Chapter contents

5.1 Positioning the patient 46

5.2 Locating the radial artery 47

5.3 Locating the pulse positions for assessment 49

5.4 Practitioner positioning 51

5.5 Assessing the parameters 51

5.6 Locating the pulse depth 53

5.7 The normal pulse 56

5.8 Assessing health by the pulse 57

5.9 Channel, organ and levels of depth 58

5.10 Comparison of the overall force of the left and right radial pulse 58

5.11 Pulse method 59

5.12 Other considerations when assessing the pulse and interpreting the findings 61

5.13 Summary 68

Although an objective terminology is essential for radial pulse diagnosis, it is equally imperative to have reliable procedures and a consistent method when palpating the pulse. Pulse procedures refers to the processes preceding pulse assessment as well as the actual techniques used during this process. These procedures encompass:

• Positioning of the patient and practitioner

• Procedure for locating the three pulse positions

• Techniques for locating and assessing the different levels of depth

• Assessment of the arterial structure and pulse wave contour.

The ordering of these techniques and procedures is described as the pulse method. As we established in Chapter 4, pulse method refers to:

• How and when to apply the pulse taking

• The order of gathering information from the pulse using the different techniques (depth, length, strength of application) and required body part (pulse position)

• The consistent application of the pulse method and techniques used in the same way every time.

Identification of many of the specific CM pulse qualities depends on the measurement of pulse parameters in specific positions, so a consistent method is of vital importance. The objective for developing and using a consistent method of pulse palpation is to limit the variance of pulse findings attributable to technique. Once such variances are controlled, then any findings with palpation can be confidently attributed to the occurrence of actual pulse differences.

This chapter focuses extensively on the first stage of the pulse diagnosis process — the application of correct technique and procedures. A further stage of the pulse diagnosis process, interpreting pulse assessment findings diagnostically, is dealt with extensively in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7. We also investigate the organization of the techniques and procedures and their order of application, and discuss the benefits of developing a pulse method that is systematic in its application.

5.1. Positioning the patient

Before the pulse is assessed, the patient needs to be positioned appropriately. Appropriate patient positioning allows the practitioner maximal access to the radial artery for assessment purposes while preventing any postural changes that may affect blood flow. For example, if the patient slouches, their respiration will be poor and this will cause a corresponding decrease in pulse strength. Postural slouching and arterial compression from poor arrangement of the upper limbs impede blood flow from the central arteries into the peripheral arteries, limiting the propulsion effect that the pressure wave has on moving blood. In this situation any assessment of the pulse will be inaccurate and unreliable.

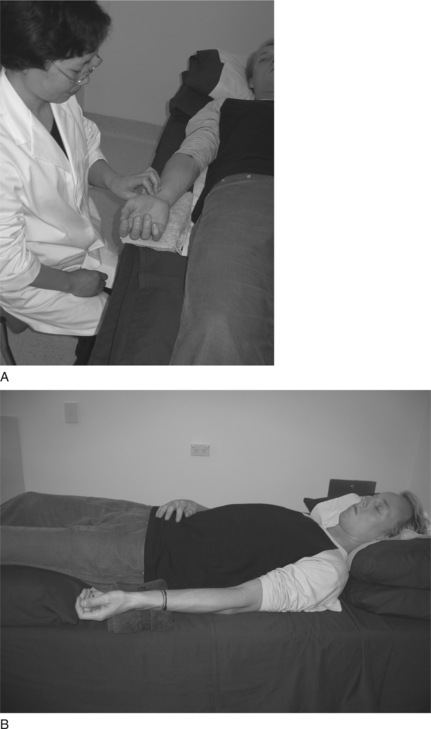

The pulse is most commonly taken when the patient is seated, but assessment can also occur when the patient is lying supine (Box 5.1). Irrespective of the positioning approach used, the arm is always placed at the level of the patient’s heart. Holding the arm lower or higher than the heart level affects the pulse pressure, causing changes in the pulse wave. Ensuring that the arm is level will minimise these postural related pressure differences. Pulse examination is undertaken on both the left and right arms (Fig. 5.4).

Box 5.1

Positioning the patient for assessing the pulse

• Arm level with the heart

• Patient’s legs uncrossed

• Patient should be sitting upright or lying supine

• Support the wrist when extended with a towel or cushion

|

| Figure 5.4Bilateral hand palpation. The practitioner’s left hand is palpating the right pulse and the right hand is palpating the left hand the pulse. |

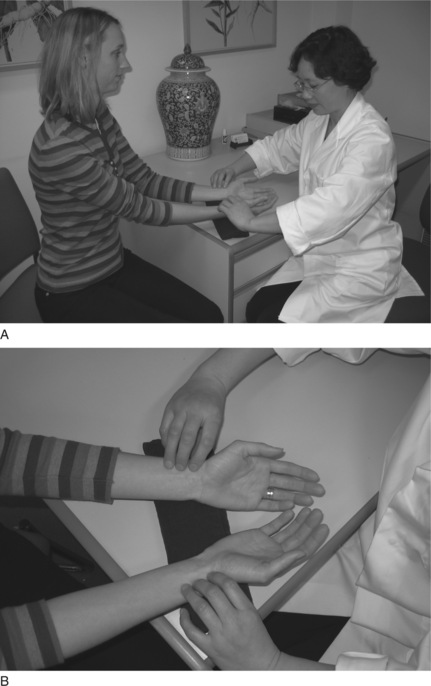

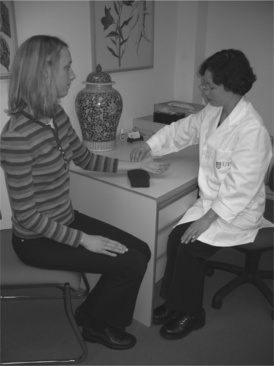

If sitting, the patient’s legs should be uncrossed with feet placed flat on the floor. Their posture should be relaxed but upright so that the thorax region is not constricted during respiration, allowing the lungs to expand and contract freely. The wrist should be extended straight with the palm facing upwards (Fig. 5.1). Similarly, when lying supine, the patient should have their legs uncrossed, wrist extended with the palm facing upwards (Fig. 5.2).

|

| Figure 5.1Positioning of the practitioner taking the pulse when the patient is sitting. The patient’s legs uncrossed, feet flat on floor, with palms upwards. The patient should be in a comfortable upright position and their wrists supported. |

|

| Figure 5.2Positioning of the practitioner taking the pulse when the patient is supine. Note that the patient’s arm is by their side and the wrist is supported for maximal access to the artery. |

A folded towel or small cushion can be used to support the wrist if necessary in either the supine or sitting positions. This ensures that the radial artery is easily accessible and that the blood flow is unimpeded. Additionally, such support limits any movement in the wrist that maybe introduced by the practitioner when applying finger pressure to assess the pulse at different levels of depth.

5.1.1. Speaking

Ideally there should be no speaking between the practitioner and patient during the pulse assessment process. When the patient speaks this will change their respiration, position of the diaphragm and oxygen requirements, also changing the pulse contour and pulse rate.

When the practitioner speaks during the pulse assessment, this often is a sign that they are not focused on the assessment process. Occasionally, speaking is required and is usually done in response to further elucidation of any pulse findings. For example, the presence of missed beats requires further questioning to determine whether the patient was aware of this. This should be kept to relevant questions if concurrently assessing the pulse.

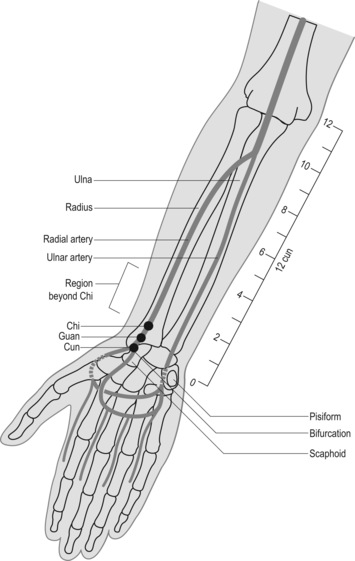

Once the patient and wrist region are appropriately positioned, the next step is to locate the artery, andin particular, the radial pulse sites used for pulse examination. As described in Chapter 2, the radial artery is located on the lateral portion of the anterior forearm. It extends from the elbow, where the brachial artery bifurcates, to the wrist crease, at which point the radial divides further into other arterial segments. (When seen from the perspective of channel physiology, the radial artery follows the course of the Lung channel.) The CM pulse sites used for pulse assessment are located in the wrist portion of the artery only. At this region, the radial artery is usually quite easily palpated because of its close proximity to the skin surface and its position over a hard surface — in this case the radial bone. The radial bone provides a firm support to the radial artery when external pressure is applied. If there were no support then it would be difficult to clearly distinguish the pulse parameters or apply different levels of pressure without the artery moving.

The portion of the radial pulse used for assessment is located proximal to the wrist crease directly above the pulsation of the radial artery adjacent to the styloid process of the radius. This is known as the Cun Kou pulse, and from the time of the Nan Jing it was considered to be the convergence point of movement through all the conduit vessels. The Second Difficult Issue in the Nan Jing discusses the length of the Cun Kou position, describing it as 1.9 Cun in length. Proportionally, this is about one sixth of the area between the transverse elbow crease and the wrist crease, assuming the length of the forearm is 12 Cun (or anatomical units) (see Fig. 5.3). In metric measurement this is approximately 3–5 cm. However, exact measurements are not necessarily applied because locating the pulse positions primarily depends on the location of the styloid process and the relative size of the patient.

|

| Figure 5.3Styloid process, the radial artery and location of the three pulse positions Cun, Guan and Chi and other related anatomical structures. The Cun (inch) measurements indicate the portion of the artery used for pulse assessment. |

5.2.1. Deviated artery: abnormalities of the radial artery

In a small percentage of people the radial artery is anatomically deviated from the anterior to the lateral portion of the arm as it nears the wrist. In these individuals the artery winds laterally around the styloid process and travels on the posterior side of the wrist (in the anatomical position) as if following the path of the Large Intestine channel through the anatomical snuffbox rather than the path of the Lung channel. This is termed a Fan Guan Mai or simply a ‘pulse on the back of the wrist’ pulse by Wiseman & Ye (1998: p. 473, p. 470).

5.2.2. When to look for a deviated radial artery

If the pulse appears to be absent or extremely faint, look for the presence of a pulsation on the posterior or lateral part of the wrist, in the vicinity of the radial styloid process. If there is a significant pulsation, this indicates a deviated radial artery. In this case, the radial artery runs very superficially and both the artery and pulsations can be easily observed. When the artery is located at this region, the pulse cannot be used for palpation purposes except for assessing rate and rhythm.

A deviated arterial artery is not considered pathological from either a CM or a biomedical perspective. Such deviations represent normal individual variation. However, if the pulsation is not felt in the Cun Kou area or an alternative position, then this may be perceived as pathological. The Cun Kou area should be re-examined, with particular attention to the deep level of depth.

5.2.3. Other abnormalities

Other ‘abnormalities’ that can similarly affect the presentation of the arterial pulsation include:

• Ganglions

• Bone spurs and growths

• Surgical procedures for carpal tunnel syndrome rearranging soft tissue structures

• Other surgical procedures for arthritis in which carpal bones can be removed

• Scarring, especially keloid tissue

• Inflammatory conditions of the tendons.

5.3. Locating the pulse positions for assessment

Once the Cun Kou region of the artery proximal to the wrist is located, the pulse positions used for pulse assessment must be identified. There are three of these positions, and they are found by dividing the Cun Kou region into three portions using the styloid process of the radius as a guide. The three positions are:

• Cun (inch): Located proximal (or closest) to the wrist crease

• Guan (bar): Located medial to the styloid process of the radius

• Chi (cubit): Most distal (furthermost) position from wrist crease.

Because the three pulse positions are determined proportionally according to an individual’s size, this means that the same procedure needs to be followed every time to ensure exact location of these positions within the same physique and between different physiques (Box 5.2). Of the three positions Cun, Guan and Chi, it is the central position Guan which is associated with a specific surface anatomical landmark; the styloid process. For this reason, the Guan position should always be located first as the locations of the Cun and Chi positions depend on the initial location of Guan.

Box 5.2

Locating the three positions

• Index finger is placed at the Cun position

• Middle finger is placed at the Guan position

• Ringer finger is placed at the Chi position

• Thumb is placed on the underside of the wrist

5.3.1. Locating Guan

The Guan position is found first as it is easily located adjacent to the styloid process of the radius. The styloid process is a flaring of the radial bone, and can be identified as a bony protuberance on the lateral side of the wrist, proximal to the wrist crease (in the anatomical position). To locate the styloid process it is best to palpate the bone as it is not always easy to identify this landmark by observation alone. By gently running the index finger over the region a distinct ‘bump’ can be felt where the styloid process flares away from the shaft of the radius. The styloid process can also be clearer to palpate with radial/ulnar deviation, causing the soft tissue to stretch and expose the bone. Once it is located, the practitioner moves directly medial towards the soft skin of the anterior wrist above the radial artery. The arterial pulsations are often felt most distinctly in this position, and the outer border of the styloid process may be felt at the margin of the finger when positioned on the artery. This is the Guan position. When the middle finger is placed on the Guan position, the other two fingers should fall naturally into their positions: the index finger on Cun, located adjacent to the scaphoid bone, and the ring finger on Chi, proximal to Guan.

The actual finger placement is proportional to the size of the wrist: on a tall person the wrist is larger, and so the three positions and fingers are spaced further apart. Conversely, on a shorter person the wrist is proportionally smaller and so the three fingers are positioned closer together. However, for all patients the positioning of the fingers on the pulse should always be undertaken in reference to the styloid process and the location of the Guan position. Using either the Cun or the Chi position for this purpose will lead to incorrect placement of the fingers. (This doesn’t work with children.)

With the practitioner’s thumb resting lightly on the back of the patient’s wrist the fingers should be arranged so that the tips are level with one another. It is the tips of the fingers which should be used for palpation, exerting equal pressure to feel the three pulse positions simultaneously. The fingers can be used:

• Simultaneously to palpate all three pulse positions on one arm

• For comparative purposes, assessing the overall pulse in one side with the other

• Individually to assess pulse positions at different levels of depth.

5.3.2. Placement of the thumb

In the process of placing the fingers on the appropriate pulse positions and undertaking assessment, the thumb is of particular importance. The thumb is used to stabilise the wrist against movement that may occur when different pressures are applied by the fingers to the pulse. If the patient’s wrist moves during palpation this will render the reliability of the findings questionable. For example, if a particular amount of strength is used to move the fingers into the deep level of depth, but the wrist is unsupported, then the wrist may move so that rather than palpating the deep level the practitioner may assess only the middle level of depth without realising this is the case. For this reason, the thumb is placed on the posterior wrist region to provide support to the wrist and leverage for the fingers when palpating the pulse.

5.3.3. The anatomy of the radius and support of the radial artery

Because of the shape of the radial bone and the depression formed between it and the styloid process, the support provided by the styloid to the radial artery at the wrist varies. For example, at the Guan position the pulse wave and arterial structure are both felt more distinctly than at the Cun or Chi position alone. Because of the support offered by the styloid bone at the Guan position, the artery sits relatively superficial. Less skin, and thinner epidermal/fasciae layers, mean a ‘clearer’ pulse image when palpating and facilitates better detection of arterial parameters such as tension.

At the Chi position the radial bone sinks away from the surface with the artery similarly becoming deeper. In order to detect pulses clearly it is often necessary to provide support under the artery. Having the artery supported means it can be compressed and so the pulse is detectable for diagnostic purposes. If no support is provided then the artery and pulses remain indistinct. For this reason palpation of the Chi positions often results in a pulse that is felt deeper or less strongly when compared to the pulse at the Guan positions. It is only after pressure is applied and the artery is supported by the bone that the pulse is felt distinctly. Sometimes the direction of finger pressure needs to be adjusted to ensure that the artery is being compressed into a firm surface, such as the tendons located medially to the radial artery. (This may account for the traditional description of the pulse at this position, the Kidney pulse, being located like a ‘pebble at the bottom of a stream’ or described as ‘insects crawling around the bone’.)

The Cun pulse positions are in a depression between two bony structures. These structures are the styloid process and the scaphoid bone. For this reason, the pulse and artery are less supported at the Cun position than at the Guan position, but are felt more distinctly than the Chi positions because of the stabilisation offered to the artery by these bones. However, as at the Chi position, the lack of direct underlying support under the cun positions often means the pulse and artery are not felt as distinctly at the Guan position, but are not as deeply located as the Chi position.

When taking the pulse the practitioner should sit opposite or next to the patient. Using the tips of the fingers (Box 5.3), the practitioner’s left hand is used to feel the pulses of the patient’s right hand and the practitioner’s right hand is used to feel the pulses on the patient’s left (Box 5.4). Similarly, if the practitioner were to palpate their own pulses on the right wrist, the practitioner’s left hand wraps under the wrist with the index, middle and ring fingers sequentially falling on the three pulse positions Cun, Guan and Chi. This is reversed if feeling the left hand pulses. This ensures that the same fingers are always used to palate the same pulse positions (Fig. 5.4). For example, the right index finger is always placed on the left Cun position, irrespective of whether the practitioner is palpating someone else’s pulse or their own. This will assist in ensuring that a level of sensitivity and a reference range of pulses are built up for that particular finger and this in turn assists with reliable identification and assessment of any changes in the pulse parameters at the related pulse site.

Box 5.3

Fingertips and fingernails

• The fingertips are the most sensitive regions of the finger. Individuals who play the guitar will find that the skin thickens at the tips of the fingers and for this reason, sensitivity to the pulse is often substantially lessened, if not absent. In such instances the finger pads rather than the tips should be used for assessing the pulse.

• The length of the fingernails can also prevent the use of the fingertips for pulse assessment. In such circumstances, the finger pads can be used or the nails regularly trimmed.

Box 5.4

• The fingers of the right hand are used to palpate the left wrist pulse.

• The fingers of the left hand are used to palpate the right wrist pulse.

5.5. Assessing the parameters

Once the pulse positions are located, the fingers are moved in different directions and depths to assess the pulse wave and the anatomy of the arterial wall at each of the positions. In particular, discrete increments of pressure are applied by the fingers to feel the three levels of pulse depth. The fingers are also moved from side to side to assess the width and tension of the arterial wall, and longitudinally to assess pulse length. Of the three movements, depth assessment is particularly important in CM, as each pulse site can be further divided into different levels of depth with each level theoretically reflecting a different region of the body.

Assessment of pulse depth is discussed in greater detail below, and this requires a specific technique to locate the levels of depth. Lateral and longitude assessment of the pulse are respectively discussed in Chapter 6 in the section on assessing the pulse parameter length and in Chapter 7 in relation to assessment of the pulse parameter arterial wall tension.

5.5.1. Relevance of the different pulse positions

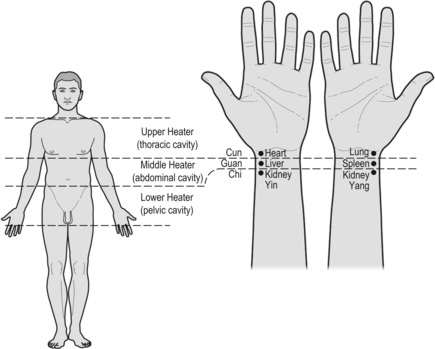

In CM, each of the three pulse positions is used to assess the overall pulse, as is done in biomedical practice, but each of the three positions is also viewed as reflecting a specific function or region of the body. Because of this, the pulse at each position is sometimes viewed as three distinctly different pulses, in spite of the three pulse positions being located on the same arterial segment and with the same blood flowing through them. The Cun positions are often ascribed to the upper region of the torso, the thoracic cavity, and changes in the pulse specifically at these two positions (the left and right Cun) indicate dysfunction of this region. Similarly, the Guan and Chi positions are ascribed respectively to the abdominal and pelvic cavities and the pulses are said to infer the function of these regions. The thoracic, abdominal and pelvic cavities are termed the upper, middle and lower Heaters (or Jiao) respectively. The pulse positions Cun, Guan and Chi also are simultaneously assigned to different channels, organs or regions of the body depending on the system used for interpreting the pulse information. In this sense then, the left Cun position for example is associated with the Heart and Small Intestine channel, the anatomical region of the chest, as well as reflecting the upper Jiao when paired with the right Cun position (Fig. 5.5). Besides associating each position to specific organ and channel entities, the three pulse positions are used for assessing the overall pulse qualities. These qualities include specific changes in the pulse wave and arterial structure that often occur across the three positions and are used to infer the nature of an illness and the effect it is having on the body.

|

| Figure 5.5Association of the three pulse positions to the three regions of the body and their relationship to the organs. |

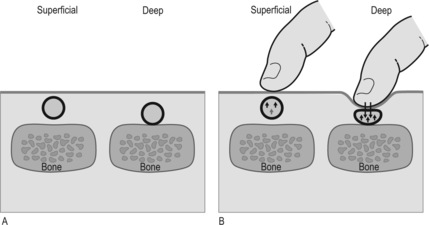

A consistent technique for correct location of the levels of depth is just as important in pulse diagnosis as correct anatomical location of the Cun, Guan and Chi pulse positions. Each pulse/position site can be further divided into two levels (superficial and deep) of depth or three (superficial, middle and deep), depending on the theoretical CM model used. For example, in Five Phase pulse diagnosis, only the superficial and deep levels of depth are assessed (Fig. 5.6). In determining overall pulse qualities as presented in the Mai Jing and Bin Hue Mai Xue, three levels of depth are often required for pulse assessment. There are even systems of pulse assessment based on the writings of the Nan Jing that palpate up to five levels of depth, and other systems state up to eight levels of depth (Hammer 2001), but these systems are not widely used. There are three commonly used levels of depth: superficial, middle and deep.

|

| Figure 5.6Radial artery, the pulse and assessment of pulse depth. The pulse depth relates to either the physical presence of the artery situated superficially or deep (A) or can be classified by the degree of finger pressure required to feel the strongest pulsation between the three levels of depth (B). Two examples are shown. One where the pulse is strongest at the superficial level of depth the other where the pulse is felt strongest at the deep level of depth. |

The parameter of pulse depth may be interpreted in two ways. Firstly, it refers to the level of depth where the radial arterial pulsation is found to be the strongest, regardless of the overall intensity of the pulsation. That is, we need to determine the relative strength of each level of depth. An integral part of determining pulse depth involves examination of the effect on radial pulsation of differing amounts of pressure exerted on the radial artery.

Secondly, pulse depth can refer to the level of depth at which the radial artery is physically located. This may be the result of anatomical structural variations within the subcutaneous layer of tissue overlying the radial artery, or the anatomical variations in the musculature and tendinous insertions around the forearm and wrist area. Diagnostically, the level of depth may be affected by pathological processes occurring within the body, resulting in either a pulse that can be felt strongest at the superficial or deep level of depth, or perhaps equally strong at all three levels of depth. Other factors affecting where the pulse can be felt include the strength of cardiac contraction.

5.6.1. Locating the three levels of depth

The three levels of depth should always be examined during pulse taking to determine the level at which the pulsations are strongest overall. This process is repeated as many times as necessary to correctly identify the strongest level. This is achieved by using consistent pressure across all three fingers to palpate to each of the three levels of depth; the superficial level of depth initially, followed by the deep and then middle levels of depth. Pulses at the three depths are found as follows.

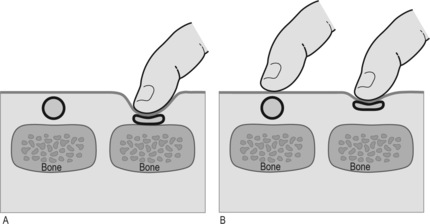

• Deep: This level of depth is found by occluding the radial artery (pressing the artery firmly against the radial bone) and then releasing the pressure gently until the pulse can be felt again. (The Mai Jing states ‘press to the bone and then release the pressure’ to feel this level of depth; alternatively, the pressure required is greater than the weight of 12 soybeans (Wang, Yang trans 1997).) This approach creates an initial rush in the blood flow when pressure is released slightly after occluding the pulse. A few seconds should be allowed to enable the pulse to equalise before assessment. It is important to take care not to release so much pressure as to move the fingers into the middle level of depth (Fig. 5.7).

|

| Figure 5.7Compression of the artery by finger pressure to assess the ease of pulse occlusion. In (A) compression of the artery occurs only when heavy pressure is applied by the finger, where the bone provides a stabllising support against which to occlude the artery. In (B) the artery is easily compressed at a more superficial level because of the lack of arterial pressure due to vacuity (deficiency) patterns of Qi or Blood. |

Note: With some pulses it may seem extremely difficult to occlude the artery, with the pulse still felt beyond Chi. When this occurs, it is not a failure to occlude the pulse but rather it is the continuing presence of pulse waves moving from the heart to the periphery and hitting into the side of the palpating finger. When pulses are detected on the side of the finger during pulse occlusion, this is usually a sign of strength in the pulse. Whether the pulse strength reflects health or illness requires further assessment. When enough pressure is applied to stop movement of the pulse under the fingers then the pulse is considered to be occluded whether or not the pulse continues to be felt at the side of the ring finger.

• Middle: This level of depth is found by applying a moderate pressure to the radial artery (not sufficient to occlude it), somewhere between superficial and deep. It is detected by exerting more pressure than required to palpate the superficial level but not enough to occlude the pulse. The middle level is located after initially locating the superficial and deep levels, which are found first in order to ascertain the amount of pressure required to palpate to the middle level. This level is an estimate of the halfway point between the two pulse depth extremes.

The order of finding the levels of depth is important to ensure that assessment is occurring at the correct level of depth. It is relatively easy to observe whether assessment is occurring at the superficial level of depth but difficult to locate the middle level of depth, located at the ‘halfway mark’, without first knowing the degree of strength required to find the deep level. As the pulse taker moves from the superficial level to deeper within the pulse, believing that they are at the deep level of depth, they may in fact only be in the middle level of depth. This can occur because no baseline has been established to give a context to both the middle and deeper levels of depth.

5.6.2. Defining a pulse by the level of depth

Different pulses are often described as being felt strongest at a particular level of depth. When a pulse is described as being located at the deep level of depth this can mean one of two things:

• The pulse is felt strongest at this level of depth; it may still be felt with less finger pressure at the other levels of depth, superficial and middle, it is just less strong

• The pulse cannot be felt at middle or superficial and only felt at the deep level of depth.

In these scenarios, the level of depth of a pulse is the level at which the pulse is felt strongest. Several pulse qualities are defined or identified in this manner. For example, the Floating pulse is defined by the fact that it is felt strongest at the superficial level of depth and sequentially less at the other levels of depth when finger pressure is increased. In this way the Floating pulse is determined not only by the presence at the superficial level of depth but also by its diminishing strength at deeper levels. With other pulse qualities, too, it is both the presence of strength at one level of depth and the absence of strength or a detectable pulse at another level of depth that is used for identifying that particular pulse. Another example is the Scallion Stalk (Hollow) pulse which is also felt strongest at the superficial level of depth and is absent at the middle and deep level of depth when further finger pressure is applied. (Note, however, that for the Scallion Stalk pulse other parameters in addition to depth assessment are of equal importance in defining the pulse.) The level of depth where the pulse is felt strongest is also often the level of depth where the arterial wall and pulse contour are clearly felt as well.

5.6.3. Diagnostic meaning of the levels of depth

5.6.3.1. Superficial and deep level of depth

In a CM context a pulse felt strongest at the superficial level of depth is broadly categorised Yang and a pulse felt strongest at the deep level of depth is categorised Yin. When the fingers move from the superficial to the deep level of depth, so the pulse progressively moves from reflecting Yang to reflecting Yin. This is reversed when palpating from the deep to the superficial levels of depth, when the pulse progressively reflects Yang.

If the pulse is viewed from an anatomical or pressure wave perspective, then the superficial pulse indicates an artery located near the skin surface or a pulse with sufficient force for the flow wave to expand the blood vessel. A pulse felt strongest at the deep level of depth can also indicate either an artery obscured by the skin and overlying tissue, or an artery with insufficient support, or simply a pulse that is strongest at the deep level. This may reflect a poor pulse force, which does not allow the flow wave to expand the vessel; and this may be due to a poor heart function or dilution of pulse strength through other factors such as arterial dilatation (see Chapter 2). The vessel wall can also constrict or be compressed by the surrounding connective tissue, restricting clear expansion of the pulse wave. From these examples, it can be seen that probably a number of different mechanisms are involved in the formation of a deep pulse. However, irrespective of why a deep pulse occurs, a pulse felt strongest at the deep level of depth is broadly categorised as Yin. The Eight Principles (Ba Gang) approach to pulse assessment in particular categorises pulse in this way, categorising a pulse as either Yin or Yang.

5.6.3.2. Meaning of the middle level of depth

Located between the deep and superficial levels of depth, the middle level of depth can be viewed from a CM perspective as the point of interchange between Yin and Yang, the fluxing between the two ‘poles’ of form (deep level) and function (superficial level) (Box 5.5). When the pulse is felt strongest at the middle level of depth this is viewed as a sign of balance between Yang or function (Qi) and the interplay with Yin or form (Blood). The middle level of depth is where the pulse should be felt strongest on most individuals. When the pulse is felt strongest only at the superficial or only at the deep levels of depth then this more than likely reflects ill health, dysfunction or maybe a prognostic sign inferring ill health. In this scenario, a pulse occurring strongest at the superficial level of depth reflects Yang-type illnesses or conditions that have caused Yang to become hyperactive. This is seen in cases of febrile conditions producing delirium, or in conditions with dream-filled restless sleep. Similarly, a pulse occurring strongest at the deep level of depth reflects Yin-type illnesses or conditions that have constrained or depleted the Yang, causing the pulse to contract into the deeper regions of the artery. Yin conditions often involve organ dysfunction.

Box 5.5

• Superficial level of depth reflects Yang: exterior

• Deep level of depth reflects Yin: interior

• Middle level of depth reflects the balanced interplay between Qi (function) and Blood (form)

In their simplest form, the overall CM pulse qualities in the literature are used in this context, identifying the nature and location of an illness, whether Yin or Yang. In this way, the superficial level of depth reflects the Yang, the middle level of depth the action of Qi with Blood, and the deep level of depth the organs/Yin.

5.6.3.3. Combining depth assessment with the other parameters

Through additional procedures and techniques for assessing the pulse wave and arterial wall, the practitioner combines the information derived from depth assessment for better understanding of the pulse (Box 5.6). The cumulative end to this process is combining the assessment of the different pulse aspects or parameters of the pulse wave and arterial structure in the identification of the traditional overall CM pulse qualities. However, not all individuals will present with a distinctly identifiable CM pulse quality as described in the CM literature. In these situations assessment of the parameters individually can be critical to using the pulse to inform diagnosis and treatment. These CM pulse qualities and the associated parameters that define them are discussed in detail in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7.

Box 5.6

Other circumstantial information gained from the process of pulse palpation

• Finger nails: Is there any cracking or deformity in the fingernails? Observe the colour of the nails and nail bed. A pale colour indicates poor circulation and can be related to blood vacuity. A bluish colour can indicate hypoxia and relates to poor lung and cardiac function. White indicates complete vasoconstriction.

• Skin: Feel the temperature and texture of the skin and flesh overlying the artery. Is the skin warm, cold or clammy? Is the skin texture rough, indicating dryness, or soft, indicating fluid retention?

• Wrist size: Observe the size of the wrist to make a judgement on whether the arterial width is appropriate. Is the artery proportional to individual’s body size?

• Veins: Observe the colour and shape of the veins. Can they be easily observed? Are they distended (indicates stagnation or increased arterial pressure)? Are they blue, green or red in colour?

• Radial artery: Is the artery easily observable? Are there visible pulsations? A visible artery can indicate an increase in arterial tension while visible pulsations indicate pulse force or a superficially located pulse.

5.7. The normal pulse

The normal pulse is a template used to identify variations in the pulse from an expected health range. Given that the pulse is a manifestation of the interaction of several different parameters, it is logical to also consider the normal pulse as a range of values within which the pulse can present and still be considered a reflection of health. For example, the normal pulse rate ranges from 60 to 90 bpm.

Yet the normal presentation for one pulse parameter does not necessarily exclude the potential that another pulse parameter is simultaneously presenting abnormally. For example, a pulse rate of 70 bpm is considered healthy, within the normal range, but when accompanied by increased arterial tension, where the arterial wall becomes hard, then the pulse is not normal. When determining whether the pulse is normal or not, all aspects of the pulse therefore need to be considered.

There are a range of additional variables specific to the individual that also need to be given consideration when determining if the pulse is normal or not. They include body size, physique, exercise levels, age, gender and seasonal variables. In this sense, the normal pulse refers to an individual’s usual pulse.

5.8. Assessing health by the pulse

5.8.1. Shen, Stomach Qi and Root

In a CM context, a pulse is described by some contemporary authors as having three attributes or factors (Maciocia 2004, Townsend & De Donna 1990). These are Shen, Stomach Qi and Root.

• Shen: This refers to the relative strength of the pulse, which has a constant rate and regular rhythm. The Shen is used in this sense to refer to physical heart function: the parameters associated with the strength of pulsation and regularity of heart contraction. It represents the functioning of Qi of the Heart. Assessment of this attribute or factor should occur at any level of depth and any position. What constitutes healthy and unhealthy presentation of the parameters for this pulse attribute is discussed in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 in the discussion on pulse rate, pulse rhythm and pulse force.

• Stomach Qi: This refers to the rate of rise and decline in the blood flow wave as it passes under the fingers, where the contour of the pulse reflects Stomach Qi. The attribute or factor refers to adequate levels of Qi and blood and their interaction. There is an obvious relationship to dietary factors and adequate intake of appropriate food to produce blood and Qi. Ni’s (1995) translation of the Nei Jing states that the Yang pulses reflect the health of the Stomach Qi. Pulses lacking strength, arterial expansion and are short are therefore classified as Yin or as pulses which lack Stomach Qi (p. 30). This relates to the blood quantity filling the artery and sufficient Qi to motivate blood expansively.

• Root: This is used to refer to the Kidneys (assessed at the Chi pulse positions) or assessment of the Kidneys at the deep level of depth across all three positions. (The association of the Kidneys with the deep level of depth is discussed at length in the Mai Jing .) The concept is used to refer to a pulse with foundation. That is, there should be at least some presence of the pulse in the deeper levels of the artery. This is not always the case with certain illnesses, but in health, presence of Root means the Yin is anchoring the Yang. In this way, a pulse overly strong at the superficial level of depth indicates the lack of Yin anchoring the Yang.

Of the three concepts, the Root is of most importance. The Shen level may be transient and more affected by moment-to-moment changes than the other two levels. Poor sleep will result in decreased strength at the Shen level, yet the Root should remain unaffected. The Root reflects the foundation of health in the body. As long as the Root is present then prognosis is good, as it is when the pulse has a regular rhythm and a constant strength.

When the pulse rhythm, strength or contour begins to fluctuate, whether from moment to moment, or within the same individual over a longer period of time, then the outlook is indicative of potential and/or actual dysfunction.

5.8.2. Parameters and a healthy pulse

Assessment of a healthy pulse from a parameter perspective is assessed on four aspects. These are:

• Timing of the pulse

– Rate: 60–90 bpm

– Rhythm: Regular

• Presence of the pulse

– Depth: Felt at all three levels of depth but relatively strongest in the middle or deep level of depth

– Length: Felt at the three pulse positions Cun, Guan and Chi, and/or beyond Chi

• Arterial structure

– Width: Appropriate to the individual’s physique and the circulation reaching the periphery to warm the skin, toes and fingers

– Arterial tension: There should be some tensile strength in the arterial wall, but it should be capable of being externally indented when moderate finger pressure is applied, or internally expanded by the arterial pulse wave

– Pulse occlusion: With increasing finger pressure the pulse should be felt at least at two levels of depth before being occluded. Pulsation on the body side of the ring finger is likely to be present when occluded

• Pulse waveform

– Force: Pulse hits the fingers with strength with a distinct rise and fall in the pulse amplitude — pulse rises against the fingers

– Contour and flow wave: Smooth uninterrupted flow.

The idea that the superficial level of depth reflects Yang and the deep level of depth reflects Yin is used to associate a particular channel and organ to each of the pulses found at these two levels across the three positions. In particular, the three positions of each wrist at the superficial level of depth are said to reflect the functional strength of the Yang channels and organs. In the deep level of depth, at the corresponding positions, the pulses are considered to reflect the functional strength of the Yin channels and organs. This gives a total of 12 pulse positions: 6 located superficially and 6 deep.

There are various arrangements of the organs or channels at the wrist pulse positions that have been described in the CM literature in the past. Variations in arrangement of the organs and channels are discussed extensively in many texts and are not repeated here. However, listed below are two most commonly used arrangements which are relevant to contemporary clinical practice. Each of these arrangements is described in the Nan Jing and Bin Hue Mai Xue . The first relates to the arrangement of channels, the other to the organs. The channel arrangement at the wrist pulse positions is often used in acupuncture, while the organ arrangement at the wrist positions is often described for use in herbal medicine. There is also a third arrangement that blends aspects of the acupuncture channel and herbal organ arrangements together. These distinctions can be further described as follows:

• Acupuncture channel arrangement: So called because of the association of the small intenstine (SI) and large intenstine (LI) pulses at the superficial level of depth at the left and right Cun positions. In this arrangement the SI partners the Heart (HR) channel and the LI partners the Lung (LU) channel. The Yin and Yang pairing of the fire and metal elements is complete, as represented in the LI/LU and SI/HR channels being located together on the upper limbs. Acupuncture affects the channels and so the arrangement reflects the channel location in the body (Table 5.1).

| Left side | Superficial | Deep | Deep | Superficial | Right side | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small intestine | Heart | Cun | Lung | Large intestine | ||

| Gallbladder | Liver | Guan | Spleen | Stomach | ||

| Bladder | Kidney | Chi | Pericardium | Triple Heater | ||

| Yang | Yin | Yin | Yang |

• Herbal organ anatomical arrangement: This places the SI and LI respectively at the superficial regions of the left and right Chi positions. This is done as the SI and LI organs are located in the lower regions of the body and so the pulse arrangement of the organs at these positions reflects this arrangement. This model is often explained by the focus in herbal medicine on organic disease. Herbs traditionally interact with the organs (Table 5.2).

| Left side | Superficial | Deep | Deep | Superficial | Right side | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest | Heart | Cun | Lung | Chest | ||

| Gallbladder | Liver | Guan | Spleen | Stomach | ||

| Small intestine | Kidney (Yin) | Chi | Kidney (Yang) | Large intestine | ||

| Yang | Yin | Yin | Yang |

Secondary English sources of the classics further distinguish the Kidney pulses in the Bin Hue Mai Xue model, with the Kidney pulse on the Left side reflecting Kidney Yin and the Kidney pulse on the right side reflecting Kidney Yang. The division of the Kidney pulse in this way appears to be a contemporary adaptation. For example, Birch (1992) in his literature review on radial pulse positions notes the division of the pulse into Kidney Yin and Kidney Yang as not occurring in the classical pulse literature he reviewed, whereas secondary English translations often denote this division.

5.10. Comparison of the overall force of the left and right radial pulse

In addition to the techniques for locating the pulse positions and different pulse depths, pulse assessment and some associated theoretical pulse assumption systems require examination of the relative differences in pulse strength, irrespective of the actual degree of strength or overall force in the pulse. Whether a pulse is forceful or forceless is irrelevant when assessing relative strength differences, as assessing relative differences in strength is achieved by:

• Comparing one position to another position (within and between different sides)

• Comparing one level of depth to another (also within and between different sides)

• Comparing the overall pulse on the left with the right side pulse

• Comparing the pulse of one individual to another.

5.10.1. Comparing left and right pulses

Comparisons are made by simultaneously palpating the left and right radial pulses. In making a comparison, all three positions on each wrist are palpated using an even pressure. All three of the levels of depth need to be evaluated consecutively. For example, at the superficial level of depth the practitioner assesses the overall strength of the pulse when palpating the Cun, Guan and Chi positions simultaneously. This procedure is repeated at the middle and deep levels of depth. The overall strength at all three levels of depth is then averaged to arrive at the strength for the left and right side pulse. To exclude a dominant hand bias due to better discrimination skills depending on whether the practitioner is left or right hand dominant, the subject should be asked whether the pressure exerted by the assessor on each side’s pulse is felt as equal. If necessary, the finger pressure is adjusted and then the pulse on each side should be examined at each of the levels, simultaneously. In this approach, pulse assessment primarily focuses on the parameter of force. Chapter 9 discusses a number of assumption systems where pulse diagnosis focuses primarily on assessing relative differences in strength.

5.11. Pulse method

A pulse method is a systematised approach that puts together the pulse procedures into an organised examination process. This includes:

• Deciding whether pulse diagnosis is an appropriate technique to use

• When to take the patient’s pulse in the consultation

• Order of gathering information from the pulse

• Interpreting the information within a diagnostic context.

5.11.1. Is pulse taking appropriate?

Like all examination techniques used in the diagnostic process, pulse taking is not always required, nor necessarily an appropriate assessment method to use in all situations. Take the case of an acute sprained ankle. Pulse assessment of the radial arterial pulse is not likely to contribute any significantly useful information when determining the extent and level of damage sustained to the ankle, or meaningfully inform treatment protocols for the acute presentation of this condition. In contrast, pulse diagnosis is considered necessary for assessing the functional state of the channels and related organs in Five Phase or constitutional acupuncture.

Pulse diagnosis is viewed in the literature at one extreme as a technique that can be used for diagnosing any condition and used in all situations, through to the other extreme where it is useful only for assessing heart function. The decision to incorporate pulse into diagnosis into the examination process therefore rests largely with the consulting practitioner and relates to their personal views and perception of health, their education, practise of CM and experience.

Situations derived from the various views of authors where pulse diagnosis is considered an appropriate assessment technique to use generally include:

• Disorders affecting the organs and their related functions

• Dysfunction in the movement, production or storage of Qi, Blood, Essence and Fluids

• Problems associated with the emotions

• Psychological based illnesses including some forms of addictive behaviour and substance abuse

• Management of long-term illness and dysfunction.

Pulse diagnosis sits within the four examination approaches of CM. These include questioning, observation, listening/smelling and palpation, including pulse diagnosis. In CM, there is no strict order of obtaining this information. In spite of this, there are divergent opinions on the appropriate time during consultation to feel the radial pulse. One view is that pulse should be undertaken at the beginning of consultation, while the other viewpoint states the reverse, claiming it should be undertaken at the conclusion of consultation after the other examinations have been completed. Each viewpoint has a valid rationale and this is often based on the perceived value that pulse assessment contributes to the examination process.

• At the beginning of the consultation: Assessment of the pulse at the beginning of consultation allows the practitioner to get a general overview of what is happening in the body, without being influenced by too much additional information. Obviously once the patient is seen, visual diagnostic information is already being processed; the way they move, talk, breathe, the colour and condition of the facial features and skin, the hair, expression, eyes and general demeanour of the patient. This, in conjunction with the information obtained from pulse diagnosis, will also help to direct the practitioner along the diagnostic process. When using pulse assessment at the beginning of consultation the practitioner needs to guard against assessing increased pulse rates due to any exertion undertaken by the patient before the consultation. If pulse is taken at the beginning of consultation, it is advisable that the patient be left to rest before pulse assessment commences.

• At the end of consultation: The end of the examination process is often when radial pulse diagnosis takes place, often as a confirmatory process, to further corroborate what the other signs and symptoms have already revealed. However, taking pulse at this stage can present problems: there is the danger of trying to fit the assessed pulse pattern into the diagnosis determined by the other diagnostic processes such as questioning, looking and listening. At this stage of consultation, it can be argued that it is easy to ignore certain characteristics that do not fit in with diagnosis, or to perceive changes that do not really exist. This may especially occur when a specific CM quality is not clearly present in a definitive form. (By using the pulse parameter system, we can take into account the various degrees of all changes that are occurring within the pulse.)

Despite the two contradictory views there are some general guidelines regarding the appropriate time to take the pulse.

• When the patient has rested and introductions have been made (make sure the heart rate is not effected by extensive conversation, exertion, exercise or prior movement).

• Use pulse diagnosis at the beginning of the assessment process rather than at the end to ensure that the reading is not being biased by other information.

• If pulse diagnosis is used as an adjunctive or confirmatory diagnostic tool, then pulse at the conclusion of questioning may be appropriate, bearing in mind that pulse assessment at this stage may be influenced or biased by prior findings through other means of assessment.

• It is important to remember that the patient may provide responses to questions that are contradictory, or they may be elusive. In this case, the pulse may give a better indication as to what is occurring than the patient’s answers. Questioning can be guided by the pulse findings, and at least used to gain a better perspective in broad terms about what may be occurring.

• Consuming food will disturb the pulse. Assessment should therefore occur at the end of the consultation if the patient has eaten beforehand.

5.11.3. The order of gathering pulse information

Once it is established that pulse assessment is appropriate and when to take the pulse, the practitioner then needs to use a methodical approach in gathering the information by pulse assessment.

This will assist with:

• Analysing the pulse for purposes of systemic comparisons

• Establishing a routine which will lend itself to heightened focus when assessing pulse

• Ensuring that all aspects of the pulse are assessed and none are missed.

It should be clearly noted that there are a number of different methods described in the literature, and different practitioners will inevitably favour one approach over another. Some practitioners also develop their own methods to gather information about the different parameters of the pulse. There is no right or wrong approach to gathering the information. However, the practitioner should always aim to develop a consistent method for pulse assessment.

Stage 1: initial impressions

Step 1: Locate the pulse positions and place the fingers on these

Step 2: Feel the overall pulse with all fingers on the three pulse positions Cun, Guan and Chi

Step 3: Feel the overall pulse at the other levels of depth.

Stage 1 is about overall impressions of the pulse, so it isn’t strictly necessary to locate the three levels of depth exactly. Rather, simply move the fingers towards the bone, occlude the pulse and gently raise the fingers back towards the superficial level of depth.

When arriving at an overall impression of the pulse it is useful to consider the following questions:

• Is the pulse easy to find?

• Is the pulse felt clearly?

• Are there any distinct or unusual presentations of the pulse and related parameters? That is, is the pulse noticeably superficial, or is there noticeable tension in the arterial wall?

• Is the pulse strong, weak or of normal strength?

• Does the pulse have a contour or does the arterial wall dominate?

• Does the pulse rebound against the finger when pressure is released?

• Do your first impressions correlate with the individual’s physical build and apparent state?

• Does the pulse feel fast or slow? (Note that this initial stage of assessment is about your first impressions of the pulse and it is not necessary to actually take the actual measure of pulse rate at this stage).

When first feeling the pulse it is important not to be swayed by your first impressions into making a premature diagnosis. When feeling the pulse, what often occurs is that a particular change in one of the pulse parameters is quickly apparent when illness is present. For example, there may be an increase in arterial tension, or the pulse is noticeably strongest at the superficial level of depth, or pulse force is greatly reduced or pulse rate increased. In this instance caution must be used not to classify the pulse into a CM pulse quality based on the most apparent change in the one parameter alone. For example, it would be easy to call any pulse that has an increase in arterial tension a Stringlike (Wiry) pulse. This would be incorrect, as there are several distinctive pulse qualities that all manifest with an increased in arterial tension and the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse is simply one of these. Also, the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse is associated with changes in other pulse parameters and not simply based on arterial tension alone. If a pulse is forcibly classified into one of the overall qualities, then important information is lost that can mean the difference in making a correct diagnosis and formulating appropriate treatment.

Stage 2: specific pulse assessment; the parameters

Next, it is necessary to palpate and make an assessment of the presentation of each specific parameter. Start with a measured assessment of pulse rate, using a watch, and then determine whether the rhythm is regular. Rate and rhythm are the easiest of the parameters to assess. This makes them useful for focusing the mind for assessment of the other parameters. Next assess the other parameters in the following order:

• Depth: At which level of depth is the pulse felt strongest?

• Length: Is the pulse long or short?

• Width: Is the pulse thin or not thin?

• Force: What is the overall force of the pulse? How does the strength vary between positions and at different levels of depth?

• Pulse occlusion: Is the artery easy or hard to occlude?

• Arterial wall tension: Is this increased, normal or absent?

• Contour and flow wave: Are there any changes in the contour and texture of the flow wave?

By following a set of procedures and methods in this way, the practitioner is able to build a diagnosis based on the pulse by adding the assessment of one pulse parameter to another. As a picture of the parameters builds up, it may become apparent that the parameters are presenting in such a way that they form one of the traditional CM pulse qualities described in the literature. However, if the pulse parameters do not combine to form an easily identified pulse quality, this need not be a cause for concern. Often, the pulse doesn’t present as described in the literature, so assessing the individual aspects or parameters of the pulse, such as depth, width and length, is still just as informative. Table 5.3 is a summary of the parameters listed in Stage 2 and gives a diagnostic context of the parameter and related changes within a CM framework when using the parameters in this way.

| Description | CM theory | How the pulse is affected | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | Level of depth at which the pulse can be felt the strongest | May indicate:

1. Where disease is located. The superficial level generally refers to external, while deep refers to internal

Yang Qi’s ability to move outwards

The strength of Yin Qi and its ability to anchor Yang Qi

|

A pulse felt strongest at the deep level and unable to be felt superficially can indicate:

1. Deficiency of Qi and Blood

2. Obstruction of Qi and Blood

A pulse felt strongest at the superficial level of depth can indicate:

1. External attack

2. Floating of Yang Qi due to deficiency of Yin (Yang loses the anchoring effect of Yin) Width Diameter of the artery

|

| Width |

Diameter of the artery

The area that the arterial wall displaces laterally on the palpating finger

|

Can indicate a number of factors:

The volume of Yin fluids and Blood

Relates to the arterial tension

Affected by Damp

|

Increased width:

Hyperactivity of Yang: Yang excess disturbing Qi and Blood, causing them to expand and fill the artery

Floating of Yang due to deficiency of Yin not restraining Yang, whose nature is to move outward and upward

Lack of volume to fill artery pulse feels ‘hollow’, easily occluded

Decreased width:

Deficiency of Yin fluids or Blood

Damp can compress the arteries

|

| Rate | Number of beats per minute | Functional activity of Yang Qi |

Increased rate: hyperactivity of Yang or relative hyperactivity of Yang due to deficiency of Yin

Decreased: deficiency of Yang or excess Cold

|

| Rhythm | Interval between beats: should be regular | Indicates the state of Heart Qi and functional activity of the organs | Irregular rhythm may occur at irregular or regular intervals. The more often they occur, the more severe the condition |

| Length | Presence or absence of pulsations at Cun, Guan, Chi, beyond Cun and beyond Chi |

Indicates:

Amount of Qi and Blood

Presence of heat

Obstruction of Qi and Blood

|

Hyperactivity of Yang: Yang excess disturbing Qi and Blood, causing them to expand and fill the artery |

| Arterial tension |

The tone of the arterial wall, giving it definition. Related to the elasticity of the arterial wall.

Contributes to the feeling of “hardness” of the artery wall when palpated

|

Reflects the activity of Yang Qi

May reflect the presence of pathogenic Cold

|

Hyperactivity of Yang Qi can lead to increased tension in artery wall

Decreased activity of Yang Qi can lead to decreased tone of arterial wall, leading to less definition

Stagnation of Qi, whether due to vacuity or repletion may cause increased tension

Pathogenic Cold may cause contraction of the arterial wall leading to increased tension

|

| Force | The intensity with which the pulse strikes the palpating finger |

Reflects the functional activity of Yang Qi

Reflects volume of Blood/Yin fluids

May reflect presence of a pathogenic factor

May reflect strong Zheng Qi (antipathogenic Qi)

|

If Yang Qi is deficient, the pulse will be forceless, due to lack of motive force to propel blood. Deficiency of Blood/Yin fluids: less fluid being propelled and filling out the artery, therefore forceless If the pulse is forceful, this may indicate:

Strong functioning of Yang Qi, or

May indicate obstruction of Qi and/or blood

Presence of pathogenic factor that has entered the body

|

| Pulse occlusion | Refers to the amount of pressure needed to occlude the radial pulse | Influenced by the pulse force, volume, width and arterial tension |

If the blood volume is decreased the pulse may feel ‘empty’. If there is sufficient Qi and blood, then pulse may require force to occlude

If Yang Qi is hyperactive causing stagnation, increased tension in the pulse can make it difficult to occlude. A lack of Yang Qi to provide the arterial wall with tone may lead to easy occlusion

|

| Flow wave | Refers to the longitudinal movement of blood through the artery |

Reflects the quality and volume of blood

Also related to amount of Yang Qi, providing pulse with impetus to move

|

Hyperactive Yang Qi due to stagnation of Qi can cause blood flow to be restrained

Deficiency of Blood/Yin fluids can cause blood flow to become turbulent

If Yang Qi is deficient then blood flow is less forceful, may be slower

|

| Pulse contour | Refers to the texture of the blood flow and shape of the pulse |

Related to Yang Qi controlling the tone of the arterial wall

Also related to volume of blood

|

An increase of fluid within the system leads to an increase in force and rounded contour

If blood is deficient, the pulse force will vary in intensity, unable to fill the vessels

If Yang Qi is hyperactive and the arterial walls are less flexible then arterial walls don’t expand and contract as readily

Damp in the tissues may compress the arteries, leading to a narrowing of the arteries (less able to expand normally)

|

Information pertaining to the specific assessment of the pulse parameters in Stage 2 above is given in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7, along with a system of diagnostic interpretation of assessment findings, including the related traditional CM pulse qualities. This chapter has focused on the technique required to locate the positions and levels of depth for assessing the parameters. Other techniques for assessing length, width, pulse occlusion, strength and contour are included with the appropriate parameters to which they relate in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 as well.

5.12. Other considerations when assessing the pulse and interpreting the findings

In addition to the difficulties of applying different pulse assumption systems and pulse descriptions from the literature, the complexity of the CM radial pulse diagnostic process is heightened by other factors that must be taken into account when evaluating the pulse according to the patient’s individual characteristics and environment (Maciocia 1989). These include influences such as seasonal effects, gender, age, level of fitness, occupation and body type (Deng 1999, Maciocia 1989, O’Connor & Bensky 1981).

It has been assumed that these variables impact on the physiological presentation of the pulse, and therefore obviously have important implications for the interpretation of an individual’s pulse qualities. As a result, it is necessary to consider these factors when examining the pulse, to determine whether the pulse quality is appropriate for the individual rather than being caused by a pathological disturbance. For example, the Slow pulse in CM theory is usually associated with a Cold condition. However, if the patient is accustomed to regular exercise (such as an athlete) then a Slow pulse may be quite normal. What might appear to be a pathological pulse, when taken in the proper context and in the absence of any other abnormal signs and symptoms, could be considered to be normal for the individual in question.

The following discussion on factors affecting the radial pulse is reproduced and modified with permission from King (2001).

5.12.1. Radial pulse assumptions in classical and modern CM literature

Contemporary CM texts have a tendency to accept the classical pulse information, often incorporating the term ‘traditionally’ to qualify their material. Frequently there is little reference to the actual sources from which this information was obtained. This creates problems in terms of placing the information in a historical perspective and identifying the theoretical framework being utilised. In addition, this makes it difficult to determine whether (and if so, where) the modern authors have expanded on the information, adding their own commentary. In some instances, CM texts mention that the pulse varies with age, gender and body weight, but neglect to elaborate on how these factors affect the pulse characteristics.

Despite the effects that such factors are believed to have on the pulse, such claims remain untested and continue to appear unchallenged in many contemporary CM texts. As such, we have presented these factors as a summative collection of information from the relevant literature.

5.12.2. Seasonal effects

The philosophical theory of Yin and Yang, on which Chinese medical theory is based, is thought to have evolved as a result of observing cycles occurring in nature. This theory, which proposed that all phenomena exist as a result of the variable interaction of opposite but complementary qualities, could be seen in the cyclical nature of day and night, the tides and seasonal changes.

The human body was seen as a reflection of the universe, a microcosm within the macrocosm, and therefore subject to the cyclical effects of nature. Health was dependent on living ‘in accord with nature’ (Ni 1995: p. 53). This interaction of human beings with their surroundings meant that changes in the environment were believed to be capable of affecting the individual. The effect of the environment on the body is discussed at great length in the Nei Jing . Different climatic circumstances resulted in different type of diseases. The seasons influenced the type of illnesses that occurred, where they occurred within the body and the way that treatment was conducted.

The weather … affects every living creature in the natural world and forms the foundation for birth, growth, maturation, and death

The cycles of heaven and earth reflect in the constant changes in nature. Take the example of seasonal weather changes … Every organism in nature adapts and changes along with the seasonal cycles of germination in the spring, growth and development in the summer, maturity and harvest of the autumn, and storing or hibernating in the winter. The human pulse also corresponds to these changes

In particular, the effect of the four seasons on the pulse has been noted a number of times, with descriptions of the qualities that the pulse reflected in each season.

In the spring, the pulse will mirror nature and become slightly wiry or round; in the summer, it will enlarge and become flooding; in the fall, the pulse will float to the surface; in the winter, it will sink to the interior.

The relationship between the eight winds and four seasons, the flow between one season and another, will all determine the normal pulses in the body.

As a consequence, when diagnosing it was necessary to take the normal seasonal variations of the pulse into consideration.

In both the classical and modern texts, there is some agreement concerning the presence of seasonal variations in pulse. These changes generally relate to the depth and quality of the pulse. For example:

These [seasons] influence the pulse, it being deeper in Wintertime and more superficial in Summertime

The human body is subject to influence by climatic changes over the four seasons … These changes are reflected on the pulse. During spring the tension of the pulse gradually increases and becomes wiry. During summer … the pulse overflows (like a hook). During autumn … the pulse becomes empty, floating, soft and fine (like a hair). During winter … the pulse becomes deep and strong

(Li, Huynh trans 1985: p. 8).

In the spring … the tension of the pulse is enhanced and the wiry pulse appears; in the summer … the pulse will be fully filled and thus a full pulse presents; in the autumn … a pulse that is felt soft, light and floating, like a feather of a bird, occurs; in the winter … Yang Qi of the human body also hides in the depth or the interior of the body, causing the pulse to be deep and very forceful. No matter how the pulse changes, as long as the changes correspond to the seasons and are felt forceful and unhurried, it is a normal pulse

In moderate climates, the regular change of the seasons and their typical weather produces slight inflections of the pulse on healthy individuals which may be described in spring as an inflection in the direction of a stringy pulse, in summer … a flooding pulse, in autumn … a superficial pulse and in winter … submerged pulses … Yet none of these inflections, taken in isolatedly, may be interpreted as a symptom of disease

In The Practical Jin’s Pulse Diagnosis, a modern Chinese pulse text utilising a pulse diagnostic system based on a combination of CM and biomedical knowledge, the influence of seasonal change is still acknowledged. Changes in the pulse are attributed to physiological changes in the body coping with the extreme changes of temperature through the four seasons. For example, the pulse is ‘deep and solid’ in winter and ‘full … strong when it rises and weak when it sinks’ in summer, as a result of the body’s attempt to regulate its temperature (Wei, Lu (trans) 1997: p. 108). Elsewhere in the text, changes in the rate of the pulse are noted in winter (slow) and summer (rapid), while the spring pulse is said to be slightly wiry.

The wiry pulse, which is strong, thick, hard and wiry, is often felt in the spring; the full pulse, which is felt strong when it rises and weak when it sinks, is usually seen in summer … in autumn … the pulse is often felt full and feather-like in shape; and in winter, the pulse is usually deep and solid …

Rapid … in summer … slow … in winter’

5.12.2. Gender

The notion of a gender-based difference in pulse strength has persisted from early CM teachings. Statements regarding the comparative strength of men and women’s pulses can be found in many classical and modern CM texts. This includes various differences in the strength of the left and right hands, in the relative strength of the Cun, Guan and Chi positions and an overall difference in strength (and sometimes pulse quality) between genders.

The difference in strength according to gender appears to have its basis in Yin—Yang theory. According to this theory, the left side of the body is considered Yang and the right side Yin. Males should have more Yang energy, therefore males should have a stronger left side. Women, being associated with Yin, should have a stronger right side. This follows for the difference in the relative strength of the positions. In Yin Yang theory the upper position, equated with Cun, is Yang and the lower position, equated with Chi, is Yin. Therefore, in men the Cun position should be slightly stronger than Chi and vice versa for women.

The Nei Jing, one of the oldest extant Chinese medical classics, devotes a number of chapters to the methodology, pathology and significance of the palpation of arteries around the body. Differences in the pulse are noted in relation to pregnancy.

When examining the pulses, if one finds the Yin pulses are distinctly different from the Yang pulses, this indicates pregnancy

If in women the hand shaoyin or the heart pulse is prominent, pregnancy is indicated

The Nineteenth Difficult Issue in the Nan Jing introduces the concept of gender difference regarding movement of energy in the vessels throughout the body. Gender was to be taken into account when feeling the pulse to determine whether the pulse was normal. It was considered normal for a male pulse to be ‘stronger above the gate’ (corresponding to the Cun position) and in a female for the pulse to be stronger ‘below the gate’ (corresponding to the Chi position). Using this system, doctors could identify the gender of their patient by pulse alone. Patterns that would be considered normal in one gender would be, if found in the other, pathological.

In males [a strong movement in] the vessels appears above the gate; in females [a strong movement in the] vessels appears below the gate.

When males display a female pulse it is a sign of deficiency disorder within; when females display a male pulse it is a sign of a disorder of excess in the extremities

Differences in the overall force and qualitative aspects of the pulse are noted in relation to gender. The Mai Jing describes the differences in quality and strength between female and male:

The pulses in females are inclined to be more soggy and weaker than in males … For males, the left (pulse) being larger is favourable, while for females the right being larger is favourable’

Li Shi Zhen’s Pulse Diagnosis states:

The left is Yang and the right is Yin. Men have more Yang Qi … their left hand is stronger. Women have more Yin blood … their right hand pulse is stronger.

(Li, Huynh (trans) 1985: p. 4).

However, although this was disputed by Flaws (1995), a modern TCM author, in his book The Secret of Chinese Pulse Diagnosis, he neglects to elaborate further his own findings.

‘[Bin Hu says] … it is normal for men’s pulses to be larger on the left and women’s to be larger on the right. I have not found this to be the case in my clinical practice

This opinion was revised in a later edition of the same book:

Personally, I would say women’s pulses are smaller on the left, at least in the bar and cubit positions, due to their monthly loss of blood

In another translation of Li Shi Zhen’s classic, The Lakeside Master’s Study of the Pulse (Li, Flaws (trans) 1998) the relative strength of the Cun and Chi according to gender is discussed.

As long as the pulse remains normal in number of beats (and/or size and shape) throughout the four seasons, it is normal for a woman’s pulse to be sunken in the inch and a man’s pulse to be sunken in the cubit

(Li, Flaws (trans) 1998: p. 70 footnote).

A modern author in support of this view, stated that:

In men, the Front [Cun] position should be very slightly stronger, while in women the Rear [Chi] position should be so. This also follows the Yin-Yang symbolism according to which upper is Yang (hence male) and lower is Yin (hence female)

Alternatively, a ‘somewhat hook-like pulse’ is considered to be normal for everyone, with the pulse starting off deep in the Chi position and then rising to become relatively floating in the Cun position (Flaws 1997: p. 61). This would appear to correlate with the physiological positioning of the radial artery which is situated deeper at the Chi position and then becomes more superficially located due to support of the radial bone at Guan (refer to section 5.6.1).

Gender specificity in relation to pulse strength differences between right and left appears to be abandoned in some modern Chinese texts, with references instead to overall differences in strength. In particular, women’s pulses are generally said to be weaker and faster than men’s pulses:

In adult females, the pulse is usually softer and weaker than the males, because they have more fat covering the vessels and their constitution is relatively weaker than males.

In general, the pulse of men will be somewhat large and women will be relatively weak, slightly fine and somewhat fast.

Women usually have thready, weak and a little rapid pulse.

A woman’s pulse is usually softer and slightly faster than a man’s

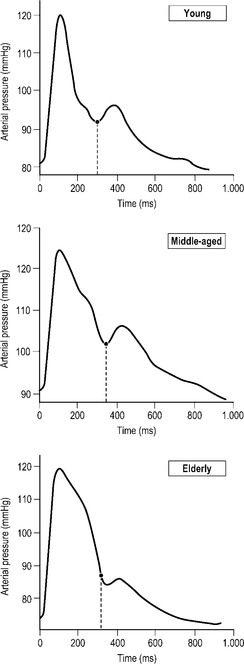

Contemporary Western CM texts tend to reiterate the traditional theory regarding left/right differences. O’Connor & Bensky (1981) state that women’s right sides are usually stronger than their left, while the opposite occurs in men. In addition, such pulse information is believed by some to be able to predict the sex of an unborn child, so that if the pregnant woman’s right side is stronger then the child is female and if the left is stronger, it is male.