Gastrointestinal System

Nontumorous Diseases of the Small and Large Intestines

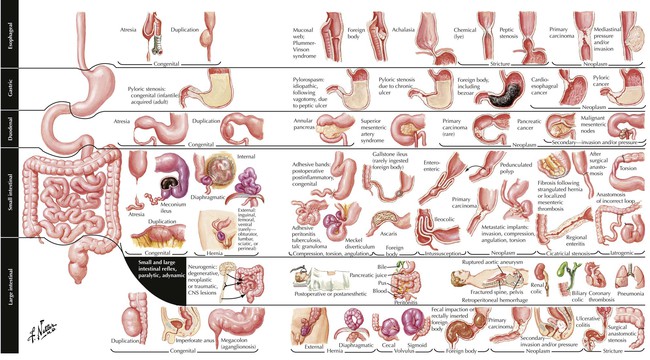

Congenital disorders of the intestines are uncommon and are discussed in Table 4-1 and malabsorption syndromes in Table 4-4.

TABLE 4-1

DEVELOPMENTAL INTESTINAL DISEASES

| Disease | Features |

| Small intestine | |

| Atresia | Complete occlusion of intestinal lumen secondary to intraluminal diaphragm or disconnected blind ends (occurs in fetuses of mothers with polyhydramnios) |

| Stenosis | Partial occlusion (stricture) of the intestinal lumen secondary to incomplete intraluminal diaphragm, external adhesions (e.g., secondary to [transient] volvulus) |

| Duplications | Tubular or cystic structures (enteric cysts) that may communicate with the intestinal lumen (most common in ilium; may contain gastric mucosa and cause peptic ulcer similar to Meckel diverticulum) |

| Meckel diverticulum | Partial persistence of the vitelline duct, 60–100 cm before the ileocecal valve, with all layers of intestinal or gastric mucosa |

| Large intestine | |

| Malrotation | Abnormal positioning of colon in abdominal cavity (e.g., cecum in left upper quadrant); may give rise to volvulus |

| Hirschsprung disease | Congenital megacolon secondary to aganglionic segment (lack of Auerbach and Meissner plexus preferentially in sigmoid colon and rectum) |

Tumors of the Small and Large Intestines

TABLE 4-2

HISTOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF GASTRITIS

| Type of Gastritis | Histologic Features | Course |

| Common acute gastritis | Mucosal edema Neutrophilic infiltration with or without erosions Petechiae with or without mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltration Epithelial regeneration in neck region of glands |

Usually transient |

| Eosinophilic gastritis | Eosinophilic infiltrates of all layers, frequently with muscular hypertrophy | Incidental or recurrent (may be related to allergies or ingestion of chemical irritants) |

| Chronic type B gastritis (more common) |

Superficial lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate Neutrophils if erosive, with or without lymph follicles Colonization by Helicobacter pylori Elongation of glandular necks with epithelial regeneration Intestinal metaplasia in late phase |

Chronic persistent or recurrent May predispose to carcinoma or lymphoma |

| Chronic type A gastritis | Patchy lymphocytic infiltrate with invasion of crypt epithelia and epithelial degeneration Loss of acidophilic cells Intestinal metaplasia |

Chronic aggressive Decreased vitamin B12 resorption may predispose to cancer* |

TABLE 4-3

PATHOGENESIS OF CARCINOMA OF THE STOMACH

| Factors | Prevalence and Examples |

| Nutritional factors | Apparently account for geographic variations in cancer incidence: large amounts of smoked fish, pickled vegetables, highly salted foods; diets low in fruits and vegetables (i.e., in protective antioxidants) Identified carcinogens: nitrosamines, benzpyrene |

| Infections | Chronic Helicobacter pylori infection as cofactor (see above) |

| Genetic factors | Approximately half of cancer patients possess blood group A No clearcut genetic traits identified Changes in tumor suppressor gene activity (e.g., p53), germline mutations, and genetic mismatch repair similar to cancer of the colon (see there) |

| Other factors | Low socioeconomic status (probably related to nutritional factors and infection) |

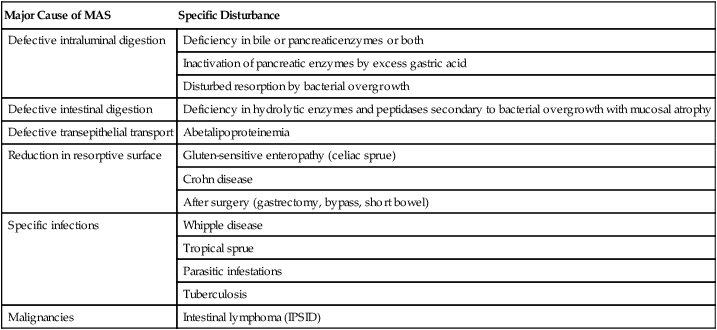

TABLE 4-4

PATHOGENESIS OF MALABSORPTION SYNDROMES*

| Major Cause of MAS | Specific Disturbance |

| Defective intraluminal digestion | Deficiency in bile or pancreaticenzymes or both |

| Inactivation of pancreatic enzymes by excess gastric acid | |

| Disturbed resorption by bacterial overgrowth | |

| Defective intestinal digestion | Deficiency in hydrolytic enzymes and peptidases secondary to bacterial overgrowth with mucosal atrophy |

| Defective transepithelial transport | Abetalipoproteinemia |

| Reduction in resorptive surface | Gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac sprue) |

| Crohn disease | |

| After surgery (gastrectomy, bypass, short bowel) | |

| Specific infections | Whipple disease |

| Tropical sprue | |

| Parasitic infestations | |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Malignancies | Intestinal lymphoma (IPSID) |

*IPSID indicates immunoproliferative small intestinal disease; MAS, malabsorption syndrome.

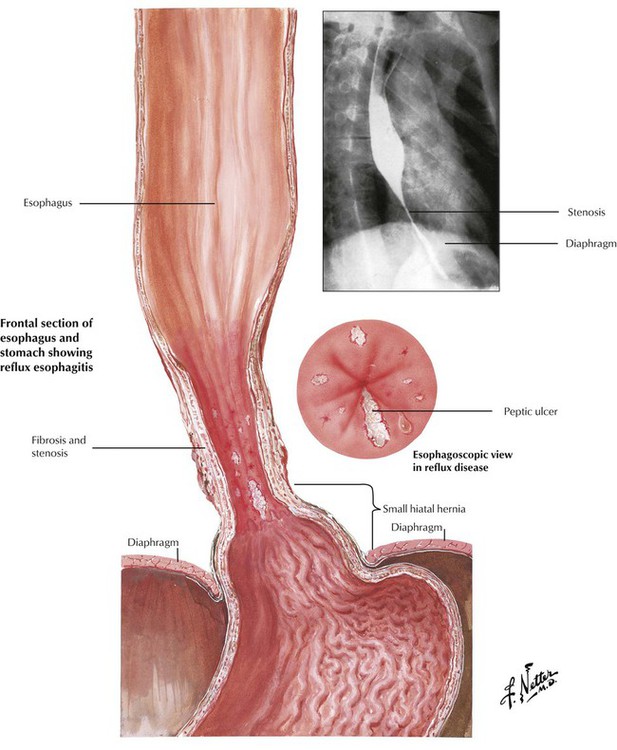

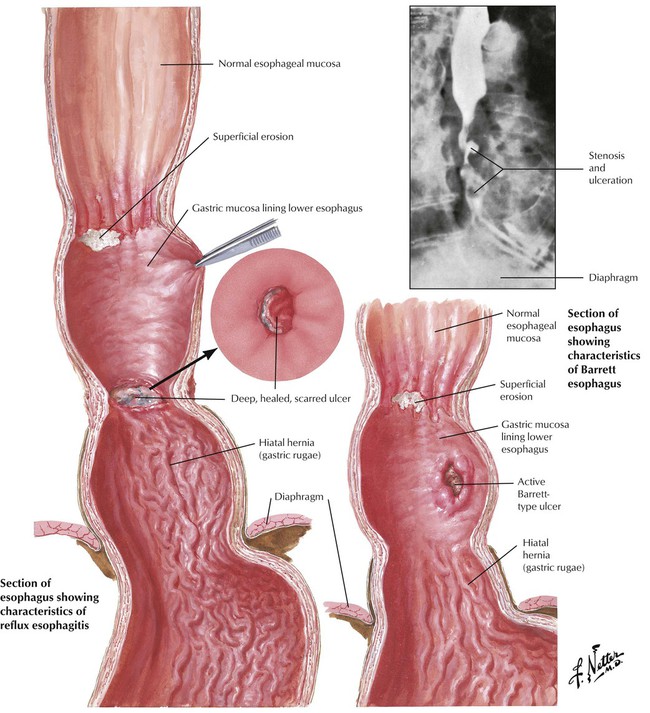

Esophagitis, which affects up to 20% of people in developed countries, is usually caused by gastric reflux (reflux esophagitis). Reflux esophagitis follows a “chemical” irritation by gastric fluids containing acid and pepsin (peptic esophagitis), which is secondary to improper closure of the lower esophageal sphincter. The tonus of the lower esophageal sphincter may be decreased by hiatal hernia of the stomach; voluminous intake of fatty foods; increased chocolate, alcohol, or nicotine consumption; hormonal factors (estrogen therapy, pregnancy); or treatment with central nervous system (CNS) depressants such as diazepam or opiates. Pathologically, acute reflux esophagitis shows hyperemia and mild degenerative changes such as ballooning of epithelial cells, occasional mild superficial erosion, and occasionally eosinophilic (rarely neutrophilic) infiltration. Chronic disease results in fibrosis and stenosis.

Chronic reflux esophagitis is classified into stages of severity. Stage I is characterized by epithelial hyperplasia and keratosis (clinical finding: leukoplakia) with sparse submucosal lymphocytic infiltrate. Stage II resembles stage I, with the addition of superficial erosion and neutrophilic infiltration. Stage III resembles stage II, with epithelial ulceration and more pronounced epithelial regeneration (elongated epithelial papillae). Complications of chronic reflux esophagitis include fibrous scarring and stenosis, mucosal metaplasia, and cancer. Barrett esophagus (BE) is the focal replacement of stratified squamous epithelium by metaplastic columnar epithelium with goblet cells. BE appears grossly as velvety, pink islands of mucosa in the lower third of the esophagus. Besides the intestinal-type mucosa, gastric mucosal elements (cardia- or fundus-type glands, including parietal and chief cells) are frequent. BE is associated with a greatly increased incidence of adenocarcinoma.

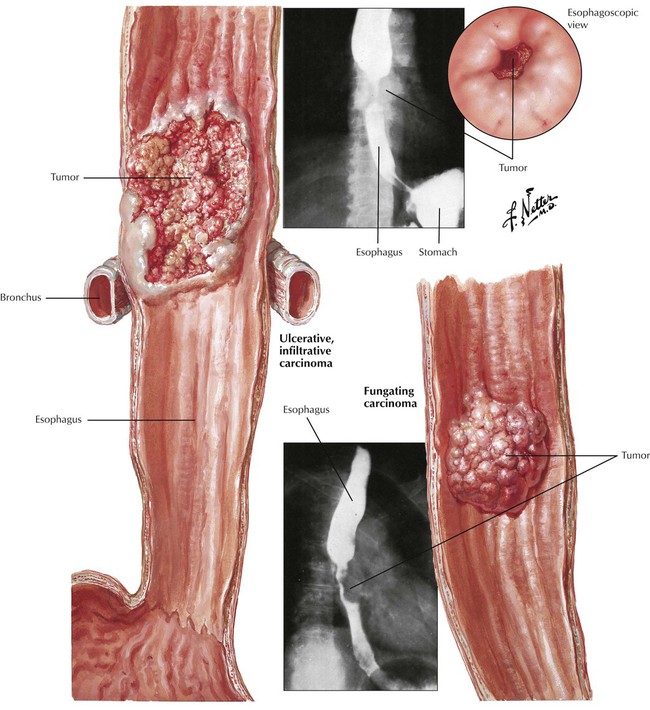

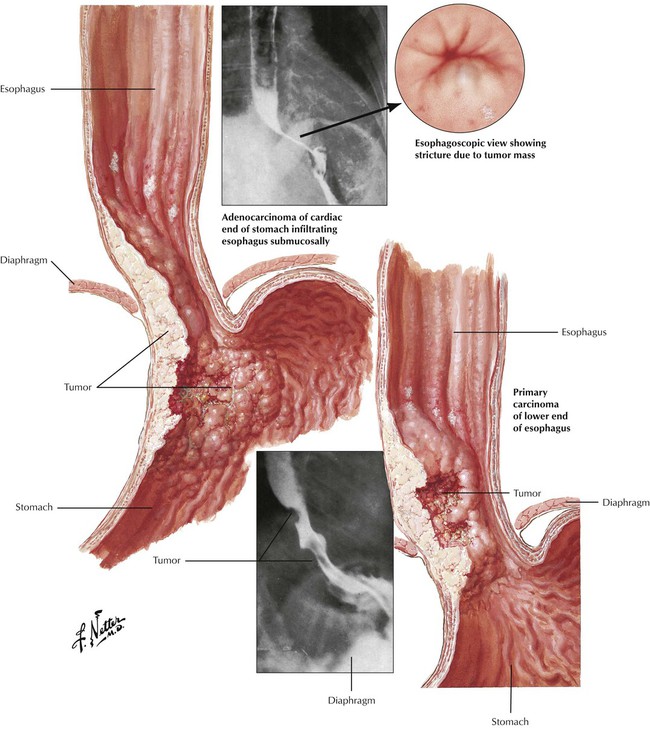

Malignant neoplasms of the esophagus account for up to 2% of cancer deaths in the United States annually. Certain ill-defined genetic predispositions, exposure to food carcinogens (e.g., nitrosamines), tobacco smoke, chronic alcoholism, and chronic esophagitis (especially with BE) seem to be important pathogenetic factors. Loss of p53 tumor suppressor gene function is one of the most frequently observed molecular changes in esophageal cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma usually impresses as a plaquelike or fungating white lesion in the upper or medial part of the esophagus. The tumor infiltrates the esophageal wall deeply, penetrates into the mediastinum, and spreads via lymphatic channels. Invasion of the bronchial tree may occur with fistulation. Severe dysphagia and anorexia cause pronounced cachexia. The 5-year survival rate is 10% for patients with squamous cell carcinoma.

Adenocarcinomas, which account for 25% of cases of esophageal cancer, are pinkish elevated or ulcerative lesions in the lower third of the esophagus. Ulcerative lesions may appear as direct extensions of lesions in the gastric cardia. Onset is usually insidious, and tumors develop slowly. Dysphagia, weight loss, anorexia, and fatigue are the most common symptoms. Surgical removal of the tumor is frequently incomplete because of the early and extensive local metastases within the gastroesophageal wall and into the mediastinum. Even with surgery, the 5-year survival rate is 20% for patients with adenocarcinoma.

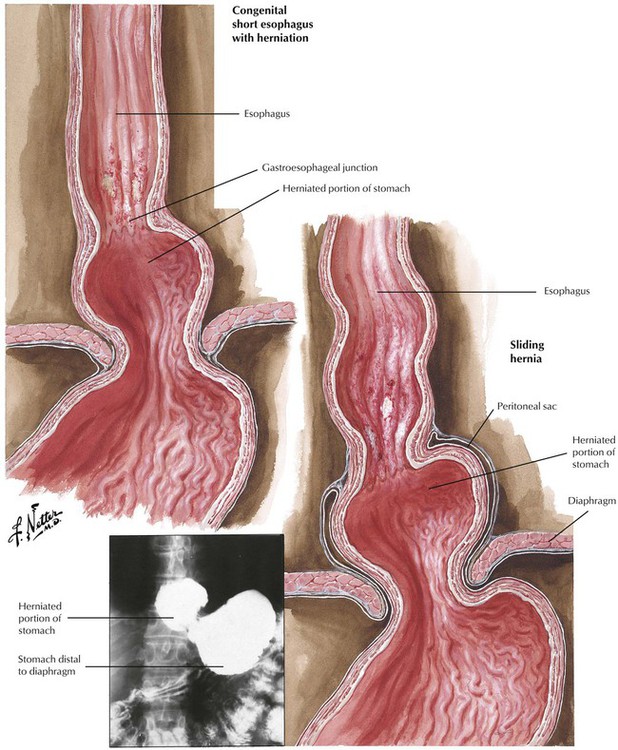

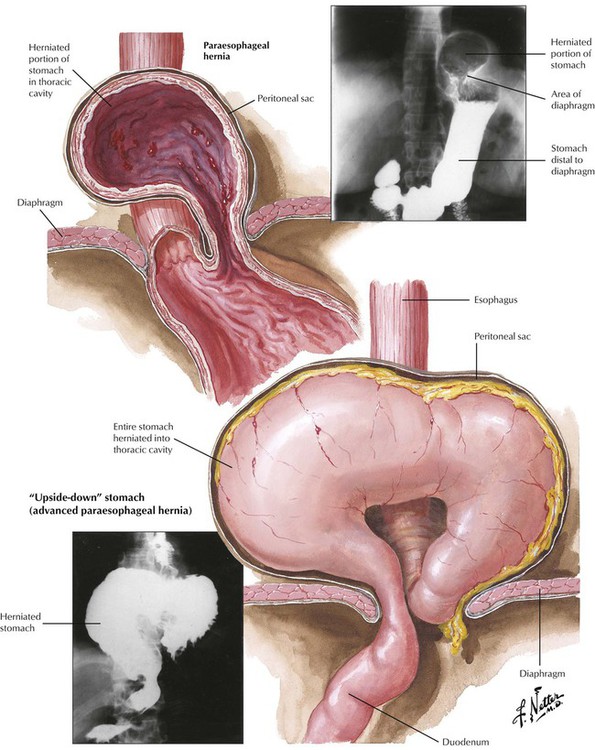

There are 2 types of gastric herniation (hiatal hernia) into the thoracic space: sliding (axial) hernias and paraesophageal (nonaxial) hernias. Sliding hernia constitutes approximately 95% of hiatal hernias. Systematic radiologic studies reveal sliding hernias in up to 20% of the population, only approximately half of which are symptomatic. Symptoms consist of heartburn and regurgitation of gastric contents and subsequent reflux esophagitis. Paraesophageal hernia causes strangulation of parts or all of the stomach incarcerated above the diaphragm. Surgical correction should be considered for both types of hernia.

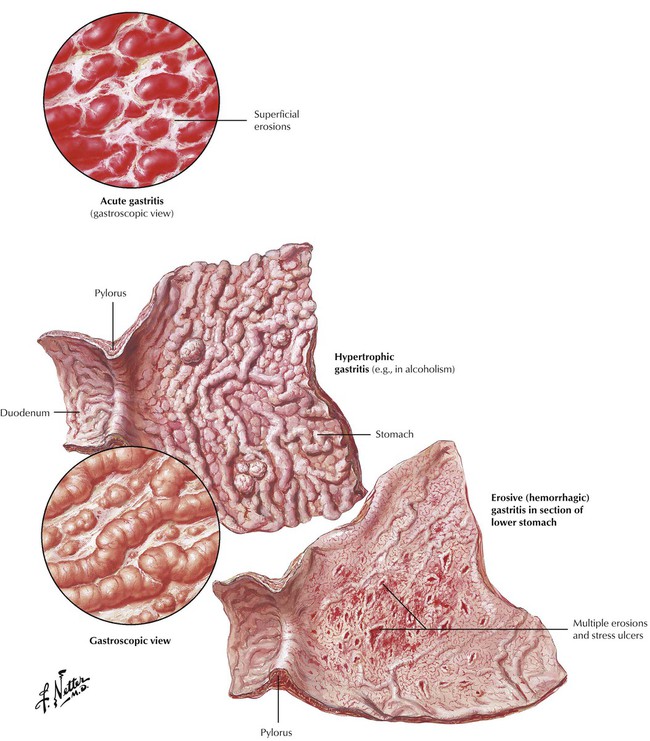

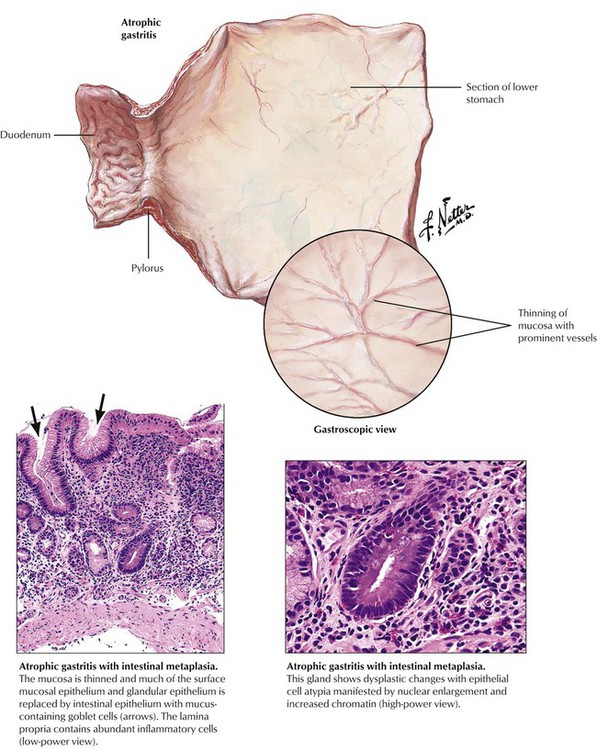

Gastritis is the most common cause of upper abdominal pain in adults. Gastroscopy differentiates the gross features of acute gastritis, erosive gastritis, hypertrophic gastritis, and chronic (atrophic) gastritis. Biopsy and pathologic investigation offer a more exact classification of pathogenesis and prognosis (Table 4-2). Acute gastritis is usually caused by chemical irritation by alcohol, cigarette smoke, or drugs (e.g., aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, chemotherapeutics), uremia, or suicidal ingestion of acids or alkali. Severe stress can cause acute gastritis with erosion and ulceration (“stress ulcer”). Systemic infections, shock involving the stomach, loss of pyloric function (e.g., after surgery) or duodenobiliary reflux can initiate acute gastritis. Infection with Helicobacter pylori accounts for 50% to 80% of cases of chronic type B gastritis. Chronic type A gastritis, an autoimmune gastritis, may occur alone or accompany other autoimmune disorders (thyroiditis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, Addison disease).

The pathologic term atrophic gastritis is reserved for chronic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia (i.e., specific crypts of the gastric corpus are replaced by intestinal glands with goblet cells). Glandular necks are markedly elongated with extended epithelial regeneration involving surface epithelia and increasing amounts of dysplastic glands and epithelial atypia. Patients with atrophic gastritis have the highest risk of developing gastric cancer. Table 4-2 summarizes the histologic features and the courses of various types of gastritis.

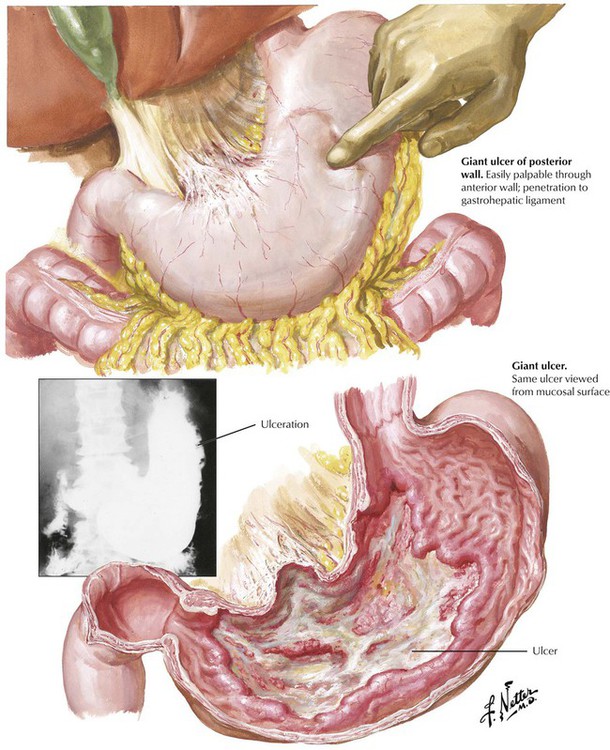

Peptic ulcers (PUs) of the stomach or duodenum represent approximately 98% of ulcerations in this region. PUs are usually chronic, whereas the less common “stress ulcers,” which may accompany extensive burns, severe trauma, or other situations of excessive stress or the administration of certain drugs (corticosteroids), are acute. The pathogenesis of PU includes excessive action of gastric acid and pepsin, reduced mucosal defense mechanisms (e.g., reduced mucus production, reduced epithelial regeneration such as in tobacco smoking), and, frequently, infection with H pylori. PUs require treatment because of the possibility of complications, including acute or chronic hemorrhage and anemia, perforation, chronic scarring and stenosis (e.g., in pyloric or postpyloric ulcers), penetration into adjacent organs (e.g., into the pancreas with subsequent pancreatitis), and development of carcinoma within the regenerating mucosa adjacent to the ulcer.

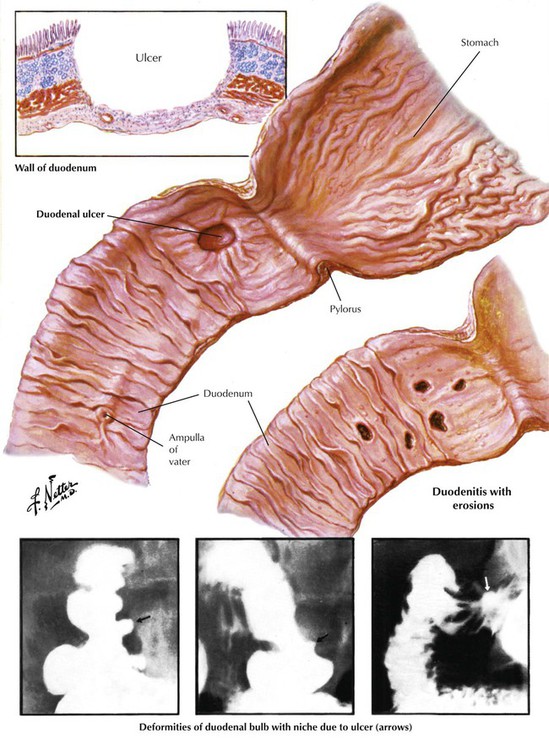

Duodenal ulcers are usually located in the anterior or posterior wall of the bulbus and occur secondary to hyperacidification. The mucosa in this area is especially sensitive to acid juices. The pathogenesis and complications of duodenal ulcers resemble those of stomach ulcers, although malignant transformation to cancer is rare.

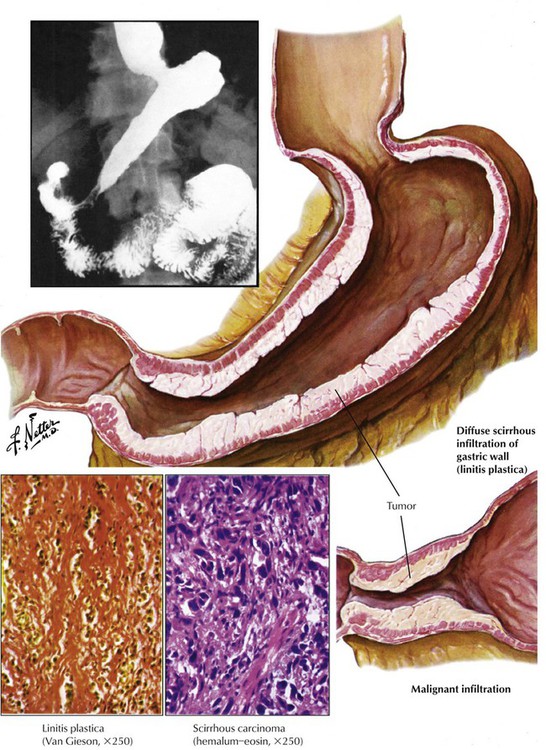

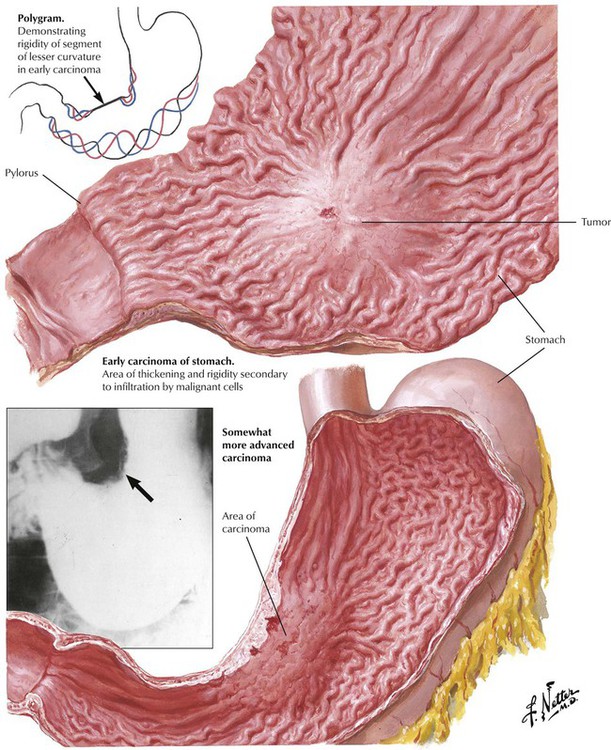

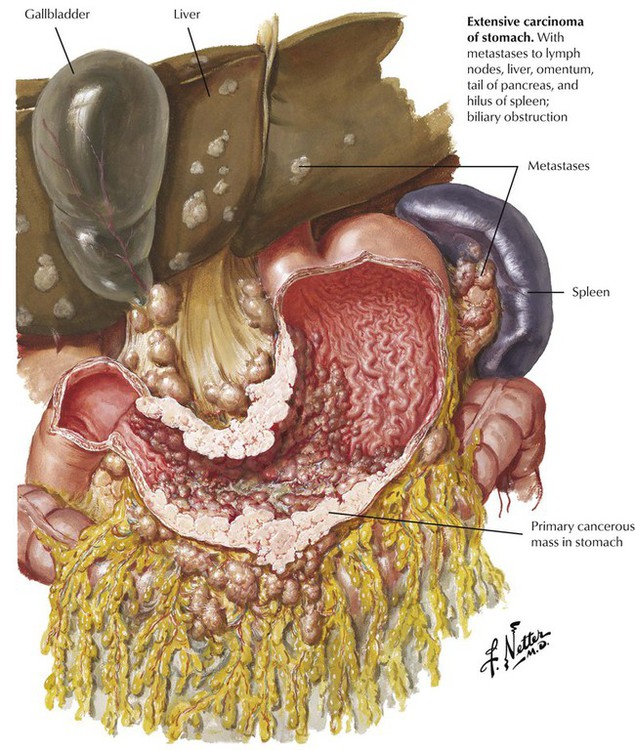

Carcinomas of the stomach are among the most common tumors in the Western world and Japan. Approximately 50% develop in the antrum or pyloric region, approximately 25% develop in the corpus, and 25% develop in the fundus. Most tumors are located in the lesser curvature. Their gross features vary from mucosal flattening and thickening with erosions to diffuse thickening of the gastric wall (linitis plastica), to large ulcers or polypoid-fungating masses. Stomach carcinomas are classified as type I: protruding nodular or polypoid lesion; type II: slightly elevated or depressed flat lesion; and type III: excavated or ulcerated lesion. There are 2 main histologic types of classic carcinoma of the stomach: the intestinal type with tubular glands, which simulates atypical intestinal mucosa, and the diffuse type with extensive mucus production by signet ring cells (signet ring cell carcinoma and linitis plastica including also less mature cells). Polypoid adenocarcinomas are found in the cardia and in rare preexistent adenomas.

Early gastric cancer is a pathologic term for a tumor confined to mucosa or submucosa. It is generally asymptomatic and is detected only by chance. Patients with this tumor have a 10-year survival rate of 95% after surgical intervention; patients with other stomach tumors have a combined survival rate of only 20%. Advanced gastric cancer also may be clinically occult except for undefined abdominal discomfort and weight loss. Large tumors in the prepyloric area may cause obstruction. Acute massive bleeding, even in ulcerated tumors, is uncommon, whereas chronic bleeding with significant anemia is frequently observed.

All gastric carcinomas spread by direct extension to nearby organs or metastasize via lymphatic channels and the bloodstream. Even in early cancer, there is a 5% risk of regional lymphatic metastases at the time of initial tumor diagnosis. The most common sites of metastasis are lymph nodes at the lesser or greater curvature of the stomach, in the subpyloric region, and in the porta hepatis. More distant metastases involve the left supraclavicular lymph nodes (Virchow node), the lungs, the bone marrow, and the ovaries (Krukenberg tumor). The etiology and pathogenesis of gastric cancer are reviewed in Table 4-3.

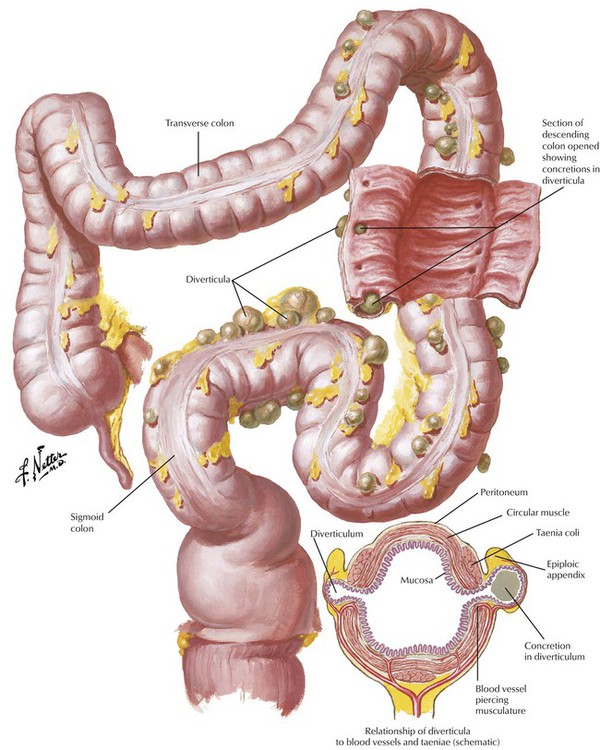

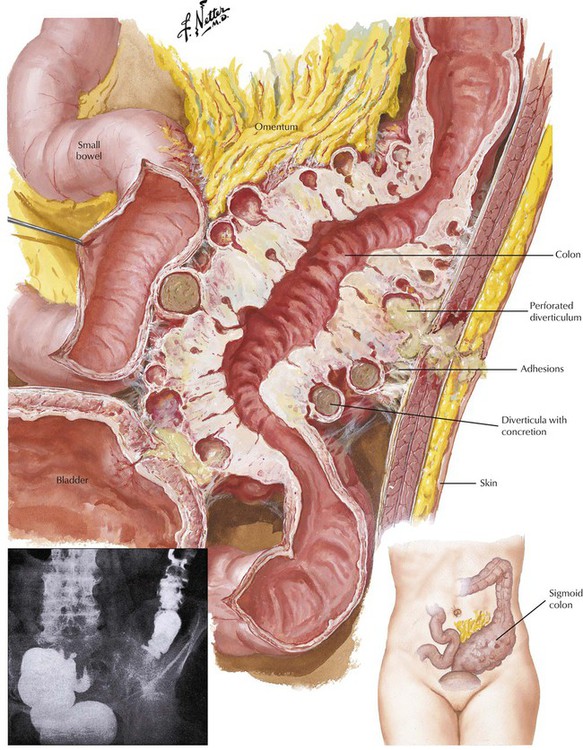

Diverticulosis of the colon is a herniation of the colonic mucosa and submucosa through the intestinal muscular wall, with cystic expansion in the adventitial tissue. In Western countries, it affects up to half of persons older than 60 years. Diverticulosis is found most often in the sigmoid colon, although it may affect any part of the intestine. Diverticula, which develop at sites of weakness in the muscle wall of the intestine (sites of vascular and nerve penetrations), are secondary to increased colon pressure (enhanced peristaltic contractions) induced by a low-fiber diet. Gross bleeding or subclinical chronic bleeding from the diverticula may occur, especially in elderly persons. Stasis of feces in the diverticula is followed by recurrent inflammation (diverticulitis) with adhesions, occasional intestinal distortion, and obstruction. Inflamed diverticula can perforate and induce life-threatening fecal peritonitis. In advanced cases, surgical correction may be necessary.

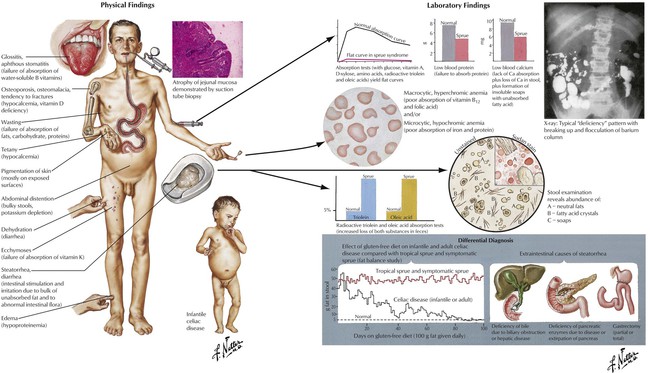

Malabsorption syndrome (MAS) is characterized by the failure of the intestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients from food. It results from insufficient digestion (luminal and intestinal phases) or transepithelial transport. MAS is a heterogeneous syndrome that can result from a variety of disorders (Table 4-4). Most commonly, MAS results from chronic pancreatitis, Crohn disease, or celiac sprue. Histologically, celiac sprue appears as villous atrophy in the upper small intestine with elongation and arborization of glandular crypts, atrophic and regenerative epithelial changes, mild neutrophilic infiltration, and an increase in immunoglobulin (Ig) G– or IgM-containing plasma cells or both. Whipple disease, in which the intestinal mucosa contains large accumulations of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction–positive macrophages packed with rod-shaped bacilli, is also associated with clinical malabsorption. The presentation of MAS is determined by the deficits in nonabsorbed nutrients. General symptoms of weight loss, anorexia, and abdominal distention are combined with specific deficiencies of nutrients such as vitamin B12 or folic acid (megaloblastic anemia), vitamin K deficiency (bleeding with petechiae), vitamin D and calcium deficiency (osteomalacia, tetany), vitamin A deficiency (hyperkeratoses and dermatitis), protein deficiencies (edema, malnutrition), and zinc deficiency (dermatitis and immune defects). Stools are bulky, yellowish gray, and greasy. Treatment, clinical course, and prognosis are based on the primary disorder.

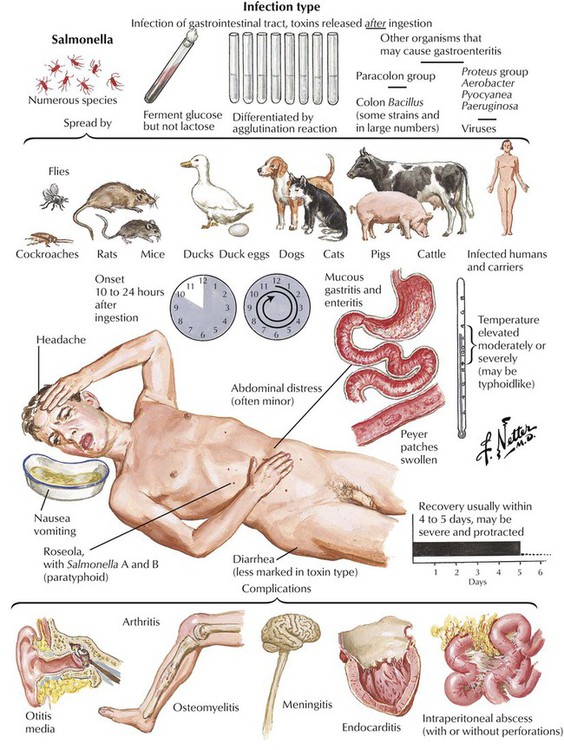

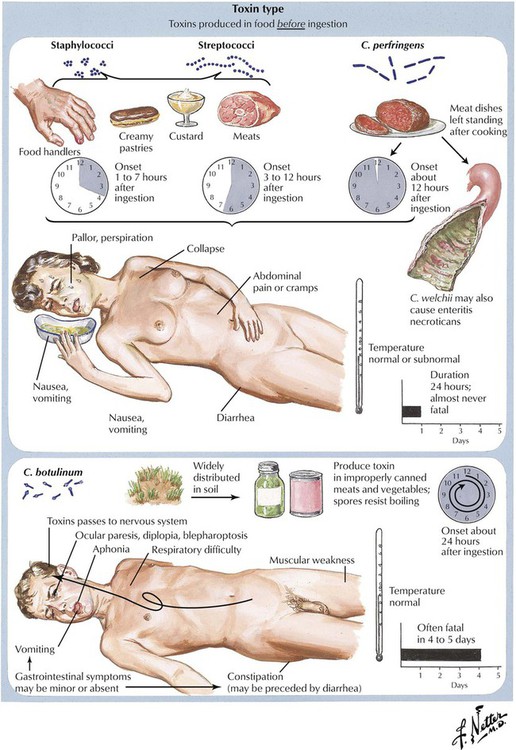

Food poisoning is an acute diarrheal GI disease that follows the ingestion of contaminated food. It is caused by colonization of the GI tract with pathogenic organisms released after ingestion of contaminated food (infection type), by toxins produced in food before ingestion (toxin type), or by a combination of both. The infection type affects the small intestine preferentially. Most cases of food poisoning resolve in 1 to 5 days, except for those caused by Clostridium botulinum, which is frequently lethal within 5 days. Infection with enterotoxic E. coli and with Salmonella species (especially in older persons) may cause more frequent deaths. Salmonella organisms may persist in asymptomatic carriers after resolution of the acute enteric disease and become the source of future food poisoning cases.

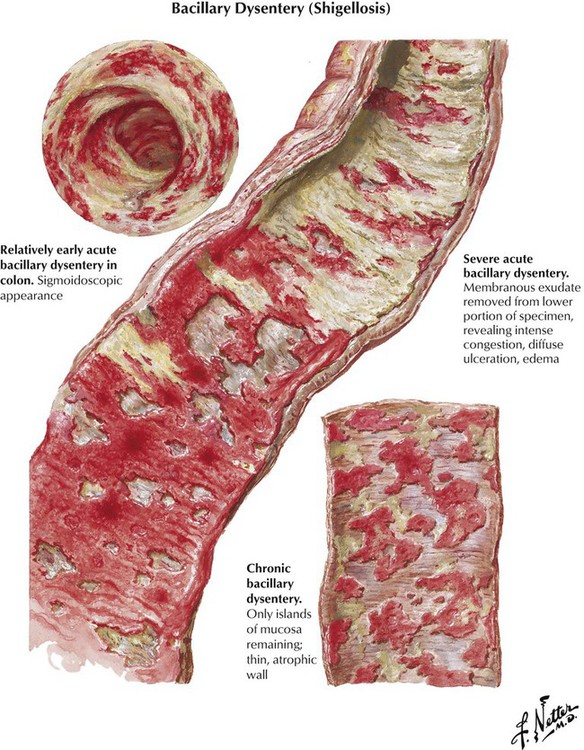

Shigellosis, an enterocolitis, is caused by infection with Shigella organisms. These organisms produce either potent exotoxins, which cause acute disease (S. kruse) or endotoxins, which cause insidious onset of chronic disease (S. flexner, S. sonnei). The incubation period is usually short (2–4 days). Pathologic lesions in the large intestine consist of irregular patchy pseudomembranous colitis (i.e., fibrinopurulent inflammation with superficial erosions and eventual ulceration) within a markedly hyperemic mucosa and increased mucus production. Clinical symptoms include frequent bowel movements and diarrhea, colicky pains, and, eventually, bloody stools with mucoid streaks. Prognosis is good when fever and fluid loss are promptly controlled and specific antibiotic/sulfonamide therapy is administered. Occasionally, fulminating toxic and lethal conditions may arise in small children and in the elderly.

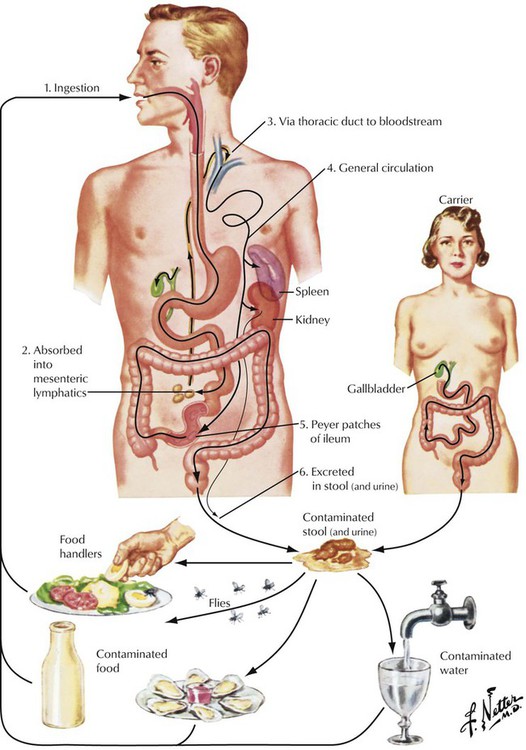

Typhoid fever (TF), which is prevalent in underdeveloped countries but rare in the Western world, is caused by Salmonella typhi Eberthi. The common source of infection is bacteria from contaminated meat, milk, or eggs. A brief transient febrile illness with abdominal discomfort ensues, during which the organisms settle in macrophages and lymphoid tissues with respective stimulation of the immune system. The cyclic infectious disease phase of TF starts after a latent period of 10 days to 3 weeks, during which bacteria spread via lymphatics and blood and immunity is established. Bacteria accumulate in intestinal lymphatic tissues, especially in the Peyer patches, which become inflamed and ulcerated. Transient pseudomembranes shaped like Peyer patches cover these ulcers. TF evolves into a systemic infection through the hematogenous spread of organisms. Immunologically induced granulomas develop at the sites of bacterial colonization such as in the spleen, the liver, the bone marrow, and the spine, and hepatosplenomegaly ensues.

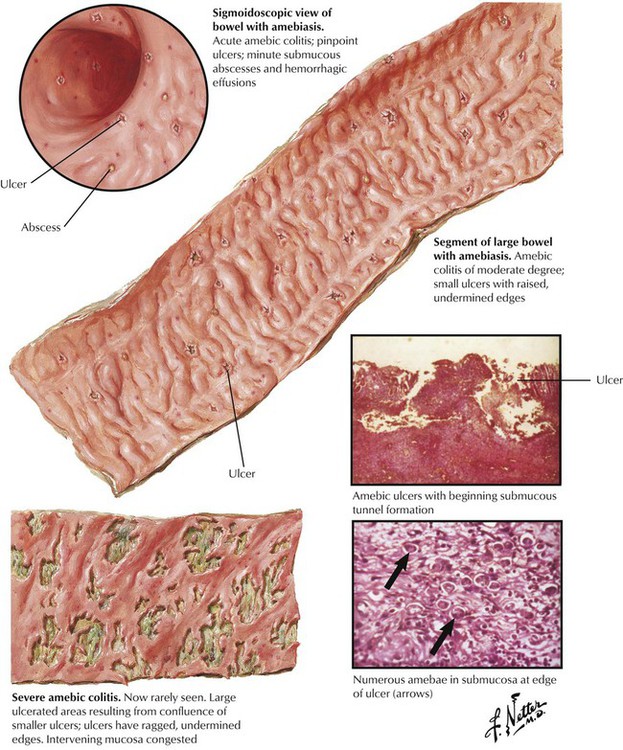

Protozoal infection by Entamoeba histolytica (amebiasis) causes up to 10% of human intestinal infections. Ingestion of cysts in food or drink contaminated by human fecal materials, including manure-fertilized vegetables, causes the infection. Flies and other insects that feed on human feces transfer the protozoa to foods. Amebiasis is marked by ulcerating proctosigmoiditis and colitis. Typical colonic ulcers contain many amebae with neutrophilic reaction and undermining edges. Infection may cause extensive ulcerating lesions with mucoid and puriform, partially bloody discharges, fever, abdominal pain, and severe tenesmus, or it may remain clinically inapparent for a long period. Rarely, the spread of infection via lymph or blood may cause localized abscesses in the liver, in the lung, or in the brain.

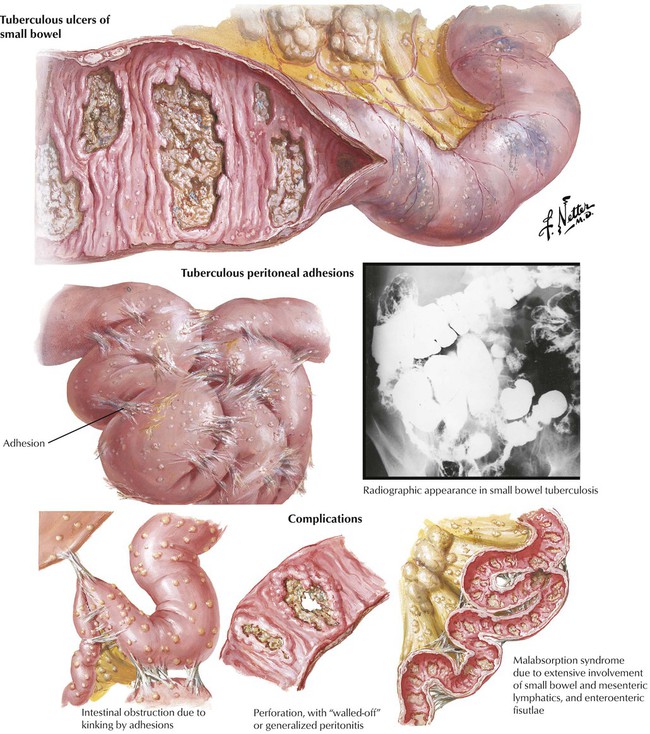

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis, which follows primary infection of the GI tract with M. tuberculosis bovinum, is rare in Western countries. Endoscopy reveals typical tuberculous ulcers (granulomas with caseous necrosis and ulceration) perpendicular to the intestinal axis. Bacterial superinfection with puriform ulcers may blur the characteristic features. Intestinal tuberculosis is accompanied by prominent focal peritoneal fibrosis with subsequent adhesions, shrinkage, bowel obstruction, fecal stasis, and perforation. Lymphatic spread of the infection is followed by multiple small peritoneal granulomas, which add to the peritoneal fibrotic process. Occlusion of intramural and mesenteric lymphatic channels may cause malabsorption. Treatment is a combination of tuberculostatic chemotherapy and surgery.

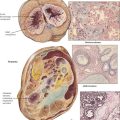

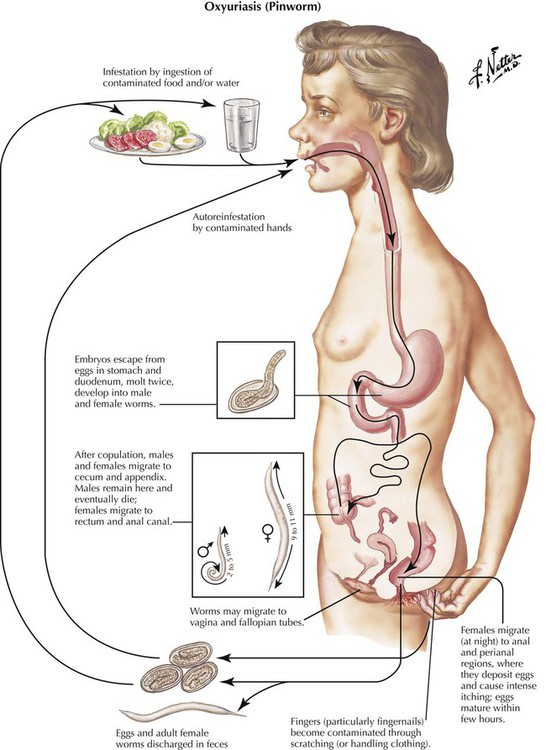

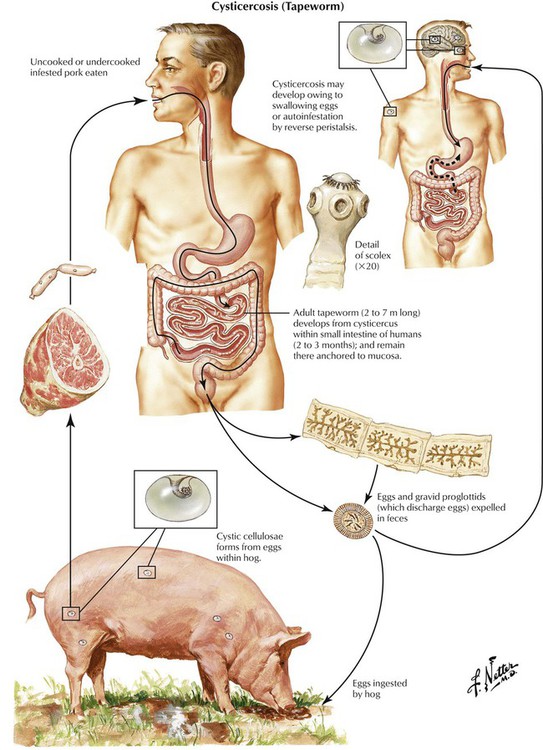

Parasitic disease of the GI tract follows infestation with various worms, including human whipworm (Trichocephalus trichuris), intestinal roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), human pinworm (Oxyuris vermicularis), beef tapeworm (Taenia saginata), and pork tapeworm (Taenia solium). The source of infection is contaminated foods with or without an intermediate animal host. Oxyuriasis and cysticercosis are shown here. Oxyuriasis occurs in children and can be the cause of poor growth and development. Pruritus ani (caused by worms leaving the anus) with frequent scratching, eczema, erosions, and eventual superinfection is a common symptom. Cysticercosis is caused by consumption of infested pork meat. Eggs from tapeworms in the small intestine develop into multiple cystic larvae (Cysticercus cellulosae) in organs and tissues, including muscle and the brain. Such isolated cysts may contain multiple “embryos,” which may promote further infestation and should be removed surgically.

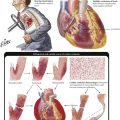

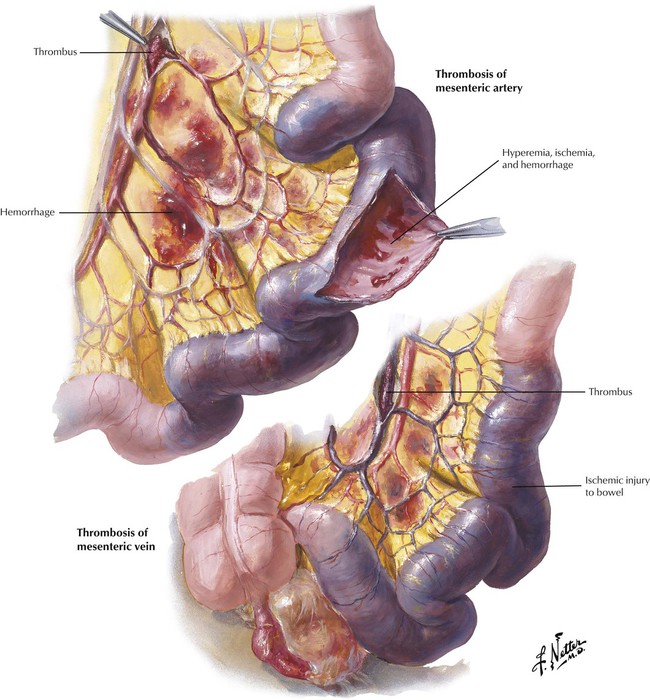

Mesenteric artery thrombosis or thromboembolism and venous thrombosis produce hemorrhagic infarction of the intestines because of overlapping vascularization. Arterial thrombosis may follow severe arteriosclerosis, systemic vasculitis, or a dissecting aneurysm. Left cardiac ventricular thrombi secondary to myocardial infarction, cardiac fibrillation, or endocarditis are the common sources of the thromboembolism. Venous thrombosis can follow abdominal trauma or surgery, sepsis, or hypercoagulation states. Whether the infarction is mural or transmural depends on the extent and duration of the vascular occlusion. There is massive hyperemia, hemorrhage, and progressive necrobiosis of tissue components (ischemic injury starts approximately 18 hours after occlusion). Bacteria migrating into the intestinal wall cause severe gangrenous enteritis and peritonitis and eventually perforation of the bowel. Early surgical resection of the infarcted area is the only lifesaving procedure.

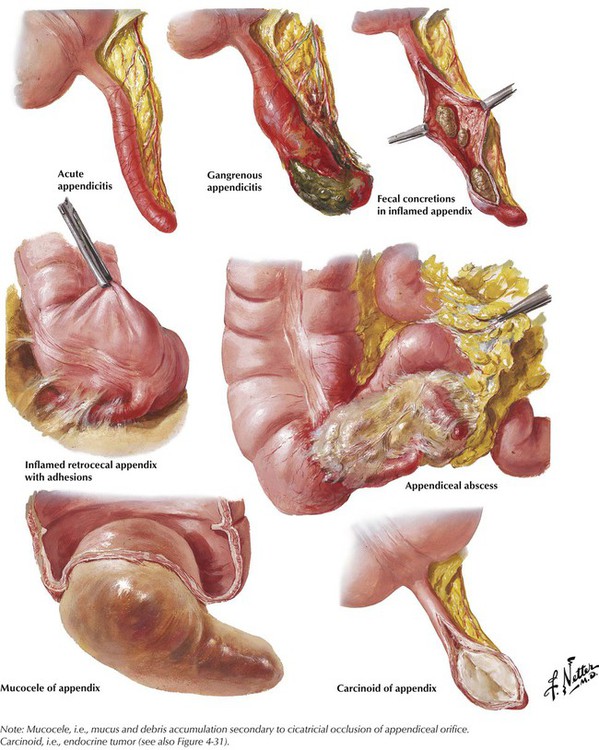

Acute appendicitis (AA) (i.e., acute catarrhal or puriform inflammation of the appendix vermiformis) is the most frequent reason for laparotomy. AA is commonly caused by bacterial infections, sometimes after fecal stasis or oxyuriasis (pinworm infection). Acute pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen is often accompanied by fever, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. A circumscribed tenderness in the right lower quadrant on palpation and increased blood leukocyte counts complete clinical diagnosis. Surgical removal of the appendix to avoid complications such as penetration of infection and perityphlitic abscess, perforation and generalized peritonitis, and, more rarely, puriform endophlebitis and liver abscesses is the treatment of choice.

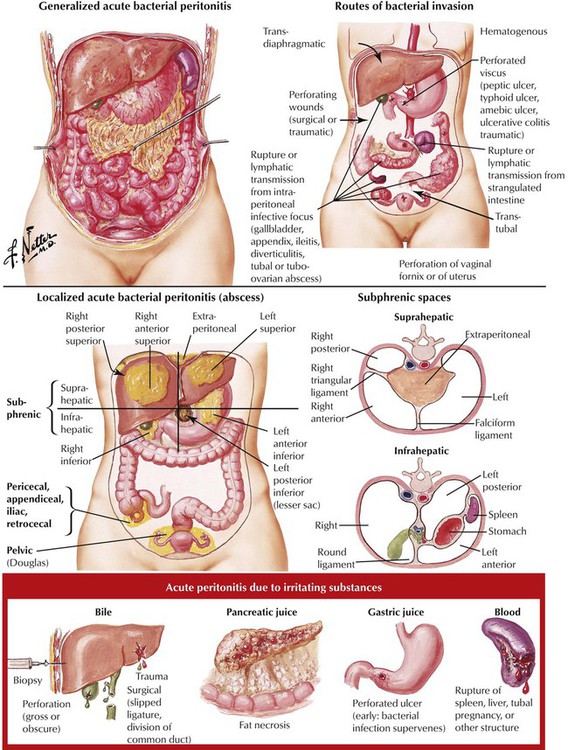

Acute peritonitis, an inflammation of the peritoneum, is caused by bacterial invasion or chemical irritation. It is usually a complication of perforation of the intraabdominal organs (ruptured appendix, perforated ulcer, diverticula), abdominal surgery, or peritoneal dialysis. Pathologic changes are those of a typical fibrinopurulent, gangrenous, or fecal inflammation with fibrous adhesions and concretions of bowel loops. Symptoms include those of acute abdomen (nausea, vomiting, diffuse abdominal tenderness and pain, abdominal distention, reduction of intestinal motility, or paralytic ileus, with ensuing high fever and septic shock). Treatment consists of antibiotics, surgical drainage, and/or debridement and supportive measures.

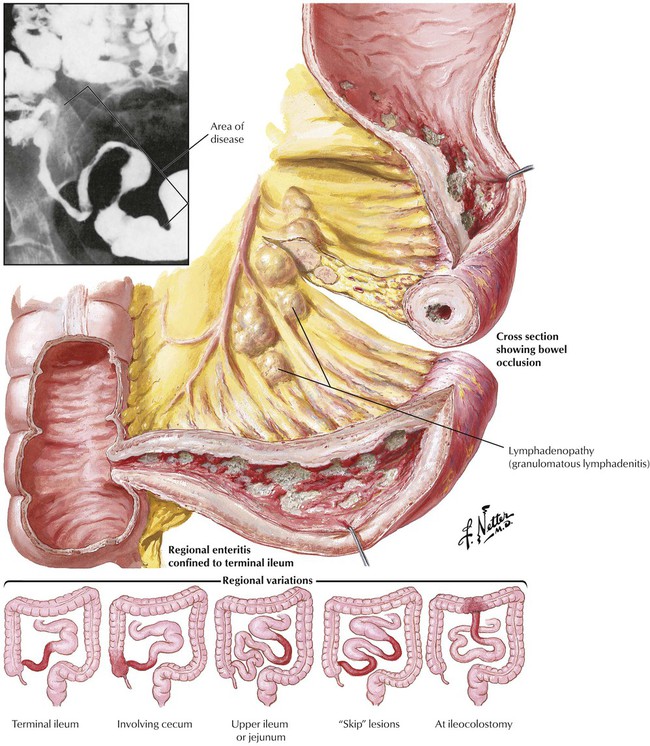

Crohn’s disease (enteritis regionalis) is a chronic granulomatous disease of the GI tract, mainly of the terminal ileum. It affects approximately 5 per 100,000 persons per year, with young adults of European ancestry affected most prominently. The etiology remains unknown, although family studies suggest a genetic susceptibility. Characteristic histologic changes are transmural edema (with subsequent fibrosis), nodular and follicular lymphocytic infiltrates, epithelioid cell granulomas, and fistulation. Inflammatory infiltrates are patchy with unchanged intestinum in between (“skip lesions”) and extend to involve the adventitial fat tissue (“creeping fat”) and regional lymph nodes. Symptoms include diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, and recurrent fever and malabsorption. Intestinal obstruction and fistulation may necessitate surgery.

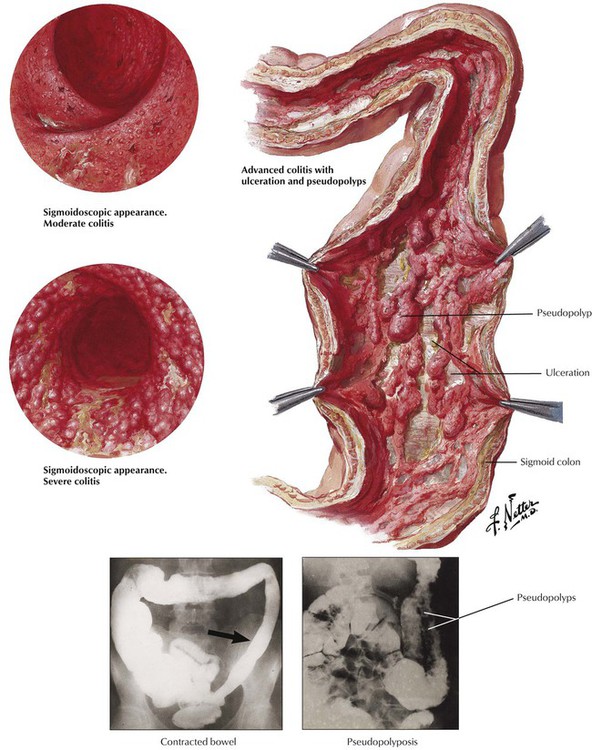

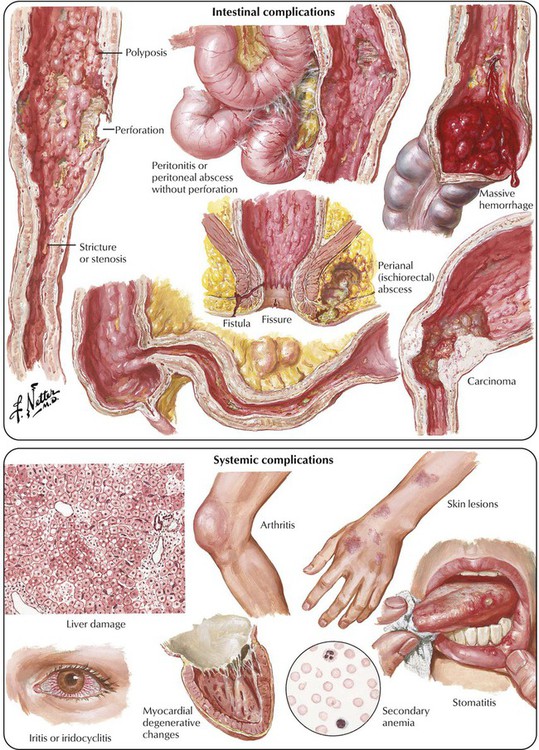

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of unknown etiology. Systemic complications may affect the liver, the joints, the heart, the oral mucosa, and the eyes. The tendency of UC to run in families suggests a genetic predisposition. The association of UC with autoimmune disorders (e.g., sclerosing cholangitis, migratory polyarthritis) suggests an immune component to the disease. Histologic investigation reveals a mucosal, erosive, and ulcerative colitis with neutrophilic infiltration (neutrophils in glands: cryptal abscesses), epithelial regenerative changes with elongation of neck area of crypts, and spreading of regenerating cells to the mucosal surface. Increasing epithelial atypia in prolonged disease may lead to adenocarcinoma. In late stages of the disease, epithelial regeneration and formation of pseudopolyps cause a “cobblestone appearance” of the mucosa between ulcerations.

Obstruction of the bowel (OB) is any mechanical or functional impediment of the normal propulsion of bowel contents. In newborns, congenital abnormalities, including atresias (esophagus, gastral, intestinal, anal), malrotation and volvulus, and aganglionic segments (colon), may cause OB. Mechanical obstruction by meconium (meconium ileus) or, at later age, by hernia, incarceration, and volvulus (peritoneal bands) must be considered. In adults, OB may result from ingested materials, spastic or cicatricial occlusion, compression from the outside (hernia, intussusception, volvulus, tumors), and chronic inflammatory diseases. When OB results in intestinal ileus, no bowel movement sounds are heard on auscultation (“silent abdomen”).Abdominal radiography shows distended small or large intestinal parts or both with accumulation of gas and fluids. Complications include paralytic ileus, infarction, invasion of the intestinal wall by enterobacteria and peritonitis, perforation, fecal peritonitis, and (septic) shock.

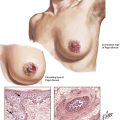

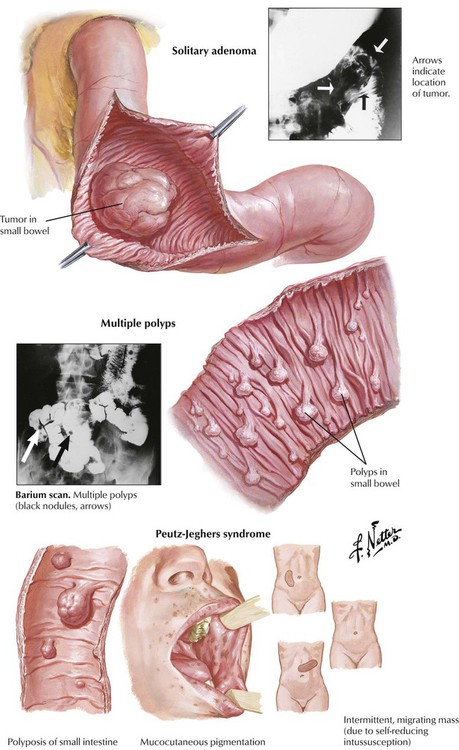

Most polyps and adenomas in the small intestine are benign sessile or pedunculated intraluminal tumors, which cause irregularly arranged intestinal glands and increased mucus production. Solitary tumors are rare. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), a heritable small bowel polyposis, consists of multiple hamartomatous polyps in combination with abnormal mucocutaneous (perioral, buccal, perianal) pigmentation. PJS is associated with mutational inactivation of a protein kinase encoded on chromosome 19p (gene LKB1). Bleeding, anemia, and intussusception are common complications. Tumor development is very rare, and it does not necessarily occur within the polyps. (See also Fig. 1-10.)

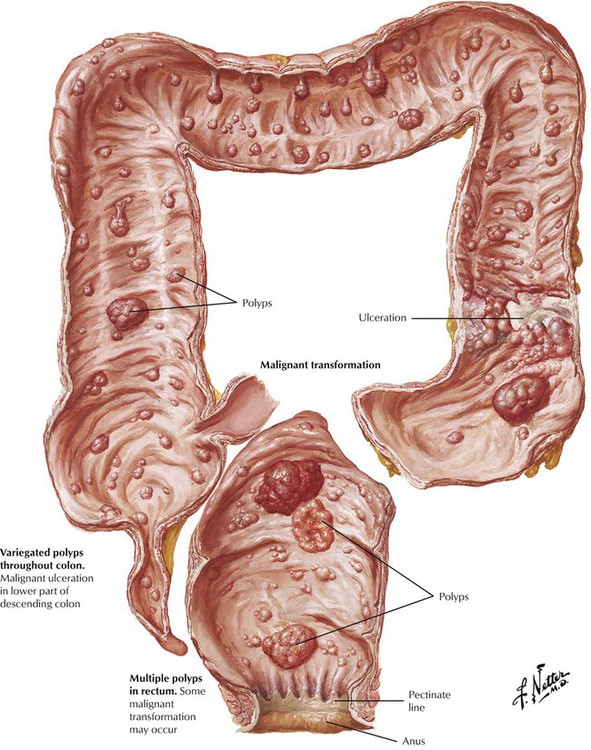

Familial polyposis of the large intestine is an autosomal dominant inherited disease, which, in contrast to PJS, consists of true adenomas (familial adenomatous polyposis) scattered throughout the large bowel. The risk of malignant transformation as early as the age of 40 years approaches 100%. Many adenomas are tubular adenomas; others are tubulovillous or villous adenomas. The disease is characterized by a germline mutation of chromosome 5 (5q21). Gardner syndrome combines a familial polyposis syndrome with extraintestinal lesions such as soft tissue and bone tumors. Turcot syndrome describes familial polyposis syndrome in combination with malignant tumors of the CNS.

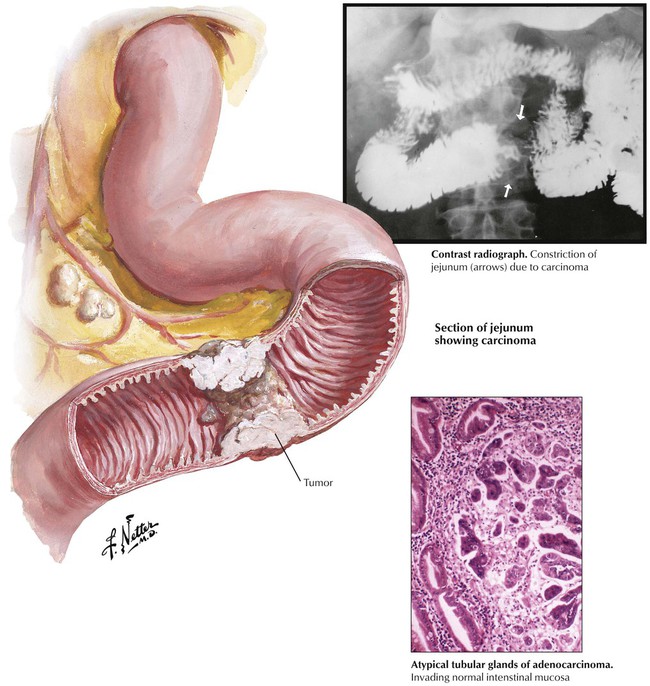

Malignant tumors of the small intestine, which consist of adenocarcinoma, malignant lymphomas, and CTs, constitute approximately 5% of all GI tumors. Adenocarcinoma presents as a circular constricting mass or as an intraluminal polypoid mass. Most adenocarcinomas are located in the duodenum and the jejunum. They are classified as glandular/acinar types, medullary carcinomas, or undifferentiated types based on their histologic characteristics. Chronic inflammatory diseases are a risk factor for the development of adenocarcinoma in the small bowel. Adenocarcinomas in the duodenum are frequently located within the ampulla vater (ampullary carcinoma) and cause obstructive jaundice or pancreatitis or both.

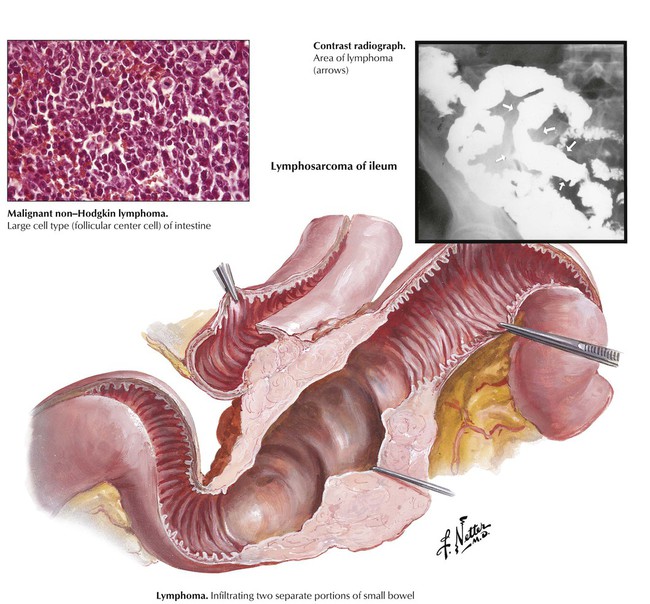

Primary malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a common tumor in the small intestine. It occurs in 2 major forms: Mediterranean-type lymphoma (immunoproliferative small intestinal disease [IPSID]), and Western-type malignant NHL. IPSID, with higher incidences in underdeveloped populations, appears infection-related and consists of progressive proliferation of IgA secreting plasmacytoid B lymphocytes (alpha chain disease) with signs of malabsorption. The terminal stage consists of an overt immunoblastic NHL. Western-type NHL tends to develop in the ilium as tumorous plaquelike infiltrates or intraluminal fungating masses, which result in bleeding, obstruction, and occasional intussusception. Histologically, these tumor cells, which consist of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), are referred to as MALT lymphomas. Follicular center cell lymphomas and other types may also be found.

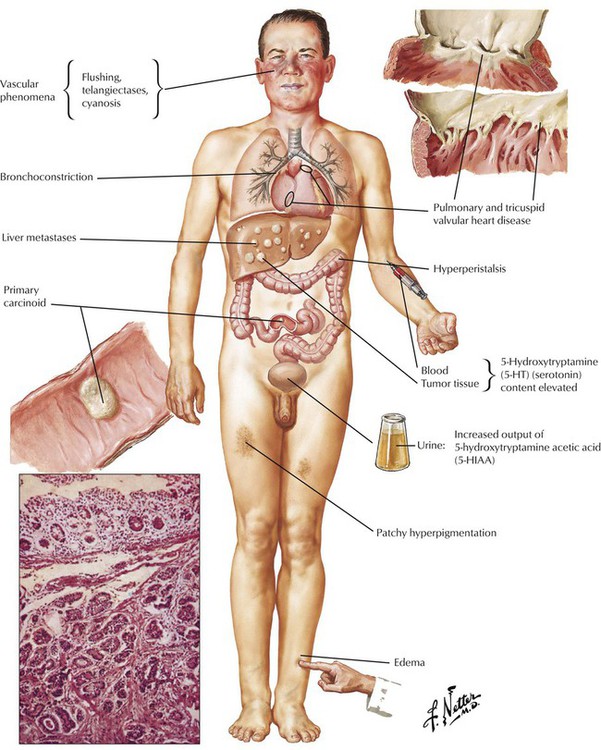

Carcinoid tumors (CCTs), which account for approximately 20% of small intestine tumors, can occur in other organs, including the intestines, the stomach, the liver, and the lungs. CTs are derived from argentaffine endocrine cells (enterochromaffin cells or Kulchitsky cells). CTs can occur as multiple isolated tumors or as part of a systemic disease (multiple endocrine neoplasia [MEN], type I). CTs less than 1 cm in diameter rarely behave malignantly and usually do not metastasize, whereas 50% or more of tumors 1 cm or larger with the same gross and histologic features metastasize. The tumor spreads most frequently to the liver. Carcinoid syndrome (diarrhea, flushing, bronchospasm, cyanosis, and skin telangiectases) is caused by episodic massive serotonin production by tumor cells. The 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) test, which measures 5-HIAA in the urine, is the diagnostic test of choice.

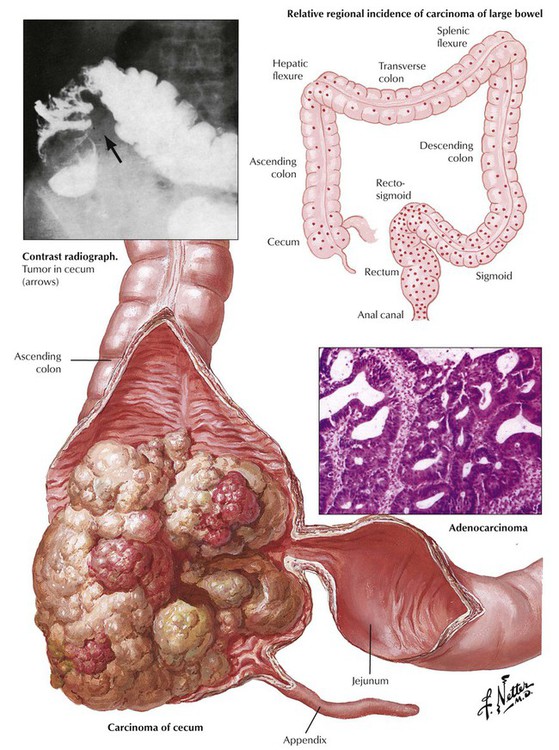

Adenocarcinomas account for 98% of all carcinomas in the colon and the rectum. They may develop de novo or from preexisting adenomas. Adenocarcinomas are located most often in the sigmoid colon and the rectum, followed by the descending colon. They are less frequent in the transverse colon and rare in the ascending colon. The gross appearance of adenocarcinomas of the colon and the rectum is polypoid and ulcerating. Some are plaquelike, infiltrating, and circularly constricting; others are flat but deeply infiltrating and inconspicuous endoscopically. Most tumors are well-differentiated adenocarcinomas with some mucus secretion; a few are mucinous adenocarcinomas or signet ring cell carcinomas. The degree of differentiation influences spread and prognosis. Colonic adenocarcinomas spread by direct extension through the intestinal layers, to regional lymph nodes by invasion of lymph vessels, and to the liver through the portal vein. Tumors in the deep sigmoid colon and rectum spread to the lungs hematogenously via tributaries of the vena cava inferior.