GINGER

Botanical name: Zingiber officinalis

PRINCIPAL USES

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

The aromatic principles of ginger are considered responsible for its medicinal actions, including enzymatic inhibition of prostaglandin, thromboxane, and leukotriene synthesis. The mechanisms of action on nausea and vomiting remain uncertain, with studies demonstrating increased gastric motility contradictory to those showing no motility. Another theory is that the herb acts via a centrally mediated effect on 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3), an effect that has been demonstrated in vitro. There is some evidence that ginger increases stomach acid production, thus possibly interfering with antacid medications.

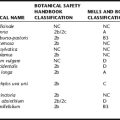

RATINGS

SAFETY INFORMATION: HERB DRUG INTERACTIONS, TOXICITY, AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Ginger has a long history of safe use both as a culinary and medicinal herb. It is considered safe when used as recommended, including when used within the prescribed pregnancy dose. Dose should not exceed 1 g daily in pregnancy, and 4 g per day for the general population. Theoretical herb drug interactions have been proposed (Table 1). Concerns have been expressed that ginger might increase the risk of bleeding, for example, with surgery, owing to platelet activating factor (PAF) inhibition; therefore, it is recommended that patients taking ginger should discontinue use 1 to 2 weeks prior to surgical procedures. Patients using oral hypoglycemic medications may require a dose adjustment as ginger may have hypoglycemic effects. Limited evidence suggests that ginger may interfere with antacids, sulcralfate, H2 antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) by increasing stomach acid production. Patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers are therefore sometimes advised to avoid using ginger other than for culinary purposes for this reason; however, animal experiments suggest a protective effect against gastric ulcers.

| DRUG | ACTUAL OR THEORETICAL | INTERACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Antacids, gastric acid inhibiting drugs | Theoretical | Ginger may increase stomach acid production, therefore interfering with the actions of antacids, sucralfate, H2 antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Ginger also may have a gastroprotective effect. |

| Anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs | Theoretical | Because ginger has been observed to inhibit both PAF and thromboxane synthetase, it has been proposed that ginger may increase bleeding time and increase the risk of bleeding with anticoagulant and thrombolytic medications. However, this is not supported by case reports, adverse events reports, or the clinical literature. |

| NSAIDs | Theoretical | Also caused by inhibition of thromboxane synthetase, theoretical interaction with NSAIDs has been proposed, also leading to increased bleeding risk and potentiation of effects. |

| CNS depressants | Theoretical | Large doses of ginger have been reported to lead to CNS depression; thus, there is a theoretical risk of interaction. |

| Cardiac drugs, including β-blockers, digoxin, and positive inotropes | Theoretical | Inotropic effects of ginger have been proposed; and thus a theoretical risk of interaction with cardiac drugs. However, this has not been observed clinically. |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | Theoretical | Ginger has demonstrated hypoglycemic effects; thus, a dose-adjustment of oral hypoglycemic medications may be required for those taking this herb. |