GENERAL FIRST-AID PRINCIPLES

In all first-aid situations, the rescuer must remain calm. If you panic, you will lose control of the victim, as well as of yourself. To establish authority, speak and act calmly and purposefully. Allow the victim to discuss the incident, his situation, and his fears. If you can involve the victim in his rescue and treatment, it is often good for his morale. Try not to be judgmental, and save criticism for after the event. Avoid laying any blame on people; they may get hurt emotionally or become argumentative as a result. When communicating with a victim and bystanders, remember that you are not only caring for the victim, but in many ways, for family and friends. It is important to communicate frequently, honestly, and in a manner that is reassuring and inspires cooperation and hope.

Do not endanger additional inexperienced rescuers. If you cannot get to the victim easily, send for help. Approach all victims safely; don’t allow the sense of urgency to transform a sensible rescue into a series of risky, or even foolhardy, maneuvers. If it appears that the victim is too ill to be moved, set up camp immediately. In all cases, protect the victim from the elements from above and below.

If you have paper and a writing instrument, record your observations. If you send someone for help, have him carry a piece of paper that states the victim or victims’ location, the nature of the emergency, the number of people needing help, the condition of the victim(s), what is being done to treat the victim(s), and any specific environmental conditions or physical obstacles. Accident report forms are available from organizations such as The Mountaineers.

Always assume the worst. Assume that each victim you encounter has a broken neck or has had a heart attack until proven otherwise. Always be conservative in your treatments and recommendations for further evaluation or rescue.

Never move a seriously injured victim unless he is in danger from the environment or needs to be moved for medical reasons. Don’t encourage a victim to get up and “shake it off” until you have examined him for a potentially serious problem.

Never administer medicines or perform procedures if you are not sure what you are doing. The good Samaritan has certain legal protections for his actions so long as he operates within prudent limits and takes reasonable care. This book will not make you a doctor. A good rule to follow is primum non nocere: “First of all, do no harm.” If you are not certain what to do and the situation isn’t worsening, don’t interfere. Explain to the victim that you are not a physician, but will do your best to get him through whatever crisis he has encountered, to the best of your knowledge and ability. If you encounter a victim who may be seriously ill, seek an expert opinion as soon as possible. Even if your treatment seems successful, it is wise to consult a physician if you would have ordinarily done so.

Listen to the patient. The story of what happened and the medical history can be extremely important in making swift and appropriate medical decisions. Let the victim tell you what happened in his or her own words, and try not to interrupt unless it is important. If a victim has a sprained ankle, a comprehensive discussion may not be necessary, but if it is appropriate, try to elicit the following:

Gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting (describe what is vomited), diarrhea (describe consistency), red blood in stools or dark black stools, yellow skin (jaundice), perianal itching, constipation, excessive gas, bloating, belching

Hematologic/immune: anemia, frequent infections, exposure to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Genitourinary: change in frequency of voiding, painful urination, discolored or malodorous urine, back pain, blood in urine, history of sexual contacts, penile or vaginal discharge, date and character of last menstrual period (normal, abnormal), vaginal bleeding

Neurologic: seizure, weakness in any body part, numbness or tingling of any body part, difficulty with coordination or walking, difficulty with speech or comprehension, fainting

Muscular: muscle cramps, weakness, incoordination, pain

Psychiatric: abnormal thinking, hallucinations (visual or auditory), desire to hurt self or others, inappropriate crying or laughing, depression

EVALUATE THE VICTIM

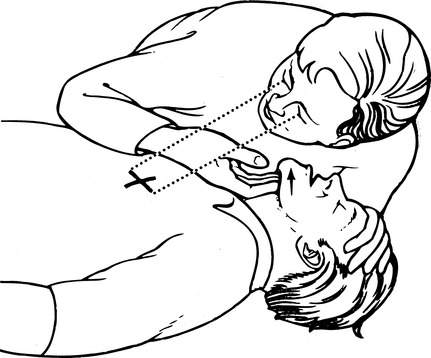

Look, listen, and feel for breathing (Figure 1). Put your ear close to the victim’s mouth and nose, and try to detect if he is moving air into and out of his lungs. Watch for chest wall motion. Determine if a victim is breathing by listening and feeling for air movement around the mouth and nose and observing the chest for unassisted rise and fall. In cold weather, look for a vapor cloud or feel for warm air moving across your hand. If the victim is not breathing well (or at all), you must manage the airway (see page 22) and begin to breathe for him (see page 28), taking care to maintain the position of the neck if there is any chance of a cervical spine injury (see page 37). Observe the number of breaths per minute; normal is 12 to 18 per minute for adults, 18 to 25 per minute for small children, and 25 to 50 per minute for infants.

Feel for a pulse. Current American Heart Association guidelines advise laypersons to begin chest compressions without going through a pulse check on victims who are not breathing and who do not show any sign of life. Basic life support may also be initiated by checking for a pulse. Place the tips of your index and middle fingers (not your thumb, which can generate a “false” pulse—your own!) gently on the radial artery in the wrist (see Figure 16, C, page 33). If you cannot detect a pulse there (particularly if your fingers are cold), move your fingers quickly to the brachial artery (this is particularly useful for infants) at the midpoint of the inside of the upper arm (see Figure 16, E, page 33), the femoral artery in the groin (see Figure 16, B, page 33), or the carotid artery in the neck (see Figure 16, A, page 33). If no pulse is detected in any of these locations (and the victim is not breathing or verbalizing), begin chest compressions (see page 32). Observe the pulse rate; normal is 55 to 90 per minute for adults, 80 to 110 per minute for small children, and 100 to 130 per minute for infants. The pulse rate is faster with excitement or fear and slower in trained athletes. A rapid and weak (“thready”) pulse is a sign of impending shock (see page 60), usually due to excessive bleeding, dehydration, or heart problems. An irregular pulse may indicate an abnormal heart rhythm.

Locate brisk bleeding. Quickly survey the victim to locate any obvious sources of brisk bleeding. Quickly apply firm pressure to these areas (see page 54).

If an injury may be extensive, examine the whole victim. Particularly dangerous situations include falls; blows to the head, neck, chest, or abdomen; altered mental status; difficulty breathing or shortness of breath; and injuries to children. In these cases, or whenever the diagnosis is not readily apparent, evaluate the victim from head to toe. Weather and appropriate modesty permitting, be sure to undress the victim sufficiently to perform a proper examination. Look around the neck or on the wrist(s) for a medical alert (such as MedicAlert) tag, and in a wallet, helmet, or pack for an information card.

Send for help early. As soon as you have determined that a situation will require extrication, rescue, or advanced life support, initiate your prearranged plan for communication and transportation. Don’t assume that someone will call for help; you must assign this task to a specific individual.