Giddiness

Giddiness or dizziness are terms used by patients to describe a wide variety of sensations. It is crucial to obtain a precise understanding of the patient’s presenting complaint in order for clinical evaluation to proceed along appropriate lines. Table 1 summarizes the symptoms commonly described as ‘giddiness’.

Table 1 Symptoms commonly described as giddiness

| Symptom | Clinical interpretation | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Feeling of relative movement (usually spinning) of self and environment | Vertigo | Peripheral or central vestibular disturbance |

| Feeling of lightheadedness and impending faintness | Presyncope | See page 44 |

| Feeling of altered awareness and impaired consciousness | Altered consciousness | Consider complex partial seizures, absence attacks |

| Unsteadiness with a clear head | Ataxia | Cerebellar or proprioceptive |

Vertigo

Clinical assessment

Key features in the clinical assessment are as follows:

Head movement: is vertigo triggered by certain head positions? This usually signifies a peripheral lesion, most commonly BPPV.

Head movement: is vertigo triggered by certain head positions? This usually signifies a peripheral lesion, most commonly BPPV. Auditory dysfunction: is there deafness or tinnitus? This points to a disturbance of the labyrinth or vestibulocochlear nerve. Once in the brain stem, auditory and vestibular function are separate.

Auditory dysfunction: is there deafness or tinnitus? This points to a disturbance of the labyrinth or vestibulocochlear nerve. Once in the brain stem, auditory and vestibular function are separate.Types

Intermittent vertigo

Positional

BPPV is the most common cause and is easily recognized. It may follow viral infection or head trauma. There is often a period of a few days when patients are bed bound, because rising triggers disabling attacks of vertigo and vomiting. They then suffer brief attacks of vertigo, for up to 60 s, each time they put their head into a particular position, usually on lying down. This settles over a period of weeks but may recur. Hallpike’s test shows characteristic responses (see below). Other causes of positional vertigo include alcohol and anticonvulsant intoxication, perilymph fistula (often post-traumatic and usually with a hearing deficit) and, rarely, central oculomotor disorders with failure of vestibulo-ocular reflexes (see below and p. 18).

Sustained vertigo

The commonest peripheral cause is idiopathic vestibular neuritis, which is believed to be due to infection. There is an acute onset of vertigo, which persists for several weeks and gradually subsides. There is gaze-evoked nystagmus, with a rotatory component. There is canal paresis on caloric testing (see below). Many other acute vestibular lesions also produce this picture, including trauma, infarction (hyperviscosity syndromes), tumours (especially acoustic nerve tumours and Schwannomas) (p. 96) and infections. Important identifiable infections causing this syndrome include syphilis, tuberculosis and Lyme disease. Herpes zoster virus causes acute vertigo, unilateral hearing loss, ipsilateral facial paresis, severe pain, malaise and characteristic herpetic vesicles around the external auditory meatus: ‘Ramsay Hunt syndrome’. It responds to aciclovir.

Phobic vertigo

Phobic vertigo is usually characterized by a more vague sensation of unsteadiness that often fluctuates rather than being continuous or coming in discrete attacks. There may be associated symptoms of hyperventilation – difficulty catching the breath and paraesthesiae – and symptoms may be reproduced by hyperventilation. It is sometimes due to failure of compensation following previous vestibular disturbance or may be a primary psychogenic disturbance.

Specialized clinical tests

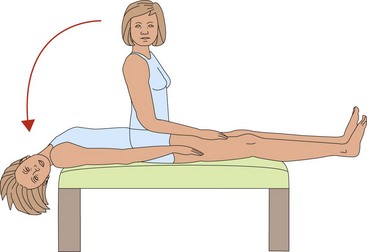

Hallpike’s manoeuvre may elicit the typical abnormality of BPPV. The patient is lowered down rapidly into the position which elicits vertigo (Fig. 1). There is:

Vestibulo-ocular response (VOR) tests ‘doll’s eye movements’ pathways between the vestibular system and the nuclei controlling eye movements. VOR can be tested at the bed side by sitting opposite the patient and asking them to look at one of your eyes and then gently rotating their head from left to right and up and down. The patient’s eyes should remain fixed on yours. Failure to maintain fixation, which may occur in only one direction, implies a lesion of the VOR, which can be central or peripheral. If eye movements are normal, you can also test the fast VOR using the head thrust test (Appendix 2). If this is abnormal, this indicates a peripheral vestibular lesion, for example idiopathic vestibular neuritis.

Investigations

Caloric tests. Water is introduced into one external auditory canal at 32°C and 41°C. This normally causes nystagmus with specific latency and duration that can be measured. Cold causes the fast phase of the nystagmus to the Opposite side and Warm to the Same side (COWS).

Caloric tests. Water is introduced into one external auditory canal at 32°C and 41°C. This normally causes nystagmus with specific latency and duration that can be measured. Cold causes the fast phase of the nystagmus to the Opposite side and Warm to the Same side (COWS). Auditory evoked potentials measure delay in central auditory pathways, especially in multiple sclerosis (p. 33).

Auditory evoked potentials measure delay in central auditory pathways, especially in multiple sclerosis (p. 33).Treatment

Treatment can be symptomatic or specific, and is directed at the underlying cause.

Symptomatic

Antihistamines, e.g. betahistine and cinnarizine. These are sedative, and patients should not operate machinery or drink alcohol.

Antihistamines, e.g. betahistine and cinnarizine. These are sedative, and patients should not operate machinery or drink alcohol. Dopaminergic antagonists, e.g. prochlorperazine and metaclopramide. These are mildly sedative but extrapyramidal side effects occasionally occur acutely and are common in long-term use (>6 months).

Dopaminergic antagonists, e.g. prochlorperazine and metaclopramide. These are mildly sedative but extrapyramidal side effects occasionally occur acutely and are common in long-term use (>6 months).Specific

Benign positional vertigo

Positioning manoeuvres have been demonstrated to be effective. This syndrome is caused by debris within the semicircular canals. Positioning so as to remove this is curative, and can be done using several different manoeuvres, such as the Epley manoeuvre (Appendix 3), or using Brandt–Daroff exercises.