1 General issues and legal aspects

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based surgery is not restricted to randomised trials and meta-analyses but involves tracking down the best external evidence available to answer clinical questions or problems (see Box 1.1). For example, to find out about the accuracy of a diagnostic test, we need to find proper, cross-sectional studies of patients clinically suspected of harbouring the relevant problem and not a randomised trial. Proper follow-up studies of patients inform about prognosis. Systematic review of several randomised trials (meta-analysis) is much more likely to inform about therapy and whether it does more good than harm.

Box 1.1 Examples of classification systems for levels of evidence

The GRADE Working Group, 2004

High = Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate = Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low = Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

United States Preventive Services Task Force, 1989

Level I: Evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomised controlled trial

Level II-1: Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomisation

Level II-2: Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than one centre or research group

Level II-3: Evidence obtained from multiple time series with or without the intervention. Dramatic results in uncontrolled trials might also be regarded as this type of evidence

Level III: Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees

National Health Service

Level A: Consistent randomised controlled clinical trial, cohort study, all or none, clinical decision rule validated in different populations

Level B: Consistent retrospective cohort, exploratory cohort, ecological study, outcomes research, case-control study; or extrapolations from level A studies

Level C: Case-series study or extrapolations from level B studies

Level D: Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or first principles

Clinical governance and audit

Clinical governance

A widely used definition of clinical governance is:

• clinical effectiveness activities including audit and redesign

Healthcare organisations should achieve good clinical governance by:

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)

This is an NHS organisation set up in 1999 to ensure everyone has equal access to medical treatments and high quality care from the NHS. It is responsible for providing national guidance for promotion of good health and for the prevention and treatment of ill health. These are often referred to as ‘NICE guidelines’; these are easily accessible via www.guidance.nice.org.uk.

Patient safety: the WHO surgical safety checklist

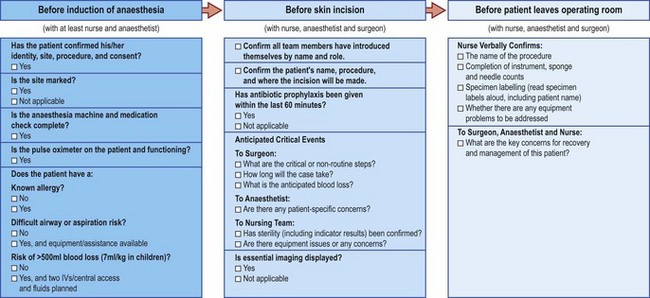

This simple yet effective tool has been introduced around the world by the World Health Organisation and is thought to have already saved many lives (Fig. 1.1).

Peer review

For audit to be meaningful, it should satisfy the following criteria:

• includes open debate and self-evaluation

• confidentiality of surgeon and patient maintained

• demonstration of change resulting in improvement of patient care

• resources spent are kept to a minimum

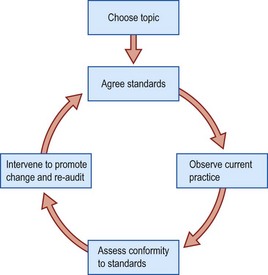

The audit cycle involves observation of existing practice, the setting of standards, comparison between observed and set standards, implementation of change, and re-audit of clinical practice (Fig. 1.2).

Informed consent

Complete informed consent includes a discussion of the following:

• nature of the decision/procedure

• reasonable alternatives to the proposed intervention

• the risks, benefits and uncertainties related to each alternative

Information considered adequate

The law in this area suggests one of three approaches:

• Reasonable physician standard – what would a typical physician say about this intervention?

• Reasonable patient standard – what would the average patient need to know in order to be an informed participant in the decision?

• Subjective standard – what would the patient need to know and understand in order to make an informed decision?

Breaking bad news

Sharing the information

• Assess the patient’s understanding and what they already know.

• Assess how much the patient wishes to know.

• Give a warning that difficult information is coming.

• Basic information should be given simply and honestly.

• Repeat important points if necessary.

• Do not give too much information too early.

• Give information in small chunks.

• Check repeatedly for understanding and the patient’s feelings as you proceed.

• Use language carefully with regard to the patient’s intelligence, reactions and emotions.

Being sensitive to the patient

• Assess non-verbal clues, for example face or body language, silences or tears.

• Allow the patient time and space, particularly when you feel they might have stopped listening.

• Give adequate breaks for the patient to ask questions.

• Assess if the patient needs further information and listen to their wishes – patients vary greatly in their need for this.

• Try to encourage expression of feelings, ‘giving permission’ for them to be expressed.

• Respond to these feelings with acceptance, empathy and concern.

• Try to elicit all the patient’s concerns.

• Be aware of unshared feelings, i.e. what cancer means for the patient compared with what it means for the surgeon.

Supporting the patient

• Offer to help break down overwhelming feelings into manageable concerns, prioritising and distinguishing the fixable from the unfixable.

• Identify a plan for what is to happen next within a broad time-frame.

• Give hope tempered with realism.

Closing the consultation

• Check with the patient that they understand what has been said.

• Do not rush the patient into treatment.

• Fix a further appointment if necessary.

• Identify support systems, which may involve relatives and friends.

• Offer to see or tell the spouse or others that whom the patient may wish you to communicate with.