Chapter 48 Genioglossus advancement in sleep apnea surgery

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is associated with airway obstruction due to a decrease in upper airway muscle tone during sleep. Because the genioglossus muscle is a major pharyngeal dilator, it has long been suggested to play a major role in nocturnal airway obstruction. Genioglossus advancement is a surgical procedure which places the genioglossus muscle under tension, thus restricting the collapse of the tongue into the airway during sleep-induced hypotonia. This chapter describes my technique.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hypopharyngeal obstruction is a major contributing factor in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Hypopharyngeal obstruction stems from the prominence or relaxation of the base of the tongue, lateral pharyngeal wall collapse, and occasionally involves the aryepiglottic folds or epiglottis.1–3 Because the genioglossus muscle is a major pharyngeal dilator, it has long been suggested to play a major role in nocturnal airway obstruction.4,5 Genioglossus advancement is a surgical procedure designed to place the genioglossus muscle under tension, thus restricting the collapse of the tongue into the airway during sleep-induced hypotonia. Multiple studies have demonstrated that genioglossus advancement combined with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty achieves improvement of OSA.6–8 Several designs of the osteotomy during genioglossus advancement have been described, with each one aimed at minimizing the surgical morbidity while improving the incorporation and the advancement of the genioglossus muscle.6,9–11

3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

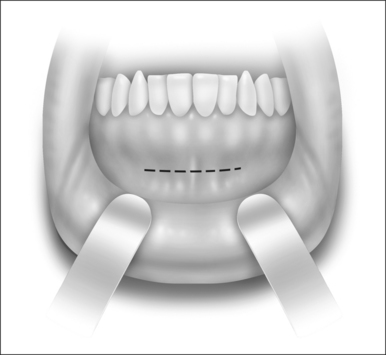

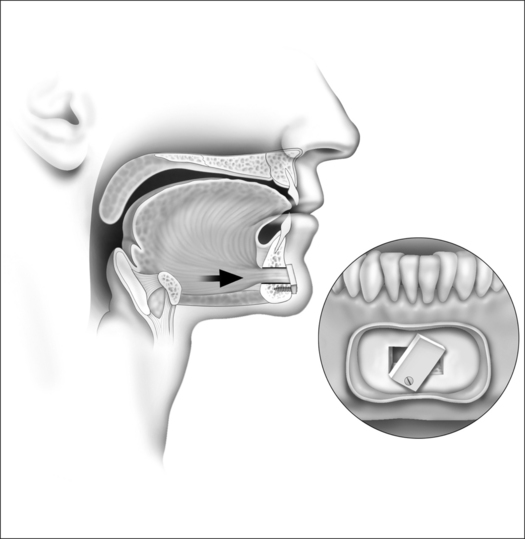

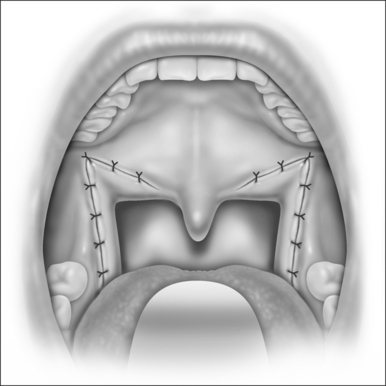

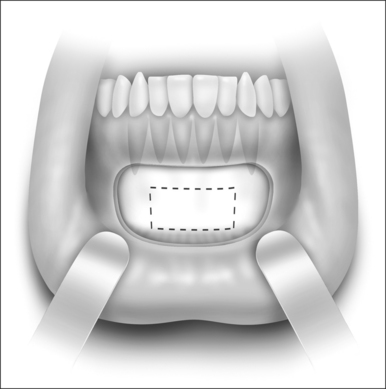

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with oroendotracheal intubation. Local anesthetic injection (10 milliliters of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine) is administered at the anterior mandibular vestibule. The procedure begins with a mucosal incision approximately 10 mm below the mucogingival junction (Fig. 48.1). A subperiosteal dissection is performed to expose the mandibular symphysis. Exposure and identification of the mental nerves are unnecessary as the mental foramen is lateral to the surgical site. The genial tubercle and genioglossus muscle can be estimated by finger palpation in the floor of the mouth and with the aid of the lateral cephalometric and panoramic radiographs. A rectangular osteotomy encompassing the estimated location of the genial tubercle is performed under copious irrigation (Fig. 48.2). It is recommended that the superior horizontal bone cut be at least 5 mm below the mandibular root apices to decrease the likelihood of tooth paresthesia. The inferior horizontal bone cut should be designed to preserve approximately 10 mm of the inferior border of the mandible to reduce the risk of a pathologic mandibular fracture. If there is insufficient mandibular symphyseal height, this procedure should not be performed as the risk of pathologic mandibular fracture or tooth root injury is increased. Due to the elongated canine tooth roots that are often present, the vertical bone cuts are made just medial to the canine tooth to avoid root injury. It is crucial to follow parallelism of the osteotomies to facilitate the ease of releasing the rectangular bone flap. Prior to completing the osteotomy, a titanium screw is placed in the outer cortex to control and manipulate the bone flap. At the completion of the osteotomy, the bone flap is released from the surrounding bone and is advanced and rotated 60° to prevent retraction back into the floor of the mouth. The outer cortex and marrow are removed and the inner cortex is rigidly fixed with a lag screw (Fig. 48.3).

Fig. 48.2 A rectangular osteotomy encompassing the estimated location of the genial tubercle is performed.

4 DISCUSSION

It is well recognized that the hypopharyngeal airway often needs to be addressed in order to maximize the surgical response in sleep apnea treatment. Genioglossus advancement has been utilized in the management of hypopharyngeal obstruction since the 1980s.12 Regardless of the osteotomy design, the principle of the procedure is the same, i.e. advancing of the genioglossus muscle and limiting the tongue base collapse. It should be pointed out that there are advantages and disadvantages with different designs. The rectangular osteotomy described in this article is less invasive when compared to the mortise osteotomy which includes the lower border. It also minimizes the risk of mandibular fracture since the lower border of the mandible is preserved. The genioglossus muscle is routinely captured in the advancement. However, the rectangular design is more technically challenging. Although the mortise design captures more muscle in the advancement, the advancement is usually less. Regardless of the osteotomy design, potential complications of genioglossus advancement include bleeding, infection, paresthesia, anesthesia or dysthesia of the chin and teeth as well as mandibular fracture.

Although most studies have shown that combining uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and genioglossus advancement achieves improvement of OSA, the success rate can be quite variable, ranging from 22% to 67%.6–13 This is likely due to the complexity associated with the etiology of OSA, patient selection and surgical execution.

1. Rojewski T.E., Schuller D.E., Clark R.W., et al. Videoendoscopic determination of the mechanism of obstruction in obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:127-131.

2. Kletzker G.R., Bastian R.W. Acquired airway obstruction from histologically normal abnormally mobile supraglottic soft tissues. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:375-379.

3. Schwab R.J., Gefter W.B., Hoffman E.A. Dynamic upper airway imaging during awake respiration in normal subjects and patients with sleep disordered breathing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1385-1400.

4. Remmers J.E., Degroot W.J., Sauerland E.K., Anch A.M. Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44:931-938.

5. Mezzanotte W.S., Tangel D.J., White D.P. Waking genioglossal electromyogram in sleep apnea patients versus normal controls (a neuromuscular compensatory mechanism). J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1571-1579.

6. Miller F.R., Watson D., Boseley M. The role of the genial bone advancement trephine system in conjunction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in the multilevel management of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:73-79.

7. Lee N.R., Givens C.D.Jr., Wilson J., Robins R.B. Staged surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 35 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:382-385.

8. Kezirian E.J., Goldberg A.N. Hypopharyngeal surgery in obstructive sleep apnea: an evidence-based medicine review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:206-213.

9. Li K.K., Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Troell R.J. Obstructive sleep apnea surgery: genioglossus advancement revisited. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1181-1184.

10. Li K.K. Discussion on A protocol for UPPP, mortised genioplasty, and maxillomandibular advancement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an analysis of 40 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:898-899.

11. Hendler B., Silverstein K., Giannakopoulos H., Costello B.J. Mortised genioplasty in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: an historical perspective and modifications of design. Sleep Breath. 2001;5:173-180.

12. Riley R., Guilleminault C., Powell N., Derman S. Mandibular osteotomy and hyoid bone advancement for obstructive sleep apnea: a case report. Sleep. 1984;7:79-82.

13. Bettega G., Pepin J.L., Veale D., Deschaux C., Raphael B., Levy P. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Fifty-one consecutive patients treated by maxillofacial surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:641-649.