CHAPTER 6 GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT IN CRITICAL ILLNESS

As a reservoir for bacteria and endotoxins, which may translocate into the portal, lymphatic and systemic circulations, producing systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis and multiorgan failure, particularly during periods of altered blood flow. (See Sepsis, p. 326).

As a reservoir for bacteria and endotoxins, which may translocate into the portal, lymphatic and systemic circulations, producing systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis and multiorgan failure, particularly during periods of altered blood flow. (See Sepsis, p. 326). As a reservoir for bacteria which may colonize/infect the respiratory tract. (See Ventilator associated pneumonia, p. 143)

As a reservoir for bacteria which may colonize/infect the respiratory tract. (See Ventilator associated pneumonia, p. 143) The maintenance of gastrointestinal integrity and function is therefore of major importance during critical illness.

The maintenance of gastrointestinal integrity and function is therefore of major importance during critical illness.Manifestations of gastrointestinal tract failure

Failure of the gastrointestinal tract during critical illness may present in a number of ways. These are listed in Box 6.1.

The principle aim of investigation of gastrointestinal dysfunction in the critically ill patients is to exclude serious, remediable, intra-abdominal pathology. In some cases, the combination of history, clinical examination and blood results in the context of the overall clinical picture will suffice. In many cases however, intra-abdominal imaging will be required. Occasionally laparotomy or laparoscopy may be necessary to exclude serious pathology.

DIARRHOEA

As a manifestation of multisystem disorder. For example, generalized tissue hypoxia, tissue oedema and vascular endothelial failure affect the function of all tissues. The gut is no exception to this. These pathological abnormalities are associated with a failure in cellular function and metabolic pathways, which may persist for some time. Consequently, gut failure (either diarrhoea or constipation) is often a characteristic feature of the patient in the intensive care unit.

As a manifestation of multisystem disorder. For example, generalized tissue hypoxia, tissue oedema and vascular endothelial failure affect the function of all tissues. The gut is no exception to this. These pathological abnormalities are associated with a failure in cellular function and metabolic pathways, which may persist for some time. Consequently, gut failure (either diarrhoea or constipation) is often a characteristic feature of the patient in the intensive care unit. As a result of the osmotic load placed on the gut. This may reflect overfeeding, or feeding with a diet whose electrolyte composition is unsuitable for a particular patient.

As a result of the osmotic load placed on the gut. This may reflect overfeeding, or feeding with a diet whose electrolyte composition is unsuitable for a particular patient. As a consequence of infection with a gut pathogen. This is a particular problem in intensive care patients, as the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics suppresses the normal gut flora and allows the emergence and predominance of potentially pathogenic organisms such as Clostridium difficile.

As a consequence of infection with a gut pathogen. This is a particular problem in intensive care patients, as the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics suppresses the normal gut flora and allows the emergence and predominance of potentially pathogenic organisms such as Clostridium difficile.GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Slow bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract may occur, and is a common cause of reduced haemoglobin in the critically ill. Less commonly, but of greater immediate concern is acute massive GIT haemorrhage, which may be life threatening. The source is usually the upper GIT. Common causes are listed in Box 6.2. Bleeding of this sort can result in haematemesis, melaena or even frank rectal blood loss. Lower GIT bleeding is less common, but may still be life threatening.

Box 6.2 Causes of upper gastrointestinal tract haemorrhage

Gastric erosion and ulceration

Management

Large-bore vascular access is obtained and resuscitation of hypovolaemia commenced. In massive bleeds full haemodynamic monitoring, including arterial line, CVP or some other measure of volume status, are valuable.

Large-bore vascular access is obtained and resuscitation of hypovolaemia commenced. In massive bleeds full haemodynamic monitoring, including arterial line, CVP or some other measure of volume status, are valuable. Analgesics and anxiolytics are used judiciously in conscious patients. Massive bleeds, however, frequently necessitate intubation and ventilation.

Analgesics and anxiolytics are used judiciously in conscious patients. Massive bleeds, however, frequently necessitate intubation and ventilation.ABDOMINAL COMPARTMENT SYNDROME

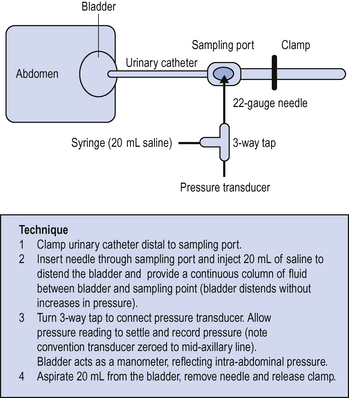

The presence of blood, free fluid or gas in the abdominal cavity, splanchnic and tissue oedema and organomegally can lead to a progressive increase in the intra-abdominal pressure and to decreased splanchnic perfusion. This may result in gut, renal and liver hypoperfusion with associated clinical features. If suspected, intra-abdominal pressure can be measured via an indwelling urinary catheter (Fig. 6.1).

Normal intra-abdominal pressure is less than 15–20 mmHg. Intra-abdominal pressures above 20 mmHg with evidence of end organ dysfunction are suggestive of abdominal compartment syndrome. Decompression of the abdomen may be required. Seek surgical advice. Once opened, it may be impossible to close the abdomen at first laparotomy. The abdomen may be left ‘open’ under sterile plastic coverings for later closure when the swelling has subsided.

HEPATIC FAILURE

Liver failure is defined as hyperacute where the onset of encephalopathy occurs within 7 days of the onset of jaundice, acute where the interval is 7–28 days, and subacute where it is between 28 days and 6 months. Longer intervals represent chronic liver failure. The term fulminant liver failure refers to an earlier classification where encephalopathy occurs within 8 weeks of the onset of jaundice. It thus encompasses acute and hyperacute liver failure.

Clinical features

Hypoglycaemia is common and develops any time in the first few days of the condition. It gradually resolves as the liver failure improves. Acid – base homeostasis is altered and either alkalosis or acidosis may complicate this. A metabolic acidosis is the more sinister. Concurrently with the development of the metabolic derangement, conscious level may become impaired. Encephalopathy is graded as in Table 6.1.

| Grade 0 | Normal |

| Grade 1 | Mild confusion (may not be immediately evident) |

| Grade 2 | Drowsiness |

| Grade 3 | Severe drowsiness, inappropriate words/phrases, grinding teeth |

| Grade 4 | Unrousable |

True‘infective’ sepsis may occur. A rising WCC, falling platelet count, a PT whose recovery becomes arrested or a worsening acidosis should all be regarded as suspicious.

Management

The development of grade III–IV encephalopathy or the onset of SIRS is an indication for tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. This protects the airway, reduces the work of breathing and protects against the risk of secondary hypoxic damage.

The development of grade III–IV encephalopathy or the onset of SIRS is an indication for tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. This protects the airway, reduces the work of breathing and protects against the risk of secondary hypoxic damage. Fluid and haemodynamic management is guided by invasive monitoring. Maintain adequate filling to ensure optimal CO while avoiding the risk of interstitial oedema of the lung, brain and gut.

Fluid and haemodynamic management is guided by invasive monitoring. Maintain adequate filling to ensure optimal CO while avoiding the risk of interstitial oedema of the lung, brain and gut. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) is used to keep the mean arterial pressure above 70–80 mmHg and the CPP >50 mmHg (see below).

Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) is used to keep the mean arterial pressure above 70–80 mmHg and the CPP >50 mmHg (see below). Renal failure can make fluid balance difficult. Continuous renal replacement therapy is frequently necessary, but is often associated with transient haemodynamic instability and ICP surges.

Renal failure can make fluid balance difficult. Continuous renal replacement therapy is frequently necessary, but is often associated with transient haemodynamic instability and ICP surges. All patients should receive continuous N-acetylcysteine infusion (100 mg/kg per 24 h). This has been shown to improve outcome in fulminant liver failure irrespective of aetiology, even when instituted relatively late in the disease process.

All patients should receive continuous N-acetylcysteine infusion (100 mg/kg per 24 h). This has been shown to improve outcome in fulminant liver failure irrespective of aetiology, even when instituted relatively late in the disease process.Metabolic issues

Hypoglycaemia is common. All infusions should be made up in dextrose solutions (5–20%), and dextrose (5–50%) infused to maintain a normal blood sugar.

Hypoglycaemia is common. All infusions should be made up in dextrose solutions (5–20%), and dextrose (5–50%) infused to maintain a normal blood sugar. Nitrogenous feeds are avoided (no TPN or nasogastric feed should be administered until metabolic resolution of acute liver failure).

Nitrogenous feeds are avoided (no TPN or nasogastric feed should be administered until metabolic resolution of acute liver failure). Sodium and potassium are maintained within the normal range; this may involve judicious use of potassium infusions at 10–40 mmol/h.

Sodium and potassium are maintained within the normal range; this may involve judicious use of potassium infusions at 10–40 mmol/h. The liver is unable to metabolize citrate used as an anticoagulant in blood products. Consequently, persisting citrate chelates calcium, and may drastically reduce ionized calcium levels. Calcium chloride 10 mmol may be given by slow bolus to maintain the ionized calcium to above 0.8 mmol/L.

The liver is unable to metabolize citrate used as an anticoagulant in blood products. Consequently, persisting citrate chelates calcium, and may drastically reduce ionized calcium levels. Calcium chloride 10 mmol may be given by slow bolus to maintain the ionized calcium to above 0.8 mmol/L. Metabolic acidosis is a useful prognostic indicator and is in any case best left untreated on theoretical grounds. The exception to this is where a severe acidosis is associated with haemodynamic instability. It is acceptable to correct the pH slowly to 7.2 if this improves the haemodynamic status. Rapid correction of acidosis with boluses of sodium bicarbonate should be avoided. The use of sodium bicarbonate can result in a transient dramatic elevation in the carbon dioxide tension, with consequent cerebral vasodilatation and a surge in ICP.

Metabolic acidosis is a useful prognostic indicator and is in any case best left untreated on theoretical grounds. The exception to this is where a severe acidosis is associated with haemodynamic instability. It is acceptable to correct the pH slowly to 7.2 if this improves the haemodynamic status. Rapid correction of acidosis with boluses of sodium bicarbonate should be avoided. The use of sodium bicarbonate can result in a transient dramatic elevation in the carbon dioxide tension, with consequent cerebral vasodilatation and a surge in ICP.Control of ICP

Keep physiotherapy, tracheal suctioning and turning to a minimum until the risk of ICP surges resolves (usually 5 days after the onset of grade IV encephalopathy).

Keep physiotherapy, tracheal suctioning and turning to a minimum until the risk of ICP surges resolves (usually 5 days after the onset of grade IV encephalopathy). Primary surges in ICP (often followed by a reflex rise in arterial pressure) are treated acutely by hyperventilation. The response to hyperventilation is not maintained, so it should be discontinued as soon as a fall in ICP is seen. Mannitol 20% 100 ml is used to sustain the reduction in ICP and also where the baseline ICP remains above 25 mmHg. Other hyperosmolar therapies, for example hyperosmolar saline are also of value. The use of these agents should be discussed with your regional centre.

Primary surges in ICP (often followed by a reflex rise in arterial pressure) are treated acutely by hyperventilation. The response to hyperventilation is not maintained, so it should be discontinued as soon as a fall in ICP is seen. Mannitol 20% 100 ml is used to sustain the reduction in ICP and also where the baseline ICP remains above 25 mmHg. Other hyperosmolar therapies, for example hyperosmolar saline are also of value. The use of these agents should be discussed with your regional centre.Prognosis

Without transplantation, the prognosis is poorest in the subacute group and best in the hyperacute group. Within this group, the prognosis is poorer in those at the extremes of age, those with non-A, non-B hepatitis and drug dyscrasia. The overall mortality in patients with grade IV encephalopathy is 70%. With liver transplantation (i.e. in those patients at the highest risk of death with optimal medical management), the 1-year mortality is between 30 and 50%.

ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Inflammation of the pancreas and autodigestion may be precipitated by a number of triggers, some of which are listed in Box 6.3. The commonest causes are alcohol and biliary obstruction. Frequently no cause can be identified.

Box 6.3 Common causes of pancreatitis

Biliary obstruction (gallstones) / ERCP

Investigations

Localized posterior perforations of duodenum or stomach may be difficult to distinguish. Chest and abdominal plain films should confirm the absence of free gas or pneumonia, and may show calcium deposition. In severe cases the typical radiographic features of ARDS may be present. Plain film and ultrasound may confirm the presence of gallstones or other underlying biliary lesion. Blood glucose and arterial gases should be closely monitored. As the condition progresses, serial CT scanning is valuable to monitor pancreatic viability and to diagnose pancreatic cysts and pseudocysts.

Acute hepatic failure carries a high mortality and treatment options include transplantation. Early discussion with a specialist centre is therefore mandatory.

Acute hepatic failure carries a high mortality and treatment options include transplantation. Early discussion with a specialist centre is therefore mandatory.

The prothrombin time (PT) is one of the key prognostic factors determining whether the optimal treatment of acute liver failure is likely to be medical or surgical. Therefore, do not treat coagulopathy (by, for example, giving fresh frozen plasma) except in cases of life threatening aemorrhage.

The prothrombin time (PT) is one of the key prognostic factors determining whether the optimal treatment of acute liver failure is likely to be medical or surgical. Therefore, do not treat coagulopathy (by, for example, giving fresh frozen plasma) except in cases of life threatening aemorrhage.