23 General operative principles

This chapter details many aspects of safe surgical practice common to all specialties.

Minimisation of infection

Fundamental to keeping bacterial contamination to a minimum is theatre design and the concept of asepsis (Box 23.1). Operating theatres are divided into zones including the transfer zone, the clean zone, the sterile zone and the disposal zone. The ventilation system of the operating theatre permits temperature control and humidity, air filtration to remove microorganisms, movement of air from clean to less clean areas and rapid and non-turbulent air change. Twenty to thirty changes per hour is usual. Infection control is achieved by sterilisation of instruments and equipment, skin preparation and draping of the patient, preparation and clothing of the operating team.

Box 23.1 Infection control

Sterilisation – a process that involves the complete destruction of all microorganisms, including bacterial spores

Disinfection – reduces the number of viable microorganisms but does not necessarily inactivate viruses and bacterial spores

Cleaning – a process that physically removes contamination but does not necessarily destroy microorganisms e.g. hand-washing (see p. 335).

Infected and other high-risk patients

The common positions for operations are listed in Table 23.1. Careful positioning is important, not only for access to the operating site, but also for prevention of nerve injuries which can occur as a result of traction pressure; for example, the brachial plexus and ulnar nerve, radial nerve and common peroneal nerve may all be damaged by careless positioning of the patient.

| Position | Use |

|---|---|

| Supine | Suitable for many operations |

| Prone | Back surgery |

| Trendelenburg | |

| Supine, but patient tilted 30–40° head-down | Pelvic organs; small intestine moves out of the way with gravity |

| Reverse Trendelenburg | |

| As Trendelenburg but tilt head-up | Upper abdominal organs |

| Lloyd-Davies | |

| As Trendelenburg but with legs abducted and hips and knees slightly flexed and legs in rests | Combined procedures involving abdomen and perineum (usually on distal large bowel) |

| Lithotomy | |

| Supine, hips and knees fully flexed, feet in stirrups or straps | Access to anal and perianal regions and external genitalia, vagina and uterine cervix, urethra and bladder (endoscopic) |

| Lateral | |

| Extension on right or left side with uppermost arm raised above and in front of head. Centre of table may be angled (broken) to improve access | Operations on kidney and in chest |

| Bowie | |

| Prone with flexion at hips | Access to perianal area |

Wound closure

This can be achieved in a number of ways:

• plastic surgery procedures to close defects which cannot be treated with the above methods, e.g. skin grafting, flap transfer (see Chapter 18).

Needles

• Straight needles are hand-held and are typically used to close skin edges in a subcuticular technique

• Curved needles are usually held in a needle holder but very large needles exist for hand-held use. Curved needles can have cutting or round-bodied points. Cutting edges are designed for closing wounds and can penetrate fascial layers. Round-bodied needles are used for suturing bowel, vessels and nerves, and are the needles used in microsurgery. They are designed to push tissues aside instead of cutting through them.

Sutures

There are two types, absorbable and non-absorbable.

Absorbable

• Broken down by the body by hydrolysis

• No foreign material left in wound once absorbed

• Reduced wound infection rate as organisms not trapped in suture material indefinitely

• May be absorbed too quickly before wound has regained tensile strength

• If broken down too quickly in infected wound, may lead to secondary haemorrhage

Non-absorbable

• Retains strength for long periods

• Natural (silk, metal) and synthetic (nylon, Prolene, Ethibond) materials are available

• Promotes foreign body reaction and organisms can become trapped around braided suture materials for long periods of time. Infected sutures often have to be removed for infection to clear completely

• Synthetic monofilament sutures are ‘slippy’ and harder to handle and tie than the natural braided versions. However, they slide through tissues easier than their braided counterparts, causing less local trauma to tissues.

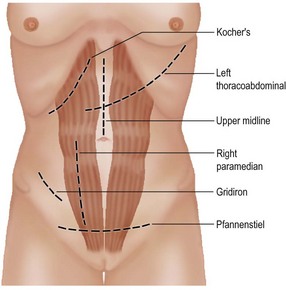

Access and common incisions

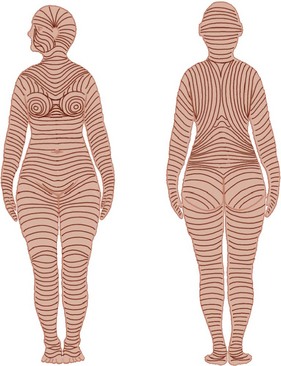

The correct incision must be made to allow adequate access to the operative field. Important considerations for incisions include sound healing and minimal pain during recovery with minimal complications and a satisfactory cosmetic result. Skin incisions, if possible, should follow the skin cleavage lines as described by Langer (Fig. 23.1). Abdominal incisions are shown in Figure 23.2.

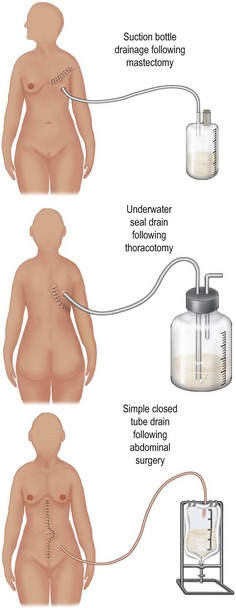

Drains

Drains are inserted to evacuate established collections of pus, blood or fluid. They range from simple wicks to low pressure suction applied to tubes. There is controversy concerning their use, with advocates maintaining that drainage of fluid collections removes potential sources of infection, guards against further fluid collections and alerts the surgeon to the presence of leaks or haemorrhage. However, the presence of a drain may increase the chance of infection and can cause damage to nearby structures. In many cases, they are ineffective after a few hours. The different types of drain in common use are shown in Figure 23.3. Most drains in modern surgical practice are closed in nature.

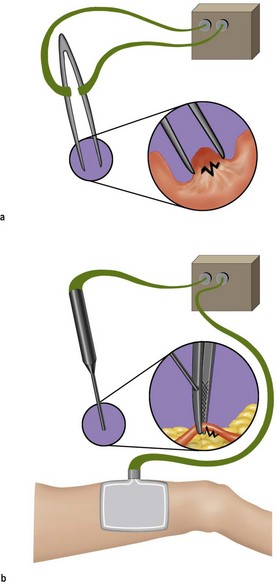

Haemostasis

The three main techniques used in stopping haemorrhage are compression, ligation and thermal coagulation. Compression via packing is particularly useful if there is widespread oozing. Ligation may be achieved by the use of haemostats and ligatures, either absorbable or non-absorb-able. Ligation may also be achieved by the use of stainless steel clips carried on special forceps. Thermal coagulation is achieved by the use of diathermy (Fig. 23.4). The electrical current pathway is either from the point of application through the body of the patient to a large area of contact plate and thence to earth (unipolar) or between two points of the instrument (bipolar). Small blood vessels can be precisely dealt with by either technique. A newer development is the employment of bipolar energy and mechanical compression to reliably seal vessels up to 7 mm in diameter (LigaSure™).

hours, the tourniquet should be released for 10–15 minutes and bleeding controlled by elevating the limb. Before closing the wound, the tourniquet should be released to ensure that meticulous haemostasis is achieved on completion of the operation. Elevation of the limb for up to 5 days following tourniquet procedures helps to prevent postoperative swelling. Tourniquets should not be used if patients suffer from peripheral vascular disease or sickle cell disease.

hours, the tourniquet should be released for 10–15 minutes and bleeding controlled by elevating the limb. Before closing the wound, the tourniquet should be released to ensure that meticulous haemostasis is achieved on completion of the operation. Elevation of the limb for up to 5 days following tourniquet procedures helps to prevent postoperative swelling. Tourniquets should not be used if patients suffer from peripheral vascular disease or sickle cell disease.