Chapter 13 Genioplasty

Summary

Introduction

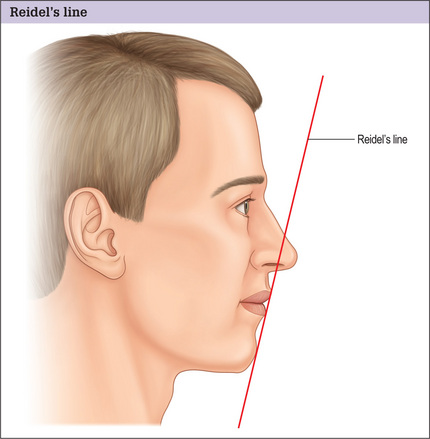

The chin is the lower topographic limit of the face and thus plays an important role in the perception of appropriate facial proportions.4,5 A vertically deficient or excessive chin places the lower third of the face out of balance relative to the middle and superior thirds of the face.6 Horizontal deficiency or excess diminishes facial pulchritude, most notably in profile (Figs 13.1 & 13.2). Additionally, the chin has a pivotal role as a reference in the appreciation of other facial features, most notably the nose. A large nose is often paired with a deficient chin and they have a reciprocally negative effect on the appearance of each other and on overall facial attractiveness (Fig. 13.3).7–9

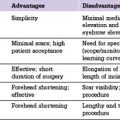

Improvements in the chin can be achieved by osteotomy or by the use of implants or grafts for augmentation.10 Osseous procedures include burr reduction (ostectomy), osteotomy with caudal segment repositioning, osteotomy with grafting or osteotomy with segmental sectioning.11–15 Augmentation genioplasty can be accomplished with autologous tissue grafts such as bone or cartilage or, more commonly, with alloplastic implants.16,17 The benefits of alloplastic augmentation include a shorter and less technically demanding procedure. However, alloplastic genioplasty can pose limitations in achieving large augmentation without causing lip retraction, has a lower success rate for correction of asymmetry and offers very limited potential to change the vertical dimension of the chin.18

Anatomy

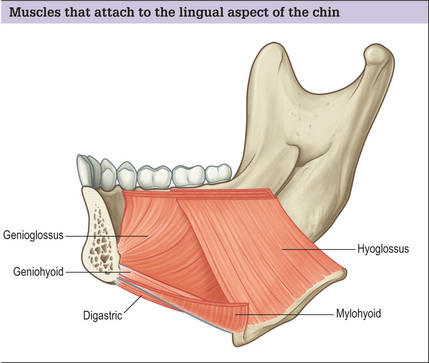

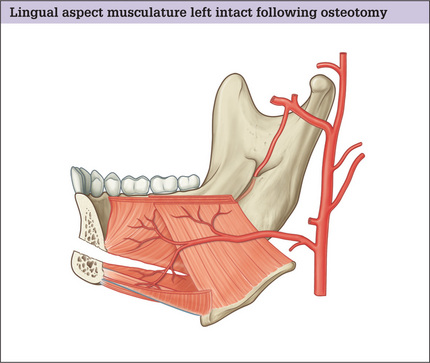

From external to internal, the layers of the chin include skin, subcutaneous fat, muscles, periosteum and bone. The depressor angularis, depressor labi inferioris and mentalis attach to the anterior plane of the chin. The geniohyoid, genioglossus, mylohyoid and anterior belly of the digastric attach to the lingual aspect. Following elevation of the anterior periosteum and horizontal osteotomy, the blood supply of the caudal chin segment is maintained via terminal lingual artery periosteal perforating branches that travel through the musculature attached to the lingual side (Figs 13.4 & 13.5).

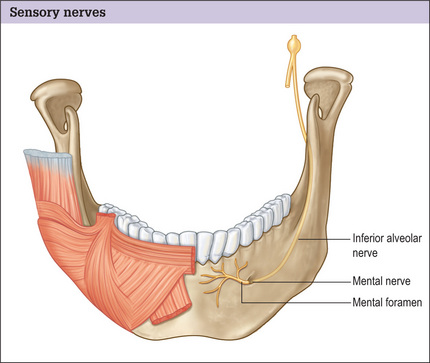

The mental nerve supplies sensation to the anterior mandibular gingiva, mucosa and lower lip. It is a continuation of the inferior alveolar nerve and exits the mandible via the mental foramen. The mental foramen is located in the vertical plane between the first and second mandibular premolars. In the terminal portion of its course, as it travels posterior to anterior, the nerve ascends to the foramen (Fig. 13.6). This upward trajectory must be understood when planning the location and angle of a horizontal osteotomy.19–21 In order to avoid direct nerve injury, the osteotomy should be placed at least 5 mm caudal to the foramen and be executed at a caudal-oblique angle.

Indications and Contraindications

The presence of some medical conditions influences the type of genioplasty that is prudent. Generally, patients with diabetes mellitus or immune deficiency are not ideal candidates for alloplastic augmentation.1,22 Patients over the age of 60 years old with a mild-to-moderate horizontal microgenia are better candidates for alloplastic augmentation. On most other patients osteotomy is preferred, although the use of implants is not considered inappropriate. Patients who smoke cigarettes are not the ideal candidates for the use of grafts as a chin augmentation material.

Preoperative History and Considerations

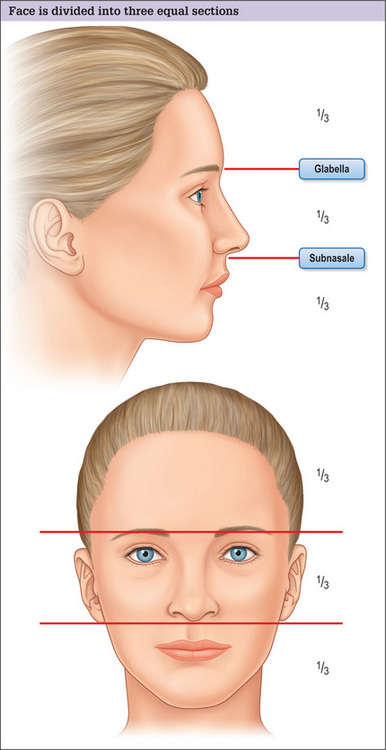

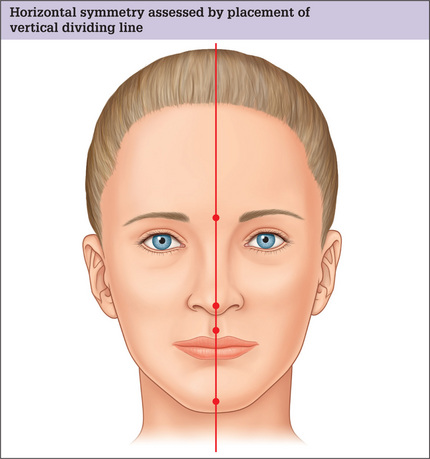

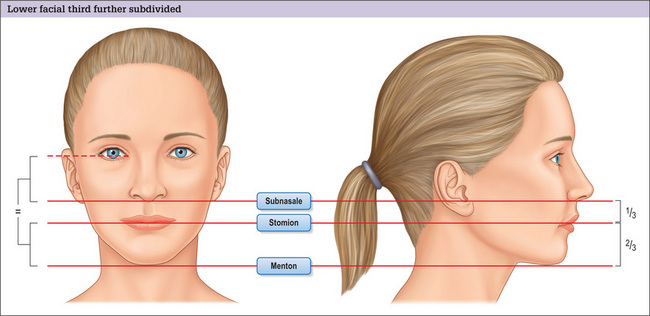

The cardinal determinants of chin harmony are its projection symmetry and vertical length. Assessment of the vertical dimension of the chin is performed first in frontal view analysis. The face is divided into two anatomic portions using imaginary lines placed at the eyebrow level and subnasale. The three segments that these lines create should be equal in the harmonious face (Figs 13.7 & 13.8).

The terminus of the female chin is a single light reflfection. In the male chin, there are dual light reflections indicating the underlying increased width and rectangular shape of the chin. To determine the chin symmetry, a vertical line is drawn passing through the midglabella, the tip of the nose (as long as the nose is straight) and the philtral dimple. The midpoint of a symmetrically located chin will fall on this line (Fig. 13.9).8 If chin asymmetry is identified, its cause should be elucidated as it impacts procedure choice. To decide whether the chin asymmetry is related to maxillary/mandibular disharmony or is intrinsic to the chin itself, the horizontal planes of the mouth and the eyes are examined. The intercommissural line should be parallel to the intercanthal line. Otherwise, vertical asymmetries of one or both of the jaws are likely to be present and genioplasty alone may not correct this condition fully. If the intercommissural line parallels the intercanthal line, a pure genial asymmetry is present and a genioplasty with osteotomy can be planned to correct the deformity (Figs 13.10 & 13.11).

Horizontal excess or deficiency is detected better in profile. There are multiple methods to determine ideal chin projection. The use of Riedel’s plane is simple and practical. With the ideal chin projection present, the most projecting portion of the upper lip, lower lip and chin are all tangent to the same line (Fig. 13.12). If the chin lies posterior to the Riedel’s plane, horizontal microgenia exists. If the chin lies anterior the plane, horizontal macrogenia exists.

An intraoral examination is mandatory in the assessment of the potential genioplasty patient. The maxillary/mandibular occlusal relationship is carefully examined. Significant periodontal disease should be identified and adequately treated prior to genioplasty to decrease the risk of infectious complications.

Life-size photography with soft tissue cephalometric analysis provides an opportunity for precise preoperative planning of augmentation or osseous genioplasty to the millimeter in both the vertical and horizontal planes.23 A circumspect facial analysis, coupled with life-size photography, can lead to an accurate definition of chin dysmorphology.

Classification of Chin Deformity

Chin pathology is classified as types I-VII according to the prevailing boney or soft tissue abnormalities.24 The type of deformity dictates which procedure should be utilized in order to attain a pleasing outcome (Table 13.1).

| Group I: Macrogenia |

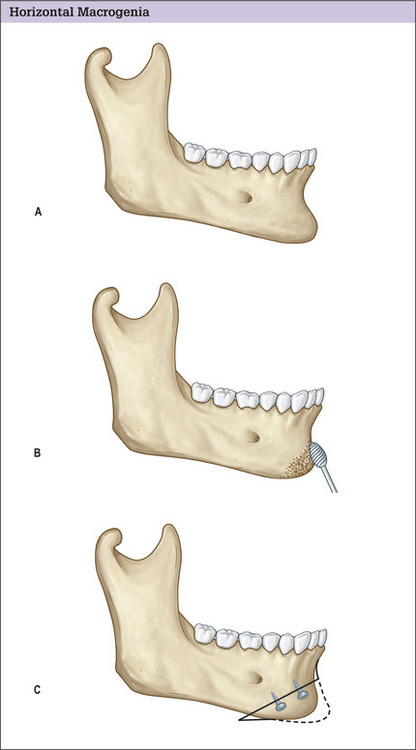

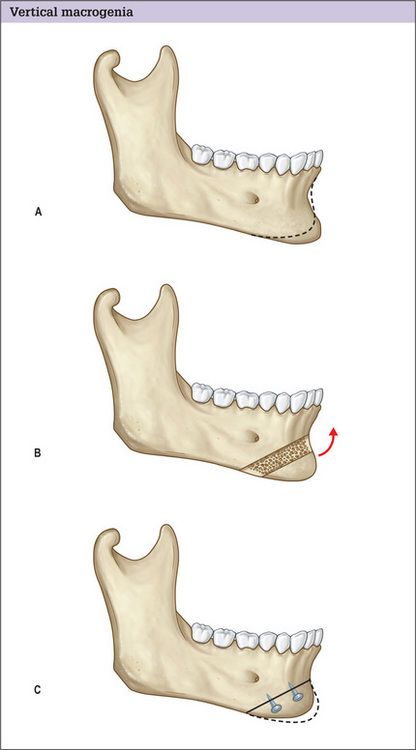

Group I deformities encompass macrogenic chins. Moderateto-severe pure horizontal macrogenia is managed by setting back the caudal segment (Fig. 13.13). Correction of pure vertical chin excess requires resection of a horizontal block or wedge segment (Fig. 13.14).

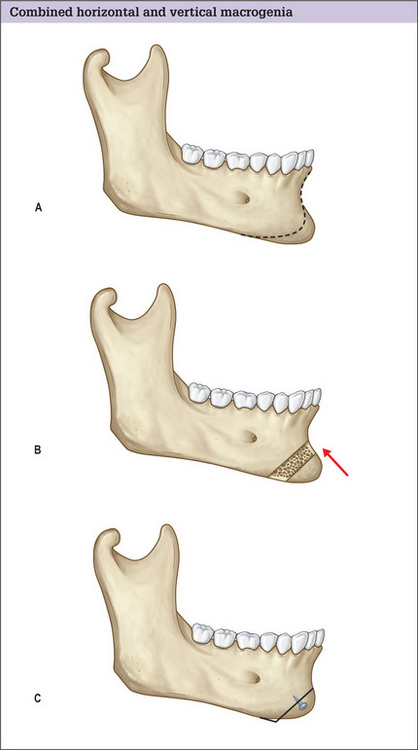

Removal of a horizontal segment with setback of the remaining caudal segment is required for combined horizontal and vertical macrogenia (Fig. 13.15).

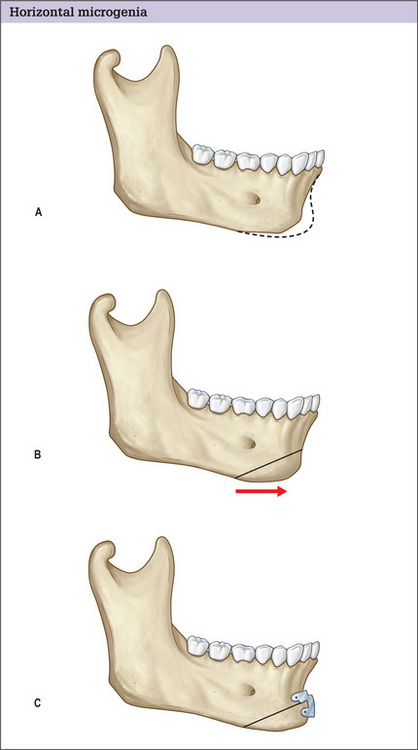

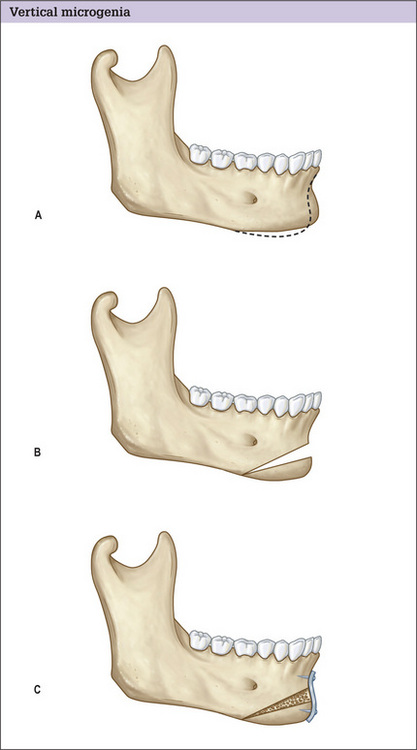

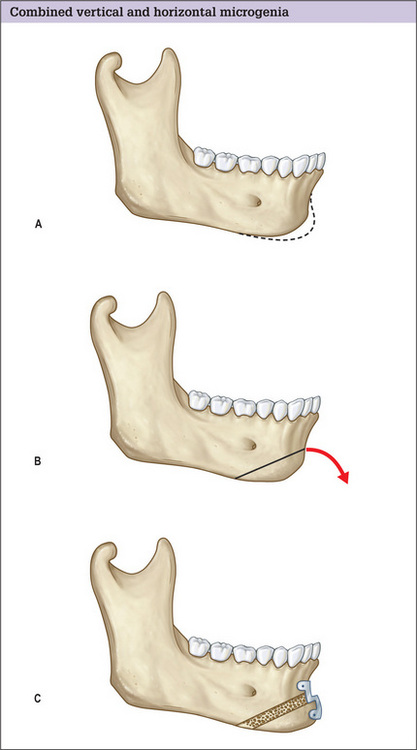

Group II deformities are comprised of microgenic chins. Augmentation genioplasty for mild or even moderate pure horizontal deficiency is discussed in a later section. A horizontal osteotomy with advancement of the caudal segment is a predictable method of treating horizontal chin deficiency (Fig. 13.16). Pure vertical chin deficiency is addressed with a horizontal osteotomy and caudal repositioning (Fig. 13.17). Combined vertical and horizontal microgenia is managed with repositioning the osteotomized chin segment caudally and anteriorly (Fig. 13.18). With any of these osteotomies, whenever caudal repositioning is performed and a gap greater than 5 mm results, interposition bone grafting or placement of a hydroxyapatite block is indicated. Smaller defects are within the osteoblastic filling (jumping) distance.

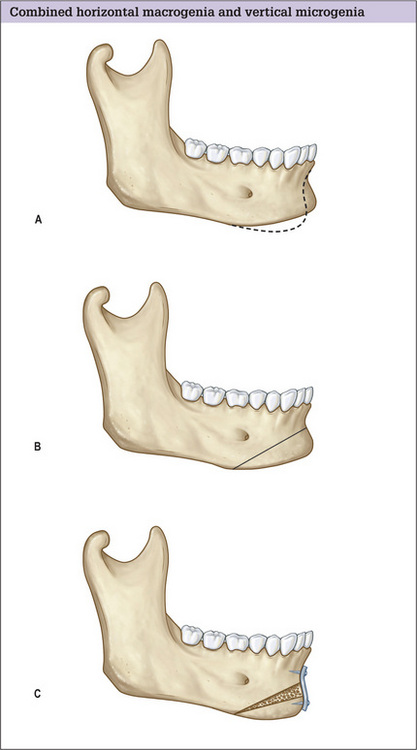

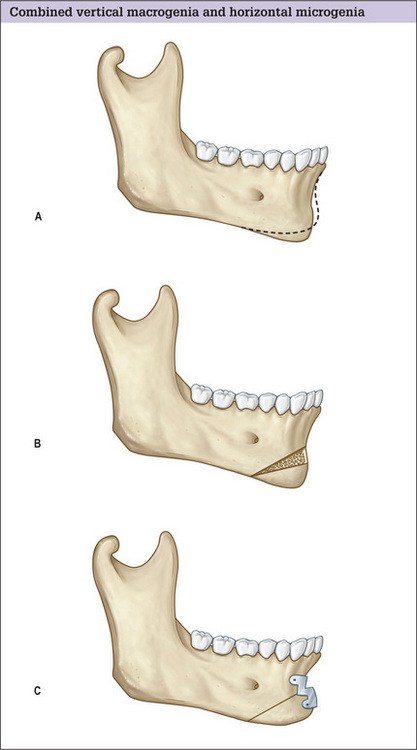

Patients with Group III chin deformities have osseous excess in one direction and deficiency in another. Combined horizontal excess with vertical deficiency is remedied with a horizontal osteotomy followed by caudal and posterior repositioning of the caudal segment (Fig. 13.19). When vertical excess is paired with horizontal deficiency, two osteotomies are performed to remove an anteriorly based wedge of bone. The caudal segment is then advanced cephalically and anteriorly and the gap is closed (Fig. 13.20).

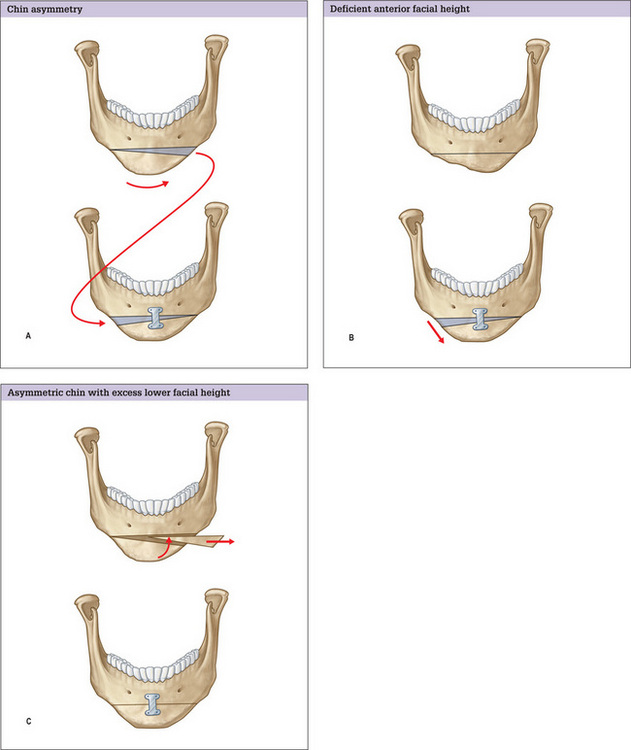

Asymmetric chins are classified as Group IV. Patients with asymmetric chins are not ideal candidates for genioplasty with alloplasts. Asymmetric chins with normal lower facial height are treated by removing a wedge from the excessive side followed by autografting of that wedge on the side of deficiency (Fig. 13.21). If lower facial height is excessive, the caudal segment is repositioned cephalically and the wedge is discarded. If the face is vertically short only one osteotomy is performed and the caudal segment is differentially moved caudally and the resultant gap is grafted with a segment of bone.25

In the correction of deformities classified as I-IV, the magnitude of caudal bone segment repositioning is determined using the knowledge of the soft tissues responses to the skeletal alterations as outlined (Table 13.2).8,26

Table 13.2 Soft tissue responses to augmentation or osseous adjustment

| Osteotomy |

| Burr osteotomy |

Group V patients have pseudomacrogenia, an excess of chin soft tissue that results in the appearance of chin excess. This diagnosis is facilitated by review of radiographic studies demonstrating excess chin soft tissue. This type of chin dysmorphology is corrected through a submental incision. Pseudomicrogenia resulting from vertical maxillary excess and clockwise rotation of the mandible constitutes the group VI chin deformity. This type of deformity requires orthognathic surgery. The group VII chin is the ‘witch’s chin’ characterized by soft tissue ptosis, which is corrected by removal of excessive soft tissues through an elliptical incision in the submental area.

Operative Approach

Osseous genioplasty

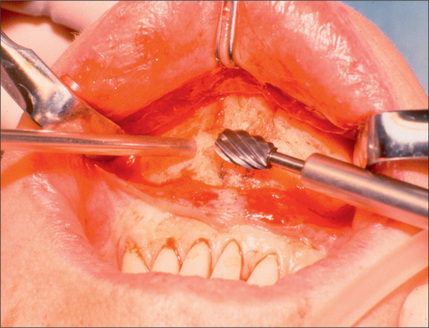

An oval burr is used to incrementally remove bone from the anterior surface of the mandible on one half at a time (Figs 13.13 & 13.22). While the burr is being used, the first-generation bone is copiously irrigated with saline containing antibiotics (1 g of cephalosporins in 1 l saline) to avoid thermal damage. More bone is removed centrally and the ostectomy is tapered laterally and superiorly to the level of the mental foramen to prevent irregularities. A caliper is used to assess the amount of bone removed on the first half to have a precise account of how much bone is removed. If the bone is removed on both sides in continuum, it will be difficult to gauge the amount of removed bone precisely. After a sufficient amount of bone is removed on one side, the procedure is repeated on the opposite side.

Following visual and digital confirmation of smooth contours, the wound is irrigated with antibiotic containing solution. It is important to close the wound in such a way that the mentalis muscle is repaired at the level it was divided and the mucosa is well approximated using 4-0 chromic sutures. A compressive tape dressing or chin sling is placed.

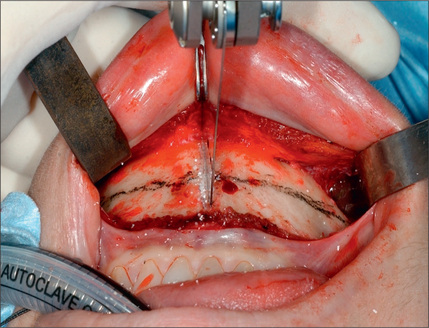

Osteotomy with caudal segment repositioning

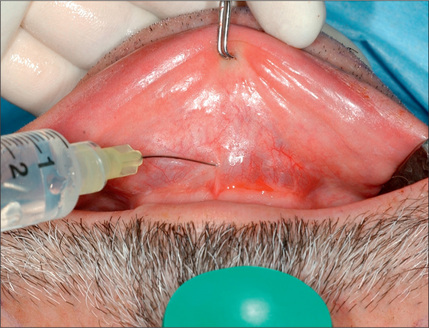

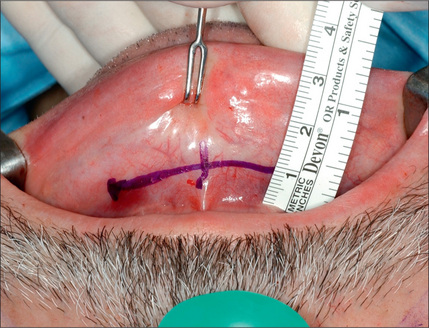

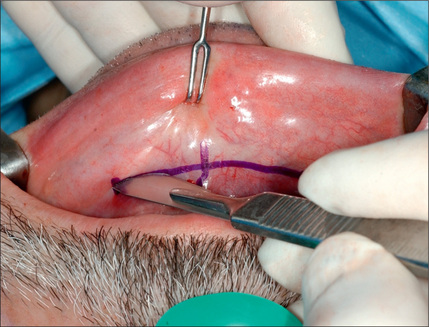

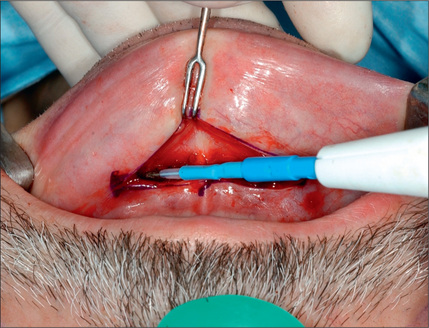

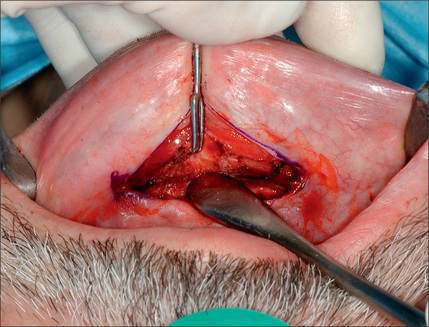

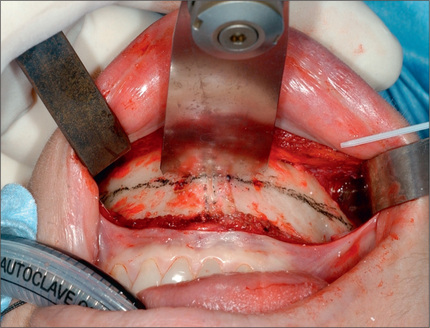

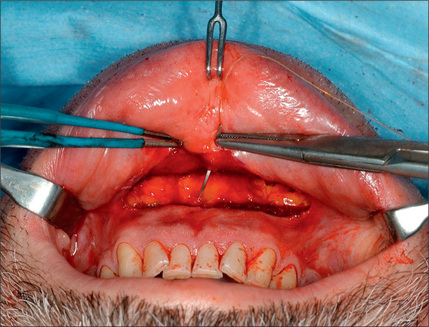

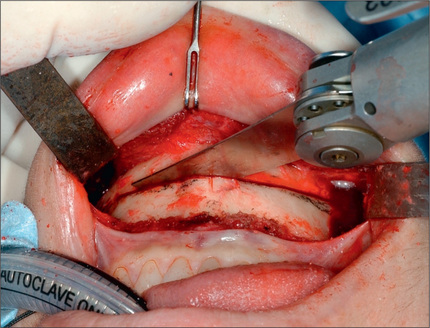

While under general or monitored anesthesia care, local blocks with 1% xylocaine containing 1 : 100 000 epinephrine are employed at the mental foramen and soft tissues over the lingual and labial surface of the mandibular symphysis are injected generously to decrease bleeding and postoperative pain (Figs 13.23 & 13.24). Exposure is achieved using the previously described intraoral approach (Figs 13.25–13.28). The inferior soft tissues are left intact to provide the blood supply to the caudal chin segment. Prior to performing an osteotomy, the midline is marked by etching a vertical line in the anterior cortical surface with a saw (Fig. 13.29).

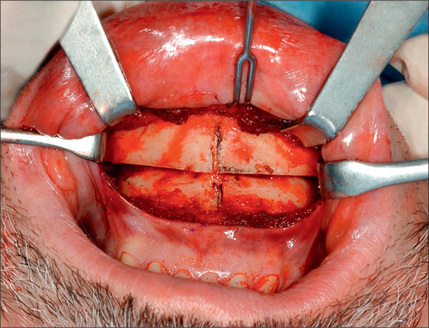

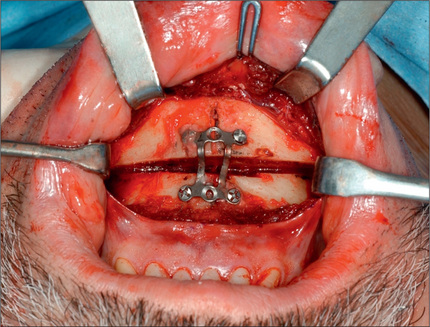

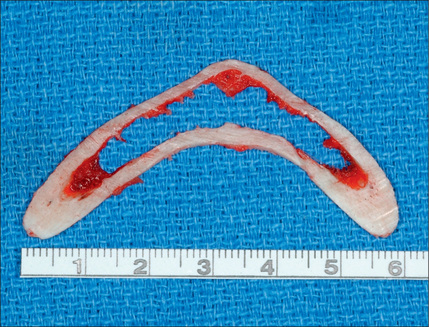

A wide saw blade isused to initiate the osteotomy in the central portion of the chin (Fig. 13.30). The saw blade is changed to a narrower one to complete the osteotomies laterally (Fig. 13.31). The osteotomy site is continuously irrigated during the course of the osteotomy. Malleable retractors protect the nerves and the other soft tissues throughout the osteotomy. After the caudal segment is freed it is advanced or retracted to the desired position (Fig. 13.32). A prefabricated step plate is contoured and placed in position to fit the anterior symphysial surface on both sides of the osteotomy (Fig. 13.33). Four screws, two on each side of the osteotomy, are placed (Fig. 13.34). Two osteotomies with removal of an intervening segment are used when a reduction in height is desired (Fig. 13.35). If setback is performed two screws should be sufficient for fixation after which a burr is used to the contour the lateral chin-mandible junctions bilaterally. The wound is then repaired as previously described (Fig. 13.36).

Fig. 13.31 The saw blade is changed to a narrower one to complete the lateral components of the osteotomy.

Fig. 13.33 The fixation plates have a step conformation to match the new contour of the anterior bone surface.

Genioplasty using augmentation techniques

In current parlance, augmentation genioplasty usually refers to the implantation of alloplastic implants. Autogenous augmentation using bone or cartilage grafts is highly successful. However, unless the graft material is readily available because of a concomitant procedure being performed, one has to forego autogenous augmentation in favor of an osteotomy, which is often simpler. In extreme craniofacial cases, however, where the chin bone deficiency is too severe to reach the intended goals with an osteotomy, one may use bone or cartilage graft.

The two most common alloplastic materials used in augmentation genioplasty are silicone and porous polyethylene. While some literature suggests that silicone implants should be placed supraperiostially to diminish bone resorption, the senior author holds that a subperosteal plane should be considered for all implant types. Placing the implant in this plane and over the symphysis would minimize the soft tissue injury, dimpling and migration of the implant. Bone erosion will be also minimized if the implant is placed over the denser portion of the bone. Furthermore, if contracture should occur, the deeper location of the implant limits the deleterious affects on the soft tissue contour. The soft tissue response to augmentation genioplasty is 0.8 : 1.0 (Table 13.2).

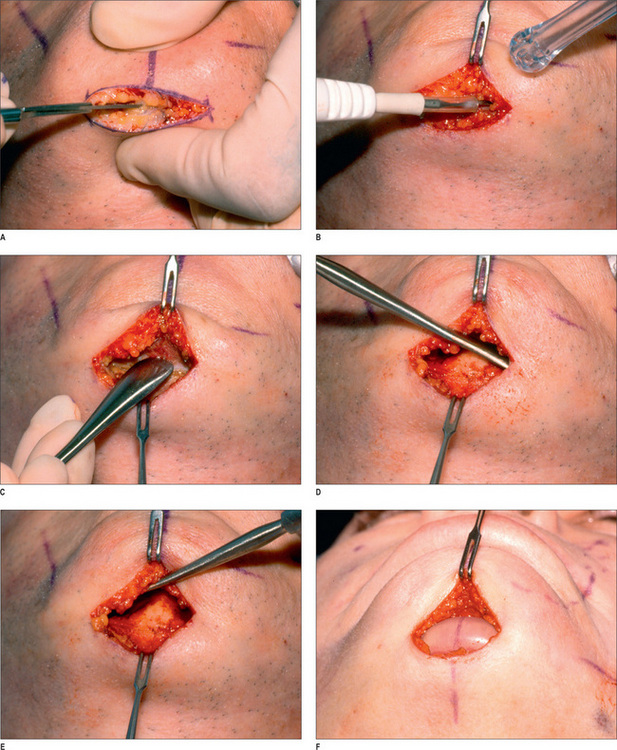

The submental incision is placed 0.5 cm anterior to the natural submental crease. Prior to making an incision, the midline of the anterior chin is marked and extended across the incision. The area is infiltrated with xylocaine containing 1 : 200 000 epinephrine. The incision is made with a scalpel and carried through the soft tissues with electrocautery to the periosteum. The periosteum is incised and elevated. The midline mark on the skin is used to mark the underlying bone. A symmetric pocket is created just large enough to accommodate the implant using an Obwegeser elevator. The implant is inserted one side at a time and is positioned such that its midline is aligned with the midline of the chin as marked previously (Fig. 13.37). The wound is irrigated and the periosteum is closed using 5-0 monocryl for the periosteum and dermis and 6-0 fast-absorbable catgut for the skin. The soft tissue and skin are closed in layers. A tape dressing is applied. The patient will receive antibiotics perioperatively. An intraoral incision is employed when extended implants or mandibular angle implants are used. These are placed in the subperiosteal plane as well.

Optimizing outcomes

Outcomes are generally pleasing and improve chin appearance and overall facial harmony (Figs 13.38–13.41). Outcomes can be optimized as follows:

Complications and Side Effects

Complications are rare. Nevertheless, the surgeon must understand their potential causes and management (Table 13.3).27

Table 13.3 Complications of genioplasty and their management

| Complication Management | Management |

|---|---|

| Osteotomy | |

| Dehiscence and infection | Irrigation, debridement and closure of wound if hardware is stable, systemic antibiotics |

| Hematoma | Drainage |

| Tooth devitalization | Root canal by a dentist |

| Dental root exposure | Gingival grafting |

| Neurosensory loss | Conservative/expectant initially; neurorraphy if anesthesia persists |

| Soft tissue ptosis | Submental incision with skin excision |

| Asymmetry | Early re-operation prior to osseous healing |

| Overcorrection/undercorrection | Early re-operation prior to osseous healing |

| Irregularities and step-type deformities | Observe 6 months. If no improvement is noted recontour with oval burr |

| Lower lip retraction | Lip advancement |

| Augmentation | |

| Dehiscence/extrusion | Removal of implant, irrigation, closure, use of antibiotics |

| Infection | Explantation, irrigation, antibiotics and delayed osteoplastic genioplasty |

| Malposition | Re-operation with re-positioning |

| Bone resorption | Explantation and osteoplastic genioplasty if the impant is endangering the tooth root |

| Capsular contracture | Explantation and osteoplastic genioplasty |

| Lower lip retraction | Repair of mentalis muscle, lip advancement |

Complications of osseous genioplasty

Wound dehiscence and infection

Wound dehiscence and infection are rare after osseous genioplasty. As long as there is no loose or exposed hardware, most wound dehiscences will close spontaneously. Conservative debridement and irrigation, and intravenous followed by oral antibiotics are indicated. In most incidences, this regimen protects the osteotomy site and may avoid removal of the screws and plates.

Neurosensory loss

Some degree of lip paresthesia occurs in more than one half of the patients treated with osteotomy of the chin bone. Sensory loss or reduction is often a temporary condition in almost all patients.28 When numbness persists, it is generally characterized as hyposthesia, not anesthesia. When traction is the etiology, sensation generally returns within days to weeks. However, avulsion or transection injury during an osteotomy can occur if the osteotomy is too close to the mental foramen due to the fact that the nerve has a brief caudal course prior to emerging from the mental foramen (Fig. 13.6). Complete sensory loss with no recovery after 1 year may require exploration and neurorraphy.

Lower lip retraction

Lower lip retraction is a manifestation of a loss of lower lip support. It results in descent of the lower lip position and an increase in lower incisor show. This complication is generally the consequence of incomplete or improper mentalis muscle repair.29,30 This deformity can be corrected through an intra-oral incision, extensive subperiosteal dissection and suspension of the periosteum cephalically.

Complications of augmentation genioplasty

Extrusion

Extrusion presents in a similar fashion as dehiscence, although dehiscence does not necessarily always expose the implant. When a chin implant is exposed, it is removed, the wound is irrigated and the wound edges are loosely approximated, and oral antibiotics are prescribed for 5-7 days. The residual or resultant deformity is best managed by osteoplastic genioplasty.

Bone resorption

Almost all augmentation genioplasties will result in some degree of bone resorption under the implant.31,32 This complication is more common with non-porous implants such as silicone or acrylic. As resorption is essentially inevitable, care must be taken to place the implant caudally enough so that when bone erosion occurs, dental roots are not placed in peril. Additionally, the magnitude of resorption is less caudally due the higher bone density and decreased activity of the muscle overlying the implant. In case of pending erosion of the tooth roots, the implant should be removed and an osteotomy should be performed.

Capsular contracture

Capsule contracture is almost exclusively seen when a smooth implant is utilized, in particular silicone implants. This type of contracture distorts the implant and generates an unnatural soft tissue contours punctuated by a central bulge. Explantation, removal of the capsule anteriorly, and osseous genioplasty are indicated; however, these interventions are not universally successful due to residual soft tissue distortion.

Lower lip retraction

Lip retraction presents with less frequency when submental access is used compared to the intra-oral incision. When it occurs, surgical elevation of the soft tissues with a subperiosteal dissection and cephalic fixation with bone tunneling or anchor suture may prove successful.33

Postoperative Care

The patient resumes eating the day of surgery. Liquids are advanced to a soft diet and then a regular diet according to the patient’s general tolerance of food within 24-48 hours. The patient is instructed to rinse with antiseptic mouthwash after eating and three times daily. Tooth brushing can be resumed the day of surgery, but the patient should be instructed to exercise caution when cleaning the area close to the incision. Oral antibiotics are prescribed for 5-7 days. The patient should avoid heavy exercise for 3 weeks following osteotomy. Foam type compressive tape dressing is removed in 2-3 days (Table 13.4).

| Short term |

Conclusion

1. Guyuron B. Genioplasty. In: Ferraro J.W., editor. Fundamentals of maxillofacial surgery. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag New York Inc, 1997.

2. Cohen S., Mardach O., Kawamoto H.K.Jr. Chin disfigurement following removal of alloplastic chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88(1):62-66. discussion 67-70

3. Li K., Cheney M. The use of sliding genioplasty for treatment of failed chin implants. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(3 Pt 1):363-366.

4. Peck H., Peck S. A concept of facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 1970;40(4):284-318.

5. Rosen H. Aesthetic guidelines in genioplasty: the role of facial disproportion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(3):463-469. discussion 470-472

6. Gonzalez-Ulloa M. Quantitative principles in cosmetic surgery of the face (profileplasty). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1962;29:186-198.

7. Danahey D., Dayan S., Benson A., Ness J. Importance of chin evaluation and treatment to optimizing neck rejuvenation surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2001;17(2):91-97.

8. Guyruon B. Genioplasty. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1993.

9. Zide B., Pfeifer T., Longaker M. Chin surgery: I. Augmentation – the allures and the alerts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(6):1843-1853. discussion 1861-1862

10. Spear S., Kassan M. Genioplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16(4):695-706.

11. Frodel J., Sykes J., Jones J. Evaluation and treatment of vertical microgenia. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(2):111-119.

12. Hinds E., Kent J. Genioplasty: the versatility of horizontal osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1969;27(9):690-700.

13. Hohl T., Epker B. Macrogenia: a study of treatment results, with surgical recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41(5):545-567.

14. Park H., Ellis E.3rd, Fonseca R., Reynolds S., Mayo K. A retrospective study of advancement genioplasty. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67(5):481-489.

15. Wessberg G., Wolford L., Epker B. Interpositional genioplasty for the short face syndrome. J Oral Surg. 1980;38(8):584-590.

16. Millard D.R.Jr. Chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1954;13(1):70-74.

17. Wolfe S., Rivas-Torres M., Marshall D. The genioplasty and beyond: an end-game strategy for the multiply operated chin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(5):1435-1446.

18. Guyuron B., Raszewski R. A critical comparison of osteoplastic and alloplastic augmentation genioplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;14(3):199-206.

19. Hwang K., Lee W., Song Y., Chung I. Vulnerability of the inferior alveolar nerve and mental nerve during genioplasty: an anatomic study. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(1):10-14. discussion 14

20. Ousterhout D. Sliding genioplasty, avoiding mental nerve injuries. J Craniofac Surg. 1996;7(4):297-298.

21. Ritter E., Moelleken B., Mathes S., Ousterhout D. The course of the inferior alveolar neurovascular canal in relation to sliding genioplasty. J Craniofac Surg. 1992;3(1):20-24.

22. Guyuron B., Raszewski R. Undetected diabetes and the plastic surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86(3):471-474.

23. Guyuron B. Precision rhinoplasty. Part I: the role of life-size photographs and soft-tissue cephalometric analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81(4):489-499.

24. Guyuron B., Michelow B., Willis L. Practical classification of chin deformities. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995;19(3):257-264.

25. Guyuron B. The use of rigid fixation in the treatment of facial asymmetries. In: Yaremchuk M.J., Gruss J.S., Manson P.N., editors. Rigid fixation of the craniofacial skeleton. Stoneham, MA: Butterworth Publishers, 1992.

26. Michelow B., Guyuron B. The chin: skeletal and soft-tissue components. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(3):473-478.

27. Guyuron B., Kadi J. Problems following genioplasty. Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24(3):507-514.

28. Lindquist C., Obeid G. Complications of genioplasty done alone or in combination with sagittal split-ramus osteotomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66(1):13-16.

29. Zide B. The mentalis muscle: an essential component of chin and lower lip position. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(3):1213-1215.

30. Chaushu G., Blinder D., Taicher S., Chaushu S. The effect of precise reattachment of the mentalis muscle on the soft tissue response to genioplasty. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(5):510-516. discussion 517

31. Friedland J., Coccaro P., Converse J. Retrospective cephalometric analysis of mandibular bone absorption under silicone rubber chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57(2):144-151.

32. Matarasso A., Elias A., Elias R. Labial incompetence: a marker for progressive bone resorption in silastic chin augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(6):1007-1014. discussion 1015

33. Zide B., Boutros S. Chin surgery III: revelations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(4):1542-1550. discussion 1551-1552