Glucose metabolism and diabetes mellitus

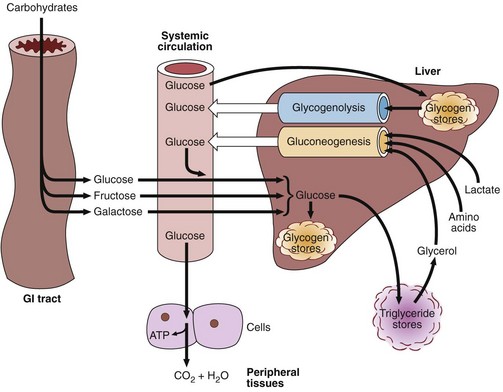

Dietary carbohydrate is digested in the gastrointestinal tract to simple monosaccharides, which are then absorbed. Starch provides glucose directly, while fructose (from dietary sucrose) and galactose (from dietary lactose) are absorbed and also converted into glucose in the liver. Glucose is the common carbohydrate currency of the body. Figure 31.1 shows the different metabolic processes that affect the blood glucose concentration. This level is, as always, the result of a balance between input and output, synthesis and catabolism.

Insulin

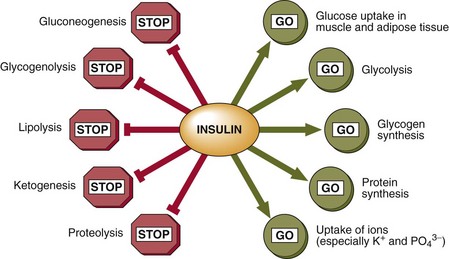

Insulin signals the fed state. It switches on pathways and processes involved in the cellular uptake and storage of metabolic fuels, and switches off pathways involved in fuel breakdown (Fig 31.2). It should be noted that glucose cannot enter the cells of most body tissues in the absence of insulin.

Diabetes mellitus

Primary diabetes mellitus is generally subclassified into Type 1 or Type 2. These clinical entities differ in epidemiology, clinical features and pathophysiology. The contrasting features of Types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus are shown in Table 31.1.

Table 31.1

Type 1 versus Type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Main features | Type 1 | Type 2 |

| Epidemiology | ||

| Frequency in northern Europe | 0.02–0.4% | 1–3% |

| Predominance | N. European | Worldwide |

| Caucasians | Lowest in rural areas of developing countries | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Age | <30 years | >40 years |

| Weight | Low/normal | Increased |

| Onset | Rapid | Slow |

| Ketosis | Common | Under stress |

| Endogenous insulin | Low/absent | Present but insufficient |

| HLA associations | Yes | No |

| Islet cell antibodies | Yes | No |

| Pathophysiology | ||

| Aetiology | Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic islet cells | Impaired insulin secretion and insulin resistance |

| Genetic associations | Polygenic | Strong |

| Environmental factors | Viruses and toxins implicated | Obesity, physical inactivity |

Late complications of diabetes mellitus

Microangiopathy is characterized by abnormalities in the walls of small blood vessels, the most prominent feature of which is thickening of the basement membrane. It is associated with poor glycaemic control.

Microangiopathy is characterized by abnormalities in the walls of small blood vessels, the most prominent feature of which is thickening of the basement membrane. It is associated with poor glycaemic control.

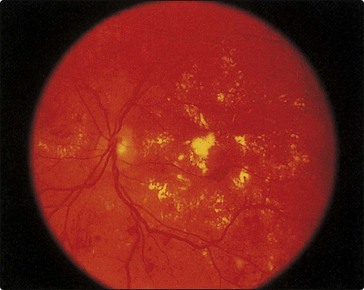

Retinopathy may lead to blindness because of vitreous haemorrhage from proliferating retinal vessels, and maculopathy as a result of exudates from vessels or oedema affecting the macula (Fig 31.3).

Retinopathy may lead to blindness because of vitreous haemorrhage from proliferating retinal vessels, and maculopathy as a result of exudates from vessels or oedema affecting the macula (Fig 31.3).

Nephropathy leads ultimately to renal failure. In the early stage there is kidney hyperfunction, associated with an increased GFR, increased glomerular size and microalbuminuria (see p. 35). In the late stage, there is increasing proteinuria and a marked decline in renal function, resulting in uraemia.

Nephropathy leads ultimately to renal failure. In the early stage there is kidney hyperfunction, associated with an increased GFR, increased glomerular size and microalbuminuria (see p. 35). In the late stage, there is increasing proteinuria and a marked decline in renal function, resulting in uraemia.

Neuropathy may become evident as diarrhoea, postural hypotension, impotence, neurogenic bladder and neuropathic foot ulcers due to microangiopathy of nerve blood vessels and abnormal glucose metabolism in nerve cells.

Neuropathy may become evident as diarrhoea, postural hypotension, impotence, neurogenic bladder and neuropathic foot ulcers due to microangiopathy of nerve blood vessels and abnormal glucose metabolism in nerve cells.

Macroangiopathy (or accelerated atherosclerosis) leads to premature coronary heart disease. The exact underlying mechanisms are unclear, although the (compensatory) hyperinsulinaemia associated with insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes may play a key role. Certainly, the dyslipidaemia seen in these patients (increased triglycerides, decreased HDL-cholesterol, and a shift towards smaller, denser LDL) is considered highly atherogenic.

Macroangiopathy (or accelerated atherosclerosis) leads to premature coronary heart disease. The exact underlying mechanisms are unclear, although the (compensatory) hyperinsulinaemia associated with insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes may play a key role. Certainly, the dyslipidaemia seen in these patients (increased triglycerides, decreased HDL-cholesterol, and a shift towards smaller, denser LDL) is considered highly atherogenic.