Chapter 39 Gluteal contouring and rejuvenation

• Rates of surgical intervention to contour and rejuvenate the gluteal region have been rapidly increasing in recent years.

• The gluteal esthetic has largely been codified and varies across ethnicities.

• A systematic approach to the evaluation of the gluteal region is critical as one designs an appropriate and individualized operative plan.

• Modalities including the utilization of prosthetic implants, liposculpture and autologous tissue flaps may be employed alone or in combination to contour the gluteal region.

• These procedures may be performed safely and reliably if careful attention is paid to patient selection, operative design and technical execution.

• Complications of gluteal contouring procedures are generally infrequent and minor.

Introduction

Evaluation of female beauty and esthetics varies across cultures, but tends to focus on the breast and buttocks as key elements of investigation, evaluation and surgical intervention. Plastic surgical trends have largely focused on the breast; however, over the past 10 years augmentation and rejuvenation of the gluteal region have far outpaced intervention upon the breast and abdominal region. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgery trends, from 2000 to 2010, procedures which aim to enhance the esthetic of the gluteal region, including lower body lifting and specifically buttock lifting, have seen increases of 4550% and 143% respectively.1

Preoperative Preparation

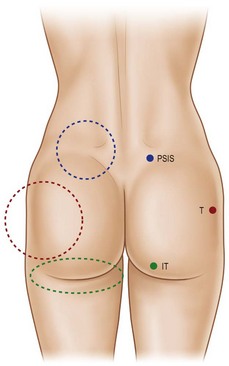

The characteristics of the ideal gluteal esthetic must first be defined prior to the determination of an appropriate surgical plan for the patient presenting for gluteal contouring surgery. The gluteal esthetic was largely codified in 2006 by Cuenca-Guerra and colleagues.2 Their analysis of over 2400 images of the gluteal area revealed four of the most recognizable characteristics of an esthetically pleasing gluteal region: (1) Two mild lateral depressions that correspond to the femoral greater trochanter; (2) A short infragluteal fold lying in the horizontal crease under the ischial tuberosity which does not extend beyond the medial two-thirds of the posterior thigh; (3) Two supragluteal fossettes (or dimples) on either side of the medial sacral crest which correspond to the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS); and (4) A V-shaped crease (sacral triangle) which arises from the proximal end of the gluteal crease and extends toward the sacral fossettes (Fig. 39.1).

It is critical for one to understand the variations across ethnicities in defining gluteal esthetics. Roberts has outlined very specific variations of this basic framework between ethnic groups in the United States.3 The short infragluteal fold, supragluteal fossettes and sacral triangle are generally universally accepted, whereas mild lateral depressions tend not to be preferred by Hispanic or African-Americans. This population tends to prefer a fuller lateral gluteal region along with increased projection compared to Asian-Americans, who prefer a short buttock with a high point of maximum projection. United States Caucasians tend to prefer a more athletic ideal with greater muscular and bony anatomy definition with less anterior-posterior projection.

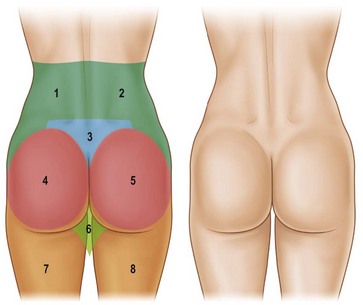

With these regions of a pleasing buttock region defined, one must have a systematic way to define the anatomy of the patient presenting for gluteal contouring. Centeno has described eight esthetic units that must be evaluated in order to design an appropriate, individualized surgical plan.4 From the posterior-anterior view, the gluteal region consists of two symmetrical flank units, a sacral triangle, two symmetrical gluteal units, two symmetrical thigh units, and one infragluteal diamond unit (Fig. 39.2). These regions should be individually considered and addressed in the surgical planning process. The junctions between these units serve as useful sites for incision placement during excisional procedures. Mendieta has subsequently divided these esthetic units into more discrete subunits.5 One must also consider the surrounding regions of the abdomen, anterior thigh, medial thigh, and lateral thigh. Derangement, overcorrection, or undercorrection of these areas may create overall disharmony as the gluteal region is surgically approached.

Proper evaluation of the gluteal region is critical when planning surgical intervention. Mendieta has devised a classification system analyzing the underlying bony framework, gluteus maximus muscle, subcutaneous fat topography and overlying skin to assist in operative planning.5 It is the interplay of these variables that assists in selecting the appropriate procedure on an individual basis.

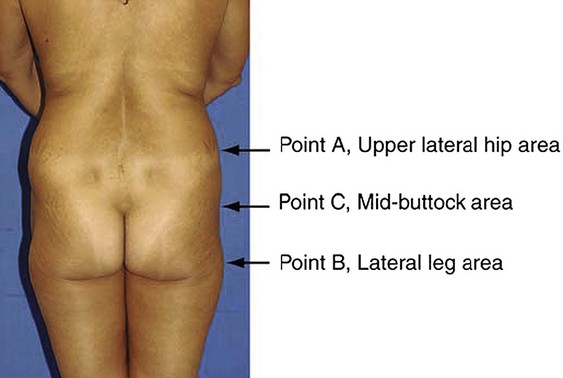

Mendieta begins with classification of the “frame”, which he defines as the bone, skin, and fat of the buttock region. Frame types are defined based on the location of three topographical landmarks: the “A” point representing the most protruding point in the upper lateral hip, the “B” point representing the most protruding point in the lateral thigh, and the “C” point representing the depression at the lateral mid-buttock (Fig. 39.3). The square buttock, most commonly seen, is defined as equal protrusion of points A and B. The round shape is similar, but is characterized as having excess fat deposition at point C. A-shaped frames are characterized as having more fat in the lateral upper thigh (B point); this is contrasted with the V-shaped frame which is characterized as having more fat in the upper lateral hip region (A point). These A-shaped and V-shaped frames have colloquially been referred to as “pear shaped” and “apple shaped”, respectively. Targeted liposculpture tends to be very effective in reshaping these frames to achieve a more esthetically pleasing gluteal region.

FIG. 39.3 Mendieta’s frame evaluation utilizing three critical landmarks.

(Mendieta C. Classification system for gluteal evaluation. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:333–346.)

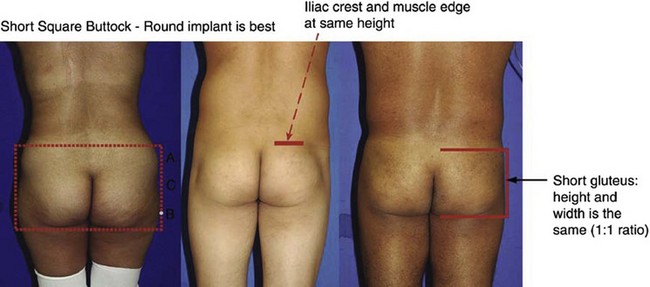

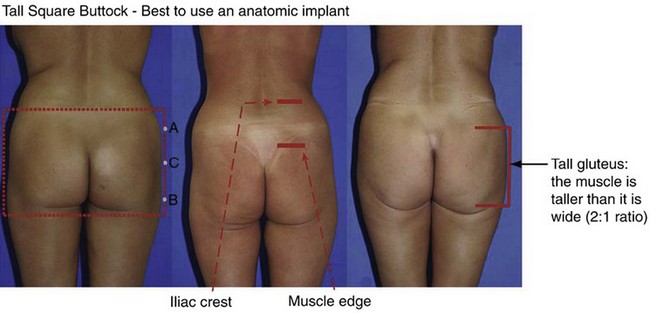

The gluteus maximus muscle can then be evaluated. Mendieta classifies the gluteal musculature based on its height-to-width ratio with 1 : 1 being defined as a short muscle, 2 : 1 being defined as a tall muscle, and those in between defined as an intermediate muscle (Fig. 39.4). This classification scheme is particularly critical when one is evaluating a patient for gluteal implant placement. Patients with short gluteus maximus muscles are best augmented with round implants, whereas those with tall muscles require an anatomic implant. For those with intermediate gluteal muscles, evaluation of projection and shape from a lateral view assists in determining the appropriateness of a round, anatomic or oval implant shape.

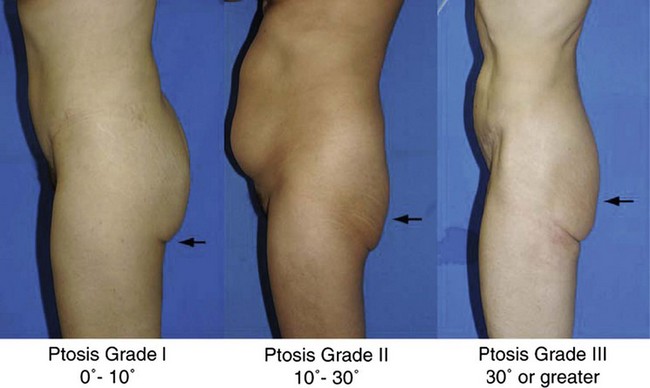

A gluteal ptosis classification scheme has also been devised by Mendieta, which is similar in design to that of breast ptosis described by Regnault.6 Those patients with some buttock volume and skin falling slightly below the infragluteal fold are described as having Grade I ptosis. Patients with an apparent and angular infragluteal fold with skin drooping below it are classified as having Grade II ptosis. Those patients with severe skin laxity, along with a laterally extending infragluteal fold with an angle of greater than 30° are classified as having Grade III ptosis (Fig. 39.5).

Surgical Technique

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – An Overview

Gluteal augmentation for reconstruction was first described by Bartels in 1969.7 Cosmetic correction of lateral gluteal depressions was subsequently undertaken by Cocke and Ricketson in 1973 with their utilization of mammary implants.8 Specific gluteal implants are now available in various shapes and textures. Numerous options for prosthetic implantation exist in Mexico and South America. Cohesive gel implants with a polyurethane textured surface allow implants to have a natural feel with less capsular contracture and a tendency to maintain their position. Unfortunately, the soft solid elastomer prostheses available in the United States are more rigid, leading to increased palpability and firmness.

Subcutaneous implant placement was originally described by Gonzalez-Ulloa.9 This approach has been abandoned secondary to unacceptably high complication rates and utilization of more appropriate tissue planes.

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Submuscular Approach

In 1984, Robles and colleagues described gluteal augmentation utilizing the submuscular space.10 This approach successfully addressed the capsular contracture and palpability complications seen with the subcutaneous approach. However, the anatomy of the submuscular space limits the augmentation that may be achieved. Because the sciatic nerve exits on the underside of the piriformis muscle at its inferior border, augmentation is limited to utilization of smaller round implants placed in a more superior location. This results in greater projection in the upper gluteal region with a deficiency in the lower portion (Fig. 39.6). Furthermore, with such superior placement, gluteal ptosis may not be appropriately addressed. Risk of direct injury to the sciatic nerve also accompanies this approach. While this technique may be used today for patients with a well-developed inferior gluteal region requiring upper pole augmentation, it has largely fallen out of favor with the advent of intramuscular and subfascial descriptions.

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Intramuscular Approach

The intramuscular approach to prosthetic gluteal augmentation provides padding both above and below the gluteal implant. Utilization of this space allows for better inferior placement when compared to the submuscular approach and decreases the risk of injury to the sciatic nerve (Fig. 39.7).

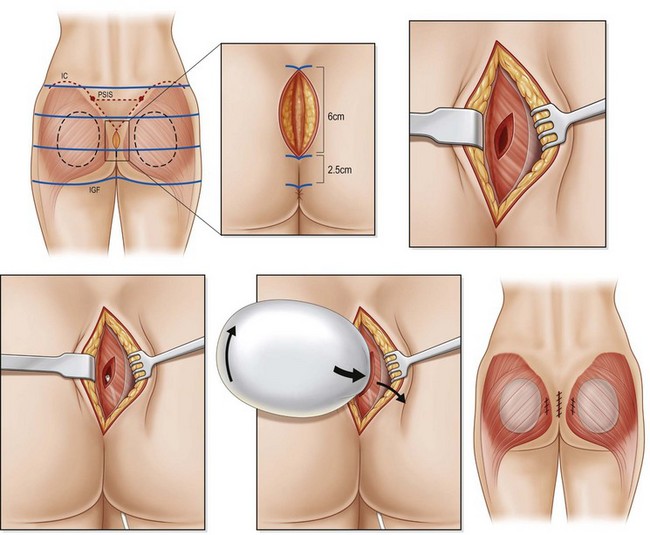

The authors prefer the technique outlined by Mendieta.11 Preoperative Decadron and clindamycin are administered and intermittent pneumatic compression stockings are applied. General anesthesia or epidural placement with IV sedation may be utilized. The patient is placed in the prone jackknife position with the entire gluteal region prepped and draped. A Betadine-soaked gauze is placed over the anus to prevent contamination of the surgical field. While a single midline approach had previously been advocated, two parasacral incisions are now utilized to minimize postoperative wound dehiscence. The midline is marked and two paramedian lines are drawn 1 cm lateral to the midline which curves to follow the upper gluteal curvature superiorly for a total length of 8 cm.

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Subfascial Approach

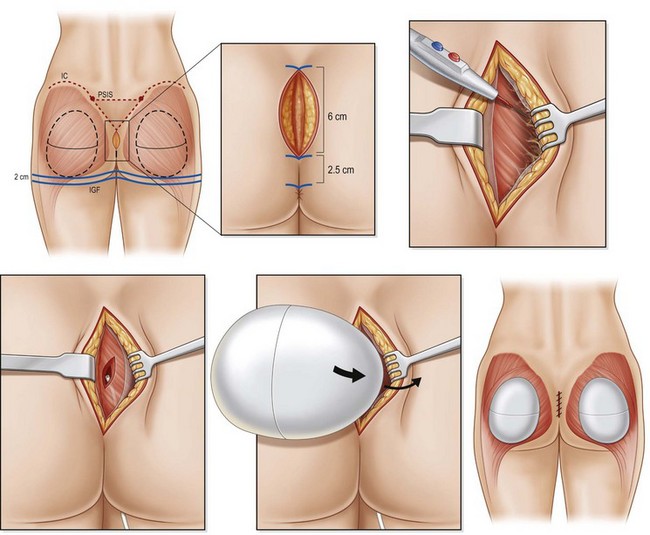

While rewarding and successful, the intramuscular approach may be frustrating to some surgeons, owing to its lack of a natural tissue plane. De la Pena describes his approach to subfascial gluteal augmentation, which exploits the natural subaponeurotic space to allow for implant placement.12 This space utilizes the gluteus maximus as a base for the implant to rest and is limited inferiorly by its fusion with the infragluteal fold, thus limiting implant migration.

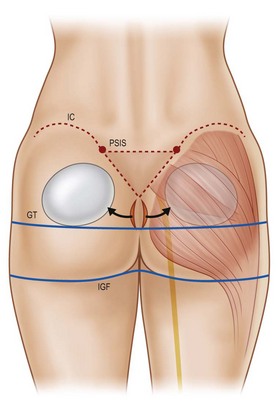

The authors prefer the description of this technique detailed by De la Pena.13 With the patient in a standing position, markings are made based on templates designed to estimate the volume implant to be placed. This template is centered over the gluteal region with a minimum of 2 cm separating the inferior margin from the infragluteal fold and 2 cm separating the medial margin from the lateral border of the sacrum (Fig. 39.8). Preoperative antibiotics are administered and sequential compression devices applied to the calves. General anesthesia or epidural placement with IV sedation may be administered. The patient is placed in the prone position with the gluteal region prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. A Betadine-soaked gauze is placed in the anus and covers the perineal area.

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Optimizing Outcomes

When performing prosthetic gluteal augmentation, utilization of the intramuscular or subfascial plane produces the most reliable long-term results with lower rates of morbidity (Table 39.1). The submuscular approach may be appropriate for those patients only requiring augmentation of the upper gluteal region. Paramedian skin incisions are preferred over midline incisions, which are associated with higher complication rates. Maintenance of a cuff of fascia (or gluteus muscle if using the submuscular or intramuscular approach) is necessary to allow for a deep closure with little tension. Utilization of long instruments and lighted retractors assists greatly in visualization and dissection of the implant pocket. Careful handling of the prosthesis must be ensured to minimize infectious complications. Finally, meticulous, tension-free, multilayered closure is paramount in reducing the risk of wound dehiscence and possible implant exposure (see Video Attachment 1).

TABLE 39.1 Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Planes of Dissection

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Submuscular | |

| Abundant soft tissue coverage | Augmentation limited to smaller round implants |

| Less palpable/visible | Greater superior projection |

| Decreased rates of capsular contracture | Deficient inferior projection |

| Increased risk of sciatic nerve trauma | |

| Fails to address gluteal ptosis | |

| Intramuscular | |

| Soft tissue padding above and below the implant | Technically difficult, indiscrete plane of dissection |

| Improved inferior placement | More painful postoperative recovery |

| Soft transition between edge of implant and surrounding soft tissue | |

| Subfascial | |

| Anatomic plane of dissection | Less soft tissue coverage, may result in implant exposure with wound dehiscence |

| Limited implant migration | Increased risk of palpable/visible implant |

Liposculpture – An Overview

Autologous fat transfer was initially described by Neuber in 1893; more recently this technique has been refined by the work of Coleman.13 Success has been attributed to deposition of small aliquots of centrifuged fat in a layered fashion into a well-vascularized bed. When applied to gluteal augmentation, this may be a powerful and long-lasting technique.14 When combined with liposuction of targeted regions of localized lipodystrophy, one may rejuvenate the buttock.

Cuenca-Guerra and Lugo-Beltran have analyzed the distribution of gluteal fat in elucidating how to better achieve the gluteal esthetic.2 They state the following: (1) The ratio of the anterior superior iliac spine to the greater trochanter and the greater trochanter to the lateral point of maximum projection of the buttock should not exceed 1 : 2 on lateral view; (2) A visible lumbosacral depression should aid in distinguishing the back from the buttocks; (3) Excess fat should be removed from the lumbosacral, subgluteal, flank, “love handle”, “saddle-bag,” and “banana roll” regions; (4) The point of maximum gluteal projection should correspond to the level of the mons pubis. It should be noted that one must not aggressively remove fat from the region just inferior to the infragluteal fold (“banana roll”), as this may exacerbate buttock ptosis.

When one understands the classification systems devised to characterize the various buttock morphologies, a systematic operative plan may be devised. More broadly, the regions which benefit most from liposuction are the flanks, presacral region, hips, inner thighs, outer thighs and “banana roll” areas.15 Lipoinjection may then be utilized to fill depressions, fill the trochanteric region and augment projection at the level of the mons pubis.

Liposculpture – Liposuction with Lipoinjection

Countless descriptions for the handling of harvest fat may be found in the literature. For the sake of this text, the authors will outline the technique described by Cardenas-Camarena in his 2011 publication examining 14 years of gluteal fat grafting.16 With the patient standing, markings are made over areas to be liposuctioned and lipoinjected. Preoperative antibiotics are administered. The patient is placed in the prone position and epidural block or general anesthesia is delivered. Liposuction is undertaken first, utilizing a tumescent technique (1 mg epinephrine in 1000 ml normal saline without the use of an anesthetic). Access incisions are made in the intergluteal fold, the superior portion of the posterior iliac crest and the subgluteal fold. The infiltration to aspiration ratio is approximately 1.5 : 1 and performed with 3–4 mm cannulae. Targeted liposuction is performed; when employed in the lumbosacral region, two 2 mm diameter silicone drains are placed and removed on postoperative day 4.

Autologous Tissue Flaps – An Overview

Patients presenting with excess truncal, gluteal and lateral thigh skin are often candidates for excisional procedures which utilize autologous tissue flaps to augment the gluteal region. Often, these are patients with significant weight loss following bariatric surgery or lifestyle changes. It is Lockwood’s popularization of the lower body lift, along with his description of the superficial fascial system (SFS) which form the cornerstone of today’s autologous gluteal augmentation procedures.17 His original description involved a correction of the lateral thighs and buttocks with anterior incision lines merging into the groin crease (Type I). Lockwood’s modification to include an abdominoplasty with this lift, creating a continuous circumferential incision has been termed a Type II lift. With the correction of posterior tissue excess, one may augment the gluteal region utilizing local tissue rotation flaps.

Autologous Tissue Flaps – Lower Body Lift with Autologous Gluteal Augmentation

Here, the authors prefer the technique described by Rubin.18 It should be noted that the surgical details below refer strictly to the gluteal augmentation portion of the larger lower body lift (Lockwood Type II) procedure.

Prior to embarking on markings for the procedure, the surgeon must understand that specific anatomic landmarks are of little value. Rather, one will note that a more superior resection will emphasize the waistline by directly excising overhanging flank rolls. This approach will elongate the buttocks, limit flap placement so maximum projection is more superior than ideal, violate the sacral triangle, and create a scar which may be visible in some clothing.18 At the same time, a more inferior incision (preferred by the author) allows for improved correction of the lateral thigh and buttocks. However, this incision placement will diminish waist definition.

It should be noted that in patients who have experienced massive weight loss after a prolonged history of obesity, satisfactory waist definition is very difficult to achieve secondary to the “barrel chest” deformity resultant from years of rib cage expansion.18

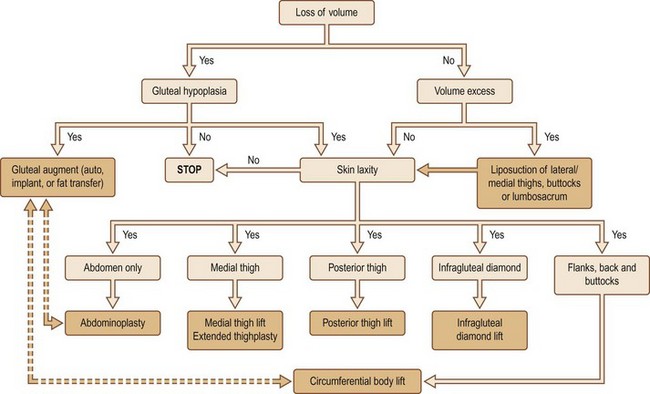

As previously discussed, the eight gluteal esthetic units and their subsequent derangement following massive weight loss must be understood and addressed. While patients who benefit from autologous tissue flaps for gluteal augmentation generally suffer volume loss, localized regions of relative volume excess, gluteal hypoplasia and skin integrity must be evaluated. Centeno has devised a massive weight loss gluteal contouring algorithm which assists greatly with this portion of the surgical planning stage (Fig. 39.9).18

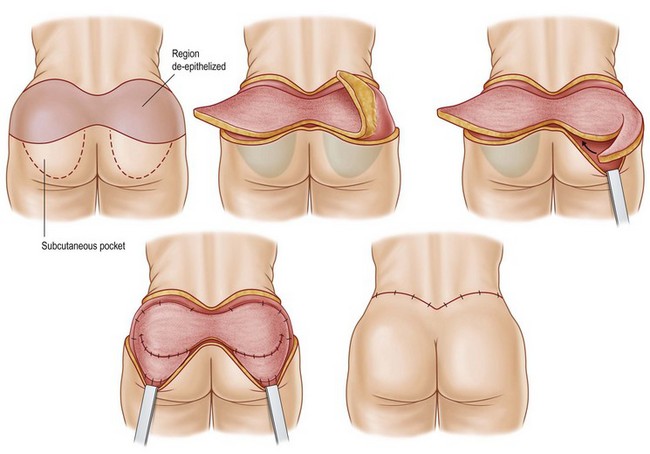

Preoperative antibiotics are administered within 1 hour of incision and can be redosed if the procedure exceeds 2 hours or if there is excessive blood loss. The patient is kept under forced air warming blankets in the preanesthesia area; these are also utilized intraoperatively in order to prevent hypothermia during the case. After general anesthesia is induced, a Foley catheter is placed and the patient is positioned in the prone position on the operating room table. Two arm boards are placed at the lower portion of the table so the legs may be abducted during the procedure. The buttocks and legs are prepped and draped in a circumferential fashion. Sterile drapes are wrapped around the legs from knees down to allow for intraoperative manipulation. A 1 : 100 000 epinephrine solution without anesthetic is infiltrated into the dermis to aid in hemostasis. The region of gluteal tissue marked for autoaugmentation is de-epithelialized, then circumscribed down to the fascial level. The lateral margin of resection is incised with excision of the marked tissues around the dermal pedicle at the level of the fascia. The circumscribed paddle is then undermined laterally at the level of the muscle fascia to allow for subsequent downrotation. A subcutaneous pocket is then undermined at the level of the muscle fascia, inferior to the lower incision line marking. The dermal-fat flaps are then rotated into this pocket and secured with permanent braided nylon suture. The surgeon may then elect to plicate the dermal surface of these flaps to enhance gluteal projection (Fig. 39.10).

Postoperative Care

Liposculpture

When liposuction is performed in the sacral region, a silicone drain is left in place and removed 4–5 days postoperatively. Patients are placed in a panty girdle compression garment which is worn for 6 weeks. Therapeutic ultrasound massage is initiated at that time and continued every third day for a total 1 month course.19 If deemed necessary, 15–20 Endermologie sessions may follow this course of ultrasonic massage. Normal activities may be resumed at 2 weeks after surgery and gradual initiation of exercise may begin at 4 weeks postoperatively.

Complications

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation

The evolution of prosthetic-based gluteal reconstruction discussed above has allowed for a decrease in postoperative complications. As mentioned, the subcutaneous plane has been fraught with complications and has since been abandoned. Wound dehiscence had previously been reported to occur in approximately 30% of cases. This rate has declined with the increased popularity of using paramedian instead of midline incisions. This is felt to be secondary to a number of factors: (1) The intergluteal crease has an intrinsically poor blood supply and is considered a “watershed” area; (2) Prolonged retraction may crush and traumatize the local tissues; and (3) Inadequate or high tension muscle or fascial closure.20 Should a wound dehiscence occur without implant exposure, these wounds will typically heal secondarily without long-term sequelae. Implant exposure is an indication for explant. The rate of exposure is quoted at 2–5% but is significantly higher in patients who are overweight or receiving implants larger than 350 cm3. Utilization of large implants (greater than 545 cm3) has also been associated with severe inferior ptosis.

Implant asymmetry or migration are more common when the intramuscular approach is employed, as this involves creation of an unnatural tissue plane. It is common to inadvertently allow dissection to become too superficial when one works superolaterally. Because the gluteus maximus muscle forms the base on which an implant sits in the subfascial location, with the robust muscle fascia overlying it, implant malposition is less common utilizing a subfascial technique. Furthermore, the close proximity of the sciatic nerve during intramuscular dissection may limit the amount of inferior dissection required for optimal implant placement. However, permanent injury to the sciatic nerve using this approach is exceedingly rare. Mendieta has noted transient sciatic parasthesias in approximately 20% of patients undergoing intramuscular augmentation, which respond to gabapentin and resolve within 3 weeks.21

Liposculpture

Cardenas-Camarena and colleagues present an excellent review of the evolution of their gluteal fat grafting technique over a 14-year timeframe.16 The authors found that complications such as fat necrosis, gluteal erythema, infection, and fat embolism syndrome were more common when fat infiltration volumes were small and localized. The injection of large volumes of fat into single small areas in one layer place the patient at increased risk of local complications and fat necrosis. By increasing the area to be infiltrated and utilizing multiple layers of deposition, these complications may be minimized.

More rare, and feared, complications have been described. These include transient blindness, necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis.22,23

Autologous Tissue Flaps

Shermak and colleagues have described the management of seromas in the massive weight loss population in outstanding detail.24 The majority of seromas encountered resolve utilizing serial aspiration. Those recalcitrant to this line of therapy may resolve with placement of an indwelling catheter or sclerotherapy (500 mg of doxycycline in 50 ml of normal saline). Failure of sclerotherapy requires operative excision of the established seroma cavity.

Other complications, including infection, skin and fat necrosis, scarring and venous thromboembolism have been described but are far less common than wound dehiscence and seroma formation. For patients undergoing autologous gluteal augmentation, Colwell et al have demonstrated that patients with an operative BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater are at significantly increased risk of wound, seroma and fat necrosis complications.25 Patient selection remains paramount in minimizing the risk of postoperative complications.26

1 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Report of the Plastic Surgery Statistics. Online. Available from http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/news-resources/statistics/2010-statisticss/Top-Level/2010-US-cosmetic-reconstructive-plastic-surgery-minimally-invasive-statistics2.pdf, 2010. accessed 17 April 2012

2 Cuenca-Guerra R, Lugo-Beltran I. Beautiful buttocks: characteristics and surgical techniques. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:321–332.

3 Roberts T, Weinfeld A, Bruner T, et al. “Universal” and ethnic ideals of beautiful buttocks are best obtained by autologous micro fat grafting and liposuctions. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(3):371–394.

4 Centeno R. Gluteal aesthetic unit classification: a tool to improve outcomes in body contouring. Aesth Surg J. 2006;26:200–208.

5 Mendieta C. Classification system for gluteal evaluation. Clin Plastic Surg. 2006;33:333–346.

6 Regnault P. Breast ptosis. Definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3(2):193–203.

7 Bartels R, O’Malley J, Douglas W, et al. An unusual use of Cronin breast prosthesis. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;44:500.

8 Cocke W, Ricketson G. Gluteal augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;52:93.

9 Gonzalez-Ulloa M. Gluteoplasty: a ten year report. Aesth Plast Surg. 1991;5:85–91.

10 Robles J, Tagliapietra J, Grandi M. Gluteoplastia de aumento: implane submusular. Cir Plast Iberolatinoamericana. 1984;10:365–369.

11 Mendieta C. Intramuscular gluteal augmentation technique. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:423–434.

12 De la Pena J. Subfascial technique for gluteal augmentation. Aesth Surg J. 2004;24:265–273.

13 Coleman S. Structural fat grating: more than a permanent filler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:108S–120S.

14 Avendano-Valenzuela G, Guerrerosantos J. Contouring the gluteal region with tumescent liposculpture. Aesth Surg J. 2011;31(2):200–213.

15 Aiache A. Gluteal recontouring with combination treatments: implants, liposuction, and fat transfer. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:395–403.

16 Cardenas-Camarena L, Arenas-Quintana R, Robles-Cervantes J. Buttocks fat grafting: 14 years of evolution and experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:545–555.

17 Lockwood T. Superficial fascial system (SFS) of the trunk and extremities: a new concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1009–1018.

18 Centeno RF, Mendieta CG, Young VL. Gluteal contouring surgery in the massive weight loss patient. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35:73–91.

19 Cardenas-Camarena L, Silva-Gavarrete J, Arenas-Quintana R. Gluteal contour improvement: different surgical alternatives. Aesth Plast Surg. 2011;35(6):1117–1125.

20 Bruner T, Roberts T, Nguyen K. Complications of buttocks augmentation: diagnosis, management, and prevention. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:449–466.

21 Mendieta C. Intramuscular buttocks implant augmentation. Chicago: Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Plastic Surgery; 2005. Sept 27

22 Talbot S, Parrett B, Yaremchuck M. Sepsis after autologous fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(4):162e–164e.

23 Sherman J, Fanzio P, White H, et al. Blindness and necrotizing fasciitis after liposuction and fat transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(4):1358–1362.

24 Shermak MA, Rotellini-Coltvet L, Chang D. Seroma development following body contouring surgery for massive weight loss: Patient risk factors and treatment strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:280–288.

25 Colwell A, Borud L. Autologous gluteal augmentation after massive weight loss: aesthetic analysis and role of the superior gluteal artery perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:345.

26 Michaels V, Coon D, Rubin JP. Complications in postbariatric body contouring: postoperative management and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1693.