiglitazone on lipids (rosiglitazone increased LDL-C and total cholesterol and had no effect on TG levels; pioglitazone had no effect on LDL-C or total cholesterol and lowered TG levels), although both significantly increased HDL-C. No significant differences were shown between rosiglitazone and placebo in changes to systolic or diastolic blood pressure. Both glitazones are associated with weight gain (Chiquette et al 2004).

Looking at “hard” cardiovascular outcomes:

There are two studies involving rosiglitazone:

Are clinicians too preoccupied with achieving and maintaining tight glycaemic control? Should the reduction of cardiovascular risk be the priority over optimising glycaemic control? It is worth noting the advice of the National Prescribing Centre in January 2006: “… before pioglitazone is even considered, it would seem sensible to ensure that the use of hypertensives, statins, aspirin and metformin is optimised according to current guidelines.” (MeReC 2006).

INSULIN

Clinical indications for changing to insulin in type 2 diabetes

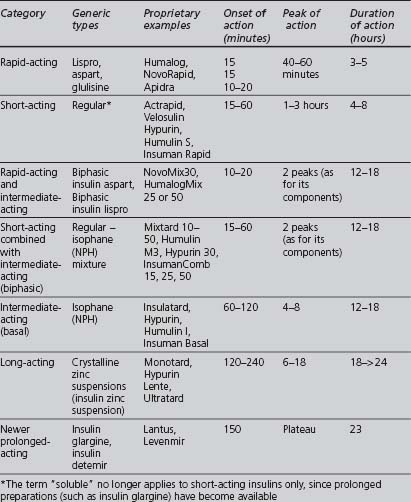

Insulin preparations

A wide variety of insulin preparations is currently available. Insulins can be classified according to their onset and duration of action, summarised in Table 3.4. They also vary according to their origin and method of manufacture (animal-derived, semisynthetic or synthetic), modifications that alter the duration of action, and their mode of delivery (e.g. syringe, pen, infusion device).

Onset and duration of action

Origin and method of manufacture

Short, intermediate- and long-acting insulins are either based on the human sequence of amino acids or extracted from an animal pancreas, usually porcine (less antigenic than beef), and then purified. Synthetic human insulin is produced either by enzyme modification of porcine insulin (emp) or, more commonly, from a proinsulin synthesised by bacteria (prb) or from a precursor synthesised by yeast (pyr). Human insulins have a more rapid onset and shorter duration of activity than porcine insulins (Krentz 2001).

Modifications that alter the onset and duration of action

Possible insulin regimens

Three regimens are commonly used:

Insulin dose adjustment

How to make the change to insulin

If the primary care team takes charge, an agreed and effective protocol should be followed. Success is possible: in one of the authors’ practice, the average HbA1c of the first 15 patients transferred onto insulin dropped from 9.7 to 6.9% (Curley, personal communication). Some innovatory teams have looked at a group approach, in which six to 10 patients can attend together, with the benefits of increased cost-effectiveness and of greater mutual support between often-anxious individuals in a similar situation.

In assessing the person who requires insulin, the following issues should be considered:

Key educational points for insulin conversion

Clear and correct advice on the following aspects of self-administering insulin should be given to patients, and suitable written literature should be made available for reference (Avery & Moore 1999).

Injection technique

The injection technique is as important as the type of insulin injected or the device used. The three key factors that influence insulin absorption are depth, site and technique (see Table 3.5):

TABLE 3.5 Guidance for choosing appropriate needle size and injection technique (Wilbourne 2002)

| Patient | Injection technique | Needle size (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Overweight adult | Pinch-up, 90° | 12.7 |

| No pinch-up, 45° | 12.7 | |

| No pinch-up | 8 | |

| Normal-weight adult | Pinch-up, 90° | 8 |

| Thin adult | No pinch-up, 90° | 5 or 6 |

| Children, adolescents | No pinch-up, 90° | 5 or 6 |

© John Wiley & Sons Ltd; reproduced with permission

Sites should be rotated and, for reliable absorption, different areas should not be used simultaneously. Injections should be spaced out within each area, moving one finger-breadth from the previous site:

Inhaled insulin

Not surprisingly, patient satisfaction for the use of inhaled insulin appears to be greater than for injected insulin, regardless of whether inhaled insulin was added to oral agents or subcutaneous insulin therapy (Capelleri 2002).

In December 2006 NICE published its guidance that “inhaled insulin is not recommended as a routine treatment for people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes” and should be a specialist (NICE 2006).

POSSIBLE FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS IN BLOOD GLUCOSE-LOWERING TREATMENT

Improving insulin release

Incretin mimetics

Two pharmaco-therapeutic approaches to exploit the actions of GLP-1 have been used:

These agents are called “gliptins”. They are taken orally and can be used in combination with metformin. Vildagliptin has been extensively investigated. Another compound is Sitagliptin. Both drugs improve glycaemic control. A third agent, Saxagliptin, has recently entered phase 3 clinical trials. Various other compounds are in different stages of development. The long-term safety (due to their complex and various actions) and precise clinical role are still not entirely clear.