33 Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Gastrointestinal symptoms and distress are relatively common in children and are not limited to those receiving palliative care. Tummy-aches and vomiting are integral to the childhood portrayed by Shakespeare with his ‘mewling and puking’ infant, and the nursery rhymes and songs of childhood where ‘Miss Polly had a dolly that was sick, sick, sick’ and on the good ship Lolly-pop where ‘if you eat too much, oh, oh, you’ll awake with a tummy-ache.’ As many as 30% of otherwise healthy children will experience recurrent abdominal pain during childhood, one in six adolescents report functional gastrointestinal symptoms consistent with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS),1 and abdominal discomfort maybe the primary presenting symptoms for the child with anxiety and emotional difficulties.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are prominent among children receiving palliative care. Six studies examining the prevalence of distressing symptoms in a total of 592 children with malignant and non-malignant diseases reveal that the majority of dying children experience pain, 53% to 92%, and fatigue, 52% to 97%, during their end-of-life period. In addition, a large percentage suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and/or nausea, 40% to 63%, constipation, 27% to 59%, and diarrhea, 21% to 40%.2–7

This chapter aims to provide treatment algorithms for individual gastrointestinal symptoms as originally proposed in 2000.8 The evidence for any recommendations made is often poor due to the lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in pediatric palliative care and, unfortunately, pediatrics continues to be hampered by the common, unacceptable problem of many medications not being approved for use in children or for the specified indication resulting in off-label use.

Nausea and Vomiting

Pathophysiology

Toxins commonly associated with nausea and vomiting during the pediatric end-of-life period include medications such as chemotherapeutic agents, antibiotics, and opioids, and metabolic byproducts of uremia or hepatic failure.10

The majority of receptors in the vomiting center and CTZ are excitatory, that is, they induce nausea and vomiting with stimulation. An important exception is the presence of the μ-opioid receptor in the vomiting center. Opioids seem to have a dose-dependent interaction on emesis. At standard doses, opioids may cause nausea by stimulating D2-receptors in the area postrema but at high doses opioids are often not emetic. This is postulated to be due to an antiemetic or inhibitory effect at the μ-opioid receptor in the vomiting center.9,11

Opioid-Induced Nausea

Although individual patients may tolerate one opioid better than another, data suggest that prevalence of these side effects differ greatly among the commonly used opioids. Children usually develop tolerance to nausea, however this may take days to occur. From experience the single most helpful approach to opioid-induced nausea in the Minneapolis pediatric pain and palliative care patients represents a rotation or a switch to another opioid at an equianalgesic dose.12

Alternatively, low-dose naloxone infusions, at 0.25–1 mcg/kg/h, can reduce the frequency and severity of nausea without antagonizing analgesia in children who receive opioids.13 Infusion rates used are several-fold lower than infusion rates typically used to produce measurable reversal of analgesia or respiratory depression.

Treatment algorithm

Step 3: Implement Integrative and Supportive Therapies

The combination of supportive and integrative modalities with pharmacologic management should be seen as a gold standard to any pain and symptom management approach in the twenty-first century.14 Integrative and supportive approaches include the provision of small meals chosen by the child, frequently offering favorite drinks, good oral care, and the avoidance of discomforting smells.

Management of anxiety for the child and his or her family is paramount and should start with careful explanation of the likely factors contributing to the symptoms. A number of therapeutic techniques can be used to help the child to relax, feel calmer, and have a greater sense of control. These include cognitive behavioral strategies such as simple relaxation exercises, controlled breathing, and focusing on positive self messages and imagery. Younger children may need a parent to cue them and help them with guided imagery and stories, while older children can be taught self-hypnosis to manage symptoms. Pleasant masking aromas of the child’s choosing can also be used if there are particular odors that trigger nausea. Scheduling enjoyable distracting activities including music, or acupressure or acupuncture may also be useful for some children.9,15–20

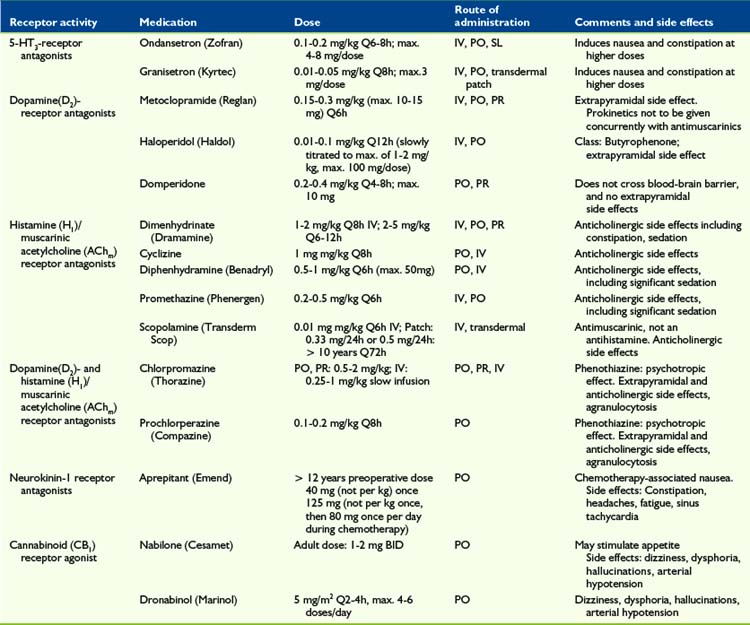

5-HT3-Receptor Antagonists

Several RCTs showed that the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine-3) antagonist ondansetron (Zofran) provides a good antiemetic effect in children with cancer after chemotherapy administration or bone marrow transplant,21–24 compared with placebo and other antiemetics such as metoclopramide plus dexamethasone25 or metoclopramide plus diphenhydramine.26 Other 5-HT3 antagonists, such as tropisetron (Navoban)27,28 and granisetron (Kyrtec)29 show a similar effect.

D2-Receptor Antagonists

Dopamine2-receptor antagonists such as metoclopramide (Reglan) and haloperidol (Haldol) are prokinetic and have been clinically effective in treating nausea and vomiting in pediatric palliative and hospice care. Stress, anxiety, and nausea via peripheral dopaminergic receptors at the plexus myentericus may cause a slowing of gastrointestinal passage, the so-called dopamine break. This effect is antagonized by metoclopramide (Reglan) and domperidone (Motilium).30 Other D2-receptor antagonists may have a similar effect.

They may, however, be underused due to an overemphasis on possible extrapyramidal reactions. Metoclopramide has been associated with a dyskinetic syndrome and reported to occur with an incidence of 1:5000 in teenagers.31 Any such reaction can be treated with either a centrally acting antihistamine, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl), or central anticholinergic, such as benztropine. This concern extends to a lesser extent to phenothiazine derivates (psychotropics) such as haloperidol (Haldol), prochlorperazine (Compazine), and chlorpromazine (Thorazine). Chlorpromazine and prochlorperazine are also H1– and AChm– receptor antagonists.

NK1-Receptor Antagonists

Aprepitant (Emend), a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, possesses antidepressant, anxiolytic, and antiemetic properties. NK1 receptors can be found in the central and peripheral nervous system, as well as the gastrointestinal tract. RCTs indicated it to be superior to ondansetron 24 to 48 hours post-surgery when given as a single pre-operative dose32,33 but, in general, pediatric data is scarce.34 One RCT (n = 46) in adolescents with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting showed the combination of aprepitant (125 mg IV TID), dexamethasone, and ondansetron to be superior to dexamethasone and ondansetron alone.35

Cannabinoids

The activation of the endocannabinoid system suppresses behavioral responses to acute and persistant noxious stimulation, and d-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) has been shown to have an antiemetic effect.36 THC can also stimulate appetite in addition to minimizing nausea.

Two types of cannabinoid receptors have been identified, CB1 and CB2. CB1 receptors are found in the central nervous system, including periaqueductal gray, rostral ventro-medial medulla and in peripheral neurons, where activation produces a suppression in intestinal neurotransmitter release.37 Dronabinol and nabilone do not fully replicate the effect of total cannabis preparations38 but a meta-analysis of 30 RCTs (n = 1366 patients)39 showed cannabinoids to be effective for controlling chemotherapy-related sickness in adults. Adverse effects included dizziness, dysphoria, depression, hallucinations, paranoia, and arterial hypotension.

Corticosteroids

Nausea caused by raised intracranial pressure secondary to a brain tumor may show dramatic short- to medium-term improvement with corticosteroid administration. Agents such as dexamethasone are thought to act by reducing the peri-tumor edema. In addition, corticosteroids inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which may also play an antiemetic role. Because of the significant side effect profile, including mood swings and excessive weight gain, associated with this class of drugs use in palliative care is controversial.40

Benzodiazepines

Low-dose benzodiazepines, such as midazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam, can be a part of an effective antiemetic drug treatment in pediatric palliative care. However, there is only limited pediatric data with RCTs showing effectiveness for postoperative nausea41,42 and chemotherapy-induced nausea.43,44

Propofol

Propofol possesses antiemetic properties at subhypnotic doses.45,46 The mechanism of action of this short-acting hypnotic and general anesthetic is not well defined and possibly includes potentiation of GABA-A receptor activity,47 sodium channel blocking activity,48 and activation of the endocannabinoid system.49 One adult case study reports successful nausea management in palliative cancer care at 0.6–1 mg/kg/h intravenously.50 Little pediatric data is published51 but the experience of the program in Minnesota with low-dose propofol in 12 children and teenagers52 points to it having an important role in managing refractory pain and nausea at the end-of-life when other agents fail (Table 33–1).

Constipation

Chronic constipation is common in children with underlying neurologic impairments related to longstanding poor tone and immobility, while in children with cancer intra-abdominal tumors can cause direct compression of the gut or spinal cord compression.10

Treatment algorithm

Step 2: Treatment of Underlying Causes

Underlying causes of constipation should be treated, if possible. In addition to the previously mentioned common reasons for constipation, consideration should be given to management of anorexia (see following text), weakness, decreased abdominal muscle tone, inconvenient toilet access, poor posture, and psychological factors such as depression. More specific pathologies to consider are hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, bowel obstruction (see later text), and adverse effects of medication.53

Step 3: Implement Integrative and Supportive Therapies

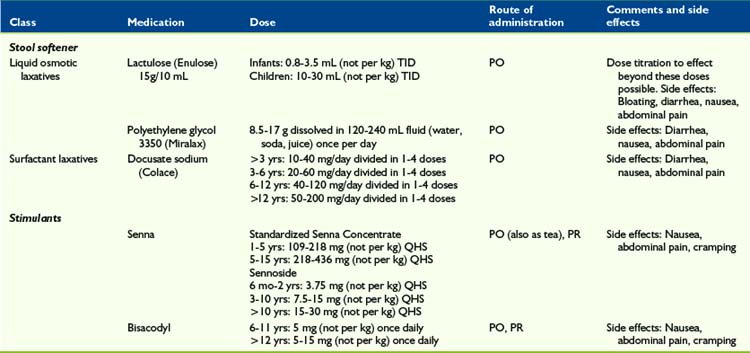

Stool Softener

Outside the United States, the most commonly used stool softener in pediatrics appears to be the sugar lactulose, a combination of galactose and fructose (Enulose).54,55 Lactulose does not affect the management of diabetes mellitus. In North America, polyethylene glycol (Miralax) is frequently used instead, and has also shown to be effective and safe.54,56–58 Lactulose’s advantage over polyethylene glycol is the much smaller volume, which is beneficial in the pediatric palliative care setting, where children often have trouble taking medication orally. All laxatives, including stool softeners, may cause abdominal pain and meteorism.

Stimulant laxatives

Children with a full rectum containing soft feces, or those for whom stool softeners were ineffective as a single approach, may be treated with a stimulant laxative such as senna59 or bisacodyl, to stimulate bowel motility. These medications act by stimulation of the myenteric plexus. However, stimulants alone can be dangerous when there is obstruction or impaction.53

Contrary to conventional wisdom, that stool softeners should be administered with stimulants, one recent RCT (n = 60 adults) treating opioid-induced constipation, showed that sennosides alone were superior than sennosides plus docusate.60

Prokinetics

If gastrointestinal hypoactivity is a presumed pathophysiology, then prokinetics such as low-dose metoclopramide or low-dose erythromycin,61 5 mg/kg QID, may be considered.

Suppositories and Enemas

Enemas may be required if the constipation is unresponsive to combined scheduled stool softeners and stimulant laxatives. Adult data shows that sodium phosphate/sodium biphosphate enemas, or saline rectal laxatives, and docusate sodium/glycerin mini-enemas, or surfactant rectal laxatives, are equal in efficacy.62 However, the latter is usually preferred in pediatrics because of its much smaller enema volume of 2.5–5 mL compared with 130 mL.

Naloxone

The oral administration of naloxone anecdotally seems to have good effect in adult palliative care. Dose suggestions include 20% of oral morphine equivalent divided into one or several doses.63 There is no published data about the intravenous administration of ultra-low-dose naloxone for constipation management, however the Minneapolis team has had several pediatric cases with very good results in their pediatric palliative care population with a dose of 0.25–1 mcg/kg/hr.

Alvimopan

Alvimopan (Entereg) is a peripherally acting μ-opioid antagonist, with limited ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. One adult RCT showed good effect without evidence of opioid analgesia antagonism, with an adult dose of 0.5 mg BID PO.64

Methylnaltrexone

Methylnaltrexone (Relistor) is a quaternary amine μ-opioid-receptor antagonist, and has restricted ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. An adult RCT showed good effect and treatment did not affect central analgesia or precipitate opioid withdrawal with an adult dose of 0.15 mg/kg every other day subcutaneously.65 It is unclear, whether or not this medication may be administered intravenously. Pediatric trials, although undertaken, have not yet been published (Table 33-2).

Diarrhea

Treatment algorithm

Step 1: Evaluation and Assessment

A child suffering from diarrhea in palliative care needs to be evaluated, which includes taking a careful history and performing a clinical exam. Common causes of diarrhea include gastroenteritis, malabsorption, laxative overuse, overflow constipation, fecal impaction, adverse effects to medication such as antibiotics or chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or concurrent illness, such as colitis. Anal leakage may occur following surgical or pathological injury to the anal sphincter.66

Step 2: Treatment of Underlying Causes

Severe diarrhea resulting in dehydration may require oral rehydration with electrolyte/glucose solution. If possible and feasible in the individual child, underlying causes of diarrhea should be treated. Frequent treatable causes include:67,68

Step 3: Implement Integrative and Supportive Therapies

Integrative and supportive therapies in the management of diarrhea in pediatric palliative care may include:67

Step 4: Pharmacologic Management

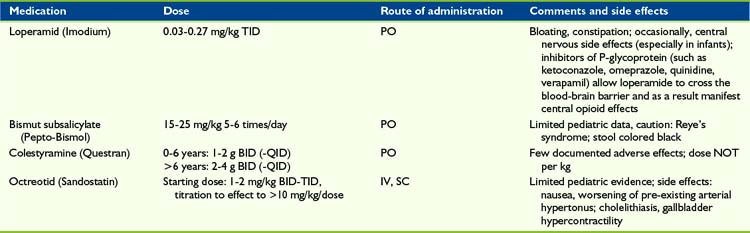

Loperamide

Loperamide is a potent μ-receptor opioid agonist and, although well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, it is almost completely metabolized by the liver and excreted via the bile. Loperamide does not cross the blood-brain barrier. As a result this agent acts via a local effect in the GI tract. However, it may take 16 to 24 hours for loperamide to show maximum effect in diarrhea treatment.70 As with morphine and other opioids, loperamide decreases propulsive activity, but unlike other opioids also has an antisecretory effect.71 If toxic substances are the pathophysiologic basis of diarrhea and need to be excreted, then the use of loperamide is not recommended.

Although three pediatric trials (n = 95) did not show a significant lorapamide effect,72–74 four other trials were able to demonstrate a decrease in stool frequency and duration of diarrhea.75–78 A case series of 15 children with chronic diarrhea following resection of advanced abdominal neuroblastoma, possibly resulting from disruption of the autonomic nerve supply to the gut during clearance of tumor from the major vessels of the retroperitoneum, demonstrated that loperamide reduces but did not abolish symptoms.79

Adverse effects, such as constipation or bloating, were uncommon in these trials and case reports. However children, especially infants, occasionally demonstrated central nervous side effects such as opioid over-sedation. Of note, inhibitors of P-glycoprotein such as ketoconazole, omeprazole, quinidine, and verapamil allow loperamide to cross the blood-brain barrier and as a result manifest central opioid effects.80 An overdose of loperamide in 216 cases has not resulted in life-threatening adverse effects or deaths with doses up to 0.94mg/kg.81

Bismuth subsalicylate

The mechanism of bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) is not well understood. A decrease in length of acute diarrhea symptoms could be shown in children with acute82,83 and chronic70,84 diarrhea. To prevent Reye’s syndrome, this medication and other salicylates should not be administered in children with viral infections.85 The administration of bismuth subsalicylate may result in black stools.

Colestyramine

Colestyramine (Questran) is a bile acid sequestrant, which binds bile in the gastrointestinal tract to prevent its reabsorption. Cholestyramine is primarily administered in the management of hypercholesterolemia, but also in the treatment of pruritus induced by liver failure and chronic diarrhea. Three pediatric trials74,86,87 (n = 78) resulted in a reduction in the duration of diarrhea. Case reports in the successful management of chronic pediatric diarrhea have been published.88–91 One study (n = 39 infants and children) showed treatments with cholestyramine and bismuth sub-salicylate were equally effective in decreasing stool frequency in patients with green diarrhea, such as following partial illeocolectomy or Candida albicans overgrowth, however children with brown stools had an insignificant response to therapy.70 Because cholestyramine is not absorbed systemically, there are no severe systemic side effects. Possible adverse effects, such as abdominal pain, flatulence, and constipation, were not reported in the pediatric literature.

Octreotride

In the management of secretory diarrhea, including carcinoid-associated, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) tumors, or AIDS, the administration of the somatostatin analogue octreotride may represent a successful approach. The secretory effect of several gastrointestinal active hormones. such as gastrin, colecystokinine, secretine, VIP, and motiline/ may be inhibited. Four case reports (n = 6 children) showed a successful approach in the treatment of chronic diarrhea caused by intestinal graft vs. host disease, cryptosporidium enteritis, and status post ileum resection.92–95 See Bowel Obstruction later in this chapter (Table 33-3).

Anorexia and Cachexia

At its simplest, anorexia is a loss of appetite, while the definition of cachexia has been disputed until recently. In 2008 a consensus definition for cachexia emerged as “a complex metabolic syndrome associated with underlying illness and characterized by loss of muscle with or without loss of fat mass.”96 Anorexia and cachexia are two interrelated symptoms that are often acknowledged together as the anorexia-cachexia syndrome.

The symptoms of anorexia and cachexia, assuming weight loss is a marker of cachexia, appear to be highly prevalent in children with life-limiting conditions of both malignant3,6,97 and non-malignant origin.3 In a study97 of 164 children and young people who died of progressive malignant disease, 48% had anorexia and 41% had weight loss on entering the study and these symptoms increased to just more than 67% in the last month of life, indicating anorexia and weight loss were not responsive to any treatments used. They were significantly more evident in children with CNS tumors when compared with leukemia and/or lymphoma or solid tumors. Similarly, a study6 reported a high prevalence of anorexia in children dying from cancer. However, this did not seem to result in a high level of suffering, but neither was it successfully treated.

A lower prevalence in the last week and day of life for anorexia, 33% and 24%, respectively, and weight loss, 20% and 21%, respectively, was found in 30 children dying in the hospital environment; 12 children had non-malignant conditions.6 They were not believed to cause undue distress to the child, but in more than half the children with the symptom were of moderate to severe intensity.

Anorexia-cachexia syndrome characterized by anorexia, involuntary weight loss, tissue wasting, weakness and poor physical function is a condition of advanced protein calorie malnutrition that inevitably leads to death98 if the underlying condition cannot be treated. In contrast to adults, children may manifest this problem as growth failure rather than weight loss.

Pathogenesis

The process of anorexia-cachexia syndrome is complex, but what is clear is anorexia, alone, is inadequate for the syndrome to develop. In normal circumstances the reduced caloric intake from anorexia results in a loss of fat stores, which stimulates an adaptive response to maintain the fat stores. This response is driven by declining levels of leptin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue. The consequence of low levels of leptin in the brain is for the hypothalamus to increase orexigenic signals such as neuropeptide-Y (NPY) to stimulate appetite and repress energy expenditure and decrease anorexigenic signals, corticotrophin-releasing factor and melanocortin, to achieve the same effect.98

This abnormal response has been suggested in a study99 that reported on the possible role of leptin and NPY levels as prognostic indicators in children with cancer. The study revealed a mean NPY level of 82.32 pmol/L and mean leptin level of 6.60 ng/mL at diagnosis in children who achieved complete remission, vs. a mean NPY and leptin level of 430.16 pmol/L and 0.192 ng/mL, respectively in those children who died with disease during the follow-up period. Furthermore, the mean NPY level declined and mean leptin level increased during the course of chemotherapy in the 23 children studied.

Evaluation and assessment

Laboratory tests evaluating nutritional depletion are of limited value100 and because they often cause a great deal of apprehension in children and young people cannot be recommended as routine. Albumin is the most common to measure because of its low cost and accuracy when liver and renal disease is absent.101 However, judicious testing for potentially reversible causes such as hypercalcemia are warranted.

Treatable causes

Integrative and supportive therapies

This approach can be supported by sufficient evidence102 that hypercaloric feeding does not increase lean tissue mass and there is no significant improvement in survival. Hypercaloric feeding particularly does not increase skeletal muscle mass, the loss of which is a defining96 event in cachexia.

There has been significant interest in the influence that more specific nutritional factors can have on cachexia with much of the focus on omega-3 fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). There has been a general trend in favor of EPA use from studies with a 2009 prospective, randomized; open-label study103 finding a decrease of cancer-induced weight loss in 33 children with cancer. The patients were fed a protein- and energy-dense nutrition supplement containing EPA when compared with 19 children who did not receive the supplements. However, a 2007 Cochrane review104 had concluded there was insufficient data to establish whether EPA was better than placebo in adults. This finding has been further supported by the publication of preliminary results of a randomized phase III clinical trial105 of 475 adult patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome who received one of five treatment arms (95 patients per arm) including pharmaco-nutritional support containing EPA. This arm of the study was withdrawn after analysis of 125 patients (25 each arm) indicated a worsening of lean body mass, resting energy expenditure, and fatigue compared with the other groups.

Psychological approaches should be seen as an extension of the exploration of emotional and spiritual issues and could include:100

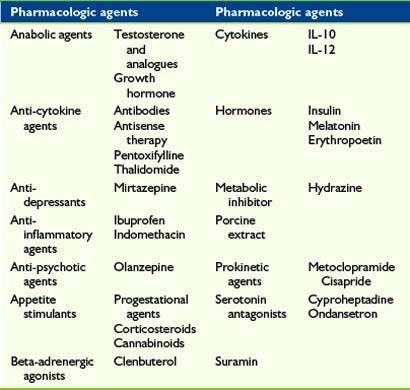

Pharmacology

Pharmacologic management of anorexia-cachexia syndrome is adjunctive to the integrative and supportive measures highlighted previously. This statement is supported by the finding that both anorexia and weight loss occur in high frequency and respond poorly to treatment in children and/or young people with progressive malignant disease.97 This suggests that available pharmacologic agents are not successful in alleviating these symptoms and this is further reflected in the large number of existing and experimental agents reported to be helpful (Tables 33-3 and 33-4). The data supporting the majority of medications are limited in adults and nonexistent in children. Arguably, the most studied medications are those of the progestational group of which Megestrol acetate has received the most scrutiny. This has culminated in a Cochrane review in 2005106 and an update in 2007. Megestrol acetate was demonstrated to improve appetite and weight gain in adult patients with cancer although this is largely due to fat rather than muscle mass, the tissue lost in cachexia. No overall conclusion could be drawn on quality of life because of statistical and clinical heterogeneity. Similarly, patient numbers and methodological shortcomings allowed no recommendations to be made about megestrol acetate use in patients with AIDS or other underlying pathologies.

Megestrol acetate has been trialed in a small number of children with cachexia, not necessarily at a time of palliation, due to cancer,107–109 cystic fibrosis,110,111 and HIV disease112 and reported to improve nutritional status by increasing appetite and weight. Adverse effects were significant, with most children studied reported to have adrenal suppression, with one child manifesting clinical hypoadrenalism with hemodynamic collapse requiring ionotropic support.108 This effect was shown to be transient109 as a normal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was returned once megestrol acetate was discontinued. However, replacement glucocorticoid therapy was advised during times of severe stress.

Cyproheptadine hydrochloride has been used in children with cancer and/or cancer treatment-related cachexia and shown113 to improve average weight gain by 2.6 kg and significantly enhance mean weight-for-age z-scores in 50 of 66 children. The main side effect was drowsiness. Seven of the nonresponding children then received megestrol acetate with five demonstrating an average weight gain of 2.5 kg with one child developing low cortisol levels and hyperlipidemia.

A preliminary report114 on the use of recombinant human growth hormone in four HIV infected children with failure to thrive suggested mean fat-free mass and weight gain were increased with no deleterious effect on disease control.

Distressing Symptoms of Mouth and Throat

Mouth care

The care of a child’s mouth during palliative care is an essential element of his or her overall care and one in which an informed child and family can take a lead role. This can be associated with an improved quality of life, create a sense of control and prevents mouth care from being overlooked. This aspect of palliative care for children has been well documented115 with respect to children with cancer, with many of the recommendations applicable to children with life-limiting illnesses of non-malignant origin.

Evaluation and Assessment

The majority of problems will be readily diagnosed with nothing more than a good history and a look inside the mouth. A number of oral assessment tools have been reviewed115 with only one tool, Eiler’s Oral Assessment Guide,116 being identified as user-friendly and appropriate for everyday clinical use in children and adults. This guide covers the assessment of voice, ability to swallow, lips, tongue, saliva, mucous membrane, gingival, and teeth and/or dentures.

Treatable Conditions

There are a number of potential conditions and/or symptoms that may require management, including:

Integrative and Supportive Therapies

The mainstay of preventing the development of mouth problems is maintaining the twice-daily routine of careful and gentle cleaning of the teeth and gums with a fluoride toothpaste.115 This should also apply to cooperative severely disabled children. Mouth-care sponges dipped in mouthwash can be applied to the gums and teeth in the unconscious or less-cooperative child. This has the added advantage of keeping the mouth moist. Cream or soft white paraffin can be applied to the lips to prevent dryness and cracking.

Pharmacology

Pharmacological management is detailed in Table 33-5. Management of xerostomia is dealt with in Table 33-6.

| Condition | Pharmacologic management |

|---|---|

| Candidiasis | Use absorbed or partially absorbed anti-fungal agent such as fluconazole for visible thrush117,118 |

| Ulceration | |

| Bleeding gums120 |

TABLE 33-6 Management of Non-Specific Xerostomia

| Supportive measures | Pharmacologic measures |

|---|---|

* Pilocarpine use in children is limited to a case study of one child receiving this drug to prevent xerostomia.

Xerostomia

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, has a reported prevalence3 of about 40% during the last week of life and causes quite a bit to very much distress at a similar level as pain. It results from a reduction in saliva secretion, particularly the serous component. This can lead to difficulties with eating and speaking and contribute to anorexia, changes in taste, and increase the risk of oral infections.

Throat problems

Dysfunction of the throat, esophagus, and upper stomach in the form of dysphagia and gastroesophageal disease (GERD) are not uncommon in the palliative care of children, with the most affected group being those with neurological impairment. This group has been reported122 to have an aspiration prevalence of 68% to 70% and a silent aspiration rate of 94%.123 They generally enter services with these conditions identified and managed but these symptoms can develop or, in the case of GERD, be unrecognized.120

Troublesome hiccups are a less common problem but can be a source of considerable challenge.

Dysphagia

The prevalence of dysphagia has been reported3,97 to be a significant problem in 23% to 30% of dying children during the last month of life, and in the palliative cancer population the prevalence increases with time.97

Evaluation and Assessment

Evaluation of dysphagia and other throat symptoms to be discussed requires a holistic approach that goes beyond observation of feeding123 and, in children at the end of life, may not require action once the wishes of the child and/or his or her family are considered.

The diagnosis can be made clinically and improves with experience.122 However, comparison of a therapist’s judgment to a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) only indicated a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 42% and positive and negative predictive values of 65% and 60%, respectively, for clinical evaluation to detect penetration of liquids. Disturbingly, the sensitivity, 70%, specificity, 55%, and positive, 41%, and negative, 80%, predictive values were inferior when detection of penetration of solids by clinical evaluation were analyzed.

Suggestive Symptoms

Symptoms associated with eating and/or drinking that may herald the presence of dysphagia include:

A retrospective analysis124 of various signs and symptoms of aspiration and dysphagia revealed wet voice, OR 8.9, wet breathing, OR 3.35, and cough, OR 3.3, to be good clinical markers for children aspirating on thin fluid, but not on purée. Age and neurological status influenced the significance of these clinical markers. The significant predictive qualities of cough for fluid aspiration and penetration had previously been determined.122 This same study also indicated the aspiration risk factor increased when other features such as voice changes, color changes, and/or delayed swallow were also present.

Treatable Conditions

More potential exists for dysphagia caused by symptoms associated with disease progression, such as:

Integrative and Supportive Therapies

The extent to which dysphagia is managed is dependent on the stage of the child’s palliation and the goals of the child and/or the family. A speech therapist’s involvement is advisable from the time of evaluation through to the child’s management. They are able to provide specific exercises to improve coordination and muscle strength or suggest individualized strategies to compensate for impaired swallowing function and enhance the ease and safety of oral intake125 (Table 33-7).

| General strategies | During feeding |

|---|---|

| Postural changes | Taking smaller mouthfuls |

| Changes in rate of food presentation | Chewing on the stronger side |

| Use of modified feeding tools | Double-swallowing |

| Modifications to amount and texture of food-softer consistencies, thickened fluids | Suctioning, when necessary |

Feeding Devices

A 2006 clinical report126 on the nutrition support for neurologically impaired children recommended, among other things, that enteral tube feedings be initiated early in children who are unable to feed orally or who cannot achieve sufficient oral intake to maintain adequate nutritional or hydration status. It also recognized that parental concerns and family issues have a role in the decision to provide aggressive nutritional support. The latter reflection, questionably, becomes even more valid when considering an interventional approach in the palliative care setting.

Both NG and GT are common pieces of equipment used to feed and/or administer medication in medically fragile children when there are undue risks with oral intake. However, NG or nasojejunal (NJ) tube feedings should be reserved for short-term nutritional intervention and GT or gastrojejunostomy (GJ) tube feedings may be used when long-term nutritional rehabilitation is required.126

The pros and cons for each device are relative to the situation and include the child’s medical condition, age, previous and future operations, and preference of the surgeon. The Malecot device is typically considered temporary, being replaced by a balloon device after 1 to 2 months, and removal does not require surgery. Removal of a balloon device requires only deflation of the balloon, but a PEG removal requires endoscopic extraction. Care of all feeding devices is important and has been well detailed in a 2003 best practice guideline from Scotland.127

In a study128 on the effects of tube feeding on 26 children, with 13 NG, 10 NG changing to GT, and 3 GT, for a mean of 23 months indicated a significant improvement from 73% to 94% in mean percent ideal body weight for height-age for the whole group. Seventeen parents perceived an enhanced mood in their child and they spent less time in caring for their child after NG or GT feedings began. No hospitalizations due to tube-feeding complications were reported.

A 2004 Cochrane review129 that highlighted the considerable uncertainty about the effects of gastrostomy for children with cerebral palsy remains because of the lack of well designed and conducted randomized controlled trials. Despite the lack of these trials an improvement in body weight was confirmed in a review130 of the benefits and risks for GT or GJ feeding in comparison to oral feeding for children with cerebral palsy. On the downside, there was an approximately fourfold increase in risk of death reported in one cohort of GT-fed children and many complications were reported, including potential for increased gastroesophageal reflux and fluid aspiration into the lungs. In 2006,131 published evidence refuted an increased respiratory risk to children with cerebral palsy following GT insertion.

Similarly, a prospective cohort study132 of 57 caregivers of Caucasian children with cerebral palsy detailed a significant, measurable (short-form 36 version II) quality of life at 6 months and 12 months after GT insertion. Improvements were noted in social functioning, mental health, energy and/or vitality, and general health perception. When compared to baseline data and values at 12 months, results were not significantly different from the normal reference data. The value of gastrostomy placement has conceivably been enhanced further by a prospective controlled study of children133 that found significant clinical benefit at no significant extra cost. The cost of food did increase post surgery from $65 to $78 per week with the mean net cost difference being $41 per week per child inclusive of food and surgery. Community service costs were significantly lower post surgery and few parents reported personal costs at either time point, although many had reduced or stopped paid work to care for the child.

Unfortunately, enhancements in the quality of life of neurological impaired children through use of feeding devices have not been so evident. A recent prospective report134 of 50 neurologically impaired children receiving either GT or GJ feeding noted the mean weight-for-age z-score and ease of medication administration increased significantly over time but there was no improvement in either their quality of life or health related quality of life over a 12-month period. Also, the eight children with a progressive neurological disorder had a significantly lower quality of life over time. Nonetheless, caregivers were of the opinion that GT and GJ tube feeding had a positive impact on their child’s health at 6 months (86%), and 12 months (84%).

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

In GERD, food or liquid travels backward from the stomach to the esophagus, resulting in symptoms from irritation of the esophagus. It is a common diagnosis in neurologically impaired children and infants, ranging from 15% to 75% of children,120 and children with cystic fibrosis and children nearing the end of life, especially when cachexia, general debility and restriction to the supine position are evident.

Integrative and Supportive Therapies

The presence of GERD in children and infants regularly leads to a number of lifestyle and nutritional change recommendations (Table 33-8). These have, most commonly, been considered in the context of relatively healthy children or infants with mild symptoms. They are unlikely to be successful as the sole modality of management for children with life-threatening conditions and/or moderate to severe symptoms.

| Recommended lifestyle and nutritional changes | |

|---|---|

There have been a limited number of studies even in the healthy pediatric population and two Cochrane reviews135,136 could find no evidence to support or refute the efficacy of feed thickeners in newborn infants with GERD. However, between the ages of 1 month and 2 years this strategy was deemed helpful in reducing GERD symptoms,135 but elevation of the head of the cot was not supported as a helpful strategy.

The adult literature has been reviewed in 2006137 with the evidence for the effect lifestyle measures had on GERD in adults pointed toward an improvement in the overall time esophageal pH was less than 4.0 through bed head elevation and left lateral decubitus position, while weight loss improved pH profiles and symptoms. Furthermore, there was physiologic evidence that exposure to tobacco smoke, alcohol, chocolate, and high-fat meals decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure but cessation of tobacco smoking and alcohol, and other dietary measures did not directly support betterment in GERD.

Surgical management of GERD may be a consideration for a child with a life-limiting illnesses and troublesome GERD that has not responded to medical management, although there is no evidence to support this claim.138 The most frequent surgery performed is the Nissen fundoplication, either as an open (ONF) or laparoscopic (LNF) procedure. It involves wrapping the upper part of the stomach around the lower end of the esophagus, allowing the lower esophageal sphincter to close more completely, reducing reflux.

This can be seen as a safe procedure with a median duration of 70 minutes and in a retrospective study139 comparing Nissen, Thal, and Toupet fundoplications for 238 children without neurological impairment, all three procedures were found to be equally effective with an overall 5% intra-operative and 5.4% post-operative complication rate. Only 2.5% of children required second operations, and all but 9 children were free of symptoms 5 years out from their operation.

Earlier, retrospective analysis140 of fundoplication for GERD in 52 neurologically impaired and 25 unimpaired children indicated that impaired children had significantly fewer hospital admissions and total days of hospitalization during the first 6-month post-operative period and a short-term weight gain improvement in those with failure to thrive (FTT). However, longer term (1 and 2 years post-operation) weight gain and weight gain in unimpaired children with FTT was not improved.

The advent of the laparoscopic approach made for a faster, safer procedure with a smooth postoperative recovery and similar failure rates.141 A retrospective review142 of 456 children with GERD who underwent ONF (n = 150) or LNF (n = 306) concluded that the majority of re-operations occurred in the first year after operation with LNF having a significantly higher rate than ONF; 10.5% vs. 4%. The probability for a further operation increased with co-morbidities, particularly prematurity and chronic respiratory conditions.

Pharmacology

Antacids+/- Alginate

Antacids provide only short-term stomach acid neutralization with each dose taken making them less effective, other than for short-term relief of symptoms. They contain aluminum, calcium, or magnesium or a combination of these chemicals, and as such long-term use cannot be recommended because it introduces the risk of toxicity. Toxicity examples include diarrhea with magnesium containing antacids, or the reported case143 of phosphate depletion-induced osteopenia in an infant on prolonged aluminum and magnesium hydroxide gel therapy for colic.

Aluminum/magnesium trisilicate (Gaviscon) has the added effect of serving as a protective barrier for the esophagus. It produces a viscous, demulcent antacid foam that floats on the stomach contents and in addition to reducing the frequency of reflux episodes, the alkaline foam aids the neutralization of refluxed gastric acids. Aluminum/magnesium trisilicate infant sachets were recently reported144 to be safe and able to improve symptoms of reflux.

Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RA)

This group of agents reduces acid production in the stomach by antagonism of the H2 histamine receptor. A comprehensive evidence-based review145 stated ranitidine to be safe and effective in infant GERD and the early use of H2RA’s was supported in older children. These medications are usually taken by mouth once or twice a day with intravenous, oral syrup and effervescent tablet forms available. The effervescent ranitidine tablets may be dissolved in water, fruit juice, and carbonated drinks and one tablet dissolved in 100 mL of water is stable for 24 hrs and a tablet is soluble in water volumes down to 15 mL.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs are highly selective and effective in their action of blocking the production of acid in the stomach at the final common metabolic pathway of gastric parietal cells. In a Cochrane review145 of adults with GERD symptoms, PPIs were found to be more effective than H2RAs (RR 0.66, 95%; CI 0.60 to 0.73) and prokinetics (RR 0.53, 95%; CI 0.32 to 0.87). In children they were found to be highly effective, have a very good tolerability profile and have few short- and long-term adverse effects.146 The safety and efficacy of omeprazole and lansoprazole were confirmed in a 2009 evidence-based systematic review.144 Both also promoted symptomatic relief and endoscopic and histological healing of esophagitis in infants with GERD. The evidence also supported the early use of proton pump inhibitors in older children.

The oral dosages recommended for infants and children are:

When children cannot swallow tablets or capsules, then omeprazole capsules can be opened and the granules mixed with an acidic drink and swallowed without chewing. In the case of PEG and NG tubes, the granules can be mixed with 10 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate and left to stand for 10 minutes until a turbid suspension is formed. The suspension is then given immediately and flushed with water. Lansoprazole fastabs dissolve very well in water and are less likely to block tubes.120

Prokinetic Agents

Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide and domperidone have been used in GERD and their action discussed in the section on nausea and vomiting. Unfortunately, two reviews135,147 could suggest only some benefit for infants under the age of 2 years with GERD from metoclopramide in comparison with placebo, but pointed out there was insufficient evidence to support or oppose use.

Hiccups

Hiccups are a physiological process involving a reflex148 consisting of the following:

Integrative and Supportive Therapies

Nonpharmacologic therapies including well-known traditional remedies, medical interventions and complementary therapies all work on sound physiological principles and can succeed by effecting components of the hiccup reflex. These have been well detailed:148

Pharmacology

A large array of pharmacologic agents can potentially be used to treat hiccups149 promoting the adage that the larger the variety of agents available to treat a symptom, the less likely they are to be helpful. The most positive evidence has arisen for the muscle relaxant, baclofen149,150 and, more recently, the anticonvulsant, gabapentin151–153 has been receiving favorable attention.

Bowel Obstruction

Pathogenesis

Obstruction in this setting occurs when the lumen of the bowel is sufficiently occluded to prevent the movement of intestinal contents along the gastrointestinal tract. In a report by the Working Group of the European Association of Palliative Care,154 several pathological mechanisms were detailed for adults with end-stage cancer and are likely to be the process for children. These are:

It is important to note that even in the adult patient with end-stage cancer, benign causes such as adhesions, post-irradiation bowel damage, inflammatory bowel disease, and hernia can be the cause of the obstruction in around half of the cases.155

Evaluation and assessment

The presentation of bowel obstruction is site-dependent, with symptoms determined by the sequence of distention- secretion-motor activity of the obstructed bowel.154 The symptoms most likely to occur involve a combination of pain, both continuous and/or colicky; nausea and/or vomiting; and constipation with or without overflow diarrhea. Vomiting is more likely to be a feature of, and develop earlier in, small bowel obstruction particularly that of the stomach and duodenum. Large bowel involvement tends to involve deeper pain of less severity, occurring at longer intervals.156

If further investigation is warranted, then a plain abdominal x-ray could show the presence of bowel distension and more than six gas-fluid levels on supine and erect films. In suspected small bowel obstruction, plain supine and standing films are required and have been reported157 to be as sensitive as computed tomography (CT) in adults. However, plain films are less sensitive for detection of low grade or partial obstruction. CT scan adds a more global assessment of disease and can assist in the choice of intervention: surgical, endoscopic, or pharmacologic palliation.154

Contrast studies provide information on the site and extent of obstruction, particularly partial obstructions, and can evaluate problems with motility. Barium, while it gives good definition, can cause problems with impaction because it is often not absorbed. Hyperosmolar water-soluble contrast mediums, such as Gastrografin, are safe and have a therapeutic role in that they are a predictive test for non-operative resolution of adhesive small-bowel obstruction with a pooled sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 96%.158 This review also indicated contrast did not reduce the need for surgical intervention but it did reduce hospital stay compared with placebo.

Integrative and supportive therapies

Management of bowel obstruction is primarily aimed toward the relief of symptoms and this does vary according to the presence of a partial or complete obstruction.159

Nausea and Vomiting

If a partial obstruction without colic is present, then a prokinetic agent such as domperidone or metoclopramide can be initiated and titrated to effect. Any worsening of symptoms necessitates this approach be discontinued and an anti-secretory agent commenced. The mainstay of treatment is hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan), with or without an anti-emetic agent that acts to slow intestinal transit such as cyclizine or methotrimeprazine. The somatostatin analogue octreotide can then be introduced if required.154 Hyoscine butylbromide is not available in the United States, the alternative is hyoscyamine (Levsin).

Corticosteroids have been used to provide temporary symptom relief and resolution of the obstruction through their edema-reducing and anti-secretory effects. However, two systematic reviews160,161 were unable to show statistical significance because of methodological weakness in existing studies but another study160 commented on a trend toward resolution of bowel obstruction with corticosteroid use.

Nasogastric Suction

The use of intravenous hydration and nasogastric suction fail to control the symptoms of inoperable bowel obstruction in around 90% of adults.162,163 It should be considered only a short term measure to deal with excessive secretions while pharmacologic treatment is established.

Gastrostomy

Gastrostomy placement can be operative or by percutaneous endoscopy. PEG placement can be done under CT guidance when there are concerning complicating factors, such as carcinomatosis, portal hypertension, or ascites. PEG is a superior technique to both NG and operative gastrostomy for palliation of small bowel obstruction,164 and overall this approach can control nausea and vomiting in more than 90% of cases of bowel obstruction.

Constipation

All laxatives should be stopped in complete bowel obstruction. However, the presence of a partial and intermittent block does allow for a trial of a softening agent such as docusate and the dose titrated to produce a comfortable stool without colic.159

Pain

Pain associated with bowel obstruction can be continuous, colicky and, in higher abdominal masses, involve the celiac plexus. Continuous pain frequently requires the use of a strong opioid, which may also alleviate colic. However, if colic is not satisfactorily managed by a strong opioid, then the addition of an anti-secretory drug is warranted.154

Surgery

The role of surgery in malignant bowel obstruction in adults with advanced gynecological or gastrointestinal cancer remains controversial with no firm conclusions by a systematic review.165 The literature lacked appropriate and validated outcome criteria, but prognostic criteria154 are available to select patients who are more likely to benefit from surgical intervention.

Pharmacology

Hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) and octreotide are the mainstays of pharmacologic management. In the United States, it is hyoscyamine (Levsin) and octreotide. In a qualitative systematic review of the limited data available161 octreotide was evidenced to be superior to hyoscine butylbromide in relieving gastrointestinal symptoms from inoperable malignant bowel obstruction in a total of 103 adult patients.

Hyoscine Butylbromide

In children the anti-spasmodic dose is 0.5mg/kg/DOSE with a maximum dose of 20 mg every 6 hours to 8 hours179 or a continuous infusion dose of 0.6–1.2mg/kg/24hr.40 The maximum continuous infusion dose has not been determined in children.

Octreotide

Octreotide is a long-acting synthetic analogue of endogenous somatostatin and a potent inhibitor of growth hormone, glucagon, and insulin. It also modulates gastrointestinal function by slowing intestinal motility, reducing gastric acid secretion, decreasing bile flow, increasing mucous production, and reducing splanchnic blood flow.166,167

In adults, octreotide reaches peak serum concentrations within 30 minutes of either an intravenous or subcutaneous injection, has a half-life of around 90 minutes and duration of action of approximately 12 hours, allowing for twice daily-administration. Elimination is prolonged in renal failure; it is metabolized and excreted unchanged. It can interact with cyclosporine to reduce serum concentrations and prolong the corrected QT interval at therapeutic doses.167

In children it has been reported to assist in the management of a range of gastrointestinal conditions,94,168–170 including chronic gastrointestinal bleeding171,172 and non-gastrointestinal disorders such as chylothorax167 and reversing hypoglycemia.173 Octreotide has also been described174 to improve the quality of life of a 12-year-old boy with malignant bowel obstruction by abating symptoms and improving appetite.

Dosing recommendations depend on the condition being treated, but usually range from 1-10 mcg/kg/dose every 8 hours with a maximum dose of 500 mcg. Octreotide has been given as a continuous infusion of 1-5 mcg/kg/hour175 for acute variceal bleeding and in children being treated for chylothorax infusions have been titrated up to 10 mcg/kg/hr with the duration of treatment ranging from 3 to 29 days.167

Feeding Intolerance

A large number of children with non-malignant life-limiting diseases receive part or all their feeding by tube, often by gastric and/or jejunal tube (PEG-tube). Data shows that a subgroup of those children develop a progressive intolerance to their feeds, clinically manifesting as worsening reflux, vomiting, abdominal bloating, ileus, irritability, and pain (in non-verbal children often described as “episodes of inconsolability” or “screaming of unknown origin”). This intolerance persists despite modifications to the artificial feeding rate or route, modifications to formula composition, and the addition of medications.176 These children have repeated episodes of intolerance to feeds before the end-of-life phase of their illness.

If a thorough workup does not reveal a pathophysiology, visceral hyperalgesia should be considered. The enteric nervous system contains more than 100 million neurons, both myenteric and submucosal ganglionated plexi, transmitting nociception via dorsal horn neurons, vagal afferents at the medulla, and thalamus to the sensory cortex. Viceral hyperalgesia may be based on alterations in response to bowel sensory input, which result in recruitment of previously silent nociceptors, resulting in sensitization of visceral afferent pathways. There is very limited pediatric data in the management of feeding intolerance and/or retching.177 Successful treatment strategies in our pediatric palliative care patients seem to include the administration of analgesics following the WHO ladder from non-opioids such as acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen, to weak opioid such as tramadol or strong opioid such as morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone. The addition of tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, calcium-channel ligands such as gabapentin, and/or less frequently 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as ondansetron seems effective in our experience. Integrative, nonpharmacologic therapies include cognitive behavioral therapy for parents and affected child, aromatherapy, massage, and/or music therapy.

1 Hyams J.S., Burke G., Davis P.M., Rzepski B., Andrulonis P.A. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129(2):220-226.

2 Friedrichsdorf S.J., Brun S., Zernikow B., Dangel T. Palliative Care in Poland: The Warsaw Hospice for Children. Europ J Pall Care. 2006;13(1):35-38.

3 Drake R., Frost J., Collins J.J. The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(1):594-603.

4 Goldman A. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 342(26), 2000. 1998

5 Hongo T., Watanabe C., Okada S., Inoue N., Yajima S., Fujii Y., et al. Analysis of the circumstances at the end of life in children with cancer: symptoms, suffering and acceptance. Pediatr Int. 2003;45(1):60-64.

6 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., Levin S.B., Ellenbogen J.M., Salem-Schatz S., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

7 Wolfe J., Hammel J.F., Edwards K.E., Duncan J., Comeau M., Breyer J., et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717-1723.

8 Lipmann A., Jackson K.II, Tylor L. Evidence based symptom control in palliative care. New York: Pharmaceutical Products Press, 2000.

9 Twycross R., Back I. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Europ J Pall Care. 1998;5(2):39-44.

10 Santucci G., Mack J.W. Common gastrointestinal symptoms in pediatric palliative care: nausea, vomiting, constipation, anorexia, cachexia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):673-689.

11 Ventaffrida V., Oliveri E., Caraceni A., Spoldi E., De Conno F., Saita L., et al. A retrospective study on the use of oral morphine in cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1987;2(2):77-81.

12 Drake R., Longworth J., Collins J.J. Opioid rotation in children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(3):419-422.

13 Maxwell L.G., Kaufmann S.C., Bitzer S., Jackson E.V.Jr, McGready J., Kost-Byerly S., et al. The effects of a small-dose naloxone infusion on opioid-induced side effects and analgesia in children and adolescents treated with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: a double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(4):953-958.

14 Friedrichsdorf S.J., Kuttner L., Westendorp K., McCarty R. Integrative pediatric palliative care. T. Culbert, K. Olness. 2010. Oxford University Press.

15 Lebaron S., Zeltzer L. Behavioral intervention for reducing chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting in adolescents with cancer. J Adolesc Health Care. 1984;5(3):178-182.

16 Cotanch P., Hockenberry M., Herman. Self-hypnosis as antiemetic therapy in children receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1985;12(4):41-46.

17 Hockenberry M.J., Cotanch P.H. Hypnosis as adjuvant antiemetic therapy in childhood cancer. Nurs Clin North Am. 1985;20(1):105-107.

18 Jacknow D.S., Tschann J.M., Link M.P., Boyce W.T. Hypnosis in the prevention of chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting in children: a prospective study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15(4):258-264.

19 Zeltzer L., LeBaron S., Zeltzer P.M. The effectiveness of behavioral intervention for reduction of nausea and vomiting in children and adolescents receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(6):683-690.

20 Vickers A.J. Can acupuncture have specific effects on health? A systematic review of acupuncture antiemesis trials. J R Soc Med. 1996;89(6):303-311.

21 Brock P., Brichard B., Rechnitzer C., Langeveld N.E., Lanning M., Soderhall S., et al. An increased loading dose of ondansetron: a North European, double-blind randomised study in children, comparing 5 mg/m2 with 10 mg/m2. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(10):1744-1748.

22 Stiakaki E., Savvas S., Lydaki E., Bolonaki I., Kouvidi E., Dimitriou H., et al. Ondansetron and tropisetron in the control of nausea and vomiting in children receiving combined cancer chemotherapy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;16(2):101-108.

23 Parker R.I., Prakash D., Mahan R.A., Giugliano D.M., Atlas M.P. Randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous ondansetron for the prevention of intrathecal chemotherapy-induced vomiting in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(9):578-581.

24 Orchard P.J., Rogosheske J., Burns L., Rydholm N., Larson H., DeFor T.E., et al. A prospective randomized trial of the anti-emetic efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron during bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1999;5(6):386-393.

25 Dick G.S., Meller S.T., Pinkerton C.R. Randomised comparison of ondansetron and metoclopramide plus dexamethasone for chemotherapy induced emesis. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73(3):243-245.

26 Koseoglu V., Kurekci A.E., Sarici U., Atay A.A., Ozcan O. Comparison of the efficacy and side-effects of ondansetron and metoclopramide-diphenhydramine administered to control nausea and vomiting in children treated with antineoplastic chemotherapy: a prospective randomized study. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(10):806-810.

27 Uysal K.M., Olgun N., Sarialioglu F. Tropisetron in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced acute emesis in pediatric patients. Turk J Pediatr. 1999;41(2):207-218.

28 Ozkan A., Yildiz I., Yuksel L., Apak H., Celkan T. Tropisetron (Navoban) in the control of nausea and vomiting induced by combined cancer chemotherapy in children. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(2):92-95.

29 Aksoylar S., Akman S.A., Ozgenc F., Kansoy S. Comparison of tropisetron and granisetron in the control of nausea and vomiting in children receiving combined cancer chemotherapy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;18(6):397-406.

30 Klaschik E. Husebø S., Klaschik E., editors. Schmerztherapie und Symptomkontrolle in der Palliativmedizin, ed 3, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer, 2003.

31 Bateman D.N., Rawlins M.D., Simpson J.M. Extrapyramidal reactions with metoclopramide. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291(6500):930-932.

32 Diemunsch P., Apfel C., Gan T.J., Candiotti K., Philip B.K., Chelly J., et al. Preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: post hoc analysis of pooled data from two randomized active-controlled trials of aprepitant. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2559-2565.

33 Diemunsch P., Gan T.J., Philip B.K., Girao M.J., Eberhart L., Irwin M.G., et al. Single-dose aprepitant vs ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial in patients undergoing open abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(2):202-211.

34 Smith A.R., Repka T.L., Weigel B.J. Aprepitant for the control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in adolescents. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45(6):857-860.

35 Gore L., Chawla S., Petrilli A., Hemenway M., Schissel D., Chua V., et al. Aprepitant in adolescent patients for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and tolerability. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(2):242-247.

36 Hall W., Degenhardt L. Medical marijuana initiatives: are they justified? How successful are they likely to be? CNS Drugs. 2003;17(10):689-697.

37 Nocerino E., Amato M., Izzo A.A. Cannabis and cannabinoid receptors. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(Suppl 1):S6-S12.

38 Williamson E.M., Evans F.J. Cannabinoids in clinical practice. Drugs. 2000;60(6):1303-1314.

39 Tramer M.R., Carroll D., Campbell F.A., Reynolds D.J., Moore R.A., McQuay H.J. Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323(7303):16-21.

40 Goldman A., Burne R. Symptom management. In: Goldman A., editor. Care of the dying child. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

41 Riad W., Altaf R., Abdulla A., Oudan H. Effect of midazolam, dexa-methasone and their combination on the prevention of nausea and vomiting following strabismus repair in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2007;24(8):697-701.

42 Ozcan A.A., Gunes Y., Haciyakupoglu G. Using diazepam and atropine before strabismus surgery to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, controlled study. J AAPOS. 2003;7(3):210-212.

43 Kearsley J.H., Williams A.M., Fiumara A.M. Antiemetic superiority of lorazepam over oxazepam and methylprednisolone as premedicants for patients receiving cisplatin-containing chemotherapy. Cancer. 1989;64(8):1595-1599.

44 Bishop J.F., Olver I.N., Wolf M.M., Matthews J.P., Long M., Bingham J., et al. Lorazepam: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study of a new antiemetic in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy and prochlorperazine. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(6):691-695.

45 Gan T.J., Ginsberg B., Grant A.P., Glass P.S. Double-blind, randomized comparison of ondansetron and intraoperative propofol to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1996;85(5):1036-1042.

46 Borgeat A., Wilder-Smith O.H., Saiah M., Rifat K. Subhypnotic doses of propofol possess direct antiemetic properties. Anesth Analg. 1992;74(4):539-541.

47 Krasowski M.D., Hong X., Hopfinger A.J., Harrison N.L. 4D-QSAR analysis of a set of propofol analogues: mapping binding sites for an anesthetic phenol on the GABA(A) receptor. J Med Chem. 2002;45(15):3210-3221.

48 Haeseler G., Karst M., Foadi N., Gudehus S., Roeder A., Hecker H., et al. High-affinity blockade of voltage-operated skeletal muscle and neuronal sodium channels by halogenated propofol analogues. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155(2):265-275.

49 Fowler C.J. Possible involvement of the endocannabinoid system in the actions of three clinically used drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(2):59-61.

50 Lundstrom S., Zachrisson U., Furst C.J. When nothing helps: propofol as sedative and antiemetic in palliative cancer care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(6):570-577.

51 Glover M.L., Kodish E., Reed M.D. Continuous propofol infusion for the relief of treatment-resistant discomfort in a terminally ill pediatric patient with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;18(4):377-380.

52 Hooke M.C., Grund E., Quammen H., Miller B., McCormick P., Bostrom B. Propofol use in pediatric patients with severe cancer pain at the end of life. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24(1):29-34.

53 Beckwith C. Constipation in Palliative Care Patients. In: Lipmann A., Jackson I.IK., Tylor L., editors. Evidence based symptom control in palliative care. New York: Pharmaceutical Products Press; 2000:47-57.

54 Gremse D.A., Hixon J., Crutchfield A. Comparison of polyethylene glycol 3350 and lactulose for treatment of chronic constipation in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2002;41(4):225-229.

55 Pitzalis G., Deganello F., Mariani P., Chiarini-Testa M.B., Virgilii F., Gasparri R., et al. [Lactitol in chronic idiopathic constipation in children]. Pediatr Med Chir. 1995;17(3):223-226.

56 Pashankar D.S., Bishop W.P., Loening-Baucke V. Long-term efficacy of polyethylene glycol 3350 for the treatment of chronic constipation in children with and without encopresis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2003;42(9):815-819.

57 Pashankar D.S., Loening-Baucke V., Bishop W.P. Safety of polyethylene glycol 3350 for the treatment of chronic constipation in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(7):661-664.

58 Tolia V., Lin C.H., Elitsur Y. A prospective randomized study with mineral oil and oral lavage solution for treatment of fecal impaction in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7(5):523-529.

59 Sondheimer J.M., Gervaise E.P. Lubricant versus laxative in the treatment of chronic functional constipation of children: a comparative study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1982;1(2):223-226.

60 Hawley P.H., Byeon J.J. A comparison of sennosides-based bowel protocols with and without docusate in hospitalized patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(4):575-581.

61 Bellomo-Brandao M.A., Collares E.F., da-Costa-Pinto E.A. Use of erythromycin for the treatment of severe chronic constipation in children. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(10):1391-1396.

62 Sykes N. Constipation. In: Doyle D., Hanks G., Cherny N., Calman K., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. ed 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:483-490.

63 Sykes N.P. An investigation of the ability of oral naloxone to correct opioid-related constipation in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 1996;10(2):135-144.

64 Webster L., Jansen J.P., Peppin J., Lasko B., Irving G., Morlion B., et al. Alvimopan, a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor (PAM-OR) antagonist for the treatment of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study in subjects taking opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2008;137(2):428-440.

65 Thomas J., Karver S., Cooney G.A., Chamberlain B.H., Watt C.K., Slatkin N.E., et al. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(22):2332-2343.

66 Driscoll C.E. Symptom control in terminal illness. Prim Care. 1987;14(2):353-363.

67 Beckwith C. Diarrhea in Palliative Care Patients. In: Lipmann A., Jackson I.IK., Tylor L., editors. Evidence based symptom control in palliative care. New York: Pharmaceutical Products Press; 2000:91-108.

68 Friedrichsdorf S., Wamsler C., Zernikow B. Diarrhö. In: Zernikow B., editor. Palliativversongung von Kindern, Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen. Heidelberg: Springer; 2008:169-180.

69 Soares-Weiser K., Goldberg E., Tamimi G., Pitan O.C., Leibovici L. Rotavirus vaccine for preventing diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2004. CD002848

70 Gryboski J.D., Kocoshis S. Effect of bismuth subsalicylate on chronic diarrhea in childhood: a preliminary report. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl 1):S36-S40.

71 Twycross R., Wilcock A. Hospice and Palliative Care Formulary USA, ed 2. Nottingham: Palliativedrugs.com Ltd, 2008.

72 Ghisolfi J., Baudoin C., Charlet J.P., Olives J.P., Ghisolfi A., Thouvenot J.P. [Effects of loperamide on fecal electrolyte excretion in acute diarrhea in infants]. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1987;44(7):483-487.

73 Owens J.R., Broadhead R., Hendrickse R.G., Jaswal O.P., Gangal R.N. Loperamide in the treatment of acute gastroenteritis in early childhood. Report of a two centre, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1981;1(3):135-141.

74 Vesikari T., Isolauri E. A comparative trial of cholestyramine and loperamide for acute diarrhea in infants treated as outpatients. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985;74(5):650-654.

75 Kaplan M.A., Prior M.J., McKonly K.I., DuPont H.L., Temple A.R., Nelson E.B. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a liquid loperamide product versus placebo in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1999;38(10):579-591.

76 Turck D., Berard H., Fretault N., Lecomte J.M. Comparison of racecadotril and loperamide in children with acute diarrhea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Suppl 6;1999: 27-32.

77 Karrar Z.A., Abdulla M.A., Moody J.B., Macfarlane S.B., Al Bwardy M., Hendrickse R.G. Loperamide in acute diarrhea in childhood: results of a double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1987;7(2):122-127.

78 Diarrhoeal Diseases Study Group (UK). Loperamide in acute diarrhea in childhood: results of a double blind, placebo controlled multicentre clinical trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289(6454):1263-1267.

79 Rees H., Markley M.A., Kiely E.M., Pierro A., Pritchard J. Diarrhea after resection of advanced abdominal neuroblastoma: a common management problem. Surgery. 1998;123(5):568-572.

80 Heykants J., Michiels M., Knaeps A., Brugmans J. Loperamide (R 18 553), a novel type of antidiarrheal agent. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1974;24:1649-1653.

81 Litovitz T., Clancy C., Korberly B., Temple A.R., Mann K.V. Surveillance of loperamide ingestions: an analysis of 216 poison center reports. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35(1):11-19.

82 Figueroa-Quintanilla D., Salazar-Lindo E., Sack R.B., Leon-Barua R., Sarabia-Arce S., Campos-Sanchez M., et al. A controlled trial of bismuth subsalicylate in infants with acute watery diarrheal disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(23):1653-1658.

83 Soriano-Brucher H., Avendano P., O’Ryan M., Braun S.D., Manhart M.D., Balm T.K., et al. Bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children: a clinical study. Pediatrics. 1991;87(1):18-27.

84 Gryboski J.D., Hillemeier A.C., Grill B., Kocoshis S. Bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of chronic diarrhea of childhood. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80(11):871-876.

85 Hurwitz E.S., Barrett M.J., Bregman D., Gunn W.J., Pinsky P., Schonberger L.B., et al. Public Health Service study of Reye’s syndrome and medications. Report of the main study. JAMA.. 1987;257(14):1905-1911.

86 Isolauri E., Vahasarja V., Vesikari T. Effect of cholestyramine on acute diarrhea in children receiving rapid oral rehydration and full feedings. Ann Clin Res. 1986;18(2):99-102.

87 Isolauri E., Vesikari T. Oral rehydration, rapid feeding, and cholestyramine for treatment of acute diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4(3):366-374.

88 Bujanover Y., Sullivan P., Liebman W.M., Goodman J., Thaler M.M. Cholestyramine treatment of chronic diarrhea associated with immune deficiency syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1979;18(10):630-633.

89 Coello-Ramirez P. [Cholestyramine in a case of a prolonged diarrhea after a partial ileocolectomy]. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1977;34(2):325-328.

90 Kreutzer E.W., Milligan F.D. Treatment of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis with cholestyramine resin. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1978;143(3):67-72.

91 Liacouras C.A., Piccoli D.A. Whole-bowel irrigation as an adjunct to the treatment of chronic, relapsing Clostridium difficile colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22(3):186-189.

92 Beckman R.A., Siden R., Yanik G.A., Levine J.E. Continuous octreotide infusion for the treatment of secretory diarrhea caused by acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22(4):344-350.

93 Guarino A., Berni Canani R., Spagnuolo M.I., Bisceglia M., Boccia M.C., Rubino A. In vivo and in vitro efficacy of octreotide for treatment of enteric cryptosporidiosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(2):436-441.

94 Lamireau T., Galperine R.I., Ohlbaum P., Demarquez J.L., Vergnes P., Kurzenne Y., et al. Use of a long acting somatostatin analogue in controlling ileostomy diarrhea in infants. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79(8–9):871-872.

95 Smith S.S., Shulman D.I., O’Dorisio T.M., McClenathan D.T., Borger J.A., Bercu B.B., et al. Watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, achlorhydria syndrome in an infant: effect of the long-acting somatostatin analogue SMS 201–995 on the disease and linear growth. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6(5):710-716.

96 Evans W.J., Morley J.E., Argiles J., Bales C., Baracos V., Guttridge D., et al. Cachexia: a new definition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(6):793-799.

97 Goldman A., Hewitt M., Collins G.S., Childs M., Hain R. Symptoms in children/young people with progressive malignant disease: United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group/Paediatric Oncology Nurses Forum survey. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1179-e1186.

98 Inui A. Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome: current issues in research and management. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(2):72-91.

99 Caglar K., Kutluk T., Varan A., Koray Z., Akyuz C., Yalcin B., et al. Leptin and neuropeptide Y plasma levels in children with cancer. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18(5):485-489.

100 Mason P. Anorexia-cachexia: the condition and its causes. Hospital Pharmacist. 2007;14:249-253.

101 Inui A. [Feeding-related disorders in medicine, with special reference to cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome]. Rinsho Byori. 2006;54(10):1044-1051.

102 Kotler D.P. Cachexia. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(8):622-634.

103 Bayram I., Erbey F., Celik N., Nelson J.L., Tanyeli A. The use of a protein and energy dense eicosapentaenoic acid containing supplement for malignancy-related weight loss in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(5):571-574.

104 Dewey A., Baughan C., Dean T., Higgins B., Johnson I. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, an omega-3 fatty acid from fish oils) for the treatment of cancer cachexia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2007. CD004597

105 Tanca F., Madeddu C., Macciò A. New perspective on the nutritional approach to cancer-related anorexia/cachexia: preliminary results of a randomised phase III clinical trial with five different arms of treatment. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2009;2:29-36.

106 Berenstein E.G., Ortiz Z. Megestrol acetate for the treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005. CD004310

107 Azcona C., Castro L., Crespo E., Jimenez M., Sierrasesumaga L. Megestrol acetate therapy for anorexia and weight loss in children with malignant solid tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(4):577-586.

108 Orme L.M., Bond J.D., Humphrey M.S., Zacharin M.R., Downie P.A., Jamsen K.M., et al. Megestrol acetate in pediatric oncology patients may lead to severe, symptomatic adrenal suppression. Cancer. 2003;98(2):397-405.

109 Meacham L.R., Mazewski C., Krawiecki N. Mechanism of transient adrenal insufficiency with megestrol acetate treatment of cachexia in children with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25(5):414-417.

110 Marchand V., Baker S.S., Stark T.J., Baker R.D. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial of megestrol acetate in malnourished children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31(3):264-269.

111 Eubanks V., Koppersmith N., Wooldridge N., Clancy J.P., Lyrene R., Arani R.B., et al. Effects of megestrol acetate on weight gain, body composition, and pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2002;140(4):439-444.

112 Stockheim J.A., Daaboul J.J., Yogev R., Scully S.P., Binns H.J., Chadwick E.G. Adrenal suppression in children with the human immunodeficiency virus treated with megestrol acetate. J Pediatr. 1999;134(3):368-370.

113 Couluris M., Mayer J.L., Freyer D.R., Sandler E., Xu P., Krischer J.P. The effect of cyproheptadine hydrochloride (periactin) and megestrol acetate (megace) on weight in children with cancer/treatment- related cachexia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30(11):791-797.

114 Pinto G., Brauner R., Goulet O., Clapin A., Blanche S. Recombinant human growth hormone therapy for cachexia in HIV infected children. Program Abstr 4th Conf Retrovir Oppor Infect Conf. 1997. p. (abstract 690)

115 UKCCSG-PONF. Mouth care for children and young people with cancer: Evidence-based guidelines. Guideline report version 1.0 February 2006. 2006. Available from: http://www.cclg.org.uk/treatment and research/content.php?3id=28&2id=19 Last accessed June 15, 2010.