Chapter 12 Genitourinary System

Kidney – Structure and Function

The kidney has several functions:

where:

where:

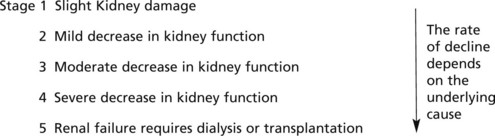

| CKD | Stage | eGFR/mL/min/1.73m2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | with an abnormality* | >90 |

| 2 | with an abnormality* | 60–89 |

| 3 | 30–59 | |

| 4 | 15–29 | |

| 5 | <15 |

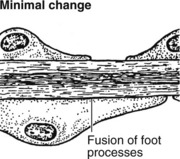

Glomerular Structure and Function

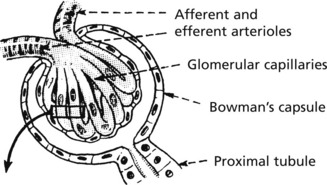

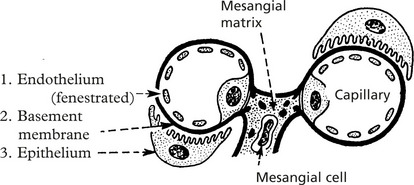

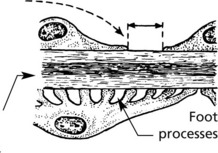

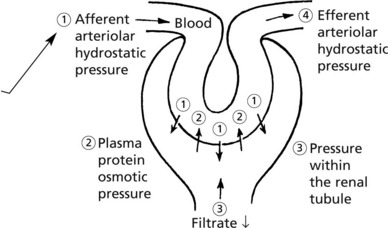

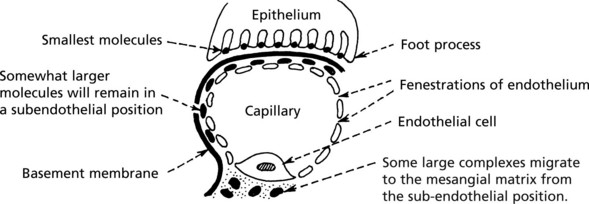

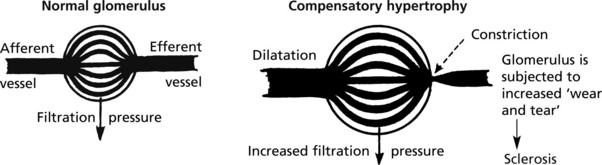

The glomerulus, of which there are over 600000 in the adult, consists of an invagination of a capillary network, derived from the afferent arteriole, into Bowman’s capsule – the beginning of the proximal tubule.

The glomerulus is an efficient filter due to the large surface area of the glomerular capillaries.

Glomerular Diseases

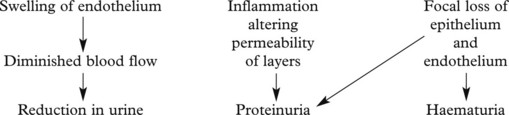

The mechanisms underlying these changes are as follows:

These lead to 4 main clinical syndromes:

The main forms of glomerular disease are described in the following pages.

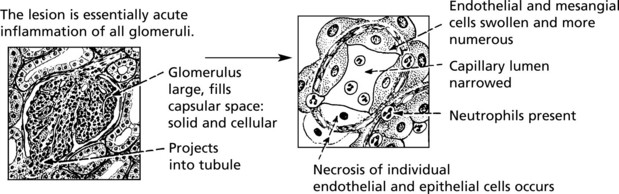

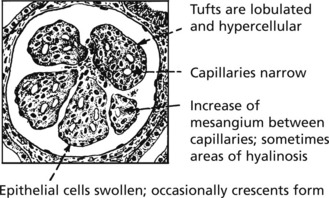

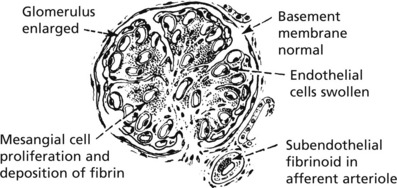

Acute Diffuse Proliferative Glomerulonephritis

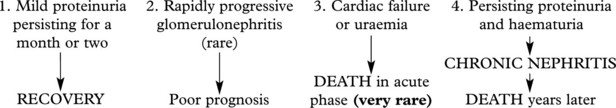

This disease classically follows 2–3 weeks after an infection – usually pharyngitis due to Group A haemolytic streptococci. It is commonest in children and young adults who develop the NEPHRITIC SYNDROME: oliguria, proteinuria, haematuria (urine is smoky and dark), moderate hypertension and facial (periorbital) oedema. This disease is now uncommon in fully developed countries.

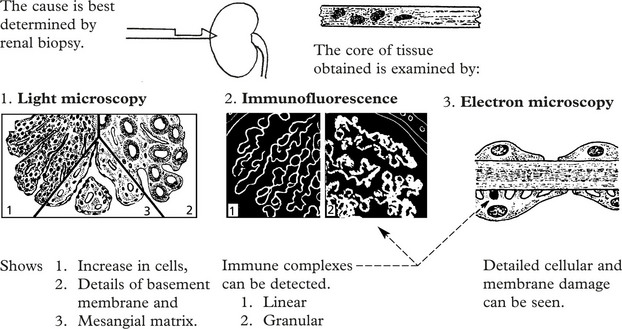

Immune complexes are identified by:

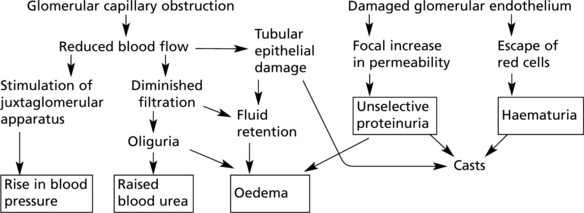

The clinical findings can be correlated with pathology as follows:

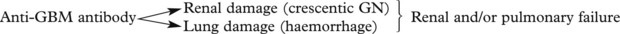

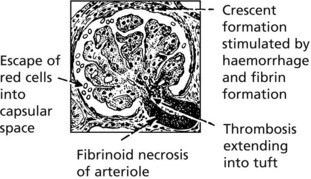

Crescentic (Rapidly Progressive) Glomerulonephritis

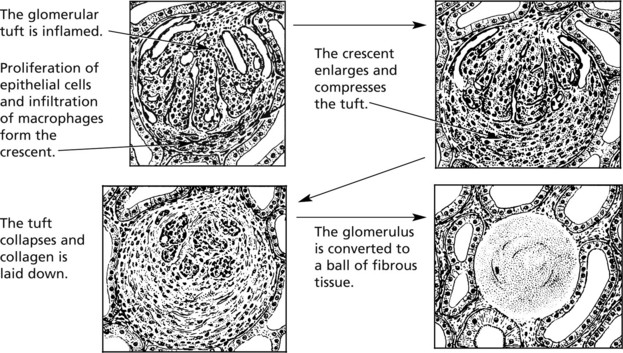

Without treatment, this disease progresses to end-stage renal failure in weeks or months. The histological hallmark is crescent formation in >50% of glomeruli.

Many types of glomerulonephritis can progress to crescentic GN. Examples include:

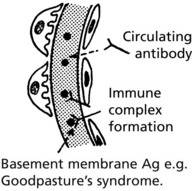

IF shows linear deposits of IgG and C3 in the capillary basement membranes

Prognosis – Without treatment, most patients die within 6 months.

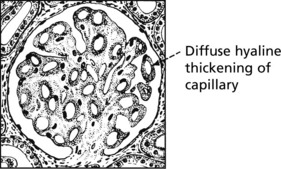

Membranous Glomerulonephritis

This accounts for around 30% of cases of the nephrotic syndrome in adults; some patients present with asymptomatic proteinuria.

Aetiology

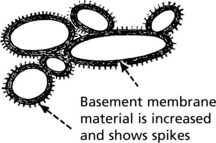

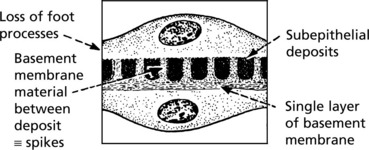

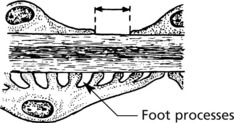

Pathology – There is generalised thickening of capillary basement membrane.

Specific silver staining of the basement membrane shows a typical pattern.

Immunofluorescence reveals deposition of IgG in the capillary walls.

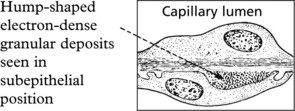

Electron microscope findings explain this appearance.

In the later stages there is a massive increase in basement membrane material.

Mesangiocapillary (Membranoproliferative) Glomerulonephritis

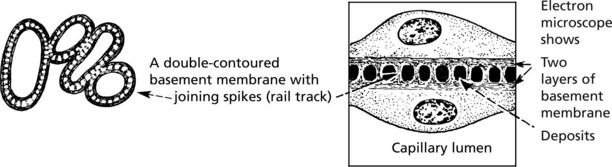

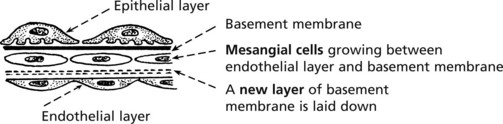

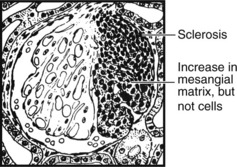

In this form of glomerulonephritis there is an increase both in cells and mesangial matrix within glomeruli.

Silver staining of basement membrane

Duplication of basement membrane as in membranous glomerulonephritis, but without spikes.

These changes are due to ‘mesangial interposition’

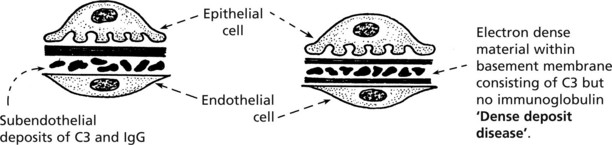

Using electron microscopy and immunofluorescence, 2 types are identified.

Focal Glomerulonephritis

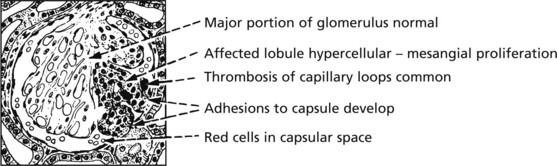

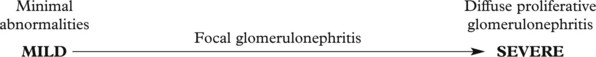

In contrast to the glomerular diseases discussed already, focal glomerulonephritis affects only a proportion of glomeruli (focal) and only part of those glomeruli (segmental).

The pattern is associated with haematuria or nephrotic syndrome. Segmental lesions heal by fibrosis.

IgA Nephropathy

This is the commonest form of glomerulonephritis worldwide. It can present with microscopic or macroscopic haematuria or the nephrotic syndrome and may lead to chronic renal failure. It typically affects young males, who often suffer recurrent episodes after upper respiratory infections although all ages can be affected.

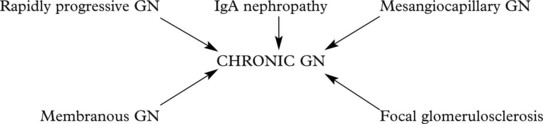

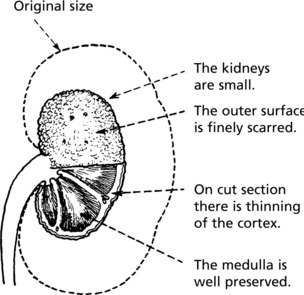

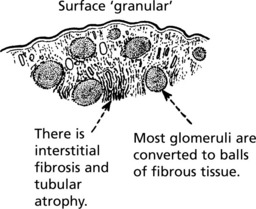

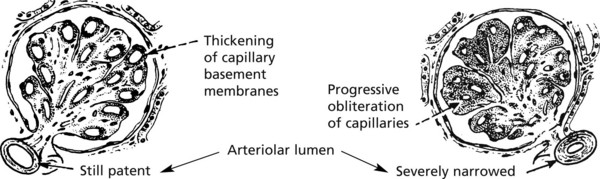

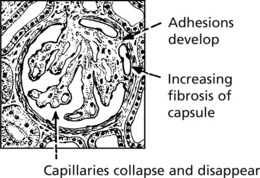

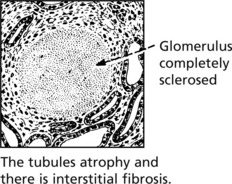

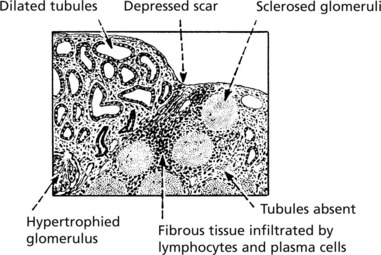

Chronic Glomerulonephritis (GN)

This is the end stage of many forms of glomerulonephritis, but most patients present at this stage without a history of previous renal disease.

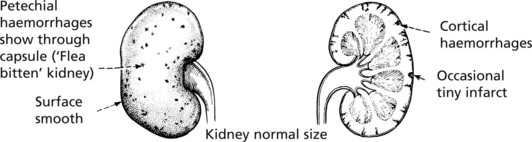

Pathology The kidneys are both small – granular contracted kidney.

Glomerulonephritis – Disease Mechanisms

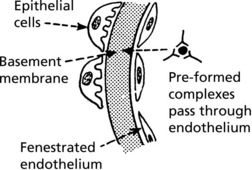

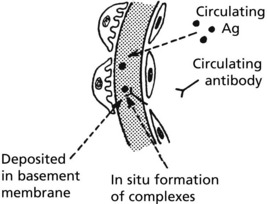

The mechanism in most forms of GN is:

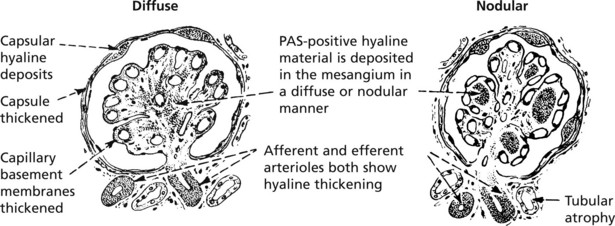

Glomerular Disease in Systemic Disorders

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

At least 50% of patients with SLE have clinical evidence of renal involvement, and almost all will have abnormalities on renal biopsy.

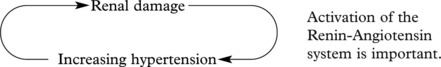

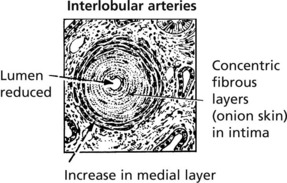

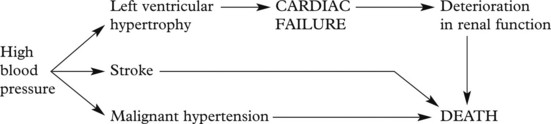

The Kidney and Hypertension

There are two aspects to the relationship of the kidney and high blood pressure.

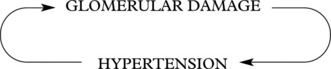

A vicious circle can be set up:

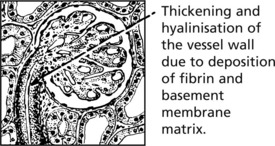

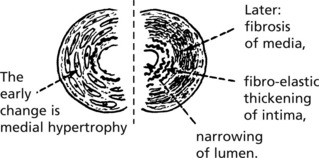

Benign Hypertension

These arteriolar changes lead to glomerular ischaemia.

These changes are patchy in distribution so that renal failure rarely occurs.

It is now thought that small emboli from atheroma of the aorta are responsible for much of the scarring in benign hypertension.

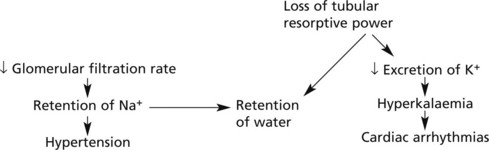

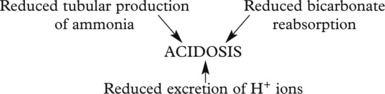

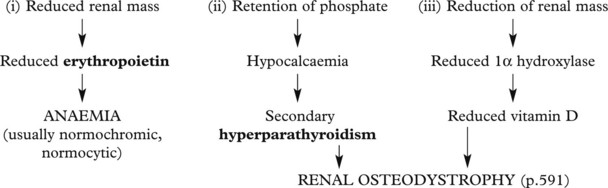

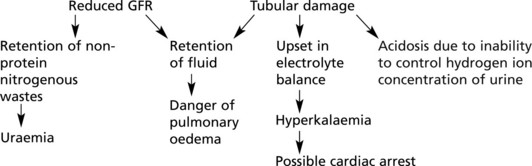

Chronic Renal Failure

Progressive renal damage in many kidney diseases eventually leads to chronic renal failure. The major causes include:

In many cases the underlying cause cannot be determined.

Infections of the Kidney and Urinary Tract

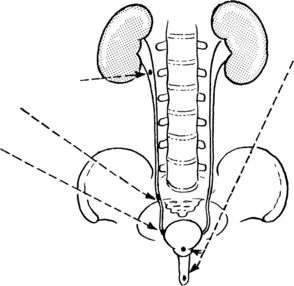

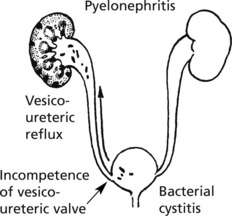

The kidney can become infected through 2 main routes.

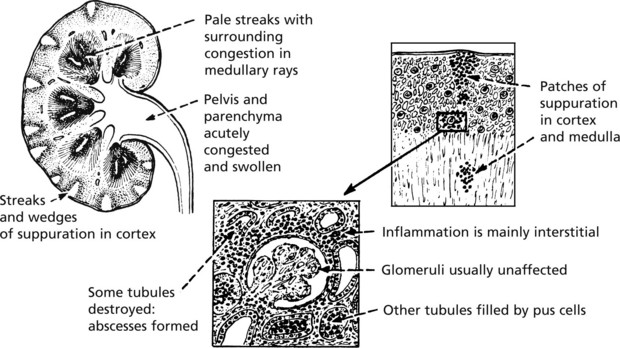

Acute Pyelonephritis

Causes

In women, cystitis is common, particularly in the sexually active. Ascending infection is often provoked by vesico-ureteric reflux during micturition. Pyelonephritis is common in pregnancy.

In men, urinary tract obstruction is usually found, typically due to prostatic enlargement.

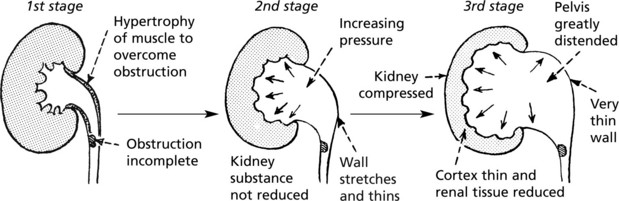

Influence of Urinary Tract Obstruction

Obstruction of the urinary tract acts in 3 ways to promote infection:

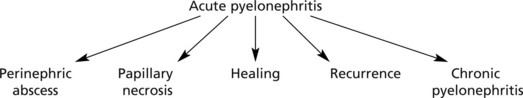

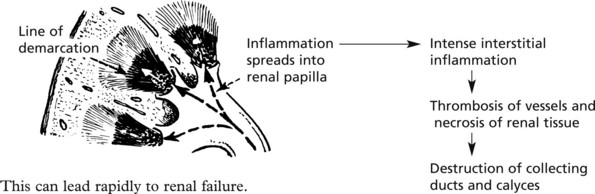

Progress The possibilities are as follows:

Perinephric abscess and papillary necrosis are now rare due to specific antibiotic therapy.

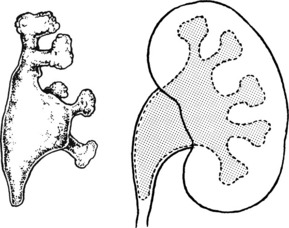

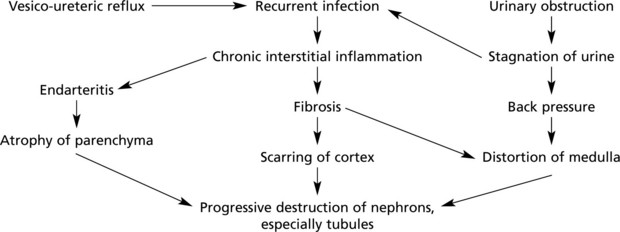

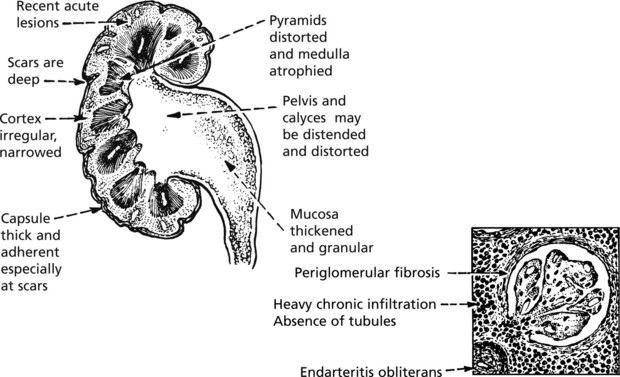

Chronic Pyelonephritis

Chronic pyelonephritis is essentially the result of repeated attacks of inflammation and healing. Vesico-ureteric reflux in early life, often associated with congenital anomalies of the urinary tract, is now regarded as important. The process can be visualised as follows:

Microscopically, there is interstitial fibrosis, inflammation and loss of parenchyma.

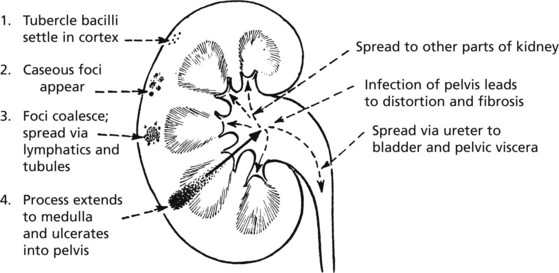

Tuberculosis of the Kidney

Uncommon in many Western countries. It is due to blood spread of infection from another site, e.g. the lungs. Even less commonly, there may be an ascending infection from some other part of the genitourinary system, e.g. epididymis.

Intercurrent Renal Conditions

Renal Function and Pregnancy

Four conditions affecting renal function may arise in pregnancy.

EM examination shows mesangial deposits of fibrin, fibrinogen, IgM and complement.

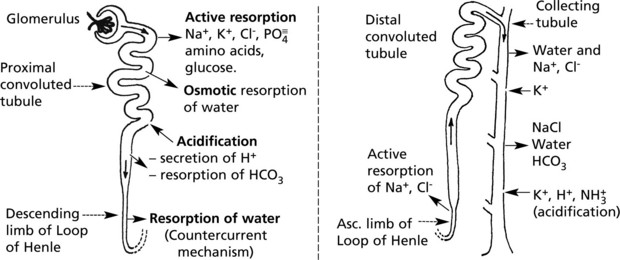

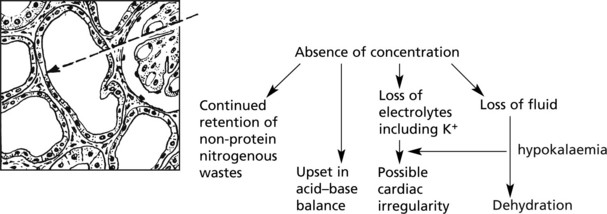

Renal Tubule – Structure and Function

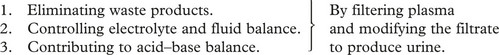

The renal tubules modify the glomerular filtrate. Initially isotonic and neutral, it becomes hypertonic and quite strongly acid. Within 24 hours, 180 litres of filtrate are reduced to 1.5 litres of urine. The main functions of this process are:

Three mechanisms are involved:

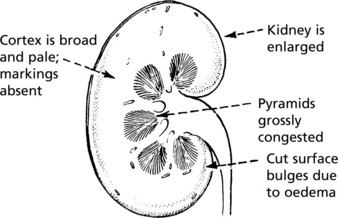

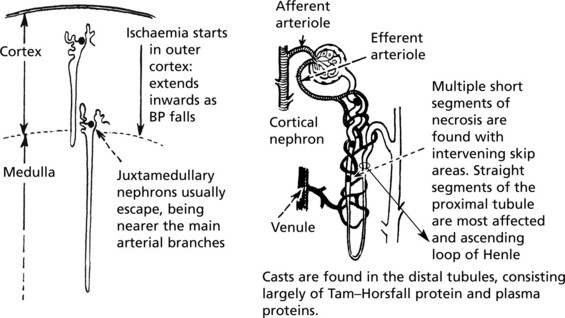

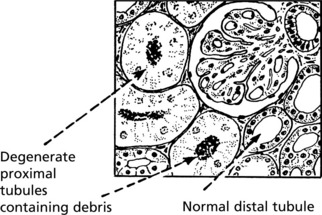

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) (Acute Tubular Necrosis)

This arises in 2 circumstances:

Acute Kidney Injury (Acute Tubular Necrosis)

Toxic AKI

The lesions are evenly distributed, affecting all nephrons. They are maximal in the proximal tubules and are the direct result of the toxin, the action of which is intensified by the concentrating activity of the tubule.

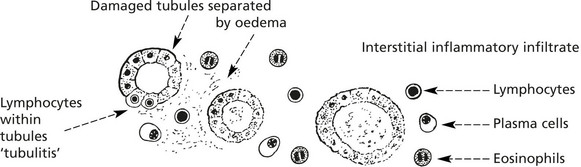

Tubulo-Interstitial Diseases

In this group of disorders there is damage to the renal tubules and to the interstitial tissues. The main forms are:

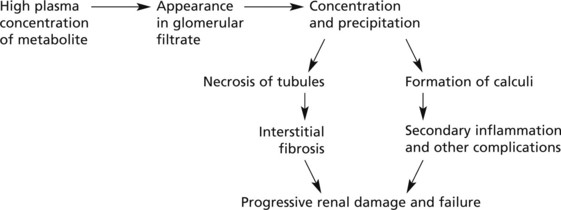

Metabolic Tubular Lesions

These are due to metabolic defects.

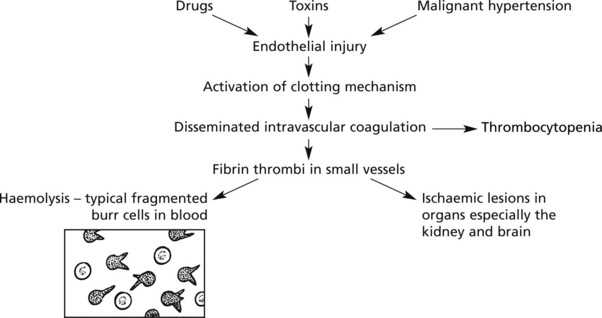

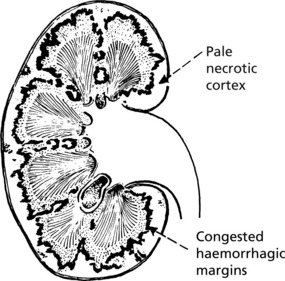

Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome)

Pathological Complications of Renal Replacement Therapies

The prognosis of end-stage renal failure has been greatly improved by (1) Dialysis and (2) Renal Transplantation. The following possible pathological complications are important:

Congenital Disorders

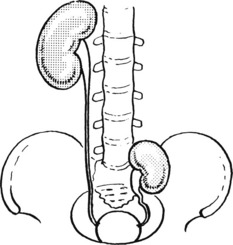

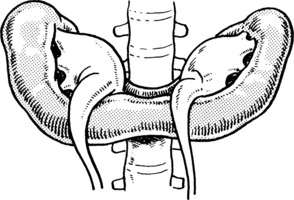

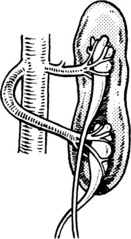

There are many forms of malpositions and malformations of the kidney:

One or both kidneys fail to reach the normal adult position. The condition causes difficulty:

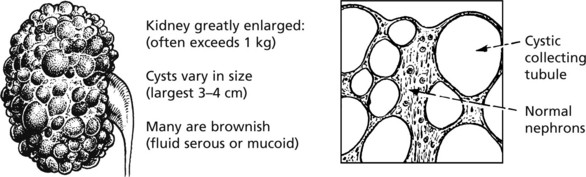

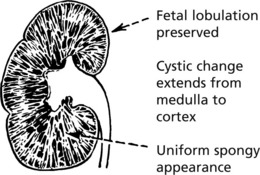

Polycystic Kidney Disease

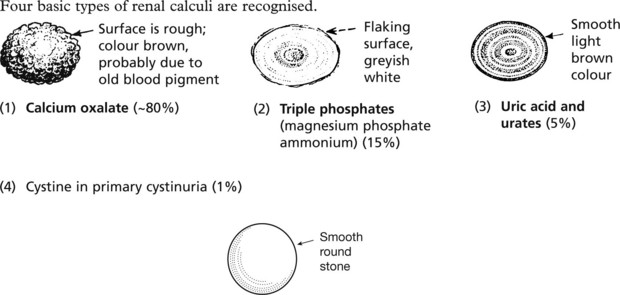

Urinary Calculi

Stones may form in the renal pelvis, ureter or bladder.

Commonly the stones are mixed.

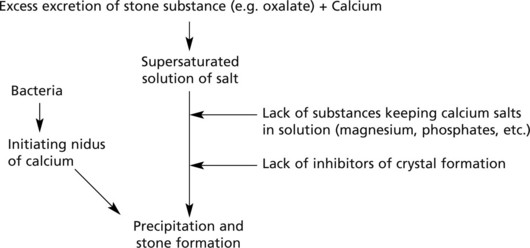

Mode of formation. There are two steps – nucleation followed by aggregation:

Predisposing Factors

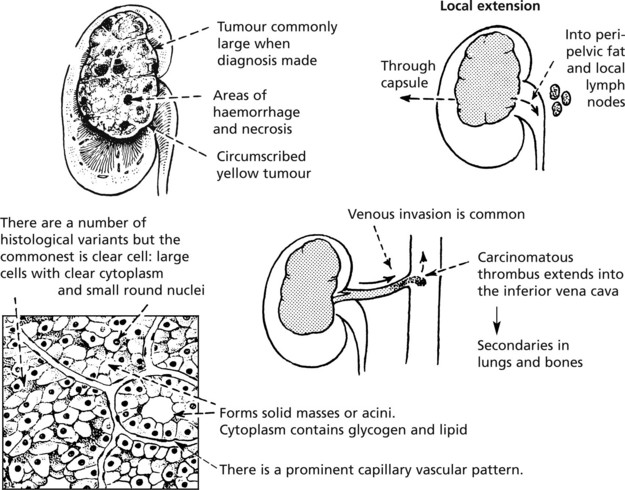

Tumours of the Kidney

Malignant Tumours

Three are of importance: renal cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma and nephroblastoma.

Systemic Effects

Patients with renal carcinoma may have:

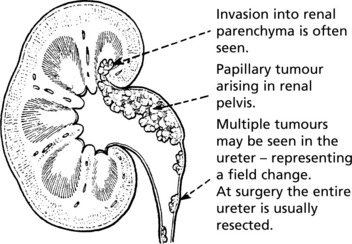

Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis is discussed on p.483.

Diseases of the Urinary Tract

The urinary tract is a collecting and discharge system. There are 4 main pathological processes affecting its function: (1) obstruction, (2) infection, (3) calculus formation and (4) neoplastic disease.

Urinary Tract Infection

Acute Cystitis

The bladder shows the usual signs of inflammation. Small haemorrhages are common in the oedematous mucosa. The causes have already been discussed.

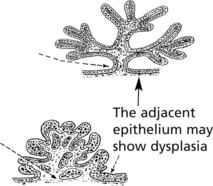

Tumours of the Urothelium

Transitional Cell Carcinoma

This tumour arises from the epithelium of the renal pelvis and is similar to the commoner transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, with which it shares aetiological factors.

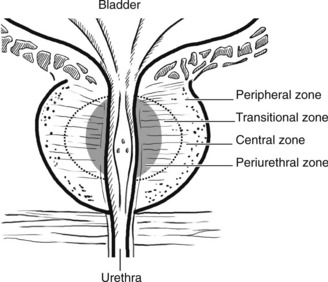

The Prostate

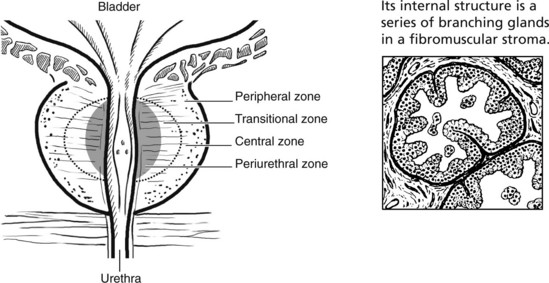

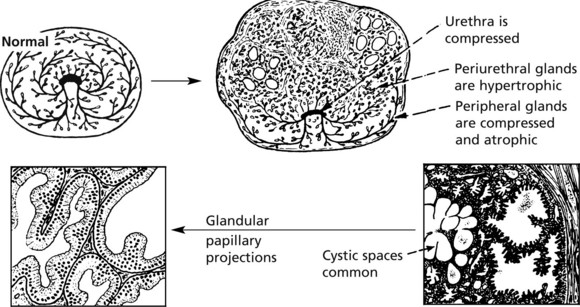

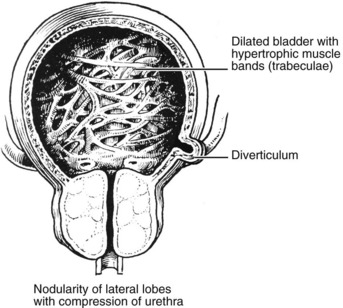

The prostate surrounds the bladder neck and urethra. Although traditionally divided into five lobes, it is now regarded as having four major zones, which tend to be affected by different disorders.

There are three main disorders of the prostate:

Prostatitis

Diseases of the Prostate

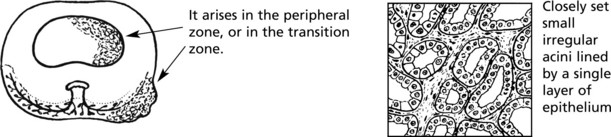

Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate

This is now the commonest cancer in men in the UK and a significant cause of cancer death. It is rare below the age of 40 and rises to very high prevalence in men over 80.

Spread

Biochemical Tests

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), analogous to CIN (p.503), has been recognised as a pre-invasive stage of the disease. High grade PIN is strongly associated with development of invasive cancer.

Diseases of the Penis

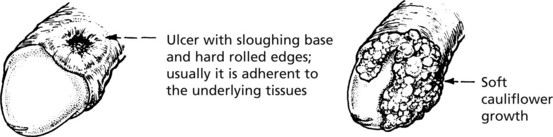

Tumours of the Penis

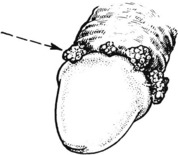

Papillomatous proliferations (condylomata acuminata), usually arise in the coronal sulcus or glans. They are due to sexually transmitted infection by Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Types 6 and 11, and are analogous to similar lesions in the female genitalia

Diseases of the Testis

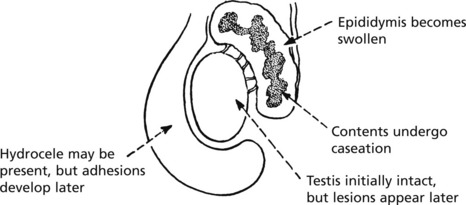

Epididymitis and Orchitis

Acute inflammation due to bacteria is uncommon in these organs. Spread of urinary infection via the vas deferens does occasionally occur and may result in suppuration. Gonorrhoea and chlamydia are seen in young men.

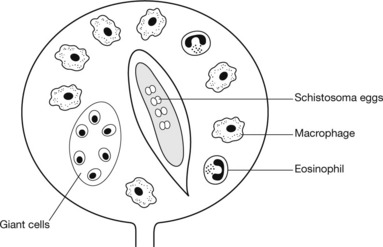

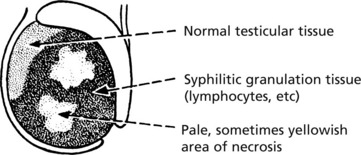

Chronic inflammations are important, although rare, in this region.

Tumours of the Testis

Germ Cell Tumours of the Testis

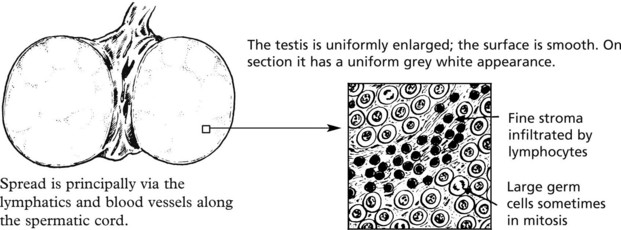

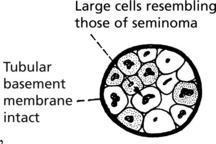

These tumours make up 2% of cancers in men and the incidence is rising steeply in Western countries. They are the commonest form of malignancy in young men. Tumours are more common in undescended testes.

The 2 main tumour types are seminoma and teratoma.

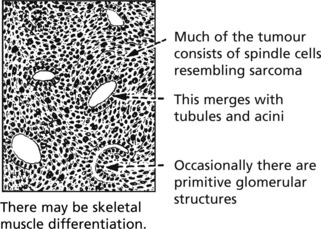

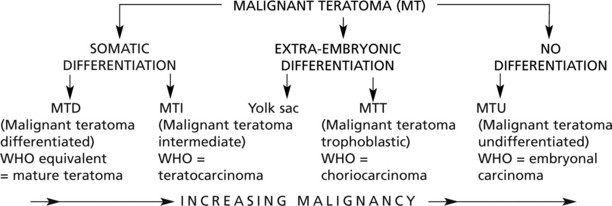

Malignant teratoma (non-seminomatous germ cell tumour)

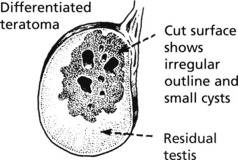

These tumours, unlike seminoma, are usually irregular in shape and show focal haemorrhage and necrosis: in the better differentiated tumours small cysts are common.

pages 463, 470, 471

pages 463, 470, 471