CHAPTER 6 General

Anaesthesia for the Elderly

Physiology

GI

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes

Therefore, ↓ VD for water-soluble drugs, ↑ VD for fat-soluble drugs.

Specific drugs

Barbiturates. Larger VD with prolonged clearance; 30–40% ↓ dose requirement.

Benzodiazepines (Table 6.1). Increased CNS sensitivity. High protein binding of diazepam results in greater free drug in elderly in contrast to lesser change in dose requirements of midazolam. The latter may cause severe hypotension in the elderly (Committee on Safety of Medicines warning).

| t1/2 (h) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Young adult | Elderly | |

| Diazepam | 24 | 72 |

| Midazolam | 2.8 | 4.3 |

Opioids (Table 6.2). Smaller VD with higher initial plasma concentrations. Increased elimination half-life (↓ clearance greater than ↓ VD). Decreased protein binding of pethidine with increasing age.

Table 6.2 Half-life of opioids

| t1/2 β (min) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Young adult | Elderly | |

| Alfentanil | 90 | 130 |

| Fentanyl | 250 | 925 |

General principles of anaesthetic management

Anaesthesia and Perioperative Care of the Elderly

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2001

Summary

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia and peri-operative care of the elderly, 2001. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Dodds C., Murray D. Pre-operative assessment of the elderly. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:181-184.

Rivera R., Antognini J.F. Perioperative drug therapy in elderly patients. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1176-1181.

Anaphylactic Reactions

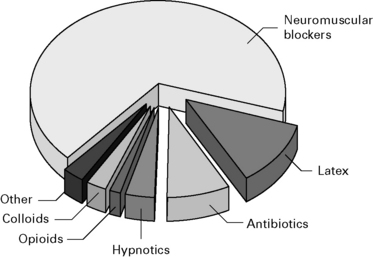

Hypersensitivity to drugs (Fig. 6.1)

In a French study (Laxenaire 2001), overall incidence of reactions was 1 in 13 000 anaesthetics, while the incidence of anaphylaxis to neuromuscular blocking agents was 1 in 6500 anaesthetics. Causes included neuromuscular blocking drugs (62%), latex (17%), antibiotics (8%), hypnotics (5%), colloids (3%) and opioids (3%).

Figure 6.1 Causes of life-threatening allergic reactions during anaesthesia.

(Data from Laxenaire 2001.)

Opioids

Usually cause anaphylactoid reactions. Mostly morphine. Reactions to synthetic opioids are rare.

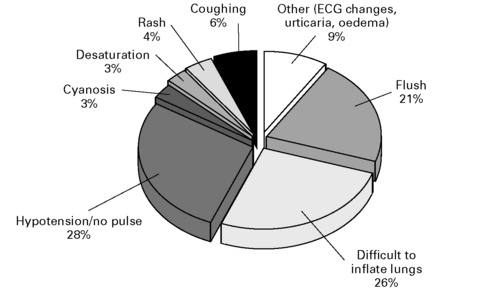

Clinical symptoms (Fig. 6.2)

Figure 6.2 The first clinical feature of an anaphylactic reaction.

(Data from Whittington and Fisher 1998.)

CVS. Arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension

Respiratory. Pharyngeal and laryngeal oedema (24%), rhinitis, pulmonary oedema

GI. Nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal colic

Treatment

Suspected Anaphylactic Reactions Associated With Anaesthesia

Treatment

Immediate management

Investigations

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Revised guidelines (4E), Suspected anaphylactic reactions associated with anaesthesia, 2009. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Fischer S.S.F. Anaphylaxis in anaesthesia and critical care. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;20:136-139.

Hepner D.L., Castells M.C. Latex allergy: an update. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1219-1229.

Laxenaire M.C., Mertes P.M., Groupe d’Etudes des Réactions Anaphylactoïdes Peranesthésiques. Anaphylaxis during anaesthesia. Results of a two-year survey in France. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:549-554.

Romano A., Pascal D. Recent advances in the diagnosis of drug allergy. Curr Opin Int Med. 2007;6:443-447.

Whittington T., Fisher M.M. Balliere’s clinical anesthesiology, vol 12. Elsevier, London, 1998;301-321.

Wildsmith J.A.W., McKinnon R.P. Histaminoid reactions in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:217-228.

Blood

Blood donors

Blood groups

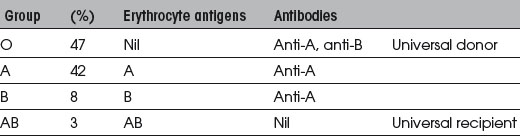

The ABO blood groups are summarized in Table 6.3.

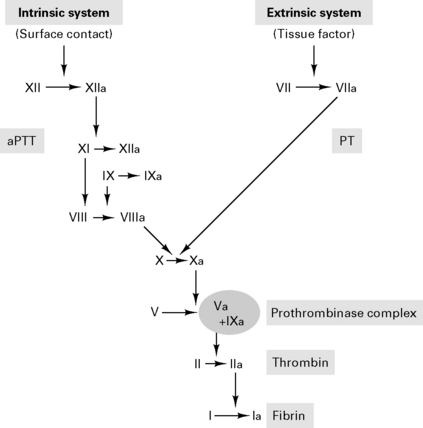

Coagulation cascade

Products

Whole blood

Platelet concentrates: 260 000 units used p.a. in the UK

Recombinant blood products

Recombinant FVIIa

rFVIIa initially developed to treat bleeding in haemophiliacs. FVIIa binds to tissue factor on damaged vascular beds to activate FIX and FX. The subsequent conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, activates platelets FVIII, FV and FXI and results in a large thrombin burst to transform fibrinogen to fibrin (Fig. 6.3). A recent meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials showed a reduction in blood transfusion requirements with no major safety concern (Ranucci 2008). Concerns remain regarding possible risks of thrombotic events.

Transfusion reactions

Acute

Delayed

Massive blood transfusion

Blood groups for urgent transfusion are:

Blood transfusions can be avoided by:

Guidelines for Autologous Blood Transfusion

British Committee for Standards in Haematology Blood Transfusion Task Force 1997

Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Red Cell Transfusion

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, June 2008

Summary

Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Blood Component Therapy

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, December 2005

Recommendations

Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Intraoperative Cell Salvage

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, September 2009

Recommendations

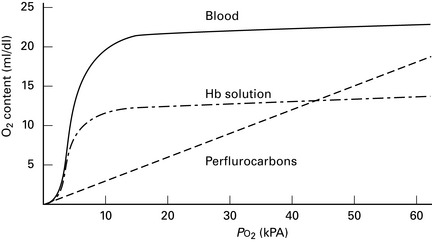

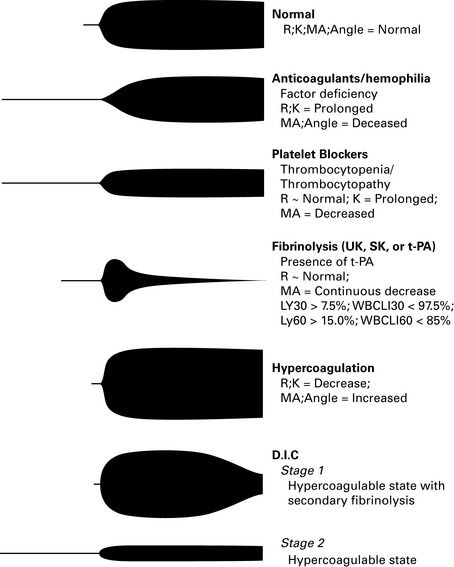

Artificial blood (Fig. 6.4)

Perfluorocarbons. Inert carbon chains with oxygen solubility 20 times that of plasma. One study showing that perfluorocarbon emulsion may limit transfusion requirements, but trend towards greater morbidity and mortality (Spahn et al 2005).

Postoperative care

Management of Anaesthesia for Jehovah’s Witnesses

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2005 (2E)

Consumptive coagulopathies

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Management of anaesthesia for Jehovah’s Witnesses, 2nd ed. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2005.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Red Cell Transfusion, 2008. June Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Blood Transfusion and the anaesthetist – blood component therapy, 2005. Dec Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Blood Transfusion and the anaesthetist – introperative cell salvage, 2009. Sept Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Bux J. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): a serious adverse event of blood transfusion. Vox Sang. 2005;89:1-10.

Contreras M., editor. ABC of Transfusion, ed 3, London: BMJ Publishing, 1998.

Mackman N. The role of tissue factor and factor VIIa in hemostasis. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1447-1452.

Martlew V.J. Peri-operative management of patients with coagulation disorders. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:446-455.

Maxwell M.J., Wilson M.J.A. Complications of blood transfusion. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:225-229.

Milligan L.J., Bellamy M.C. Anaesthesia and critical care of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2004;4:35-39.

Napier J.A., Bruce M., Chapman J., British Committee for Standards in Haematology Blood Transfusion Task Force: Autologous Transfusion Working Party. Guidelines for autologous transfusion. II. Perioperative haemodilution and cell salvage. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:768-771.

Ramanarayanan J., Krishnan G.S., Hernandez-Ilizaliturri F.J. www.emedicine.com/med/topic3493.htm, 2008. Factor VII

Ridley S., Taylor B., Gunning K. Medical management of bleeding in critically ill patients. 2007;7:116-121.

Serious Hazards of Transfusion Annual Report. www.shot-uk.org, 2008.

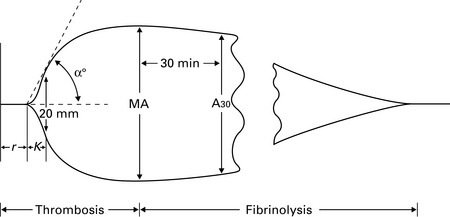

Shore-Lesserson L. Evidence based coagulation monitors: heparin monitoring, thromboelastography, and platelet function (Review). Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;9:41-52.

Silverman T.A., Weiskopf R.B. Planning Committee and the Speakers: Hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers: current status and future directions. Anaesthesiology. 2009;111:946-963.

Spahn D.R., Tucci M.A., Makris M. Is recombinant FVIIa the magic bullet in the treatment of major bleeding? Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:553-555.

Spahn D.R., Rossaint R. Coagulopathy and blood component transfusion in trauma. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:130-139.

Tanaka K.A., Key N.S., Levy J.H. Blood coagulation: hemostasis and thrombin regulation. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1433-1446.

Burns

Epidemiology

Systemic effects of burns

Tissue damage is due to both direct thermal injury and secondary damage from inflammatory mediators.

CNS. Encephalopathy, seizures.

Haematology. Bone marrow suppression, anaemia, thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy.

Skin. Increased heat, fluid and electrolyte loss. Loss of protective antimicrobial barrier.

Inhaled carbon monoxide and cyanide reduce tissue oxygen delivery.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes

Treatment of burn injury

Breathing

Carbon monoxide poisoning. 1000 deaths p.a. in the UK. The symptoms of CO poisoning are given in Table 6.4. HbCO results in over reading of the pulse oximeter. The half-life of carbon monoxide (250 times the affinity of O2 for Hb) is:

| %HbCO | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 0–10 | None |

| 10–20 | Headache, malaise |

| 30–40 | Nausea and vomiting, slowing of mental activity |

| >60–70 | CVS collapse, death. Consider hyperbaric O2 therapy |

Circulation

Blood loss during surgical debridement may be rapid and exceed 2 mL/kg per 1% of burn desloughed.

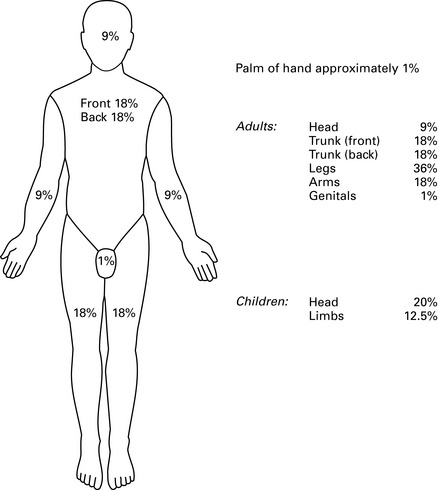

Extent and depth of burn

Burn size. This is estimated using the ‘Rule of Nines’ (Fig. 6.7).

Black R.G., Kinsella J. Anaesthetic management of burns patients. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:177-180.

Brazeal B.A., Traber D.L. Pathophysiology of inhalation injury. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1997;10:65-67.

Hilton P., Hepp M. The immediate care of the burned patient. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:113-116.

Latenser B.A. Critical care of the burn patient: the first 48 hours. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2819-2826.

MacLennan N., Heimbach D.M., Cullen B.F. Anesthesia for major thermal injury. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:749-770.

Pitkin A., Davied N. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:150-157.

Day-Case Anaesthesia

Advantages

General anaesthesia

Induction agents

Etomidate is rapidly metabolized but is associated with a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting.

Muscle relaxants

Use of neuromuscular blockers may reduce recovery time by decreasing volatile requirements.

Suxamethonium can cause myalgia for up to 4 days.

Brief laparoscopic procedures may be possible with spontaneous ventilation and face mask.

Neostigmine and glycopyrrolate increase the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Postoperative complications

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Revised 2005

Summary

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Revised Edition. Day surgery. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2005.

DoH. Day surgery. Operational guide. London: Department of Health, 2002.

Jackson I.J.B. The management of pain following day surgery. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:48-51.

Marshall S.I., Chung F. Discharge criteria and complications after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analges. 1999;88:508-517.

NHS Modernisation Agency. National good practice on pre-operative assessment for day surgery. London: NHS, 2002.

Rawi N. Analgesia for day-case surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:73-87.

Depth of Anaesthesia

Guedel classification

Described for spontaneous respiration with diethyl ether in 1937.

Monitoring depth of anaesthesia

Autonomic responses. BP, pulse and variability, sweating, dilated pupils.

Spontaneous skeletal muscle activity. Abolished with neuromuscular blockers.

General Topics

ASA grading (1963)

CEPOD classification of diseases

Prophylaxis of thromboembolic disease

Human immunodeficiency virus

The disease progresses through three stages:

Patients infected with the HIV virus present several anaesthetic problems:

Anaesthetists infected with HIV

The General Medical Council (1988) advise that any anaesthetist who thinks that he or she may be infected with the HIV virus must seek appropriate counselling and treatment. Anaesthetists infected with HIV risk infecting patients following blood-to-blood contact. The Department of Health (1993) has defined procedures that place patients at risk as:

Needlestick injury

Protection

Guidelines on Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (Pep) for Healthcare Workers Occupationally Exposed to HIV

HIV and Other Blood Borne Viruses

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 1992

Transmission and occupational exposure

HBV present in virtually all human fluids, particularly blood, semen and vaginal secretions.

Protection against HBV

All anaesthetists should be immunized against HBV, with boosters at 3–5 years.

Blood-Borne Viruses and Anaesthesia – an Update

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 1996

Anaesthesia and exposure-prone procedures

Exposure-prone procedures (replacing the term ‘invasive procedures’) are:

Transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) via the anaesthetic breathing system

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. HIV and other blood-borne viruses. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 1992.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Blood-borne viruses and anaesthesia – an update. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 1996.

Department of Health. Guidelines on post-exposure prophylaxis for health care workers occupationally exposed to HIV (Professional Letter: PL/CO(97)1). Wetherby, (West Yorkshire): Department of Health, 1997.

General Medical Council. HIV infection and AIDS: the ethical considerations. London: GMC, 1988.

Jackson S.H., Cheung E.C. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C: occupational considerations for the anesthesiologist. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2004;22:355-357.

Leelanukrom R. Anaesthetic considerations of the HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin Anaesth. 2009;22:412-418.

White E., Crosse M.M. The aetiology and prevention of perioperative corneal abrasions. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:157-161.

Diseases of Importance to Anaesthesia

Congenital syndromes

Haemoglobinopathies

Sickle cell disease

A Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death 2008

Principal recommendations

A Sickle Crisis? A report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2008 www.ncepod.org.uk/2008sc.htm.

Firth P.G. Anaesthesia for peculiar cells – a century of sickle cell disease. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:287-299.

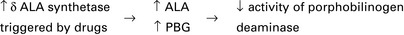

James M.F., Hift R.J. Porphyrias. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:143-153.

Martlew V.J. Peri-operative management of patients with coagulation disorders. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:446-455.

Other conditions

Infection Control

Guidelines – Infection Control in Anaesthesia

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2008

Healthcare organizations now have a legal responsibility to implement changes to reduce healthcare associated infections (HCAIs). The Health Act 2006 provided the Healthcare Commission with statutory powers to enforce compliance with the Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare Associated Infection (The Code). The Code provides a framework for NHS bodies to plan and implement structures and systems aimed at prevention of HCAIs. The Code sets out criteria that mandate NHS bodies, including Acute Trusts, and which ensure that patients are cared for in a clean environment. Anaesthetists should be in the forefront of ensuring that their patients are cared for in the safest possible environment. Further advice can be obtained from the Department of Health website: www.clean-safe-care.nhs.uk.

Summary

Mechanisms of Anaesthesia

Meyer–Overton theory

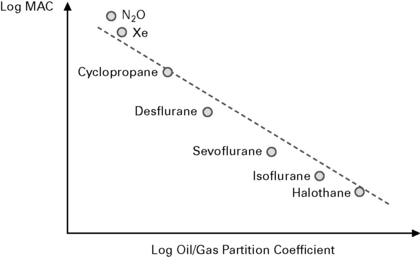

States that MAC × solubility = K (Fig. 6.8).

Hydrate hypothesis (Pauling and Miller 1961)

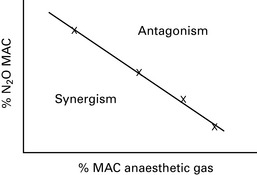

The fact that the brain consists of 78% water led to the suggestion that anaesthetics act on hydrophobic molecules. However, there is poor correlation between anaesthetic potency and water solubility. This theory also predicted that two anaesthetic agents would have a synergistic effect, but volatile agents appear only to have an additive effect (Fig. 6.9).

Multisite expansion hypothesis (Halsey 1979)

Hameroff S.R. The entwined mysteries of anesthesia and consciousness. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:400-412.

Hemmings H.C. Sodium channels and the synaptic mechanisms of inhaled anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:61-69.

Sonner J.M., Antognini J.F., Dutton R.C., et al. Inhaled anesthetics and immobility: mechanisms, mysteries and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesth Anal. 2003;97:718-740.

Weir C.J. The molecular mechanisms of general anaesthesia: dissecting the GABAA receptor. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:49-53.

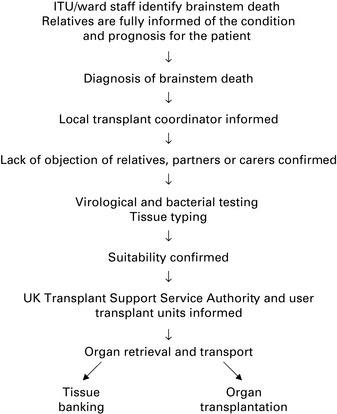

Organ Donation and Transplantation

Diagnosis of brainstem death

A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis of Brainstem Death

Brainstem testing

Diagnosis of brainstem death

All brainstem reflexes must be absent, i.e.:

Management of recipients for renal transplantation

(See also ‘Anaesthesia and renal failure’ section in Ch. 4.)

Management of recipients for cardiac/lung transplantation

Survival rates are improving as follows:

Similar anaesthetic technique to that for cardiac surgery.

Specific problems with management include:

Anaesthesia for non-cardiac surgery after heart/lung transplant

Baez B., Castillo M. Anesthetic considerations for lung transplantation. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;12:122-127.

Blasco L.M., Parameshwar J., Vuylsteke A. Anaesthesia for noncardiac surgery in the heart transplant recipient. Curr Opin Anaesth. 2009;22:109-113.

Colson P. Renal disease and transplantation. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1998;11:345-348.

Department of Health. A code of practice for the diagnosis of brain stem death, including guidelines for the identification and management of potential organ and tissue donors. Department of Health, London, 1998. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4009696.

Edgar P., Bullock R., Bonner S. Management of the potential heart-beating organ donor. BJA CEPD Rev. 2004;4:86-90.

Jennett B. Brain stem death defines death in law. BMJ. 1999;318:1755.

Morgan-Hughes N.J., Hood G. Anaesthesia for a patient with a cardiac transplant. BJA CEPD Rev. 2002;2:74-78.

Ozier Y., Klinck J.R. Anesthetic management of hepatic transplantation. Curr Opin Anaesth. 2008;21:391-400.

Pallis C., Harley D.H. ABC of brainstem death. London: BMJ Publishing, 1996.

Ramakrishna H., Jaroszewski D.E., Arabia F.A. Adult cardiac transplantation: a review of perioperative management (part I). Ann Card Anaesth. 2009;12:71-78.

Ramakrishna H., Jaroszewski D.E., Arabia F.A. Adult cardiac transplantation: a review of perioperative management (part II). Ann Card Anaesth. 2009;12:155-165.

SarinKapoor H., Kaur R., Kaur H. Anaesthesia for renal transplant surgery. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2007;51:1354-1367.

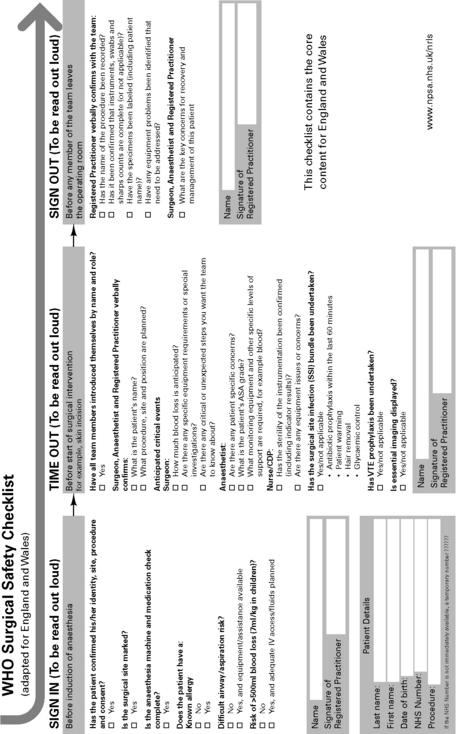

Patient safety

National Patient Safety Agency

Never Events, February 2009

Post-Anaesthetic Recovery

Discharge from the recovery room

The following criteria must be fulfilled:

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2002

Key recommendations

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Post-anaesthetic recovery. London: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2002.

National Patient Safety Agency 2009 Never Events. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/collections/never-events.

WHO Surgical safety checklist (adapted for England and Wales). 2009. http://www.safesurg.org/uploads/1/0/9/0/1090835/npsa_checklist.pdf.

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV)

Physiology

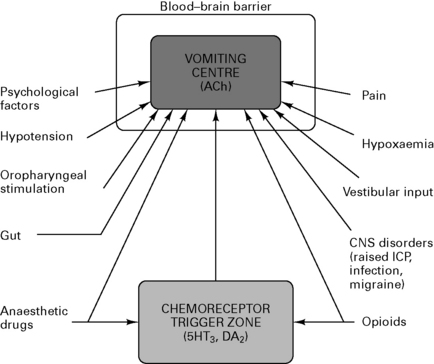

The vomiting centre is situated in the reticular formation of the medulla within the blood–brain barrier. The chemoreceptor trigger zone is situated in the area postrema on the floor of the IV ventricle and receives input from many afferents (Fig. 6.11).

Perioperative drugs causing PONV

Prevention

Kenny G.N.C. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1994;49(Suppl):6-10.

Naylor R.J., Inall F.C. The physiology and pharmacology of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1994;49(Suppl):2-5.

Kranke P., Schuster F., Eberhart L.H. Recent advances, trends and economic considerations in the risk assessment, prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:3217-3235.

Preoperative Assessment

Preoperative assessment should:

Investigations

Fasting guidelines (AAGBI 2001)

Preoperative Assessment. The Role of the Anaesthetist

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2001

Summary

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Preoperative assessment, The role of the anaesthetist, 2001. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Levy D.M. Preoperative fasting – 60 years on from Mendelson. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:215-218.

NHS Modernisation Agency. National good practice guidance on pre-operative assessment for day surgery. London: NHS, 2002.

NICE. Preoperative tests – The use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2003.

Royal College of Nursing. Perioperative fasting in adults and children, 2005 www.rcn.org.uk/publications/pdf/guidelines/perioperative_fasting_adults_children_full.pdf.

Resuscitation

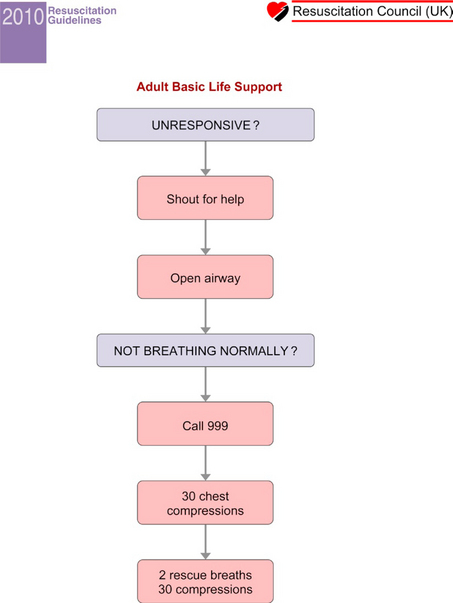

Adult basic life support guidelines

Basic life support is summarized in Figure 6.12a. The 2005 guidelines revised the compression:ventilation ratio to 30:2 following evidence that even short interruptions to external chest compression are disastrous for outcome. Compression-only CPR is acceptable if the rescuer is unwilling or unable to perform mouth-to-mouth ventilation.

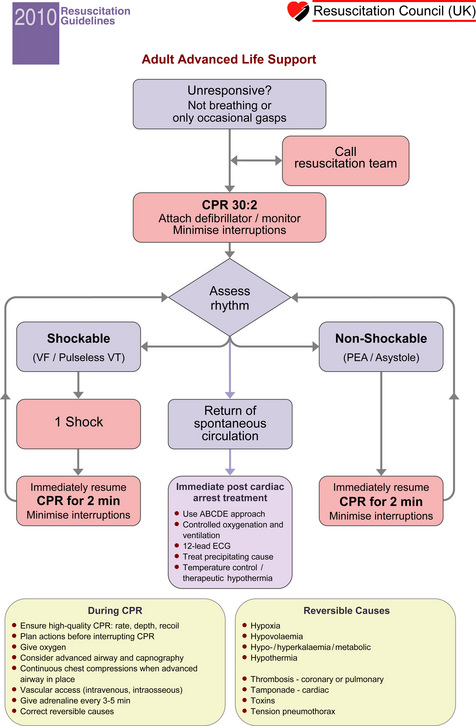

Figure 6.12 (A) Adult basic life support guidelines. (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010 © RC(UK).)

(B) Adult advanced life support guidelines. (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010 © RC(UK).)

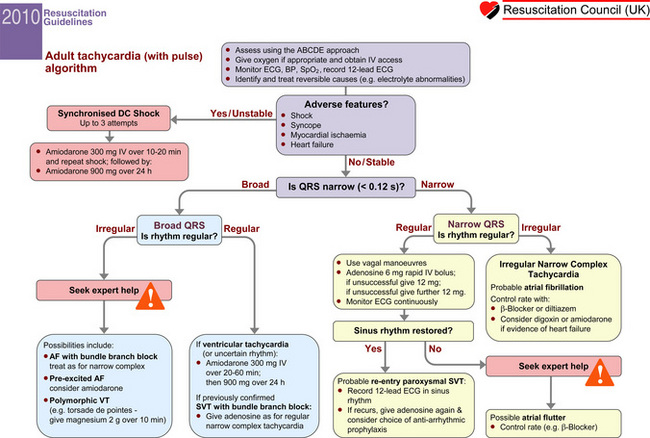

Adult advanced life support guidelines (Fig. 6.12b)

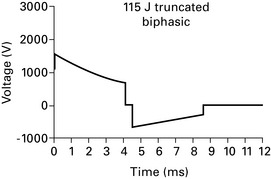

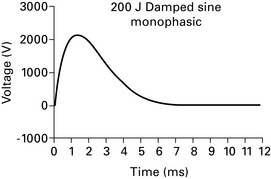

Defibrillation

Biphasic waveforms (Fig. 6.13) have the following advantages over older monophasic waveforms (Fig. 6.14):

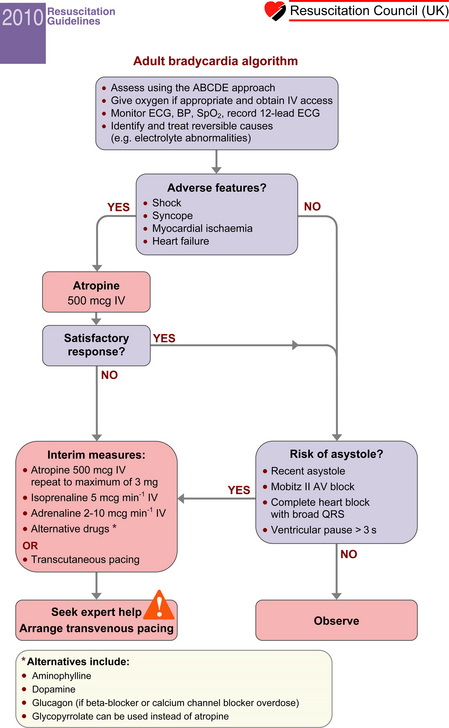

Atropine

Atropine is no longer recommended for routine use in asystole or pulseless electrical activity.

Post-resuscitation Care

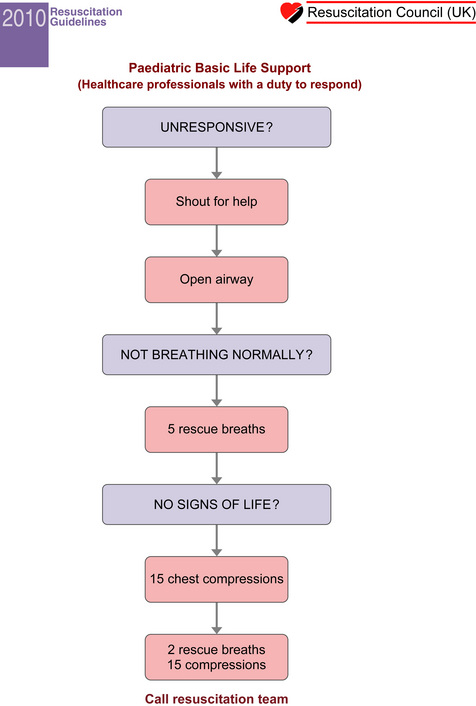

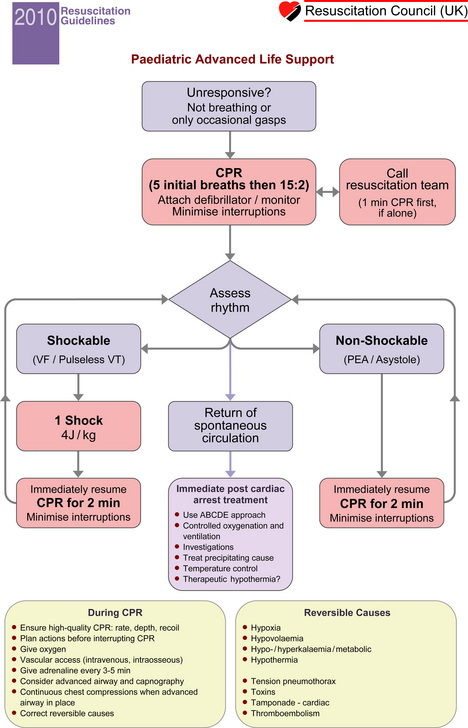

Guidelines for paediatric basic and advanced life support (Fig. 6.15a and b)

Figure 6.15 (A) Paediatric basic life support guidelines. (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010 © RC(UK).)

(B) Paediatric advanced life support guidelines. (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010 © RC(UK).)

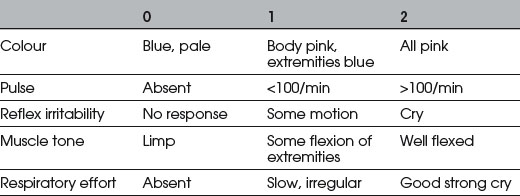

Apgar scores

Physiology of circulation during closed chest massage

There are two theories of blood flow:

Biarent D., Bingham R., Richmond S., et al. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation. Section 6. Paediatric life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67:S97-S133.

Bouch D.C., Thompson J.P., Damian M.S. Post-cardiac arrest management: more than global cooling? Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:591-594.

Deakin C.D., Nolan J.P., European Resuscitation Council. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation. Section 3. Electrical therapies: automated external defibrillators, defibrillation, cardioversion and pacing. Resuscitation. 2005;67:S25-S37.

Handley A.J., Koster R., Monsieurs K., et al. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation. Section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation. 2005;67:S7-S23.

Nolan J.P., Deakin C.D., Soar J., et al. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation. Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67:S39-S86.

Statistics

Normal (Gaussian) distribution

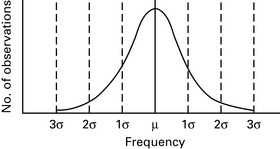

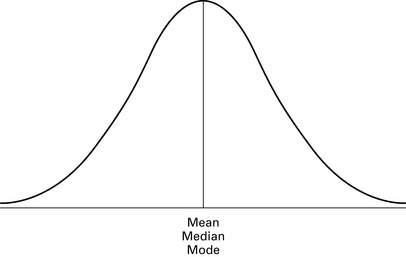

A sample of data may form a normal distribution curve which is bell-shaped and symmetrical about the mean value, e.g. height, weight, heart rate (Fig. 6.17).Mean, median and mode

The mean, median and mode have identical values within normally distributed data (Fig. 6.18a).

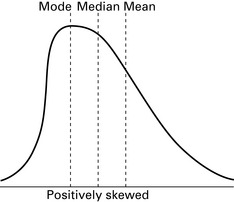

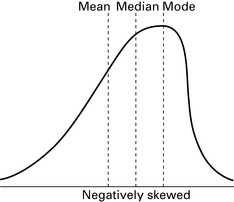

Curves of normal distribution have symmetry about the mean. A curve that is not symmetrical is referred to as skewed. A curve is positively skewed if most data lie below the mean, and negatively skewed if most data lie above the mean. In a skewed distribution, mean, median and mode are not equal (Fig. 6.18b,c). The amount of skewness is given by the following equation:

n – 1 = degrees of freedom (N).

Variance, standard deviation and standard error

The variance of a sample is a measure of the scatter about the sample mean:

Standard error (SE) is the standard deviation of the population mean:

Standard error of the mean (SEM)

Describes the deviation of the sample mean from the estimated population mean:

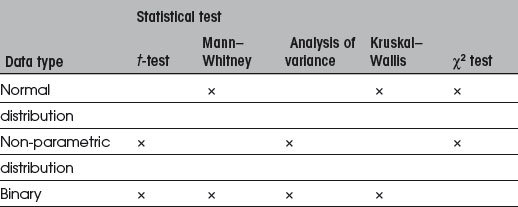

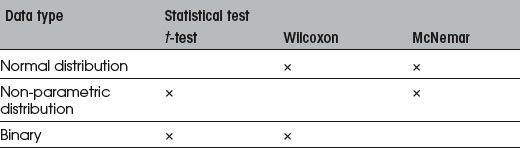

Statistical tests (Tables 6.6, 6.7)

Parametric tests

Significance values

Expressed as p-values, e.g. p = 0.01 means 1 chance in 100 that the results occurred by chance:

Linear correlation and linear regression

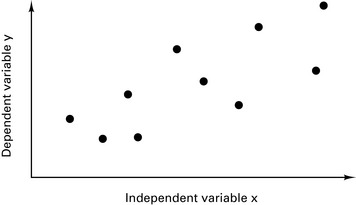

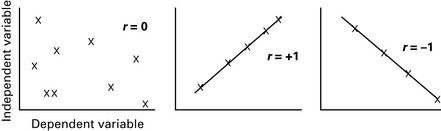

Observation of a scattergram may suggest some form of correlation between two variables (Fig. 6.19).

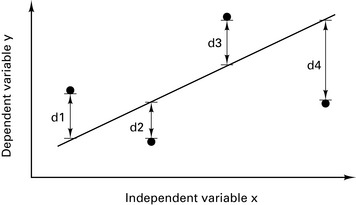

The best-fit straight line is calculated for the data (Fig. 6.20). The position of the best-fit straight line is adjusted to minimize the sum of the distances d1–d4 so that Σd is a minimum.

The best-fit line is given by the equation:

Correlation coefficient

The correlation coefficient, r, is an indication of how close the points lie to the best-fit line. As the data lie closer to the best-fit line, r tends towards 1.0 (Fig. 6.21).

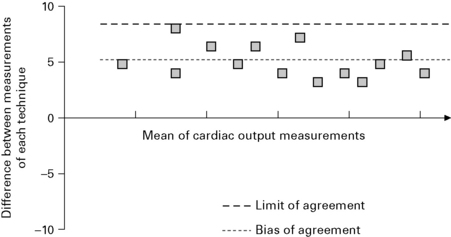

Bland–Altman plot

When comparing unrelated data, e.g. height versus weight, correlation coefficient is appropriate. When comparing related data (e.g. different methods of measuring the same variable), a Bland–Altman plot is more appropriate. The mean of each individual data pair is shown on the x-axis and the difference between each data pair on the y-axis. An example is given in Figure 6.22.

Types of clinical studies

Retrospective

Prospective

Gardner M.J., Altman D.G. Statistics with confidence. London: British Medical Association, 1989.

McCluskey A., Lalkhen A.G. Statistics I: data and correlations. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:95-99.

McCluskey A., Lalkhen A.G. Statistics II: Central tendency and spread of data. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:127-130.

McCluskey A., Lalkhen A.G. Statistics III: Probability and statistical tests. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:167-170.

McCluskey A., Lalkhen A.G. Statistics IV: Interpreting the results of statistical tests. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:208-212.

McCluskey A., Lalkhen A.G. Statistics V: Introduction to clinical trials and systematic reviews. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;8:143-146.

Swinscow T.D.V. Statistics at square one, ed 8. London: British Medical Association, 1983.

Trauma Management

A Royal College of Surgeons Working Party (RCS 1988) highlighted serious deficiencies in trauma patient management.

A Major Trauma Outcome Study (MTOS) was published in 1992 with similar conclusions:

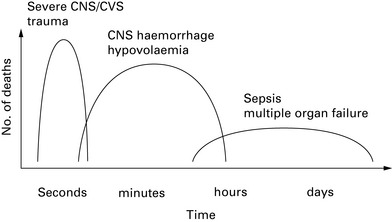

Trunkey described a trimodal pattern of death seen after major trauma (Fig. 6.23). The first peak comprises patients with serious, generally non-survivable injuries. The second peak comprises patients with life-threatening injuries in whom prompt, appropriate treatment may be life-saving. It is these patients to which the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol is directed. The third peak comprises patients who die several days/weeks later from sepsis or multiple organ failure.

Advanced Trauma Life Support

Primary survey

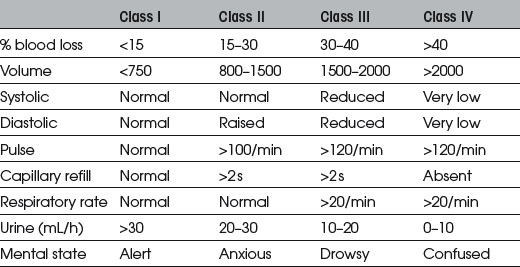

Classification of hypovolaemic shock

Intravenous access

Fluids in resuscitation

Type of fluid

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, September 2007

Investigation for injuries to the cervical spine

Which investigation?

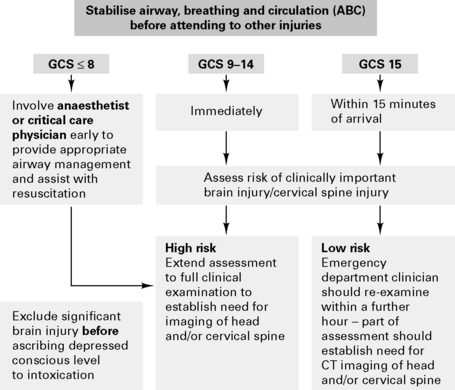

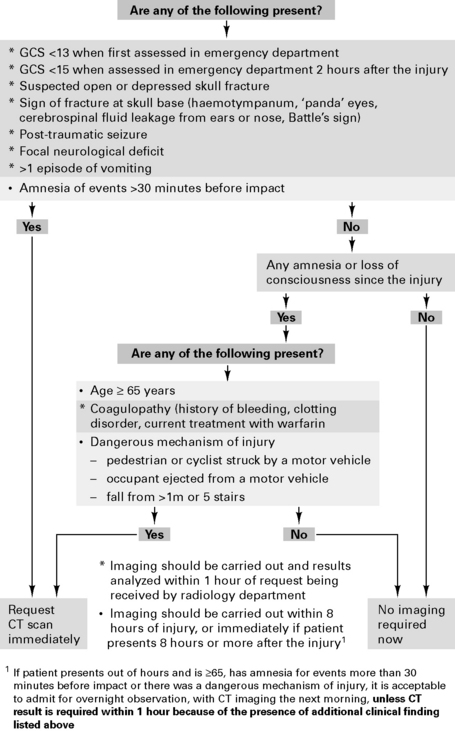

Figure 6.25 Selection of adults for CT scanning of the head. (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence.)

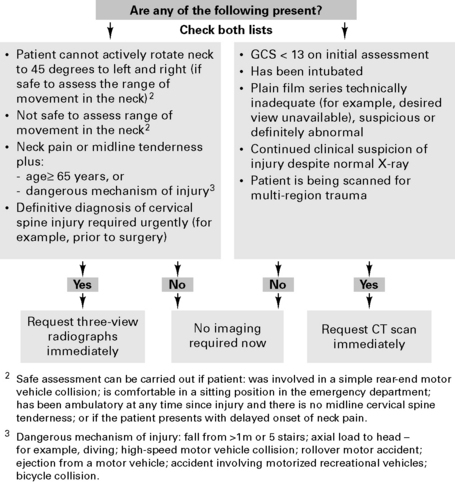

Figure 6.26 Selection of adults and children (age 10+) for imaging of the cervical spine.

(National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence.)

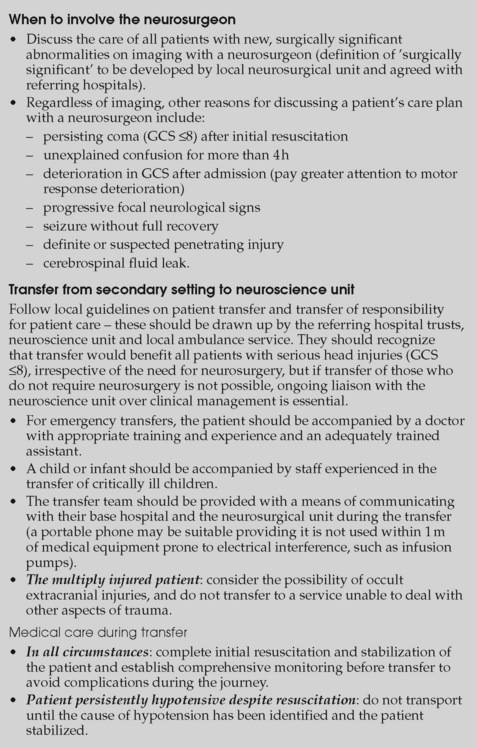

When to involve the neurosurgeon

Transfer from secondary setting to neuroscience unit

| Circumstances | Action |

|---|---|

| Coma – GCS ≤8 (use paediatric scale for children) | Intubate and ventilate immediately |

| Loss of protective laryngeal reflexes | |

| Ventilatory insufficiency: hypoxaemia (Pao2 <13 kPa on oxygen) hypercarbia (Paco2 >6 kPa) |

|

| Spontaneous hyperventilation causing Paco2 <4 kPa | |

| Irregular respirations | |

| Significantly deteriorating conscious level (1 or more points on motor score), even if not coma | Intubate and ventilate before the journey starts |

| Unstable fractures of the facial skeleton | |

| Copious bleeding into mouth | |

| Seizures | |

| Ventilate an intubated patient with muscle relaxation and appropriate short-acting sedation and analgesia | |

| Aim for: | |

| Pao2 >13 kPa | |

| Paco2 4.5–5.0 kPa | |

| If clinical or radiological evidence of raised intracranial pressure, more aggressive hyperventilation is justified | |

| Increase the inspired oxygen concentration if hyperventilation is used | |

| Adult: maintain mean arterial pressure at ≥80 mmHg by infusing fluid and vasopressors as indicated | |

| Child: maintain blood pressure at level appropriate for age | |

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

Recommendations

Anti-seizure prophylaxis

Routine seizure prophylaxis is not indicated in patients >1 week post-injury.

A Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death 2007

Brain Trauma Foundation. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, 2007 www.braintrauma.org/site/PageServer?pagename=Guidelines.

Bratton S.L., Chestnut R.M., Ghajar J., Brain Trauma Foundation; American Association of Neurological Surgeons; Congress of Neurological Surgeons; Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care, AANS/CNS. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(Suppl 1):S37-S44.

Brussel T. Anaesthetic considerations for acute spinal cord injury. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1998;11:467-472.

Dutton R.P. Fluid management for trauma; where are we now? Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:144-147.

Meyer P.-G. Paediatric trauma and resuscitation. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1998;11:285-288.

National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Trauma: who cares?, 2007 http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2007t.htm.

NICE. Head injury: Triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. NICE Clinical Guideline. 2007:56. September www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG56QuickRedGuide.pdf

Nolan J.P., Parr M.J.A. Aspects of resuscitation in trauma. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:226-240.

Royal College of Surgeons of England. Report of the Working Party on the Management of Patients with Major Injuries. London: RCS, 1988.

Shaz B.H., Dente C.J., Harris R.S., et al. Transfusion management of trauma patients. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1760-1768.

Strandvik G.F. Hypertonic saline in critical care: a review of the literature and guidelines for the use in hypotensive states and raised intracranial pressure. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:990-999.

= expected mean

= expected mean