Chapter contents

8.1 Same disease different pulse; different pulse same disease 179

8.2 External pathogenic attack versus internal dysfunction 179

8.3 Blood 188

8.4 Qi 196

8.5 Yin vacuity 198

8.6 Yang vacuity 198

8.7 Health 199

8.8 The Unusual or Death pulses 200

8.1. Same disease different pulse; different pulse same disease

A clinical complication for the use of pulse diagnosis is that there can be a range of quite distinctly different pulse qualities that form in response to apparently the same illness or dysfunction. Blood vacuity or anaemia is an apt example of this. Blood vacuity pulses can present with both increased and decreased changes in the arterial width. With this in mind, there is still a further complication with the similarity of some pulses; while they are similar, diagnostically they reflect different pathological processes and the general health of the patient. This situation is aptly described in the Chinese medical axiom:

Tong bing yi zhi,

Yi bing tong zhi,

Different disease, one treatment

Same disease, different treatments

8.2. External pathogenic attack versus internal dysfunction

External pathogenic attack (EPA) refers to pathogenic agents external to the body that give rise to illness and can cause dysfunction. From a biomedical perspective this can broadly relate to common colds and influenzas and encompass other viral, fungal and bacterial agents. In a CM context, categorisation of illness due to pathogenic agents is based on the resultant signs and symptoms, the body’s response to the pathogenic agent. In this sense, pathogenic agents causing fever are broadly classified as Heat; pathogenic agents causing swelling and oedema are classified as Damp. There are also Cold, Dry and Wind pathogenic agents in addition to Heat and Damp. Pathogenic agents can also combine to form complex conditions such as Damp Heat as seen in viral infections such as varicella (chickenpox).

A traditional assumption associated with the pulse when EPA attacks the body is the movement of the body’s defensive Qi to accumulate or move outwards to the superficial regions of the body. The pulse correspondingly becomes relatively stronger at the superficial levels of depth. EPAs are a perverse version of Qi, certainly pathogenic, but still Qi. In this sense, when a pathogen attacks the body then there is extra Qi, additional to the normal levels of Qi in the body. The addition of the Qi makes the overall force of the pulse increase. This occurs in addition to the increasing defensive Qi levels at the external parts of the body to counter the EPA and reflected in the pulse as being strongest at the superficial level of depth.

When the pulse is distinctly stronger at the superficial level of depth, and consecutively less strong at the middle and deep levels of depth, then this is termed a Floating pulse reflecting the movement of defensive Qi to counter the pathogen.

The Floating pulse also occurs with internal dysfunction causing conditions of hyperactivity such as seen in states of anxiety or stress. This is termed Yin vacuity (Yin deficiency). This occurs when the body’s ability to control Yang is compromised, causing increased activity of Yang. The Floating pulse occurs as Yang moves upwards and outwards, which is seen as pulling the Qi and blood with it. Another useful way of looking at this is via the control mechanisms of the autonomic nervous system; the parasympathetic nervous system’s counter control to the sympathetic nervous system, and the related feedback systems are no longer able to keep activity in check.

The Floating pulse can therefore occur in the presence of EPA but also with internal dysfunction. As there are two quite distinct aetiologies, the Floating pulse can be further differentiated by the related changes in other accompanying pulse parameters. In this case the Floating pulse due to an EPA is accompanied by an increase in pulse force, reflecting the increased metabolic demands of the body to combat the pathogen. The Floating pulse resulting from Yin vacuity will have a decrease in pulse force reflecting the empty-type hyperactivity occurring.

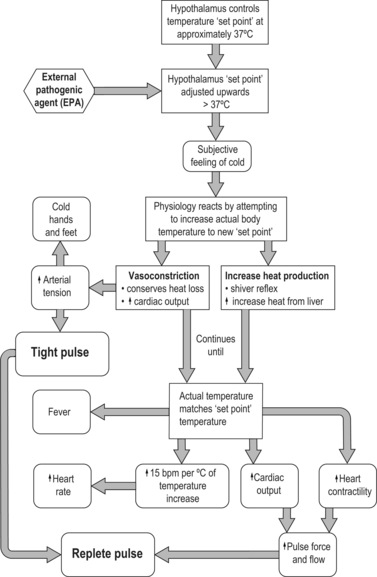

There are a range of pulse qualities that occur with external attack by pathogenic agents. Although most of these pulse qualities are strongest at the superficial level of depth, they will by no means all present as a Floating pulse. Depending on the changes in other pulse parameters, usually in regard to the type of pathogenic agent, several other traditional pulse qualities can develop. There are specific differences in the parameters of these pulses that differentiate them from the Floating pulse, as there are specific differences in the parameters of the Floating pulse to further differentiate it from other superficially occurring pulses. Additionally, not all acute pathogenic attacks will result in a superficially strong pulse, because sometimes the pathogen goes directly into the interior and affects organ function. The pathogen can also mutate, so one pulse quality occurs initially and as the pathogen mutates so the pulse quality also changes. The Tight pulse in response to Cold EPA moving to the Replete pulse occurs as the Cold EPA becomes warmed by the body’s heat. (Fig. 8.1)

|

| Figure 8.1The likely transformation of an EPA of Cold to Heat and the formation of the Tight pulse and consequent formation of the Replete pulse. (Developed from information in Dinarello & Gelfand 2001). |

Following is a discussion on the pulses formed with different pathogenic agents. Additionally, some of these pulse qualities can also occur via mechanisms reflecting internal dysfunction of the body’s homeostasis or balance and are not necessarily due to an EPA; the discussion focuses on these differences and hence appropriate classification methods.

8.2.1. Pulse qualities reflecting Damp

The term ‘damp’ is used both descriptively and diagnostically. Descriptively it is used to describe any accumulation of fluids or moisture. This can be apparent as with the retention of fluid clearly seen with swelling of the ankles or face, overproduction of mucous, runny nose or coughing mucous from the lungs (Box 8.1). When the term ‘damp’ is applied diagnostically, it is used to describe the pathogenesis or cause of the illness as arising from Damp. In this sense, it is used to describe the symptomatic manifestation of Damp signs and symptoms. The term also loosely encompasses phlegm, which occurs when fluids congeal.

Box 8.1

Damp signs and symptoms

• Feelings of heaviness/fullness

• Lethargy

• Nausea/bloating

• Oedmea/fluid retention

• Copious urination

• Readily combines with pathogens of Cold and Heat

Damp illness can arise from internal and external causes. As an internal cause, Spleen Yang Qi vacuity or digestive weakness often gives rise to Damp accumulation as the distribution and transformation function of moving fluids and nutrients around the body is compromised and so fluid accumulates producing Damp. Diet-related causes are also common when particular food groups causing Damp are eaten in excess or are unable to be appropriately digested. For example, dairy products, raw foods, cold foods, oils and uncooked foods can be causes of Damp accumulation, often affecting the Spleen Qi and/or Yang. Damp formation also arises from external causes. For example, external pathogenic agents such as Cold have a congealing affect on the fluid in the body producing dampness, or Damp can arise from Damp pathogenic agents as well.

From a pulse diagnosis perspective, four of the traditional pulse types are associated with Damp:

• Slippery pulse (section 7.9.1)

• Soggy pulse (section 7.7.6)

• Moderate pulse (section 6.4.3)

• Fine pulse (section 6.12.1).

One other pulse quality can be categorised with Damp, and is associated with the formation of phlegm in particular:

• Stringlike (Wiry) pulse (section 7.5.1).

The first four pulses associated with Damp can be divided into two categories based on the parameters of their formation. The first grouping is that of Fine pulse and Soggy pulse, similar in width. The second grouping is the Moderate pulse and Slippery pulse, similar in contour. The two groupings are quite distinctly different. The first is a change in the physical characteristic of the artery, that of width, while for the second grouping it is a noticeable change in the pulse wave contour. Each is discussed in further detail below.

8.2.1.1. Fine pulse and Soggy pulse

The Fine and Soggy pulses are similar in their presentation, presenting with a reduction in arterial width and are forceless. In fact, as the Fine pulse is often used as a general descriptor of all superficial narrow pulses, the Soggy pulse and Fine pulse, in this instance, are one and the same for the presentation of damp. The Soggy pulse is a narrow pulse, an extension of the Fine pulse, because it has changes in other parameters which the Fine pulse does not.

The pathogenesis of the formation of these pulses arises from damp due to internal vacuity, or where damp has caused internal vacuity of Yang.

The Soggy pulse generally reflects vacuity of Qi and Yin/Blood but also presents with a further decreased force when damp is present. In this situation there is no distinct change in the contour of the pulse wave, as seen with the Slippery pulse and Moderate pulse. The forceless nature of the pulse which occurs in the Soggy pulse arises from the damp impairing the ability of the pulse wave or Yang to expand. Damp pathogenesis from an EPA is additionally reflected in the presentation of the Soggy pulse, felt strongest at the superficial level of depth where the body’s defensive Qi rises to fight the pathogen.

8.2.1.2. Slippery pulse and Moderate pulse

The Slippery and Moderate pulses are very similar in their presentation, both presenting with distinct contour changes in the accompanying pulse wave. They are differentiated by the parameter of pulse rate and also by the strength and speed of cardiac contraction. The Slippery pulse is described as occurring in the presence of heat and so the pulse rate is likely raised. There would additionally be an increase in the strength and speed of cardiac contraction so the pulse is also felt strong and distinct. The Moderate pulse has a pulse rate of 60 bpm – reflecting a relative cold pathogen. As such, both pulse qualities can represent damp but are differentiated by the nature of the damp, whether hot or cold. There are probably additional differences in the underlying mechanisms of pathogenesis which further differentiate the two pulses. For the Moderate pulse, the damp is seen as having a constraining affect on the body’s activity (Yang). This suggests that the constitutional strength of the individual has a distinctive role in whether the Slippery or Moderate pulse will occur. (The difference between the Moderate pulse and Soggy pulse in this instance is that there is sufficient arterial volume with the Moderate pulse, while with the Soggy pulse, blood is vacuous or of not good quality.)

The contour changes associated with the Slippery and Moderate pulses can be explained by the appropriate physiological strength of the Qi and blood, in spite of the presence of a pathogenic agent. The pulse can then be seen to represent relatively new illness. (For the Soggy pulse the Qi and blood have been affected or were already depleted when the Damp pathogen arose.)

When Qi and blood are abundant, and there are no apparent signs of illness, then a similar pulse presentation of the Slippery pulse and Moderate pulse can occur as a sign of health. In this instance, the Slippery pulse is differentiated from the Moderate pulse by the parameter of pulse rate. The Moderate pulse has a pulse rate of 60 bpm.

Possible parameter changes associated with Damp (Table 8.1)

• Arterial width narrows: The Soggy pulse and Fine pulse form because blood is already depleted so Damp compresses the pulse.

• Pulse contour and flow wave changes: The Moderate pulse and Slippery pulse form only when blood is abundant or arterial volume is full (whether from blood or fluid accumulation).

8.2.1.3. Stringlike (Wiry) pulse (Xián mài)

The Stringlike (Wiry) pulse can reflect the consequences of a particular form of damp termed phlegm. Phlegm occurs as a result of congealed fluids due to pathogenic factors such as heat or fire, or from the poor circulation of fluids causing these to collect and congeal. The Spleen and Lungs are often linked to internal causes of phlegm formation because of their functional relationship with circulating and transforming fluids.

Phlegm is an obstructive substance impeding the normal flow of Qi and blood through the tissue and organs, placing stress on the system. Phlegm causes obstructions, obstructions cause pain. An increase in arterial tension is therefore not an unexpected response. (Note that phlegm is divided into further complex patterns dependent on other signs and symptoms. Relevant texts should be consulted for further information.)

8.2.1.4. Clinical application of the damp pulses

Clavey (2003) notes that diagnosis of damp or phlegm conditions should not depend solely on on the pulse. He notes that a lack of a ‘damp pulse’ does not preclude the presence of damp (p. 296). The reason for this is that damp is often a symptomatic consequence of dysfunction. For example, when the body’s Yang warming function is impaired, moisture accumulates and congeals producing damp. In this situation, damp is secondary to the primary Yang vacuous condition. Lyttleton (2004) describes a scenario of infertility in a patient due to blockage of the reproductive organs due to Phlegm-Damp in which the damp pathology does not manifest on the pulse:

… if the accumulation of Phlegm-Damp is isolated in a discrete location (e.g. one fallopian tube) then it may not register on the pulse. If Kidney Yang deficiency or Liver Qi stagnation are contributing causes of the Phlegm-Damp, their characteristics may be felt on the pulse instead (p. 96).

8.2.2. Pulse qualities that reflect Cold EPA

Cold by nature contracts and obstructs, it congeals fluids and counters the warming nature of Yang. Heat produced from metabolism is an expression of the body’s Yang-related functions and so when a pathogen of Cold invades then the body’s physiological functions are affected. This can arise in signs and symptoms such as chills and aversion to cold (Box 8.2). Cold invasion affects the pulse in three ways:

• Pulse rate: Qi is seen as a motive force, giving rise to and ensuring the regularity of the heart contraction and movement of blood in the vessels. Pulse rate is a reflection of the functional activityof Yang to speed up or slow the heart rate. As Cold counters the Yang then the pulse rate slows (but importantly, heart rhythm is not interrupted as the heart Qi remains functional).

• Arterial tension: Cold has a contracting action on the flesh, and arterial tension increases as the Cold contracts the flesh. An increase in tension can also be viewed in this respect as the body’s attempt to maintain internal warmth, conserve the Yang, by reducing the area of the artery and Qi and blood exposed to the pathogenic Cold: a defensive mechanism to prevent internal invasion of Cold. Control of temperature regulation from a biomedical perspective is associated with the hypothalamus, which increases the body’s ‘normal’ temperature to a higher set point, and so the physiological response is an attempt to conserve body heat in order to raise body temperature to the new set point (see Fig. 8.1) From a CM perspective, an increase in arterial tension can also refer to the obstructive action of Cold on the normal flow of Qi and blood. Obstruction is associated with pain, and pain causes an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity further affecting arterial wall tension.

• Level of depth and strength: The level of depth at which the pulse is felt strongest with Cold pathogens is variable and depends on the body’s immune function and the intensity of the Cold pathogen. This is because acute Cold pathogens are known to affect the internal organs almost immediately, while other types follow a progressive movement from the exterior to the interior over time. In the former case the pulse is felt strongest at the deep level of depth and in the latter, at the superficial level of depth.

Box 8.2

Cold signs and symptoms

• Aversion to cold

• Chills

• Preference for warmth and warm drinks

• Clear coloured urine

• Combines with pathogens of Wind and Damp

• Pulse parameters:

– Slow rate

– Increased arterial tension

Five traditional pulse qualities are associated with Cold invasion or are attributable to the presence of a Cold EPA:

• Drumskin pulse (section 7.5.4)

• Tight pulse (section 7.5.2)

• Firm pulse (section 7.7.2)

• Hidden pulse (section 6.9.3).

Of these five traditional pulse qualities, the Slow pulse is the simplest to recognise and will nearly always be accompanied by signs and symptoms that reflect Cold. It is likely to combine with the other four pulse qualities when Cold pathogens are present. For example, the Tight pulse due to Cold will have increased arterial tension and a decrease in pulse rate.

The remaining four pulses range from those that form when there is an acute EPA Cold attack affecting the external regions of the body through to serious and chronic internal attack by Cold EPA. Of these the Tight pulse, Firm pulse and Hidden pulse can be arranged sequentially to reflect the continuation of a Cold EPA from the external regions of the body into the interior. (In addition to Cold EPA all three pulses also occur when there is stagnation of food, indicating a relationship/pathway between the pathology and their formation; see Fig. 8.2.)

|

| Figure 8.2Progression of Cold EPA from the exterior to the interior and consequent formation of likely pulse qualities. |

8.2.2.1. Slow pulse

A decrease in pulse rate is a generic change in the parameter of rate that occurs when Yang is affected causing pulse rate to slow. If the pulse rate falls to 60 bpm or less then this is the Slow pulse. A decrease in pulse rate is likely to occur in combination with the other pulse qualities listed above, when caused by a Cold EPA aetiology.

The Slow pulse is the simplest of the five traditional pulse qualities to recognise associated with a Cold EPA. Yet, a decrease in the pulse rate with Cold need not be so great as to cause the rate to fall to 60 bpm or less, the range ascribed for categorising the pulse rate as the Slow pulse. The Slow pulse can also occur from internal Yang problems which slows the pulse. This is termed Yang vacuity (or Yang deficiency). (Yang vacuous pulses are discussed elsewhere.) In this sense the Slow pulse alone is not diagnostically specific enough to differentiate between a Cold EPA and Yang vacuity. It is necessary to assess the presentation of other pulse parameters to do this. Pulse force is an important additional parameter for this purpose: an increased force occurring with a decrease in pulse rate would likely indicate an EPA of Cold, whereas a decrease in both pulse force and pulse rate indicates dysfunction arising internally from Yang vacuity. When Yang is deficient the pulse sinks, being felt at a deeper level of depth than is normally felt for the affected individual.

Progression of Cold in the body

There are situations in which the body’s immune system is weak and so an EPA of Cold quickly goes internally and affects the organs directly. The digestive organs of the Stomach and intestines are prone to this occurring. In this situation, Cold continues to have its contracting affect, obstructing the free flow of Qi and blood. Fixed abdominal pain is symptomatic of this scenario. The formation of the Firm pulse or Tight pulse may result. The Firm pulse is a natural continuum of the Tight pulse when the Cold pathogen is either chronic or is causing severe pain.

The presence of Cold internally will counter the associated organ’s Qi or functional capacity, and eventually the body’s Yang. Eventually, a Yang vacuous condition will arise over time in spite of the initial problem having arisen from an ‘excessive’ Cold EPA. In time, the pulse continuum progresses from a pulse with strength to one without strength.

8.2.2.2. Tight pulse and Drumskin pulse

The two other Cold-related pulses are the Tight pulse and the Drumskin pulse. These are both complex pulse qualities, developing from changes in several pulse parameters. Both are distinctive pulses with their associated increase in arterial tension.

The Tight pulse can occur with general internal obstructive disorders associated with poor digestion, so needs to be carefully differentiated from its Cold causation with assessment of other signs and symptoms as well. Using the pulse parameters, a Tight pulse caused by Cold and the Tight pulse caused by obstruction (not necessarily Cold related) can be differentiated by changes in pulse rate. The Tight pulse will probably occur with a generic decrease in pulse rate when due to a Cold EPA. When food obstruction is due to Cold, which occurs in a situation where a Cold EPA goes internally and causes obstruction, then the Tight and Slow pulse will also manifest.

The Drumskin pulse can also occur in the presence of a Cold EPA, as is apparent in the increase in arterial tension due to vasoconstriction, but its formation is primarily due to tensile stress in other layers of the arterial wall due to underlying blood vacuity. When the blood and fluid levels are normal and a Cold EPA invades, then the Drumskin pulse will not occur (Box 8.5).

Box 8.5

Drumskin pulse and a Cold EPA

The Drumskin pulse is not necessarily about diagnosing blood vacuity, rather its main indication is that relating to Cold EPA. Clinically, treatment should be aimed at addressing the Cold EPA, not Blood vacuity. Herbs required for treating Cold EPA differ from those for Blood vacuity. If Blood-tonifying herbs are used, they may aggravate or cause a delay in resolution of the Cold EPA. Once the Cold EPA is expelled then the Drumskin pulse is likely to resolve into a pulse whose parameters are more typical of Blood vacuity.

8.2.3. Pulse qualities that reflect Heat

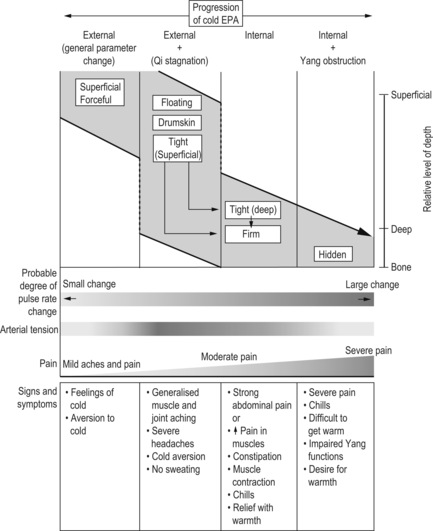

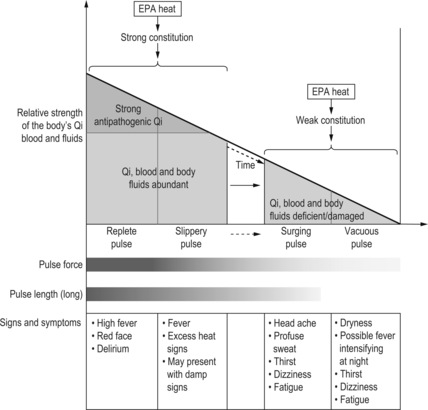

Heat by nature is expansive and supplements the normal functional activity of Yang in the body. Feeling hot, fever, sweating, flushed face are signs of pathogenic illness arising from Heat (Fig. 8.3). Heat additionally agitates blood and Qi, thus affecting the pulse.

|

| Figure 8.3Affect of an EPA Heat on pulse parameters and the formation of traditional pulse qualities with consideration to the relative strength of Qi and Blood (fluids). |

Heat affects the pulse in three ways.

• Pulse rate: Pulse rate is a reflection of the functional activity of Yang. As Heat adversely supplements the Yang, then pulse rate increases. From a biomedical perspective this is an increased activity of the cardiac cells in response to an increased metabolic rate affecting core body temperature.

• Pulse length: Heat adversely affects the normal flow of Qi and blood via its expansive heating quality. This is sometimes described as heat agitating the blood and Qi. The result is a pulse which extends beyond the Cun, Guan and Chi pulse positions. That is, the pulse becomes more apparent with palpation along its entire length and not just at these three pulse positions at the wrist.

• Pulse contour: Heat produces a variation in the pulse contour with a more distinctive pulse wave. Heat causes cardiac cells to contract more quickly and strongly, resulting in a more forceful pulse. From a CM perspective the change in the pulse from Heat EPA reflects the agitating affect of heat on Qi and Blood as core body temperature increases.

• Pulse force: Pulse force increases and is a direct reflection of the increased strength of contraction of the cardiac cells and subsequent increased stroke volume.

• Arterial width: By increasing the surface area of the artery the body attempts to lose more heat to the environment: a defensive mechanism to prevent heat from damaging the body’s Yin. Heat has an expansive action on the flesh and blood flow so the pulse wave contour comes to dominate the pulse quality and is felt wide.

• Level of depth: As a Heat pathogen invades the body so the body’s Qi responds by rising to meet the invading EPA. The pulse becomes relatively stronger at the superficial levels of depth. With Heat pathogens, the pulse is likely to be felt with strength at the other levels of depth as well.

There are five traditional pulse qualities attributable to the presence of a Heat EPA:

• Rapid pulse (section 6.5.2)

• Slippery pulse (section 7.9.1)

• Replete pulse (section 7.7.1)

• Vacuous pulse (section 7.7.3)

• Surging pulse (section 7.9.3).

Of the five traditional pulse qualities, the Rapid pulse is the simplest to recognise and will always reflect Heat. It is likely to combine with the other four pulse qualities when Heat pathogens are present. For example, the Slippery pulse due to Heat will have an increase in pulse rate, when this is >90 bpm, then the pulse is Slippery and Rapid.

The remaining four pulse qualities can be subdivided into two further categories. The first category includes pulse qualities in which the underlying Qi and blood are agitated but remain abundant:

• Slippery pulse (section 7.9.1)

• Replete pulse (section 7.7.1).

The second category contains pulses that are also associated with Heat pathology but have injury to the Qi and blood from the Heat pathogen:

• Vacuous pulse (section 7.7.3)

• Surging pulse (section 7.9.3).

8.2.3.1. Vacuous pulse and Surging pulse

The formation of the Vacuous pulse and Surging pulse is described in the classical literature as occurring as a result of Heat agitation of the Qi and blood but differs from the Slippery pulse and Replete pulse as Heat has also caused injury to the Qi and blood. This is reflected in the Vacuous pulse parameter of arterial occlusion, in which the pulse is easy to occlude. When pulses are easily occluded this indicates that the arterial or pulse volume (blood and fluids) is impaired. Impaired arterial volume causes decreased blood pressure, so that the resistance of the artery to finger pressure is also lessened. This is additionally noted by the lack of increased arterial tension that usually accompanies blood vacuity, indicating that the Qi is equally injured.

For the Surging pulse, the injured state of the Qi and blood caused by Heat pathogen is reflected in the diastolic segment of the pulse wave contour and in the parameter of pulse length. Unlike the Replete pulse and Slippery pulse, the Surging pulse is not felt beyond the Cun or the Chi pulse positions. That is, although heat is agitating the Qi and blood, these substances are not abundant enough to lengthen the palpable pulse beyond the three pulse positions.

The diastolic segment of the Surging pulse wave is described traditionally as ‘debilitated’, giving the sense that cardiac contraction should be strong causing a distinct sudden rise in the pulse wave hitting the fingers during systole, but because the blood and fluids are injured, no substance is present for the pulse force to continuing moulding the pulse contour during diastole, and so the pulse wave is not apparent.

The Surging pulse is sometimes described as felt ‘coming but not going’. This could also be interpreted as the pulse wave being felt hitting the proximal (body side) of the finger when palpating the pulse, but not felt going under the finger to the distal side (finger side).

An additional perspective on the formation of the Vacuous pulse and Surging pulse is that rather than Qi and Blood being damaged as a consequence of the heat Pathogen, the Qi and blood were already deficient before contraction of the Heat pathogen. As with the formation of the Drumskin pulse, it is the underlying vacuity of Qi and blood that may give rise to the Vacuous pulse and Surging pulse when Heat EPA occurs. When Qi and blood are abundant, then the Replete pulse and Slippery pulses are likely to occur instead.

Also, the Vacuous pulse and Surging pulse can indicate a prognostic and temporal progression of a Heat EPA. For example, if Qi and blood are abundant, then the Replete/Slippery pulse will form. As the heat injures these, then the Surging pulse and Vacuous pulse may arise.

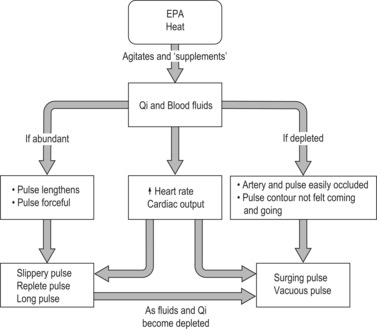

As a continuum, the Vacuous pulse and Surging pulse can arise from the Slippery pulse and Replete pulse when the heat begins to injure the blood, fluids and Qi. From this perspective there are prognostic guides that can be derived from these pulse groupings. For the Slippery pulse and Replete pulse, the Qi and blood remain uninjured so the patient will recover back to normal health and function once the pathogen is resolved. In contrast, the Surging pulse and Vacuous pulse represent an injury to the Qi and blood so recovery will be slower (Fig. 8.4).

|

| Figure 8.4Temporal progression of a Heat EPA and consequent formation of likely pulse qualities with respect to the relative strength of Qi and Blood (fluids). |

8.2.3.2. Slippery pulse and Replete pulse

Both the Slippery pulse and the Replete pulse form in the presence of Heat via the agitation of Qi and blood. Although the Qi and Blood are agitated by Heat, the formation of the pulses indicates that the Qi and blood remain strong and prognosis is good.

Both pulses are similar in the filling of the vessel, but the Slippery pulse has a distinct change in the pulse contour and is strong whereas the Replete pulse is felt equally strong at all three levels of depth. Characteristics of the two pulses may combine to form a unique pulse quality not adequately defined by either the Slippery pulse or Replete pulse definition.

8.2.3.3. Rapid pulse

The Rapid pulse is the simplest of these five pulse qualities, defined simply by an increase in the pulse rate parameter. The Rapid pulse can also occur from internal Yin problems; that is, dysfunction within the organs can lead to impaired Yin function causing a hyperactivity of the Yang and increasing the pulse rate. This is termed Yin vacuity (Yin deficiency). In this sense, increased pulse rate alone is not sufficiently diagnostic to differentiate between a Heat EPA and Yin vacuity and it is necessary to assess the presentation of other pulse parameters to do this. Pulse force is an important additional parameter for this purpose: an increase in force occurring with an increase in pulse rate is likely to indicate an EPA of Heat, whereas a decrease in pulse force occurring with an increase in pulse rate indicates dysfunction arising internally from Yin vacuity. Furthermore, the increase in pulse rate is pronounced for an EPA Heat, whereas for Yin vacuity the rate may increase but not substantially so.

8.2.4. Pulse qualities that reflect Wind

Only one pulse quality occurs with an EPA Wind attack, and even then, it is a generic pulse quality that can form in the presence of any EPA attack. This is the Floating pulse.

According to CM theory, Wind as a pathogenic agent often combines with other aetiology factors producing combinations of EPAs. For example, Wind can combine with Cold, Heat or Damp producing EPAs of Wind-Cold, Wind-Heat and Wind-Damp. In this scenario, a likely response of the pulse is to form pulses that reflect the other accompanying EPAs. This is a likely explanation for the paucity of Wind-specific pulses.

From a pulse parameter perspective, the parameter of arterial tension is related to Wind and could be used to identify Wind EPA. The parameter often presents as an increase in arterial tension. The Stringlike (Wiry) pulse, or variations of this in which there is an increase in arterial tension, were traditionally associated with Wind according to the classical writings of the Nei Jing. Sometimes, the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse was classically viewed as a healthy pulse when occurring in the season of spring (Unschuld 2003).

In contemporary times an increase in arterial tension is nearly always viewed as a pathological indicator of underlying tension and stress involving the liver. The increase in tension associated with liver dysfunction is still associated with the concept of Wind, but Wind arising internally. Wind can obstruct the free flow of Qi and blood. Conditions relating to internal Wind include stroke (transient ischaemic attack or cardiovascular accident) Parkinsonism, epilepsy and similarly related neurological conditions. Internal Wind is the result of chronic pathological processes affecting the blood and circulation of Qi. Stress and tension are readily linked to the concept as well. An increase in arterial tension relates to an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity and is a common response to pain.

8.3. Blood

In CM, blood is described primarily as having a nourishing or nutritive function, nourishing the skin, tissue and bones. A healthy quantity and quality of blood is required for maintaining concentration, emotional stability (poor blood can give rise to stress, tension, anxiety affecting the Shen) and is important in the restorative outcomes of sleep. Blood is also seen as the physical or denser aspect of Qi, yet it is inherently Yin because of the density and moisturising function that accompanies its nutritive capacity (Maciocia 2004). When Blood quality is compromised or its quantity depleted then the nourishing and moisturising aspect is also impaired, and this is reflected in the pulse.

The pulse is intrinsically linked with the flow of blood in the arteries. It is not surprising to realise that nearly one third of the traditional pulse qualities either relate directly to or have an association to the diagnosis of blood pathologies or conditions that impact on the blood.

Blood pathologies fall into three broad categories:

• Blood vacuity (deficiency)

• Blood stagnation

• Blood heat.

8.3.1. Blood vacuity

Blood is thought of as the internal volume of the artery that gives the vessel form. It would be natural to consider that the pulse width would decrease concurrently with Blood vacuity. However, the traditional pulse qualities commonly mentioned in relation to Blood vacuity differ considerably in their presentation. Some pulse qualities manifest with a narrow arterial diameter, as would be expected if the blood is ‘vacuous’, yet there are other pulse qualities which manifest with a wide arterial diameter in the presence of Blood vacuity. It is this contradiction that commonly causes confusion and difficulty when applying pulse findings within a diagnostic framework.

Blood vacuity in CM is defined by a specific grouping of signs and symptoms that occur in individuals in whom the blood quality and/or quantity is reduced or compromised, and the blood’s nutritive and moistening function is similarly impaired (Box 8.3). Additionally, when blood is impaired so Qi will be affected: blood no longer nourishes Qi, Qi becomes deficient and fails to move the blood. In this situation, when blood becomes vacuous so an individual’s energy levels are similarly decreased. This is clearly reflected in the lethargy signs and symptoms that manifest when Blood vacuity occurs. However, the accompanying Qi vacuity needs to be carefully differentiated from a primary Qi vacuity. This is important, as primary Qi vacuity with primary Blood vacuity often result in pulses with reduced tension in the arterial wall. When Qi vacuity is a consequence or secondary response to Blood vacuity, then arterial wall tension is often increased.

Box 8.3

Blood vacuity signs and symptoms

• Dizziness on rising from a seated or lying position

• Lethargy/tiredness

• Shortness of breath

• Palpitations

• Cold extremities: nose, hands, feet

• Poor PRR

• Dryness of skin, hair, eyes

• Difficult going to sleep and/or dream-disturbed sleep

• Pulse:

– Rate is often increased above the normal resting rate when severe

– Pulse is relatively easy to occlude (normal or wide width pulses)

– Decrease in pulse force

The causes of Blood vacuity are many and varied. They range from impaired blood production processes affecting the quality of blood through to the simple loss of blood from the body as occurs with trauma so affectingthe volume of blood. Other causes of Blood vacuity include:

• Poor nutritional intake affecting blood production

• Malabsorption of nutrients (due to inflammatory conditions affecting the small intestine, other inflammatory disease such as arthritis, genetic conditions, dietary-related such as alcoholism)

• Impaired blood production processes

• Blood loss (trauma, surgery, intestinal bleeding, menstruation, childbirth, tissue loss/destruction from burns or toxins) whether acute (haemorrhage) or chronic (insidious), and the blood loss is greater than that for which the body can replace it

• Increased demand for blood (growth, tissue repair/replacement, pregnancy and nursing)

• Destruction of blood through disease processes (e.g. malaria).

In addition to the cause of Blood vacuity, the physiologic response of the body to Blood vacuity varies depending on two additional factors. The first factor relates to the degree of Blood vacuity, whether mild or severe. The second factor is temporal, whether Blood vacuity develops acutely or chronically. For example, sudden severe loss of blood volume will cause the body to go into shock causing a Faint pulse or Stirred pulse (from a CM perspective) or a pulse termed the weak and thready pulse (from a biomedical perspective). In contrast, mild to moderate Blood vacuity that develops over a long time can present with few symptoms as the body’s physiological response adapts to cater to a reduced functional capacity of blood as it becomes vacuous (Rodak 2002: p. 208). In this situation, while the quality of the blood is affected, the maintenance of the arterial volume is balanced by the proportional increase in fluid to compensate. The pulse may present with an increase in arterial tension and be relatively easy to occlude.

Blood vacuity can also arise secondary to other pathological processes and so the pulse will not present discretely as one of the traditional pulse qualities. As with the formation of damp in the body, the underlying cause of Blood vacuity will dominate the clinical presentation of the pulse and Blood vacuity may only be apparent in the pulse because it is easy to occlude.

With this in mind, the range and severity of the underlying causes of Blood vacuity mean that patients with Blood vacuity arising from all causes will not be seen in general CM clinical practice; obvious examples include acute trauma-related blood loss, burns or toxic reactions. The traditional pulse qualities associated with these conditions will therefore not necessarily be seen unless the CM practitioner is working within a mainstream health system.

8.3.1.1. Anaemia

In biomedical practice the term anaemia is used broadly to describe Blood vacuity. Rodak (2002) states that anaemia results ‘when red blood cell production is impaired, red blood cell life span is shortened, or there is frank loss of cells’ (p. 212). A diagnosis of anaemia is made when blood chemistry indices, whether in combination or alone, fall outside a standard accepted reference range for normal healthy function and production of blood. The cause of anaemia is further differentiated through either visual examination of the red blood cells, with distinctive changes in their size and shape being diagnostic important indicators, or through further blood tests. Assessment of the patient’s signs and symptoms is also used to help identify anaemia and determine the cause.

Anaemia can be classified as either morphologic or pathophysiologic. Morphologic classification of anaemia refers to the morphology or the size and shape of the red blood cells. The pathophysiologic classification of anaemia relates to the mechanism associated with discrete pathology causing decreased production, destruction or loss of red blood cells (Rodak 2002). Using this classification system there are many forms of anaemia arising from illness, impaired metabolism, environmental, genetic and other external causes; for example, iron-deficiency anaemia. (Reference should be made to appropriate biomedical texts for in-depth discussions on this topic and for detailed classification methods used to identify the causes and subsequent differential diagnosis of types of anaemia.)

Iron-deficiency anaemia

Iron-deficiency anaemia occurs when the intake of iron is inadequate to meet the body’s requirements. It has three causes:

• Inadequate intake of iron

• Chronic loss of iron through bleeding

• Increased demand for iron.

An inadequate intake of iron requires time to affect the actual production of blood, because the body has excess iron in storage and when the circulating level of iron decreases more is released from the stored iron levels. It is only when these stored iron levels are depleted that morphological changes become apparent and anaemia results. Inadequate dietary intake of iron, growth and development, pregnancy, insidious loss of blood, heavy menstrual bleeding, stomach ulcers, nursing mothers and other pathology in which blood is lost all lead to iron-deficiency anaemia (Box 8.4).

Box 8.4

Diet and iron absorption

• Vitamin C assists the absorption of iron

• Caffeine inhibits the absorption of iron

• Alcohol consumption can cause folate deficiency

Iron is metabolised into ferritin, a form usable by the body, and this is used for the formation and function ofred blood cells. When ferritin levels fall, red blood cell morphology is affected. The moisturising and nutritive functions attributed to blood by CM begin to be compromised.

Ferritin is also used for the production of haemoglobin. Haemoglobin is the part of the red blood cell that binds with oxygen and carbon dioxide and transports these molecules throughout the body; oxygen is transported to tissue cells for metabolic use and carbon dioxide, a metabolic by-product, is transported to the lungs for excretion. Individuals with iron-deficiency anaemia who physically exert themselves get tired easily and have shortness of breath because of the reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Iron-deficiency anaemia also affects energy metabolism by the mitochondria, the cell components in which energy is produced. Adamson (2001) describes iron as a ‘critical element in iron-containing enzymes, including the cytochrome system in mitochondria’ and states that ‘without iron, cells lose their capacity for electron transport and energy metabolism’.

As described in previous chapters, the Qi is said to move the blood, which is made apparent in our discussions of the different pulses and theory. The blood nourishes the Qi and so it is now apparent that when Blood vacuity manifests, iron stores in the body are affected and so energy production is reduced.

8.3.1.2. CM pulse qualities associated with Blood vacuity

Eight traditional pulse qualities are associated with Blood vacuity:

• Scallion Stalk pulse – Blood vacuity

• Vacuous pulse – Qi and Blood vacuity

• Faint pulse- Sudden acute blood loss

• Fine pulse – Fluid or blood loss (and Damp)

• Soggy pulse- Fluid or blood loss (and Damp)

• Drumskin pulse – Blood vacuity complicated by Cold EPA

• Rough pulse- Blood vacuity and Essence vacuity

• Weak pulse – Blood vacuity and Yang vacuity

Of these eight traditional pulse qualities, the Fine pulse, Soggy pulse, Faint pulse and Weak pulse all present with a decrease in arterial width. In contrast, the Scallion Stalk pulse, Vacuous pulse and Drumskin pulse all present with no change or an increase in arterial width. The Rough pulse is characterised by variation in the pulse contour and blood flow.

The traditional pulse qualities associated with blood vacuity fall into three broad categories. The first category is those pulses occurring due to primary Blood vacuity:

• Scallion Stalk pulse

• Vacuous pulse

• Faint pulse

• Fine pulse

• Soggy pulse.

The second category is for pulses that are also associated with primary Blood vacuity but are, or can be, complicated by the addition of a pathogenic factor:

• Drumskin pulse: Seen as the Scallion Stalk pulse combined by a complication of Cold EPA. Pulse reflects primary deficiency.

• Fine pulse (section 6.13.1)

• Soggy pulse (section 7.7.6).

The third category includes those pulses that reflect secondary Blood vacuity, arisen as a consequence of other pathological processes. The pathology involves internal problems of the organs related to blood production, the extraction of nutrients for blood formation or the catalytic conversion of blood; that is, the Kidneys and the Spleen. These pulses include:

• Rough pulse (section 7.9.2)

• Weak pulse (section 7.7.5).

8.3.1.3. Pulse parameters

The presentation of pulse parameters that represent Blood vacuity are broad (Table 8.2). The parameters changes that occur with pulses that reflect Blood vacuity are a consequence of the pathogenesis.

| Slippery | Moderate | Wiry | Fine | Soggy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | ✓ | ||||

| Tension | ✓ | ||||

| Contour | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Force | ✓ | ||||

| Depth | ✓ | ||||

| Length | ✓ | ||||

| Width | ✓ | ✓ |

| Vacuous | Scallion Stalk | Drumskin | Rough | Weak | Faint | Soggy | Fine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | ||||||||

| Tension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Contour Force | ✓ | |||||||

| Superficial Depth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Middle or deep | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Length | ||||||||

| Width narrow | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Width not thin | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Occlusion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The common pulse parameter changes occurring with all Blood vacuous pulse include:

• Occlusion: Easy to occlude. Reduced blood concentration in the arterial volume causes a reduction in the density of blood and blood pressure reduces. The pulse is consequently easier to occlude.

• Force: Force is decreased as the density of blood decreases so the pressure wave does not propagate as strongly.

As previously noted, temporal factors of Blood vacuity development affect the physiological response of the body. This is particularly apparent in the development of Blood vacuity occurring over time, in which the body’s physiology adapts to the apparent decrease in blood. Thus in addition to changes in pulse parameters associated with the pulses listed under this rubric, there will be additional changes:

• Rate: Increases in heart rate and respiratory rate. This increases the circulation rate of blood. In this way, although there is a decrease in blood, the functional capacity of blood is maintained as it moves around the body faster.

• Strength of cardiac contraction: This increases, moving a larger amount of the remaining blood throughout the circulatory system.

To comprehend the reason for the manifestation of different CM pulse qualities with Blood vacuity it is necessary to consider two factors. The first is the interrelationship between body fluids and blood. The second concerns the distinction between blood, that which circulates in the blood vessels, and blood (referred to in the following discussion as red blood cells), as a vital substance within the CM context.

8.3.1.4. Body fluids and Blood

The relationship between blood and fluids is apparent in dehydration, or where fluid moves from the blood to replenish tissue fluids. The movement of fluid in this way does not affect the actual number of red blood cells. That is, although arterial volume is affected, there is no change in actual iron levels or oxygen-carrying capacity of the red blood cells. When fluid moves out of the vessels to replenish the tissue fluids, likely changes in pulse parameters include a decrease in arterial width.

Hypothetically, if this situation occurred, and the individual was actually deficient in red blood cells (Blood vacuity), then additional changes to pulse parameters would include a decrease in pulse force and the pulse would be easy to occlude. This happens because when red blood cell concentration falls, arterial pressure also falls and the blood becomes less viscous. This probably gives rise to the Blood vacuity pulses that are characterised by a decrease in arterial width. These include the Soggy pulse, Fine pulse, Faint pulse and Weak pulse. These four pulses are additionally complicated by other factors contributing to their formation.

This is reversed in the case of haemorrhage, where fluids move from the tissues in order to maintain a functional arterial volume for continuing blood supply to the vital organs. In this situation, there is an actual loss of red blood cells and iron levels are affected, because blood has been lost from the body. When fluid moves into the vessels to compensate, this further dilutes the remaining red blood cells and so the blood becomes vacuous – even though actual volume of fluids in the vessels has been restored. This also occurs over time as fluid moves into the blood vessels in an attempt to maintain blood pressure, as blood production processes are no longer able to maintain a normal concentration of red blood cells in circulation. This probably gives rise to the Blood vacuity pulses that are characterised by an increase in arterial tension and width. (The width of the pulse may become a little wider reflecting the relative Yang excess.) The Scallion Stalk pulse and Drumskin pulse each reflect this, especially with the increase in arterial tension, with the Drumskin pulse being additionally complicated by a Cold pathology (as discussed in section 8.2.2).

8.3.1.5. Increase in arterial tension: Blood heat arising from Liver hyperactivity due to vacuous Blood

In CM the blood, when not circulating, is stored in the Liver. (This has some relationship to the biomedical understanding of the liver’s biological role in recycling iron from old or damaged red blood cells.) Blood, being Yin in nature, has a consequential cooling affect on the Liver. As the Liver is prone to hyperactivity, this is a complementary outcome. When blood levels decrease or the functional aspect of blood is impaired, then the liver may become hyperactive. Hyperactivity of the Liver produces heat. As the blood is stored in the Liver, heat is transferred to the blood and blood heat arises.

Liver hyperactivity additionally affects the free flow of both Qi and blood. If the circulatory movement is affected then substances can stagnate and this can additionally give rise to Phlegm-Damp.

The effect on the pulse is an increase in arterial tension. This may present as the traditional Stringlike (Wiry) pulse quality or eventually go on to form the Scallion Stalk pulse or the Fine pulse. Alternatively, the pulse parameters need not necessarily combine into a recognisable pulse quality and the pulse will simply present with an increase in arterial tension.

Blood vacuity presenting with Liver hyperactivity is often accompanied by hot signs and symptoms related to the liver, in addition to the usual Blood vacuity signs and symptoms. These include:

• Easy to anger

• Disturbed sleep

• Dry red eyes

• Headaches, especially occipital, and worse in the afternoon

• Stress and tension

• Erectile dysfunction (men)

• Amenorrhoea (women)

• Acne.

Additionally, muscles and tendons ‘dry’, becoming sinewy and can give rise to or become prone to inflammatory conditions such as overuse injuries (tendonitis, for example).

Dietary-related factors are often an underlying cause in the manifestation of this type of Blood vacuity.

8.3.1.6. The Vacuous pulse

Like the other Blood vacuity pulses, the Vacuous pulse is easily compressed, but it differs from the other Blood vacuous pulses in that there is not necessarily a decrease in width nor a noticeable increase in arterial tension. This is because the pulse is also diagnostic of a primary Qi vacuity. If Qi is vacuous then the ability to maintain tension in the arterial wall is also compromised. This indicates that the underlying pathogenesis is likely to lie with the Spleen processes affecting both Qi and blood production. An EPA of Summer Heat is said to specifically cause the Vacuous pulse.

8.3.1.7. Shock and severe acute blood loss

Severe trauma-related blood loss may result in shock: a potentially life-threatening cascade of events as the circulatory system shuts down. Shock can also occur in chronic organ dysfunction involving the heart. Heart failure is associated with myocardial cell disease leading to premature cell death resulting in reduced cardiac output (Katz 2000: p. 3). A reduction in the heart organ’s capacity to maintain circulation causes blood pressure to fall. The heart continues to compensate by increasing heart rate, further stressing the heart. This can lead to shock (see section 7.4.2.1).

As blood volume decreases, the body compensates by shutting down the broader circulatory system (via sympathetic vasoconstriction) in an attempt to maintain cardiac output and blood flow in cardiac and cerebral circulatory systems.

In addition to loss of blood volume from trauma, conditions causing dehydration (diarrhoea, vomiting, sweating), and heart attack (acute onset) and cardiac failure (chronic onset) can lead to shock.

8.3.1.8. CM traditional pulses qualities indicating shock

The Stirred (Spinning Bean) pulse and the Faint pulse are the equivalent ‘shock’ pulses in CM associated with severe blood loss (in biomedicine this is termed the weak and thready pulse). The Skipping pulse may also present in shock but is more likely to manifest as a result of chronic pathology. Similarly with the Bound pulse; heart disease or disruption to the heart’s normal conduction system causing severe bradycardia (Slow pulse) can lead to shock.

The Spinning Bean pulse is characterised by one other factor; it is also a short pulse, presenting only in one of the three pulse positions. In the Chinese medical literature, the Guan positions is often stated as the position where this pulse presents. The consensus arises for two reasons. Firstly, much of the pulse literature source and reiterate their pulse definitions from the Mai Jing, a single literature source, so there is similarity between different sources of information in the contemporary literature. The other reason has a physiological basis, relating to the support the arterial structure receives. Severe blood loss causes a decrease in blood pressure, making it difficult to palpate a clear pulse image. As the radial artery at the Guan position has support from the styloid process, a pulse might still be detectable there, although imperceptible at the Cun and Chi positions.

In CM the term ‘shock’ also encompasses emotional conditions in which the person may be easily frightened, timid, or manifest anxiety conditions such as panic attacks.

8.3.2. Blood stagnation

The term Blood stagnation (stasis) evokes images of an inability of the blood to circulate or a blockage in the normal free flow of blood. The term can be applied generically to fixed localised pain, used as a descriptive term when bruising is observed, or used diagnostically for chronic and serious conditions of organ impairment and degeneration (involving kidney/heart/liver), tumours (growths or ‘masses’) or infertility (Box 8.6). As such, it is the degree of ‘stagnation’ that dictates the relative severity of a Blood stagnation condition and hence prognosis and treatment application. All Blood stagnation conditions are characterised by fixed pain and the quality of the pain is usually described as boring, penetrative, deep or stabbing.

Box 8.6

Blood stagnation signs and symptoms

• Fixed localised pain

• Stabbing or boring pain

• Interruption to the free flow of Qi and Blood

• Bleeding that is clotted and dark

• Purple tongue

Blood stagnation has both external and internal causal factors. Externally, it can arise from acute impact trauma producing visible bruising. Internally, it arises from obstructive causal factors involving the organs and/or interruption to the smooth, free flow of Qi and blood. Both are termed Blood stagnation, yet obviously the diagnostic and prognostic seriousness of the stasis will differ.

When occurring with internal causes, Blood stagnation can either be diagnosed as a primary problem or it may be a secondary consequence or sequela of other pathological processes. For example, when Qi becomes vacuous (deficient) then blood is said to stagnate, as the Qi is too weak to move the blood. Conditions affecting the warming function and outward movement of Yang can also result in Blood stagnation. An EPA of Cold is such a factor, affecting Yang in this way. Cold in this sense is classified as an obstructive agent and a causal factor in the development of Blood stagnation. Obstructive agents also causing Blood stagnation include food; whether this is because Cold counters the body’s digestion of food by countering the Yang function and so food remains undigested, or whether food literally obstructs the movement of blood, the end result is a diagnosis of Blood stagnation. That is, there are symptoms of fixed and stabbing pain.

8.3.2.1. Pulse qualities reflecting Blood stagnation (stasis)

Blood stagnation can be an extension of Qi stagnation and for this reason all five traditional pulse qualities associated with Blood stagnation are equally indicative of Qi stagnation. Interestingly, in spite of the number of conditions that can be classed under this heading, only three traditional pulse qualities are listed in the literature as relating to primary Blood stagnation:

Two additional pulse qualities are also associated with Blood stagnation due to secondary causes:

• Bound pulse (section 6.7.2)

• Short pulse (section 6.11.2).

There are three reasons for the limited range of Blood stagnation pulses:

• Blood stagnation always causes the same cascading affect on the body system, irrespective of the cause or individual traits. Hence the similarity in causal factors associated with the Tight pulse and Firm pulse, ranging from EPA through to food retention.

• Blood stagnation is often secondary to other conditions. As in all situations, the pulse reflects the primary condition rather than the secondary manifestation.

• Blood stagnation is associated with pain. Pain will inevitably produce an epinephrine (adrenaline)-mediated response from the sympathetic nervous system, causing arterial tension to increase. The increase in arterial tension imparts its signature on the pulse, which overrides more subtle changes in other pulse parameters and so limiting the formation of other pulses when Blood stagnation occurs.

8.3.2.2. Pulse parameters

Two pulse parameters demonstrate distinctive changes when Blood stagnation occurs:

• Arterial tension: This is increased

• Pulse contour: There is a loss of the smooth and regular contour shape of the flow wave.

An increase in arterial tension is not an unexpected effect on the pulse when Blood stagnation occurs. There are two ways of viewing this parameter change:

• Blood stagnation is characterised by fixed pain conditions. Pain always causes a sympathetic nervous system response from the body. Sympathetic nervous system responses cause increased contraction of the arterial smooth muscle, and so the arterial wall is felt distinctly palpable from the surrounding tissue. In this situation, the arterial tension is not reflecting stagnation of blood, but rather the pain the individual is feeling that has arisen from Blood stagnation.

• The arterial tension reflects the obstruction in the smooth flow of Qi that has occurred in the body region affected by Blood stagnation. Obstruction in the Qi’s smooth flow affects the Liver, and Yang Qi is agitated. Arterial tension increases as a result.

The change in pulse contour with Blood stagnation can also be viewed in two ways:

• The constraining effect that an increase in arterial tension has on the ability of the pulse wave form to expand the vessel.

• An obstructive condition affecting blood flow means there is a constant barrier to the regular unimpeded volume flow of blood. This also occurs if the heart is not contracting in a regular and smooth fashion. Severe pain can also cause heart irregularities, further contributing to the circulatory impairment.

Whatever the cause, propagation of the arterial pressure wave and blood flow is impaired and so the contour of the pulse is not constant or it is constrained (Box 8.7).

Box 8.7

Pulse parameter differences between Blood vacuity and Blood stagnation

• Blood vacuity: Associated with compensatory changes in the width of the arterial structure

• Blood stagnation: Associated with changes in the blood flow contour

8.3.2.3. Firm pulse and Tight pulse

The Firm pulse and the Tight pulse both occur in the presence of Cold pathogens and can also reflect the retention of food; both Cold and food retention can cause stagnation of blood and Qi. Each is accompanied by changes in the width, force and arterial tension parameters that are increased above normal. In terms of severity, the Firm pulse is the more serious of the two and is often described in the classical literature as occurring in the presence of severe pain. The Firm pulse also occurs in the deep level of depth and indicates an additional affect arising from either internal causes or constraint of Yang from expanding the pulse.

The Firm pulse could be argued to be a progression of the Tight pulse. As the obstructive nature of the Blood stagnation continues and becomes chronic, or as the Yang Qi begins to be affected by the causal factor of obstruction, notably Cold in this case, so Yang’s innate warming function is affected. If pain is severe, then the Firm pulse rather than the Tight pulse would form, reflective of the greater degree of stagnation.

The Tight pulse and Firm pulse can also be categorised with pulses that form when Cold pathogens invade the body. Accompanying signs and symptoms are therefore required to determine whether Blood stagnation is symptomatic of the Cold pathogen or whether the stagnation is arising from another process.

8.3.2.4. Bound pulse and Rough pulse

The Bound pulse represents blood and Qi stagnation that is specifically affecting the heart. Like the Firm pulse and Tight pulse, the Bound pulse may be the result of a Cold EPA affecting the free flow of Qi and blood. Food retention is noted in the pulse literature as a causal factor for the Rough pulse; it can constrain the flow of blood and Qi, leading to Blood stagnation. In this sense, the food is literally seen as compressing the arterial structures in the gut, exerting pressure from within the intestines and stomach, and physically obstructing the normal free smooth flow of blood. There would be a corresponding change in the parameter of pulse force if the Blood stagnation were arising from an obstructive factor. Yet, both the Bound pulse and Rough pulse can occur as a result of underlying vacuities also leading to Blood stagnation.

The Bound pulse occurs as a result of impairment of the heart organ’s rhythm function. As the organ is affected, Blood stagnation is better viewed as arising from Qi vacuity. The Rough pulse also has a likely vacuity component in its formation arising from an internal depletion of Kidney Essence. Both pulses in their basic form would present with decrease in pulse force and/or occur at the deeper levels of depth.

8.3.3. Blood Heat

Blood Heat arises from several other factors, often involving conditions causing heat in the body, whether this be intrinsic from dysfunctional problems or external from diet and pathogenic agents. There are three traditional CM pulse qualities associated with Blood Heat:

• Stringlike (Wiry) pulse (section 7.5.1)

• Long pulse (section 6.11.1)

• Replete pulse (section 7.7.1).

All three pulses are associated with an increase in pulse length being palpable beyond the Chi positions, and if severe, also beyond the Cun positions. As with any Heat condition, the increase in pulse length arises from the agitating nature of Heat on the Qi and blood causing the pulse to become prominent beyond the usual three pulse positions. With the Stringlike (wiry) pulse, there is an additional factor of agitation arising from the hyperactive nature of the Liver Yang.

There will likely be accompanying increases in pulse rate, with EPA Heat causal factors having a greater change in pulse rate, probably forming the Rapid pulse, whereas internal-related Heat may simply be an increase in rate above the individual’s normal resting rate.

As in any situation, if there is pain accompanying the Blood Heat, then an increase in arterial tension will result, irrespective of the Blood Heat arising from internal or external causes.

8.4. Qi

Qi is viewed as the motive force behind the movement and circulation of substances in the body. In this sense, Qi is broadly seen as ‘function’ in a CM health context, so any change in normal circulatory and physiological function is Qi related.

When viewed in clinical practice, Qi is further differentiated on the basis of two factors: Qi location and related physiological function.

• Qi differentiation based on location broadly relates to the tissue and organ structures and their related functions. For example, lung-related function is termed Lung Qi. When lung function is compromised and breathing is laboured, then the Lung Qi is seen as being affected. This can arise from internal causes, where the actual Qi physiology and production is impaired, or can result from external illness due to EPAs interfering with the normal function of Qi in the lungs.

• An example of differentiation based on physiological function is the classification of the body’s immune or defensive mechanisms as Defensive, antipathogenic or Wei Qi. An individual who is constantly sick is diagnosed as Wei Qi vacuous. The normal healthy functioning of the organs relies on Yuan Qi. When the organs become impaired and their physiological function declines, whether through illness or age, so the Yuan Qi is implicated. (The topic is discussed in greater detail in relevant CM textbooks.)

8.4.1. Qi and the pulse

To revisit a previous concept, within the traditional pulse qualities, Qi and blood are inextricably bound within the same continuum; what affects one will affect the other. This is bound in the idea of Blood nourishing Qi and Qi moving blood. For example, when blood is vacuous, so Qi is not nourished, and feelings of fatigue with exertion may manifest. When blood stagnates so Qi stagnates; sometimes Qi stagnation can lead to Blood stagnation.

The interrelationship of Qi and blood is reflected in the traditional pulse qualities; the same pulse can present when either Qi or blood is affected. This is exemplified in the Vacuous pulse, occurring when both Qi and blood are vacuous. Differentiation of the Vacuous pulse as either a primary Qi vacuity or a primary Blood vacuity depends on which signs and symptoms are dominating (whether Qi or blood), and is assessed against aetiological factors.

In assessing Qi by the pulses there is an additional factor to keep in mind. Qi cannot be quantifiably measured. As such, assessment of the Qi by the pulse is not about measuring Qi. Rather, the pulse is about assessing normal organ function and body processes and the relationship these have to the formation of the pulse wave. When the pulse changes then the related organ or processes associated with that change is implicated and so it is then inferred that the related Qi process isdysfunctional. This is based on theoretical, conceptual and physiologic models used within the CM paradigm. For example, if an arrhythmia is present then it is inferred that the heart Qi is affected; we are not feeling the actual heart Qi but rather inferring information about it from the change detectable in the pulse wave (Box 8.8).

Box 8.8

Rhythm and the heart

Changes in rhythm always infer that the heart organ, and heart Qi, is affected.

In this context, when there is compromised body function, whether internal or external, then Qi pathology is diagnosed. There are four categories of Qi pathology:

• Qi vacuity

• Qi stagnation

• Qi sinking

• Rebellious Qi.

Kaptchuk (2000) arranges these into two broad categories of pathology, Qi vacuity and Qi stagnation, with Qi sinking a subcategory of the former and Rebellious Qi a subcategory of the latter.

8.4.2. Qi vacuity

There are four traditional pulse qualities associated with primary Qi vacuity. There are several other traditional pulses that also represent Qi vacuity, however, Qi vacuity is a consequence of other pathological processes with these pulses. For example, it often accompanies Blood vacuity pathologies (as has been discussed).

These four pulse qualities and their associated Qi aspects are:

• Vacuous pulse: Primary Qi vacuity (postnatal)

• Scattered pulse: Yuan Qi/Ancestral Qi (prenatal) vacuity – postnatal replenishment

• Short pulse: Qi vacuity causing obstruction (or vice versa) – forceless and forceful versions.

The four Qi vacuity pulses can be further classified by the particular Qi type affected. In this sense, they are used as a guide to the general severity of the Qi vacuity and thus are used as a prognostic indicator. In order of increasing severity, they are:

• Vacuous pulse: Primary Qi vacuity develops; blood is also equally vacuous

• Intermittent pulse: This is strictly related to the vacuity of heart Qi and is defined by interruptions to the heart’s normal regular rhythm. (Severity is determined by the frequency of interruptions. The Bound pulse and Skipping pulse may also develop when the heart Qi is vacuous but are complicated by additional aetiological and pathological processes.)

• Short pulse: The Short pulse occurs with Qi vacuity when the Qi is no longer sufficient to expand the pulse across the three pulse positions and is felt at one or two positions only

• Scattered pulse: The Scattered pulse occurs when the body’s Yuan Qi is depleted. It can occur at the end stage of heart failure. There may be accompanying changes in pulse rate but the pulse usually is a poor prognosis.

Each of these four pulses is distinct in its presentation, with only the Vacuous pulse and Scattered pulse having some temporal relationship to each other in the relative severity of the Qi vacuity they reflect.

8.4.2.1. Vacuous pulse and Scattered pulse

The Vacuous pulse and the Scattered pulse both reflect Qi vacuity. They are similar in their presentation with a decrease in arterial force. The Scattered pulse is differentiated from the Vacuous pulse by additional changes in arterial tension. In particular, in the Scattered pulse arterial tension is absent; the Yang Qi’s ability to hold tension in the artery is diminished as Qi becomes dangerously vacuous, unable to move blood to expand the arterial wall. The Scattered pulse occurs with vacuity of Yuan Qi. In this sense, the Scattered pulse is probably a natural progression of the Vacuous pulse occurring over a long period of time. If underlying Qi and Blood vacuity are not addressed then organ function becomes affected. The heart is prone to such effects, with physiological changes that can eventually damage its efficient functioning.

8.4.2.2. Pulse parameters

In the context of pulse diagnosis, the Qi is the motive force that moves the blood. This manifests as:

• The regular forward motion of blood

• Longitudinal expansion of the pulse along the arterial length.

As such, Qi vacuity effects changes in the following pulse parameters:

• Rhythm: Qi is seen as a motive force, giving rise to and ensuring the regularity of the movement of both Qi and blood in the vessels. Vacuity of Qi, especially relating to the heart, will affect rhythm

• Length: Qi, in the form of the pulse pressure wave, activates the movement of blood causing it to expand across the pulse positions as it flows through the arteries. In this sense, vacuity of Qi affects the pulse ability of the pulse to expand along the length of the artery

• Force: The strength of Qi is inferred in the functional ability of the cardiac muscle to contract. Variations in Qi result in variations of pulse strength.

8.4.3. Qi stagnation

Any pathological process or external pathogenic factor can potentially cause obstruction and/or lead to, stagnation of Qi. In this sense, many of the traditional pulse qualities can be associated with this pattern. For example, the Short pulse is also associated with Qi stagnation but occurs usually as a result of obstructive factors or secondary to Qi vacuity. However, there is one pulse in particular that primarily reflects Qi stagnation. This is the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse (see Chapter 7 for further detail).

8.4.3.1. Pulse parameter

There is a change in one pulse parameter that primarily reflects stagnation of Qi (and even then the change is not specific to Qi but can occur with any form of stagnation). This is arterial tension: specifically, an increase in arterial tension.

As such, any pulse that presents with an increase in arterial tension is potentially associated with pathology affecting the free flow of Qi and hence, concurrently or consequently, blood. Liver-related conditions involving stress, frustration, tension or anxiety are associated with an increase in arterial tension. Pathogenic factors such as Cold and internal phlegm similarly affect the free flow of Qi and so arterial tension is similarly raised.

Pain is considered to be a symptom of stagnation generally, whether this is Qi or blood related. As such, an increase in arterial tension is a likely response when pain is present (Box 8.9).

Box 8.9

Arterial tension

Pain, whether physical, emotional or psychological in origin, causes an increase in arterial tension, irrespective of the initial cause.

8.5. Yin vacuity

Three traditional CM pulse qualities are associated with Yin vacuity (Yin deficiency):

• Fine pulse: Fluid related

• Floating pulse: Functional ability of Yin to counter Yang

• Soggy pulse: Fluids and functional Yin.

The three pulses are related; the thin width of the Fine pulse and the superficial level of depth of the Floating pulse combine to form the Soggy pulse. In this way, it is understandable that all three relate to the diagnosis of Yin vacuity as they overlap in the mechanisms associated with their formation.

As previously discussed, the Fine pulse is the prototype of the Soggy pulse. They are both defined by a narrow arterial width, reflecting the loss of ‘fluid’ volume from within the arteries.

The Floating pulse occurs at the superficial level of depth, as does the Soggy pulse. Indeed, if the pulse is only felt strongest at the superficial level of depth and is accompanied by decreases in width and force, then this is the Soggy pulse. A pulse felt strongest at the superficial level of depth occurs during Yin vacuity because Yang floats, no longer adequately anchored by Yin.

The occurrence of any of the three pulses in a patient is not a definitive diagnosis of Yin vacuity as all three pulse qualities can occur during other pathological processes so other signs and symptoms should be taken into account (see below). From a pulse diagnosis perspective the parameter of pulse force is an ideal parameter to distinguish Yin vacuity from these other pathological processes.

When these three pulse qualities occur as a consequence of Yin vacuity the pulse force is often diminished, reflecting the vacuous nature of the process occurring. This also means that Yin vacuous pulses are often not detectable at the deep level of depth. Pulse rate also provides a further diagnostic indicator as to the process occurring. As Yin is vacuous then there is a relative excess of Yang and the activity of Yang is no longer restrained. Therefore, increases in pulse rate are likely to accompany Yin vacuity when heat signs also occur.

From a pulse parameter perspective the three pulse parameters that are most associated with conditions of Yin vacuity are:

• Arterial width: Decreased

• Level of depth: Superficial level of depth is strongest (but overall forceless)

• Rate: Increased when Yin vacuity is accompanied by heat signs.

Other associated signs and symptoms of Yin vacuity include:

• Night sweats

• Malar flush

• Insomnia

• Restlessness

• Five hearts hot (hands, feet and chest)

• Tidal fever

• Bright red tongue with no coat.

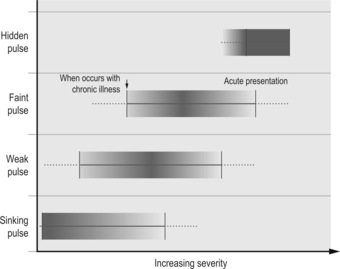

8.6. Yang vacuity

Four traditional CM pulse qualities may be associated with Yang vacuity:

• Sinking pulse (section 6.8.2)

• Hidden pulse (section 6.8.3)

• Faint pulse (section 7.7.4).

• Weak pulse (section 7.7.5)

In their vacuity form, the Sinking pulse, Hidden pulse and Weak pulse are all strongest at the deep level of depth, but are overall forceless at this level. This is because Yang is vacuous and so is unable to lift the pulse to the superficial levels of depth, while the strength of heart contraction (functional Yang) is not occurring.

The Faint pulse also represents Yang vacuity but is often described as occurring at any level of depth. This is because the Faint pulse also occurs with other vacuity patterns, especially Blood vacuity, and so it is difficult to definitively state its ‘normal’ level of depth. Depending on what vacuity is dominating, then the level of depth will vary. However, if Yang vacuity is dominating then this pulse may also be felt at the deep level of depth due to the same mechanisms as occurs in the vacuity forms of the Sinking pulse and Hidden pulse.