Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours

Introduction

In 1907 Oberndorfer first used the name carcinoid to describe rare ileal tumours with less malignant behaviour than common large bowel carcinomas. Subsequently it became a common name for tumours derived from a widely distributed neuroendocrine cell system, and the carcinoids were classified according to embryological origin into foregut carcinoids (lungs, thymus, stomach, duodenum, pancreas), midgut carcinoids (small bowel to proximal colon) and hindgut carcinoids (distal colon and rectum). The new WHO classification from 2010 introduced the term neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) instead of carcinoid. NETs of the gastrointestinal tract (GEP-NETs) are most common (∼ 60%), followed by NETs of the bronchopulmonary system, whereas other locations (ovaries, testes, hepatobiliary system, among others) have been less frequent (Table 6.1).1 GEP-NETs are relatively rare, but had increased in incidence to 6.2 per 100 000 in 2005.2 Since GEP-NETs are overall indolent, their prevalence is high, making them the second most common gastrointestinal (GI) cancer after colon cancer and more prevalent than pancreatic, gastric, oesophageal or hepatic cancer.3

Table 6.1

| Site | Occurrence (%) |

| Extragastrointestinal (lung, thymic, ovary, uterus) |

∼ 30 |

| Oesophagus | < 1 |

| Stomach | 4–8 |

| Duodenum/pancreas | < 2 |

| Small intestine | 25–30 |

| Appendix | 6 |

| Colon | 10 |

| Rectum | 15 |

Many small-intestinal NETs may be clinically silent and subclinical tumours have been detected at autopsy with an incidence of 8%.4 Appendiceal NETs have been commonly found in autopsy studies and previous clinical series, although recent reports indicate an increased proportion of small-intestinal, pulmonary, gastric and rectal NETs, mainly due to increased awareness and improved detection.1,2

The recent WHO classification divides NETs in stages according to proliferation rates determined by Ki67/Mib-1 antibody staining (against proliferation antigen) and mitotic index (number of mitoses per 2 mm2 or 10 high-power fields) (Box 6.1).5–9 Grade 1 tumours have a low rate of mitosis and low proliferation rate, Ki67 index ≤ 3%, Grade 2 tumours have Ki67 index 3–20% and Grade 3 tumours Ki67 index > 20%.5–9 The most poorly differentiated grade 3 tumours, neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), have increased rates of mitoses and higher proliferation index of ≥ 20–40%. The Ki67 proliferation index has become of increased importance in clinical planning. Extensive surgery is more likely to be beneficial for differentiated tumours with low proliferation, in contrast to chemotherapy, which generally has little effect in low proliferating, typicallly small-intestinal NETs.

Chromogranin A and synaptophysin immunostains, which identify proteins of neurosecretory granules, are commonly used to identify NETs. Antibodies against cytosolic markers – neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and PGP9.5 – have also been used for identification of certain tumours, but have generally not been as specific.10 For poorly differentiated lesions chromogranin staining may be variable and involve only subsets of cells. Synaptophysin reactivity alone, in the absence of chromogranin staining, may indicate an exocrine tumour with endocrine differentiation, or a so-called mixed exocrine–endocrine carcinoma. Dominant secretion (e.g. serotonin, histamine, gastrin, somatostatin) may also be detected in NETs, and occasionally ectopic hormone production is seen, such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). The latter two sometimes cause an ectopic Cushing’s syndrome in association with NETs (Table 6.2).10

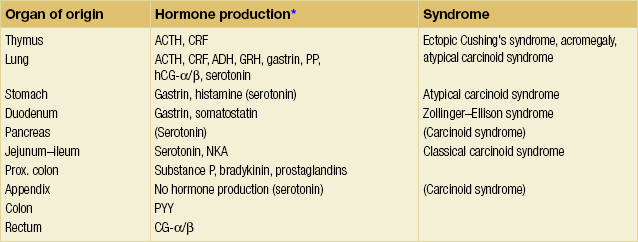

Table 6.2

Classification of NETs, hormone production and syndromes7

*ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH, antidiuretic hormone (vasopressin); CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; GRH, growth hormone; hCG, human choriogonadotropin (α/β subunits); NKA, neurokinin A; PP, pancreatic polypeptide; PYY, peptide YY.

Oesophageal NETs

Oesophageal NETs are exceedingly rare, and occur with male predominance at an age of around 60 years.11 Most tumours are found in the lower third of the oesophagus or in the gastro-oesophageal junction. Symptoms are non-specific and similar to adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, and patients rarely exhibit a carcinoid syndrome. Lymph node metastases have been present at diagnosis in 50% of patients; survival correlates with stage of the disease and overall is poor.

Gastric NETs

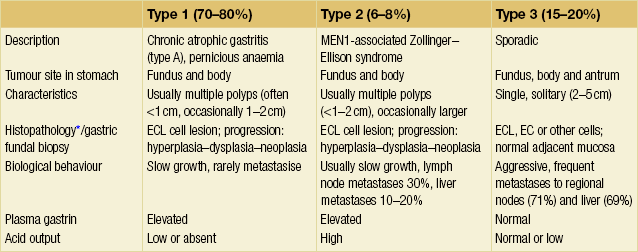

Gastric NETs are rare tumours, constituting less than 1% of gastric neoplasms and approximately 8% of all GEP-NETs (Table 6.1).1,11 Most of these tumours are derived from enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells of the gastric fundus and corpus. The tumours are immunoreactive to chromogranin A, synaptophysin and histamine, and can be identified with the specific marker vesicular monoamine transporter isoform 2 (VMAT2).12 The majority of gastric NETs occur secondary to hypergastrinaemia in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) (type 1 gastric NETs). These NETs are typically multicentric and develop concomitant with ECL cell hyperplasia in the fundus and corpus, or occasionally in the transitional zone to the antrum.13 Similar non-antral and multicentric NETs and ECL cell hyperplasia have less frequently been diagnosed in patients with hypergastrinaemia and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)-related Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES) (type 2 gastric NETs). Both type 1 and 2 gastric NETs develop from ECL cell hyperplasia in a stepwise progression through dysplasia to formation of carcinoid NETs.13–15

The incidence of gastric NETs has increased, due to more frequent gastroscopic examinations, such as during population screening for gastric cancer, or when screening studies have been performed in patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anaemia.13

Type 1: gastric NETs associated with chronic atrophic gastritis

These tumours account for 70–80% of gastric NETs11 (Table 6.3). They occur occasionally in young individuals, but most commonly in older patients, with a mean age around 65 years, and there is a 3:1 female to male predominance.15

These NETs develop in patients with autoimmune CAG type A,13,16 where atrophy of the fundic mucosa is accompanied by pentagastrin-resistant achlorhydria and vitamin B12 malabsorption. More than half of the patients also have pernicious anaemia (Table 6.3). Reduction of gastric acid and increase in pH stimulates gastrin secretion from gastrin (G) cells in the antrum, and the resulting hypergastrinaemia induces hyperplasia of the fundic ECL cells. Diffuse argyrophilic hyperplasia of the non-antral mucosa occurs in 65% of patients with CAG and micronodular/adenomatoid hyperplasia in 30%, whereas the precarcinoid and dysplastic, enlarged micronodules develop mainly in patients with gross NETs. The tumour development progresses from the specified stages of hyperplasia, through dysplastic stages, to neoplastic intramucosal or invasive NETs.14

The type 1 gastric NETs are predominantly located within the body or the fundus of the stomach or in the transitional zone to the antrum.16,17 They are frequently multicentric, consisting of multiple, small gastric polyps and invariably associated with ECL cell hyperplasia and microscopic tumours. The number of gross lesions can, however, be limited and some tumours may thus appear as solitary. Individual tumours can present as broad-based, round polypoid lesions, reddish to yellowish, depending on the thickness of the covering mucosa. Some lesions can be flat and broad, or appear as discoloured spots or simply as slight mucosal protrusions. Only a few are ulcerated or bleeding. The number and size vary from innumerable pinpoint-sized tumours to a few or solitary prominent lesions ranging from a few millimetres up to 1–1.5 cm, and only occasionally larger tumours (> 2 cm). The polypoid NETs may be difficult to distinguish from hyperplastic polyps, which are also more frequent in patients with CAG.

Small type 1 gastric NETs are almost always benign with low risk of invasion beyond the submucosa. Larger lesions (> 1 cm) are also predominantly benign but may rarely have invasion of the muscularis propria (< 10%).15 CAG-associated NETs have a lower incidence of metastases and more favourable outcome than other types of gastric NETs. Metastases to regional lymph nodes occur in 5% and distant metastases in around 2%.9,15,18 However, earlier reports with a greater proportion of large lesions described more frequent metastases.19 Disease-related deaths are exceptional.

Type 2: NETs associated with ZES in MEN1 patients

These gastric NETs constitute 6–8% of all gastric NETs,11 and are thus much less common than those associated with atrophic gastritis (Table 6.3). They occur in patients with MEN1 and gastrin-producing tumours as a cause of ZES, with equal female:male distribution, at a mean age of 45–50 years.16

ECL cell hyperplasia is found in almost 80% of MEN1 patients with ZES, and fundic gastric NETs develop in up to 5–30% of these patients.15,20 In addition to the hyperplasia and dysplasia of ECL cells in the fundic mucosa, the oxyntic mucosal thickness is invariably increased, in contrast to the atrophy of type 1 lesions. These NETs also develop in a hyperplasia–dysplasia–neoplasia sequence, but have mainly been associated with diffuse hyperplasia, and less evident micronodular changes. However, gastric NETs in sporadic ZES are rare, and virtually only ZES in association with MEN1 seems to promote growth of gastric NETs.21 The MEN1 syndrome is caused by an inherited mutation of the MEN1 tumour suppressor gene located on chromosome 11q13.22 As in other MEN1 lesions, the gastric NETs in MEN1 lose their single remaining functional copy of the MEN1 gene by chromosomal deletions.23 In MEN1 patients without ZES, gastric NETs are extremely rare.24 Thus, hypergastrinaemia seems to be required for development of gastric NETs from ECL cell hyperplasia. However, additional factors are obviously needed for tumour formation, since only 1% of patients with hypergastrinaemia due to atrophic gastritis and < 1% of patients with sporadic ZES develop gastric NETs.20,24,25

The type 2 gastric NETs are located in the gastric body and fundus, and occasionally in the antrum, and are composed mainly of ECL cells with sparse other cell types. They are most often multiple and small (73% are smaller than 1.5 cm), although often larger than type 1 tumours, with a size varying from 0.5 to 2 cm. Occasionally, there are markedly larger tumours.13 The malignant potential is intermediate between that of CAG-associated gastric NETs and sporadic NETs, and 90% will not have infiltrated beyond the submucosa. However, lymph node metastases are present in up to 30% of the patients, and distant metastases, assumed to originate from gastric NETs, occur in 10–20%.15 MEN1 patients develop distant metastases from other MEN1-associated tumours as well, and the gastric NETs are not the most likely origin. The overall prognosis will depend more on the other MEN1 lesions, and the prognosis is usually rather favourable for the type 2 NETs.21 However, rare cases of highly malignant neuroendocrine gastric carcinomas with poor prognosis have also occurred in some MEN1/ZES patients.24

Type 3: sporadic gastric NETs

Tumours with no association to hypergastrinaemia account for 15–20% of the gastric NETs and have features that markedly differ from type 1 and type 2 lesions (Table 6.3).16 They occur sporadically, are usually solitary, and grow much more aggressively. Many are already disseminated at diagnosis.16 These NETs have a male predominance, with a male:female ratio of 3:1; mean age of presentation is reportedly around 50 years. The sporadic gastric NETs occur in non-atrophic gastric mucosa, without endocrine cell proliferation. Determination of serum calcium and examination of the family history may help exclude the MEN1 syndrome, which should be suspected in all patients with foregut NETs unrelated to atrophic gastritis.

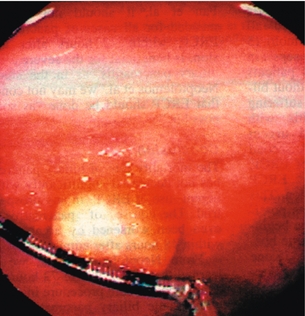

The sporadic tumours are often large; 70% are > 1 cm with a mean size of 3.2 cm (Fig. 6.1).15,16 Two-thirds of the lesions will have infiltrated the muscularis propria and 50% invaded all layers of the gastric wall.15 Some tumours occur in the antral, prepyloric regions, although the majority are located in the body and fundus of the stomach. Most tumours originate in argyrophilic ECL cells, but a mixture of other cell types and EC cells may be present, and are associated with a less favourable prognosis. Regional lymph node metastases have been described in 71% of the patients, and liver metastases have ultimately developed in 69% of the patients. Half of patients are alive after follow-up of 5 years, but patients with distant metastases have a 10% 5-year survival.1,15,26

The sporadic NETs are generally well differentiated, but often of grade 2 with Ki67 index > 2%. According to previous classification they may have typical or atypical histology, where atypical implies marked nuclear pleomorphism, increased number of mitoses, and areas of necrosis. The atypical tumours are larger, more frequently invasive and commonly associated with metastases at diagnosis.9 A series of sporadic gastric NETs with atypical morphology reported a mean size of 5 cm and unfavourable survival.27

An atypical carcinoid syndrome has developed in 5–10% of the patients with sporadic gastric NETs and is associated with tumour release of histamine. The syndrome is characterised by bright red cutaneous flushing, often with a patchy ‘geographic’ distribution, cutaneous oedema, intense itching, bronchospasm, salivary gland swelling and lacrimation.11,16 The atypical carcinoid syndrome is related to histamine secretion, and urinary estimates of the histamine metabolite methylmidazole-acetic acid (MelmAA) may serve as a tumour marker. Most gastric NETs are deficient in the enzyme L-amino acid decarboxylase, and only a few patients have elevated levels of serotonin. Urinary excretion of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) is therefore less appropriate as a tumour marker.17 However, the precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) may be excreted and partly decarboxylated in the kidney, and patients with disseminated sporadic gastric NETs may exhibit some elevated urinary 5-HIAA values.

Gastrinoma

Tumours with sparse staining for gastrin may occur in association with chronic atrophic gastritis. Tumours with intense positive staining for gastrin are rare in the stomach, and are more commonly located in the prepyloric mucosa close to the duodenum. Few gastric NETs cause hypergastrinaemia and peptic ulcer disease, but they still represent an exceptional but possible origin of gastrin excess and ZES.17 Rare tumours may present with ectopic Cushing’s syndrome due to ACTH secretion.

Poorly differentiated gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas

The poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) are highly malignant neoplasms, with generally extensive local invasion and metastases already at diagnosis. They are not associated with the carcinoid syndrome and occur at a mean age of 60–70 years, with male predominance.15,28 Atrophic gastritis has been revealed in half of the patients, but is not believed to cause the tumour, since only a minority of patients have hypergastrinaemia.15 The majority of tumours are located in the gastric corpus or fundus, but 10–20% may occur in the antrum.15,28 The tumours are generally large, with median size of around 4–5 cm,13 invariably deeply invading the gastric wall and associated with metastases. The majority of lesions appear as ulcerated tumours and a quarter are fungating.28 They all tend to be of histological grade 3, and often have solid structures with necrosis, a high degree of atypia, frequent mitoses and high proliferation index in Ki67 staining (generally around 20–40%). Almost all tumours show vascular and perineural invasion. In contrast to the well-differentiated gastric NETs, the poorly differentiated NECs may have sparse immunoreactivity to chromogranin A, at least in the majority of tumour cells.9 Immunoreactivity to synaptophysin (and possibly NSE or PGP9.5) may verify the neuroendocrine differentiation and separate these tumours from exocrine carcinomas. The prognosis is poor with a median survival of 8 months, albeit some individuals are reported to be still alive after follow-up of 10–15 years.9,15,28

The possibility of progression from well-differentiated gastric NETs, especially type 3 lesions, to NECs has been suggested by a few cases with coexisting well and poorly differentiated gastric NETs.9,24

Aberration of the p53 tumour suppressor gene and chromosomal deletion of the long arm of chromosome 18 are common in poorly differentiated NECs, and occasionally found also in type 3 sporadic gastric NETs.9 These genetic defects occur in gastrointestinal exocrine carcinomas and may promote aggressive tumour growth. Genetic studies of rare mixed neuroendocrine/exocrine gastric carcinomas indicate that the endocrine tumour component may originate in adenocarcinoma cells.29

Clinical evaluation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CAG type 1 NETs is based on demonstration of high levels of serum gastrin, lack of gastric acid secretion and demonstration of atrophy of the oxyntic mucosa, with concomitant ECL cell hyperplasia in mucosal biopsies from the fundus (Table 6.3). The serum levels of gastrin are also high in patients with MEN1 gastrinomas, although these patients have contrasting high gastric acidity.

Thorough gastroscopic examination should be performed to evaluate multiplicity and size of the gastric NETs. Tumour biopsies should be stained with specific endocrine tumour markers and proliferation markers (chromogranin A, Ki67 staining), and should carefully investigate infiltrative depth and possible vascular invasion. In addition, biopsy samples should be taken from antrum (two biopsies) and fundus (four biopsies) to reveal concomitant ECL cell hyperplasia or dysplasia, the presence of atrophic gastritis, or the contrasting increased oxyntic mucosa thickness of rare MEN1/ZES (Table 6.3).30,31 Multiple NET polyps in the gastric fundus in an elderly individual are most likely to represent CAG-associated NETs, since MEN1-associated NETs are rare. A larger, solitary tumour is more likely to be sporadic (Fig. 6.1), and the largest ulcerating and most prominent lesions may be poorly differentiated. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) should be added to the gastroscopic examination in type 1 and 2 lesions of size > 1 cm and all type 3 lesions to give information about infiltrative depth.30,32 EUS may also reveal associated lesions in the pancreas or duodenum in MEN1 patients, and possibly also show metastases to regional lymph nodes or the liver.32

Biochemical screening for other MEN1 endocrinopathies should include analysis of serum calcium and parathyroid hormone, pituitary-related hormones such as growth hormone, prolactin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and pancreatic hormones (Box 6.2). For cases with the atypical carcinoid syndrome, screening should include urinary analysis of the histamine metabolite MelmAA.13 Serum values of chromogranin A are generally raised in patients with CAG and ECL cell hyperplasia. These values are also the most important tumour markers, and since they tend to reflect the tumour load, they are often used to monitor patients undergoing treatment for advanced gastric NETs.33

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast enhancement is routinely performed for tumour delineation and to detect regional lymph node or liver metastases. Scintigraphy using [111In]octreotide scintigraphy (OctreoScan) can often efficiently reveal metastatic spread from differentiated NETs.30,31,34

Treatment

CAG-associated type 1 gastric NETs

These may disappear spontaneously, and few show more marked progression. Small, multicentric lesions may be followed with annual repeated endoscopy.17,25,30,31,35,36

Antrectomy has been recommended for treatment of CAG-associated gastric NETs, with the aim of inhibiting antral overproduction of gastrin.40,41 The antrectomy is claimed to cause regression of ECL cell dysplasia and small NETs; however, large, invasive or metastatic lesions may remain unaffected.40–42 Resection of the antrum may therefore be considered for multicentric or recurrent tumour, and is often combined with surgical excision of larger type 1 NETs, but results and morbidity of this versus repeated endoscopic excision remain unclear.26,30,42

Sporadic type 3 gastric NETs

In cases with metastases, tumour debulking of lymph gland and liver metastases may alleviate symptoms of an associated carcinoid syndrome and apparently improve survival.16 Hepatic metastases may be treated with liver resection, hepatic artery embolisation or chemoembolisation, and radiofrequency (RF) ablation (see below).31 The somatostatin analogue octreotide may palliate symptoms in patients with the carcinoid syndrome. Chemotherapy is likely to be valuable when the proliferation index exceeds 5% and has response rates of 20–40%. Chemotherapy can be combined with other treatment modalities.31,46

Poorly differentiated NECs

These generally have a dismal prognosis, with a median survival of only 8 months.9,15,30,39 The tumours are rarely suitable for radical surgery and recurrence should be checked for after gastric resection. However, aggressive surgery together with chemotherapy may be an option to consider, especially in patients with mixtures of well and poorly differentiated tumours.9

Duodenal NETs

NETs of the duodenum are rare, and comprise less than 2% of all gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours.17,47 Duodenal adenomas or adenocarcinomas are much more frequent. However, the endocrine tumours are important to recognise because of a possible association with hormonal or hereditary syndromes and the consequential requirements of treatment. Duodenal NETs are so rare that it is difficult to identify prognostic factors and decide optimal treatment on an evidence base.

Gastrinomas

Gastrin-cell (G-cell) tumours – gastrinomas – are the most prevalent and constitute 60% of the duodenal neuroendocrine tumours; 15–30% of G-cell tumours cause clinical ZES, the remainder are clinically silent.17,47 Most gastrinomas are located in the first and second parts of the duodenum. They are frequently small (often around 0.5 cm or smaller), with early metastases to regional lymph nodes reported in 30–70% of patients.15,48–51 The regional lymph node metastases may be considerably larger than the primary tumours, which sometimes may be difficult to detect even at operation. There is generally considerable delay before liver metastases develop, and this is claimed to provide a favourable interval for surgical treatment.50 It has been recognised that 40–60% of gastrinomas responsible for ZES are located within the duodenal submucosa.48,49 MEN1/ZES patients have, in nearly 90% of cases, multifocal duodenal gastrinomas.48,49 The duodenal gastrinomas in ZES are slow-growing, indolent malignancies despite their tendency to spread with local lymph node metastases. Duodenal gastrinomas in ZES are rarely identified by endoscopy because of their small size, and they are also often difficult to visualise during surgery. Endoscopic transillumination has been advocated, but it is more efficient to perform a long duodenotomy, allowing discovery of gastrinomas after inversion and palpation of the duodenal mucosa.48,52

Somatostatin-rich NETs

NETs with somatostatin reactivity comprise 15–20% of duodenal neuroendocrine tumours. These tumours are most often clinically hormonally non-functioning.47,54,55 They occur almost exclusively in the ampulla of Vater, causing obstructive jaundice, pancreatitis or bleeding. The tumours appear as 1- to 2-cm homogeneous ampulla nodules, which only occasionally are polypoid, larger or ulcerated. Regional lymph node or liver metastases are present in nearly 50% of patients. Unlike conventional NETs, these tumours have a glandular growth pattern and characteristically contain special laminated psammoma bodies. They can be identified with chromogranin stain. One-third of these lesions are associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis (neurofibromatosis type 1, NF1) and occasionally with phaeochromocytoma.56 Depending on the size of the tumours and the age of the patient, the somatostatin-rich NETs may be locally excised or removed by pancreatico-duodenectomy.

Gangliocytic paragangliomas

Gangliocytic paragangliomas are rare tumours, occurring almost exclusively in the second portion of the duodenum, and are sometimes associated with neurofibromatosis (NF1).57 The tumours consist of a mixture of paraganglioma, ganglioneuroma and NET tissue with reactivity for somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide (PP). The tumours are generally benign, recognised only incidentally or because of bleeding, and have an excellent prognosis following surgical excision.

Other duodenal NETs

More unusual well-differentiated duodenal NETs may display reactivity for other hormones, such as calcitonin, PP and serotonin.57 Most of these tumours are found in the proximal part of the duodenum as small polyps (< 2 cm). Multiple tumours should raise suspicion of an associated MEN1 syndrome. The majority of these tumours are low-grade malignant and often suitable for local surgical excision.58 Only rarely do large tumours require pancreatico-duodenectomy.

A distinct group of duodenal NETs without release or staining for hormones is also recognised. These tumours have a somewhat different biology and metastasise less often than the gastrinomas and somatostatinomas.57 Some of them are asymptomatic and are found incidentally on endoscopic examination. Others present with non-specific abdominal symptoms, gastrointestinal bleeding and sometimes with vomiting or weight loss.57 Most tumours are located in the first portion of the duodenum, occasionally in the second part and rarely in the third portion (horizontal duodenum). The majority stain for chromogranin A, and some for synaptophysin and/or NSE.57 Up to one-third of the patients have had other primary malignancies as well, including adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, prostate or other organs.59

More than half of the tumours are smaller than 2 cm and generally have a good prognosis after resection. Size > 2 cm, invasion beyond the submucosa or presence of mitotic figures are independent risk factors for metastases.47 Tumours with these risk factors are also likely to recur after apparently curative surgery, even if no lymph node metastases have been detected, whereas lesions smaller than 2 cm rarely metastasise.58

Lesions smaller than 1 cm can possibly be endoscopically excised, but re-examination with follow-up endoscopy is required to ensure complete removal.58 Tumours smaller than 2 cm, without signs of invasion of the muscularis, can be treated by open local excision. The treatment suggested for larger tumours is segmental resection or pancreatico-duodenectomy in order to decrease the risk of recurrence.58 Periampullary tumours behave in a malignant fashion and need more radical surgery. Patients with metastasising duodenal NETs may survive for decades, substantiating that these NETs are less aggressive than adenocarcinomas.

Pancreatic NETs

Pancreatic islet cell tumours are generally classified according to their dominant hormone secretion, or depicted as clinically non-functioning if not associated with any clinical syndrome of hormone excess. Exceptionally, endocrine tumours of the pancreas stain intensely for serotonin (and may also contain other biogenic amines).17,59 They appear histologically as classical GEP-NETs, but few have been associated with the carcinoid syndrome. The tumours are managed surgically according to guidelines similar to those for other malignant endocrine pancreatic tumours. Hepatic metastases and a carcinoid syndrome may be treated with somatostatin analogues and interferon, or chemotherapy in the presence of a higher proliferation rate.

Jejuno-ileal (small-intestinal) NETs (midgut carcinoids)

The jejuno-ileal NETs originate from intestinal enterochromaffin (EC) cells in intestinal crypts. They have been named ‘classical’ midgut carcinoids, and typically display serotonin immunoreactivity in the tumour cells.60 The small-intestinal NETs have increased in frequency, and constitute ∼ 30% of GEP-NETs.1,11,60 Being the most common cause of the carcinoid syndrome, these tumours have often prevailed at referral centres, since this syndrome has required somewhat complicated and often combined medical and surgical treatment.11,60 The small-intestinal NETs account for 25% of small-bowel neoplasms and have been diagnosed at an average age of 65 years, with slight male predominance.

Morphological features

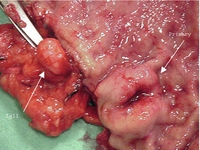

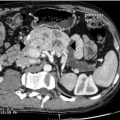

The primary small-intestinal NET is most commonly located in the terminal parts of the ileum, often appearing as a small, flat and fibrotic submucosal tumour, measuring around 1 cm or less (Fig. 6.2),60,61 occasionally with some central navelling. Sometimes the tumour is so tiny that it is difficult to detect at surgery, appearing only as a limited area of fibrosis or circumscribed thickening of the intestinal wall. In up to one-third of patients, multiple smaller neuroendocrine polyps occur in the nearby intestine, most likely caused by lymphatic dissemination.61 In a few cases additional larger neuroendocrine polyps have been found in proximal parts of the intestine, and may appear to represent additional primary tumours. Among patients subjected to surgery, the incidence of mesenteric metastases has been as high as 70–90%, irrespective of tumour size. When growing close to the intestinal wall such metastases have sometimes been mistaken for primary tumours. In contrast to NETs located elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, microscopic or gross metastases have also occurred in association with the smallest primary tumours.61 Unusual large primary tumours sometimes extend directly into a conglomerate of mesenteric lymph gland metastases. The mesenteric metastases typically grow conspicuously larger than the primary tumour, and characteristically evoke a marked desmoplastic reaction with pronounced mesenteric fibrosis61 (Fig. 6.3). The fibrosis might result from local effects of serotonin, growth factors and other substances secreted from the neuroendocrine metastases.60,62

Figure 6.2 Small-intestinal NET, unusual entity with liver metastases but no mesenteric tumour. Reproduced from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

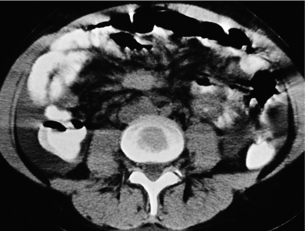

Figure 6.3 Computed tomography image of mesenteric metastasis from a small-intestinal NET, typically surrounded by fibrosis (appearing like ‘hurricane centre’). Reproduced from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

With more extensive fibrosis the distal ileal mesentery often becomes contracted and tethers the mesenteric root to the retroperitoneum, with fibrous bands attaching to the serosa of the horizontal duodenum. Occasionally, fibrosis and tumour extend over parts of the transverse or the sigmoid colon.61

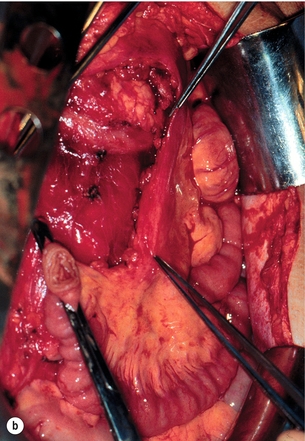

The mesenteric tumour and fibrosis can often cause partial or complete small-intestinal obstruction by kinking and fibrotic entrapment of the intestine, whereas the primary tumour is only occasionally large enough to obstruct the intestinal lumen.61 Obstruction of the duodenum tends to occur at advanced stages. The mesenteric vessels are often encased or occluded by the growing mesenteric tumour, with resulting local venous stasis and ischaemia in the small intestine, and occasionally frank impairment of the intestinal circulation. Variable segments of the small intestine thus appear dark blue to reddish due to incipient venous gangrene (Fig. 6.4), or occasionally pale and cyanotic due to deficient arterial circulation.60,61 A specific angiopathy, called vascular elastosis, occurs with advanced small-intestinal NETs and causes marked thickening of mesenteric vessel walls due to elastic tissue proliferation in the adventitia; this contributes to the intestinal vascular impairment.63 However, compression by tumour and fibrosis has in our experience been the obvious cause in patients where intestinal ischaemia was revealed at operation.60,61

Figure 6.4 Intestinal venous ischaemia due to small-intestinal NET. Reproduced from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Distant metastases from small-intestinal NETs occur most commonly in the liver and the patients then often present with variable features of the carcinoid syndrome. Liver metastases are often bilateral and diffusely spread; approximately 10% of patients have fewer or dominant lesions, sometimes with conspicuous growth of individual lesions. Around 10% of patients present with liver metastases, without mesenteric lesions. Spread to extra-abdominal sites can involve the skeleton (spine and orbital framing are predilection sites), the lungs, CNS, mediastinal and peripheral lymph nodes, ovaries, breast and the skin.60 A neck lymph gland metastasis can sometimes be the primary clinical sign of a disseminated tumour.

Clinical symptoms

The small-intestinal NETs grow slowly and many patients have experienced long periods of prodromal symptoms before the disease has been clinically recognised.60,61 Some patients have had symptoms of borborygmi or episodic abdominal pain, others have had unrecognised features of the carcinoid syndrome, with diarrhoea, discrete flush, palpitations or intolerance for specific food or alcohol. Intestinal bleeding is generally rare with small-intestinal NETs due to the moderate size and submucosal location of the primary tumour. Bleeding has been mainly encountered at later stages, with larger, ulcerating primary tumours, or if mesenteric metastases have grown in the intestinal wall.61,62 Such metastases have a special tendency to grow into the horizontal duodenum and sometimes cause bleeding. In other cases bleeding has occurred as a result of intestinal venous stasis.

Intermittent attacks of abdominal pain may initially occur, and increase in frequency until the patient develops obvious subacute or acute intestinal obstruction requiring surgery. In 30–45% of patients the small-intestinal NETs are thus revealed at operation for intestinal obstruction, where the patients often have been submitted to surgery without awareness of the diagnosis.62 In another 50% of patients the diagnosis becomes evident after detection of liver metastases, and some of the patients initially appear with features of the carcinoid syndrome.

Carcinoid syndrome

The carcinoid syndrome occurs in approximately 20% of patients with jejuno-ileal NETs.1,11,60 Monoamine oxidase activity in the liver can generally detoxify substances released from the intestinal and mesenteric tumours, and symptoms associated with the carcinoid syndrome generally imply that the patient has liver metastases. Occasionally the syndrome may be encountered in patients with large retroperitoneal or ovarian lesions, where secretory products exceed the capacity of detoxification or can bypass the liver and drain directly into the systemic circulation. The syndrome includes flushing, diarrhoea, right-sided valvular heart disease and bronchoconstriction. The aetiology of the carcinoid syndrome is related to release of serotonin, bradykinin, tachykinins (substance P, neuropeptide K), prostaglandins and growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), as well as occasionally noradrenaline (norepinephrine).64

Secretory diarrhoea is the most common feature of the syndrome, but it may sometimes be mild and non-specific initially. Diarrhoea is often most prevalent in the morning and often meal related. The diarrhoea may, however, have many causes in NET patients, especially when they have been previously operated upon or have reached advanced disease stages.60 Resection of the distal small intestine may cause moderate diarrhoea due to reduced bile salt absorption; other causes are a short bowel or partial intestinal obstruction. In patients with large mesenteric tumours intestinal venous stasis or ischaemia may often contribute significantly to stool frequency. Severe watery diarrhoea and malnutrition can occasionally occur due to occlusion of main mesenteric veins, which can cause severely oedematous, fluid-leaking intestinal segments of variable length.60,61,65

Heart valve fibrosis, affecting tricuspid and pulmonary valves with plaque-like fibrotic endocardial thickening, is a serious and late consequence of a severe and long-standing carcinoid syndrome.60,66,67 Serotonin and tachykinins may influence the heart and cause fibrosis and valvular thickening with retraction and fixation of the heart valves and subsequently regurgitation and stenosis. As many as 65% of patients with the carcinoid syndrome have tricuspid valve abnormalities, and 19% had pulmonary valve regurgitation in one series.66 In less than 10%, the pulmonary degradation by monoamine oxidase activity is exceeded and the fibrosis may also involve the left-sided heart valves, and possibly contribute to bronchoconstriction.

The carcinoid heart disease may cause progressive cardiac insufficiency with typically right-sided heart failure and severe lethargy, and used to be an important cause of death in patients with the carcinoid syndrome.66,67 However, nowadays, after introduction of somatostatin analogues, patients more often die of progressive tumour disease.10 Affected patients may require heart surgery and replacement of fibrotic heart valves with prostheses.67 This operation may lead to substantial improvement, but can be associated with complications, especially in older persons. The heart disease can be diagnosed by echocardiography, which should always be performed prior to major abdominal surgery.

Bronchial constriction as part of the carcinoid syndrome caused by small-intestinal NETs is rare.

Diagnosis

The biochemical diagnosis of small-intestinal NETs is often based on the demonstration of raised concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA excreted in 24-hour urine samples. The raised 5-HIAA values are specific for small-intestinal NETs, but occur only at advanced disease stages and generally imply the presence of liver metastases.10,60

Determination of plasma chromogranin A is a more sensitive measure, which may be used for the early diagnosis of persistent or recurrent small-intestinal NET disease. Circulating chromogranin A levels reflect the tumour load, and serial measurements have become the most important parameter for monitoring disease spread and to follow results of treatment.10,61 The chromogranin values may also predict prognosis. However, it is a non-specific marker for any NET, and false-positive values occur with liver or kidney failure, inflammatory bowel disease, atrophic gastritis or chronic use of proton-pump inhibitors.

Human choriogonadotropin α and β subunits (hCG-α/β) may be predictors of poor prognosis.10 Exceptionally, NETs secrete enteroglucagon and PP, but PP is a non-specific marker, which may be raised in any patients with diarrhoea.10

Radiology

The primary small-intestinal NETs are generally too small to be diagnosed with conventional bowel contrast studies.10,60 At more advanced disease stages, typical arcading of entrapped intestines with segments of partial obstruction may be visualised, and occasionally signs of chronic obstruction, with thickened bowel wall. In patients with large-bowel symptoms entrapment of the sigmoid or transverse colon may be important to identify prior to surgery. Concomitant colorectal adenocarcinoma has been reported in 10–15%, and it may sometimes be necessary to exclude coexisting rectosigmoidal adenocarcinoma by endoscopy, prior to surgery or during follow-up of a small-intestinal NET.

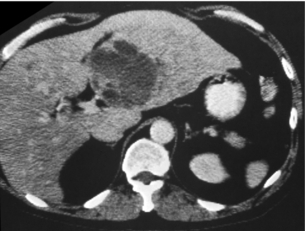

Computed tomography: CT can very infrequently visualise a primary small-intestinal NET, but often efficiently demonstrates mesenteric lymph node metastases, retroperitoneal extension of such masses, and liver metastases. The presence of a circumscribed mesenteric mass with radiating densities is very suspicious of a small-intestinal NET with mesenteric metastasis60 (Fig. 6.3).

Ultrasound: Percutaneous ultrasound is mainly utilised to visualise liver metastases or to guide semi-fine-needle biopsy for histological diagnosis of liver metastases or the deposits in the mesentery. Ultrasound with power Doppler enhancement, and especially use of ultrasound contrast, may increase sensitivity for detection of liver metastases.

OctreoScan®: In nearly 90% of cases, small-intestinal NETs possess somatostatin receptors types 2 and 5, for which the somatostatin analogue octreotide has high affinity.10 Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (OctreoScan®) has detected small-intestinal NETs with a sensitivity of 90% and is being increasingly utilised to determine metastatic spread. OctreoScan® is especially efficient for detection of extra-abdominal metastases and can visualise bone metastases better than a routine isotope bone scan, which may miss especially osteolytic metastases.

Positron emission tomography (PET): PET with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan, labelled with 11C (5-HTP-PET), or gallium-68 (68 Ga) PET can identify the small-intestinal NETs with high sensitivity, and has been used to monitor effects of therapy.68,69 PET with [18 F]deoxyglucose (FDG) is rarely positive in low proliferating small-intestinal NETs and positivity indicates highly aggressive lesions.

Histology

Needle biopsy specimens from metastases are often used for diagnosis. The NET cells stain immunocytochemically with neuroendocrine tumour markers, mainly chromogranin A and synaptophysin. Reactivity with serotonin-specific antisera implies that a primary tumour should be searched for in the midgut;10,60 85% of jejuno-ileal NETs show reactivity for chromogranin A and serotonin.10 Proliferation rate is determined with the Ki67 antibody and is most often low in classical small-intestinal NETs (often < 2%).46

Most jejuno-ileal NETs show a mixed insular and glandular growth pattern; occasional tumours have a pure insular and trabecular pattern and have been reported as having a slightly less favourable prognosis.11 Occasional tumours have a higher proliferation rate initially, or during the disease course, and very rarely a lesion may present as an NEC with undifferentiated pattern and very high proliferation rate, with poor prognosis and with sparse effect of surgery.

Surgery

Many patients with small-intestinal NETs will be subjected to acute laparotomy due to intestinal obstruction without suspicion of the correct diagnosis. It is important to appreciate then that the NET is common among small-bowel neoplasms, and findings at laparotomy are often typical with a tiny ileal primary tumour, and conspicuously larger mesenteric metastases with marked mesenteric desmoplastic reaction.60,61,70–73 The primary tumour and mesenteric metastases should be removed by wedge resection of the mesentery and limited intestinal resection, and lymph node metastases should be cleared as far as possible by dissection around the mesenteric artery and vein and their branches.71 This procedure is generally indicated even in the presence of liver metastases. If the surgery has been inadequately performed, because the surgeon believed he or she was facing inoperable adenocarcinoma, this will result in the primary tumour and especially the bulk of mesenteric metastases not being removed. Re-operation is then strongly recommended to remove the remaining mesenteric tumour, which may otherwise cause future abdominal complications.60,61,70–73

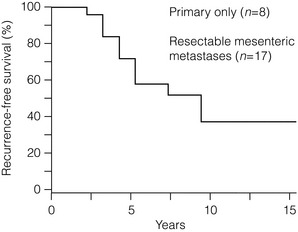

If grossly radical removal of the primary tumour and mesenteric metastases has been accomplished, small-intestinal NET patients may often remain symptom free for long periods. However, small-intestinal NETs are markedly tenacious and recurrence should be looked out for, as the majority of patients (> 80%) will ultimately develop liver metastases if follow-up is long enough (Fig. 6.5).60,61,70,73 The small-intestinal NETs are unusually slow-growing tumours, and clinically overt recurrence occurs after a median of 10 years and up to 25 years.60,73 Earlier diagnosis of such recurrence may be more sensitively based on serum chromogranin A estimates, rather than urinary 5-HIAA measurements.

Figure 6.5 Recurrence-free survival in small-intestinal NET patients subjected to apparently curative surgery. A majority of patients will experience recurrence during long-term follow-up. Reproduced from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52; and Makridis C, Öberg K, et al. Progression of metastases and symptom improvement from laparotomy in midgut carcinoid tumors. World J Surg 1996; 20:900-907, with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media.

Many patients with small-intestinal NETs lack acute abdominal symptoms, and instead present with liver metastases and sometimes also features of the carcinoid syndrome at the time of diagnosis. Only a few decades ago, life expectancy was poor in patients with liver metastases and carcinoid syndrome, with an expected median survival of around 2 years, and abdominal surgery was not often considered.10 Now, symptoms of the carcinoid syndrome may be efficiently controlled by medical treatment with somatostatin analogues and interferon, and these and other new treatment modalities have increased life expectancy and quality of life.10,60,61,70

Abdominal complications have become of increased concern and have appeared as a principal cause of death in patients with small-intestinal NETs.60,70 Such threatening complications have widened indications for abdominal surgery in patients undergoing medical treatment for the advanced NETs.

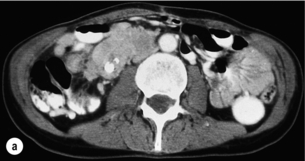

Due to continued growth and increased intestinal entrapment by mesenteric tumour or fibrosis, patients often experience abdominal pain and will require surgery for relief of partial or complete intestinal obstruction.60,61,70,71 Since incipient intestinal ischaemia may cause similar symptoms of feeding-related crampy abdominal pain, laparotomy may be urgently needed to distinguish these causes. Liberal operative intervention is also indicated because incipient venous ischaemia may contribute adversely to the patient’s condition with diarrhoea and general malaise. Occasional patients present with severe abdominal pain, weight loss, and even malnutrition and cachexia due to the intestinal ischaemia (Fig. 6.6).60,61,70–73 Abdominal pain is unlikely to occur due to the carcinoid syndrome, and weight loss and malnutrition are rarely caused merely by a large tumour burden in small-intestinal NET patients. Complications of the mesenteric tumour are evident in a large proportion of patients with small-intestinal NETs subjected to laparotomy, and are important to recognise since these patients may benefit from considerable long-term palliation following surgery.70–73

Figure 6.6 (a) Computed tomography image of mesenteric tumour deemed inoperable at previous surgery, with resulting progressive intestinal vascular impairment, weight loss and cachexia. (b) Re-operation with mesenteric tumour removal and limited intestinal resection performed with alleviation of abdominal symptoms. Part (b) reproduced from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

The natural course of mesenterico-intestinal disease with small-intestinal NETs can be variable, but surgery at an early stage is a distinct advantage, as it may provide an exceptional chance to remove the mesenteric tumour before more extensive involvement of major mesenteric vessels has occurred.61,70–73 The authors thus advocate removal of the mesenterico-intestinal tumour as a prophylactic procedure even in asymptomatic patients considered for medical therapy.73 During periods of medical treatment patients are likely to benefit markedly from close cooperation between internists and surgeons, with liberal surgical consultations when abdominal symptoms occur.

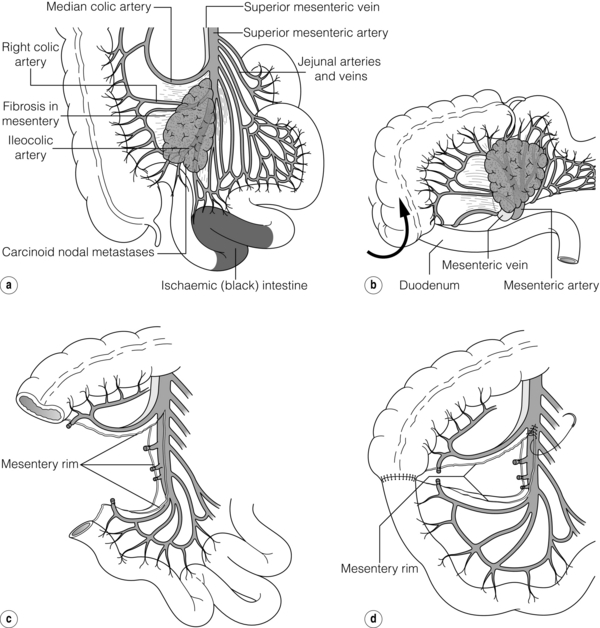

Surgical technique

Important considerations for abdominal surgery in patients with small-intestinal NETs have been outlined.60,61,71 During surgical exploration advanced small-intestinal NETs may seem inoperable since the large mesenteric metastases with surrounding fibrosis and entrapped loops of intestine will frequently appear to encase the major intestinal vascular supply.61,71 Incautious wedge resection in the fibrotic and contracted mesentery may easily compromise the main mesenteric artery and cause devascularisation of a major part of the small intestine and result in a short-bowel syndrome.60,61,71 However, since the majority of these metastases originate from primary lesions in the most terminal parts of the ileum, they tend to be deposited mainly on the right side of the mesenteric artery, implying that they can often be removed without interfering with the main intestinal vascular supply. A procedure has been described where the right colon and the entire small-intestinal mesenteric root are mobilised from adhesions to the retroperitoneum up to the level of the horizontal duodenum and the pancreas.60,61,71 A large tumour deposit in the mesenteric root and fibrosis often has to be dissected from the serosa of the horizontal duodenum. With a posterior view in the elevated mesenteric root it is possible to identify the mesenteric vessels, divide the fibrotic surroundings of the mesenteric metastases, and free-dissect and debulk a major portion, or the entire tumour, from the mesenteric root (Figs 6.6 and 6.7). Sometimes part of the tumour may be cleaved to allow separation from the mesenteric artery and vein, since the tumour seems rarely to invade the vessel walls. The procedure can preserve the main mesenteric artery and vein, and maintain blood flow through jejunal and ileal arteries and important arcades along the intestine (Fig. 6.6). The larger of the mesenteric metastases (up to 10 cm in our experience) can occasionally be easier to dissect than the smaller and diffusely fibrotic ones, which may grow more diffusely around the mesenteric root. The procedure will generally permit a more limited small-intestinal resection, and thereby a reduced risk of creating a short bowel, which is likely to be very troublesome for the patient in combination with the carcinoid syndrome. Generally, the right colon has to be removed together with the most terminal parts of the ileum, and occasionally fibrotic entrapment of the transverse or the sigmoid colon has to be released. In our experience, intestinal bypasses should be avoided as far as possible, because ischaemia may develop in a disengaged intestinal segment, and also because the mesenteric tumour will continue to grow and symptoms then generally progress. The bypass procedure can markedly complicate repeat surgery, which often becomes necessary in these patients.60,61,71 Intestinal bypassing should be reserved for cases where extensive tumour growth, carcinoidosis or fibrosis after previous operations inhibit appropriate mesenteric dissection.

Figure 6.7 Resection of small-intestinal NET primary tumour and mesenteric metastasis. (a) Mesenteric tumour may extensively involve the mesenteric root and appear impossible to remove. (b) Mobilisation of caecum, terminal ileum and mesenteric root by separation of retroperitoneal attachments allows tumour to be lifted, approached also from posterior angle, and separated from duodenum and main mesenteric vessels, with preservation of intestinal vascular supply and intestinal length. (c,d) Bowel anastomosed and mesenteric defect repaired. Redrawn from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

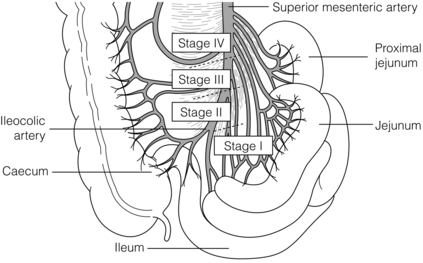

When planning dissection of mesenteric metastases it is valuable to preoperatively map the level of extension in the mesenteric root with dynamic CT investigation (Fig. 6.8).60,71 For jejunal NETs and occasional ileal NETs mesenteric metastases extend high or completely surround the mesenteric root or even extend retroperitoneally above the pancreas, and these tumours have been inoperable in our experience.

Figure 6.8 Surgical/anatomical stages of small-intestinal NET mesenteric metastases. Stage I tumours located close to the intestine, removed by limited ileal resection. Stage II tumours involving arterial branches close to the origin in the mesenteric artery, requiring right-sided colectomy, distal ileal resection and dissection from mesenteric vessels. Stage III tumours extending along but without encircling the mesenteric trunk may be free-dissected. Stage IV tumours growing around the mesenteric trunk involving origins of proximal jejunal arteries, median colic artery or extending retroperitoneally; these tumours have proved impossible to remove. Redrawn with permission from Öhrvall U, Eriksson B, Juhlin C et al. Method of dissection of mesenteric metastases in mid-gut carcinoid tumors. World J Surg 2000; 24: 1402–8; and Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media.

Repeated surgery may sometimes be required in patients with advanced small-intestinal NETs, when they suffer from chronic or intermittent abdominal pain due to partial or complete intestinal obstruction, or segmental intestinal ischaemia.60,61,71 These operations may be exceedingly difficult and time-consuming due to the presence of harsh fibrosis and carcinoidosis between loops of intestine, but nevertheless they are crucially important for the well-being of the patient. Re-operations, and indeed any surgery in patients with small-intestinal NETs, should be undertaken with great caution, since minor mistakes may easily cause intestinal fistulation, devascularisation of major parts of the small intestine, or creation of a short-bowel syndrome.60,61,71 Duodenal fistulation can be a significant risk, which has been described in this context. Emphasising these difficulties, it is recommended that the surgery for small-intestinal NETs be referred to colleagues with experience in this management.

Prophylactic removal of the mesenterico-intestinal tumour is strongly recommended even in the absence of abdominal symptoms, as this may prevent intestinal complications. Tardy surgical consultation may allow the disease to be increasingly difficult or impossible to manage surgically.71–74

Liver metastases

The treatment of liver metastases can use many modalities: medical treatment, surgery, radiofrequency (RF) ablation, liver embolisation, transplantation, radiolabelled octreotide therapy and [131I]meta- iodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG) therapy.10,46,60,61,70–74 An initial period of medical treatment with somatostatin analogues and interferon can help alleviate symptoms and slow disease progression. It also allows some time for observation and makes surgery or ablation of liver disease safer. Liver surgery is more likely to be beneficial in patients with classical small-intestinal NETs of low grade (high differentiation and low proliferation rate demonstrated by Ki67 staining).10

Liver surgery

In 5–10% of cases, solitary and unilateral or grossly dominant liver metastases occur (Fig. 6.9). Liver surgery consisting of formal hepatic lobectomy or parenchyma-saving liver resections should be undertaken, and this may be combined with wedge resections or simple enucleations of superficially located additional, and even bilateral, lesions.11,60,61,69,75–80 Recent developments of surgical and anaesthesiological methods now allow safe multiple wedge resections for bilobar hepatic metastases.80 Two-stage surgical resection may reduce the risk of liver insufficiency, with initial resection of one lobe and removal of additional tumour after some months of liver regeneration. Preoperative portal embolisation may help induce regeneration of a hepatic lobe (without metastases) that is planned to remain after hepatic lobectomy for removal of metastatic tumour.80

Figure 6.9 Computed tomography image of large small-intestinal NET metastasis within the left liver lobe. The patient had smaller metastases in contralateral liver but remained free from carcinoid syndrome 4 years after resection of the larger lesion. Reproduced from Åkerström G, Hellman P, Öhrvall U. Midgut and hindgut carcinoid tumors. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B (eds) Surgical endocrinology, 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001; pp. 448–52. With permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Debulking liver surgery may be increasingly important in patients who no longer respond to medical therapy, and larger metastases may represent cloned tumour cells that have ceased to be affected by medical therapy. Outcome is poorer in patients with more than 50% liver involvement or with more rapidly proliferating lesions.78,80 Since liver surgery may considerably relieve symptoms associated with the carcinoid syndrome, it may also be indicated in the presence of concomitant or bilateral smaller metastases.

The indications for liver surgery may be widened by combination with other treatment modalities, especially RF ablation.81–84

However, virtually every patient will recur with new tumour after liver resection or ablative therapy, if follow-up time is long enough. Reflecting slow progression of NETs, clinical symptoms (e.g. carcinoid syndrome) have reappeared 4–5 years after apparently ‘curative’ liver resection, but the patient may have been efficiently palliated until then.69,70,75–80

Radiofrequency or microwave ablation

Radiofrequency (RF) ablation has recently been introduced as an efficient and safe method for ablation of moderately large liver metastases.81–84 Using a needle introduced with ultrasound guidance into the tumour, the application of current with alternating radiowave-length frequency induces ionic oscillation, with production of heat around the needle leading to tissue necrosis within a range of around 4–5 cm. RF ablation can be performed intraoperatively, laparoscopically or repeatedly as a percutaneous ultrasound-guided procedure. Somewhat larger tumours may be coagulated by overlapping treatment or by reduction of hepatic circulation during ablation, with hepatic artery clamping during surgery, or concomitant embolisation during percutaneous RF ablation. However, tumours larger than 4 cm and tumours close to major vessels may be inefficiently treated (due to heat loss through the perfusing vessels). Although survival advantage after RF treatment remains to be verified, the treatment has been demonstrated to provide symptom relief for patients with liver metastases from small-intestinal NETs.84 Recently microwave therapy has become an alternative, but is not as sensitive for cooling by larger vessels close to the lesion.

We use RF ablation and surgery as complementary therapies, and have found that the possibility of ablation has broadened indications for surgery of bilateral tumours with the aim of cytoreduction.82–84 However, the number of lesions needs to be limited (n < 7) and the method is of less value in patients with numerous small metastases. Although methods for visualisation of liver metastases have improved, our experience from operations confirms that many patients have multiple small liver metastases, often not accurately visualised before surgery. A correct estimate of the spread is therefore often best achieved at laparotomy, where availability for surgical resection or RF ablation can be appropriately evaluated. Our own series has shown local recurrence after RF ablation in 10% and a complication rate of ∼ 5%.82,84 Since large vessels reduce the efficiency and bile ducts seem to be the most vulnerable structures, we try to avoid RF treatment of tumours located in the hepatic hilum.84

Liver embolisation

Liver tumours are generally fed mainly by arterial supply, and obstruction of the blood flow will cause tumour ischaemia. As a consequence, liver metastases may be efficiently treated by selective liver artery embolisation. Embolisation with gel foam powder, sometimes performed as a repeated procedure, has provided tumour regression and symptomatic control in approximately 50% of patients during median follow-up of 7–14 months, and with resulting reduced need for somatostatin analogues and improved effects of interferon treatment.10,11,46,85–89

Patent portal blood flow is crucial for perfusion of the normal liver parenchyma, and angiography is performed prior to embolisation to verify a patent portal vein and to characterise the vascular anatomy.46 Embolisation is generally contraindicated if tumour burden relative to normal liver parenchyma exceeds 50%, and in patients with raised bilirubin and liver enzymes as signs of hepatic insufficiency. Superselective and repeated embolisations with some months’ interval has been performed in cases with large tumours, and in patients with recurrent tumour after previous hemihepatectomy.

The procedure is associated with complications, and even mortality rates around 5%, and may cause liver insufficiency of variable degree.46 Most common is transient elevation of liver enzymes, and 2 or 3 days of fever, nausea and abdominal pain, with disappearance of symptoms within a week.

Chemoembolisation is arterial embolisation combined with intra-arterial infusion of chemotherapy and may be more effective than embolisation alone, with possibly more pronounced tumour reduction in some cases.87 The treatment may have severe side-effects and may be less efficient in small- intestinal NETs with their typically low proliferation than in tumours with lower differentiation and higher proliferation rates.

Liver transplantation

Liver transplantation may be considered for patients with liver metastases from small-intestinal NETs because of generally slow disease progression.80,90–95 Meta-analysis of patients with endocrine tumours subjected to liver transplantation revealed a nearly 50% 1-year survival but varying 5-year survival (24–48%), possibly due to different selection procedures between centres.90 Gastrointestinal NETs have been reported with more favourable survival (69% at 5 years) than endocrine pancreatic tumours.91 Recent results indicate reduced operative risks and improved results after transplantation in neuroendocrine tumours, with up to 77% 1-year tumour-free survival, 90% overall 5-year survival, but only around 20% 5-year tumour-free survival.92–95 Ki67 proliferation index < 5–10% and absence of markers for aggressive tumours have generally been required.95 Patients should have extra-abdominal metastases excluded by biochemical markers and sensitive imaging with specific tracers, but spread disease is not invariably detected. The new liver will often become the site for new metastases, emphasising that GEP-NETs are tenacious, with high recurrence rate also after apparently radical removal of regionally localised lesions.73 Indications for transplantation must be balanced against favourable results of medical treatment and the possibility that immunosuppression can promote tumour growth. Cases considered for liver transplantation therefore have to be carefully selected, and perhaps chosen from patients in whom liver metastases cannot be removed, are markedly space occupying or threaten to cause liver failure, though limited tumour burden (< 50% of liver volume) has also been favourable for transplantation.

Prophylaxis against carcinoid crisis

As prophylaxis to prevent crisis during surgery or intervention, patients with small-intestinal NETs should preferably be pretreated with octreotide (patient’s regular dose or daily 100 μg × 3, s.c.). Adrenergic drugs should generally be avoided if hypotension should occur during surgery.11,60,96 Patients with foregut NETs and atypical carcinoid syndrome are treated with octreotide, histamine blockade and cortisone, and avoidance of histamine-releasing agents (morphine and tubocurarine). In patients with carcinoid flush syndrome we routinely provide i.v. octreotide (500 μg in 500 mL saline, 50 μg/h) during surgery or embolisation procedures, and the same treatment or increased dose (100 μg/h) is given if carcinoid crisis should occur.60,96

Medical treatment

Somatostatin analogues (octreotide, lanreotide) have been a breakthrough in the treatment of NETs.10,11,46 By binding to specific somatostatin receptors (types 2 and 5) the analogues reduce the release of bioactive peptides from tumour cells and may also block peripheral responses of target cells. They may also inhibit tumour growth, induce apoptosis, counteract angiogenesis and have, in randomised evaluation, recently been demonstrated to reduce tumour growth in metastatic small-intestinal NETs.100

Interferon-α (IFN-α) reduces hormone secretion and stimulates natural killer cells with effects on cell growth in tumours with slow progression.10,46,97–99 Clinically, IFN-α administration induces biochemical and subjective responses in about 50% of the patients, with antitumour effects in around 10% and stabilisation of the disease in 35%.98,99 Recently, a pegylated form has become available (PegIntron®) for subcutaneous administration once a week, and with possible improved tolerance. Combinations of somatostatin analogue and interferon therapy may increase response rate. Interferon is associated with more adverse effects than somatostatin analogues, mainly flu-like symptoms initially, and later on chronic fatigue and sometimes depression. Autoimmune phenomena may be induced, causing thyroid dysfunction by antithyroid antibodies and occasionally other complications. Neutralising interferon antibodies may develop and interfere with the effects.46 Some patients have to discontinue treatment, and the rather high risk of side-effects has limited the use of interferon.

Radiotherapy

External radiotherapy is generally not efficient in treating NETs but it can be used for long-term palliation of brain metastases, and especially for alleviation of pain due to bone metastases.10

Internal or tumour-targeted radiation has been developed during recent years, using 131I-MIBG and radioactive somatostatin analogues.101,102 Effects of 131I-MIBG therapy have been limited, with subjective responses in 30–40% of patients and biochemical responses in less than 10%.101 Predosing with non-labelled MIBG has resulted in prolonged biochemical and clinical responses.

NETs usually express somatostatin receptor subtypes 2 and 5, which become internalised in tumour cells after binding of radiolabelled octreotide.46,102 New compounds with beta- and gamma-emitting isotopes linked to somatostatin analogues have been developed ([90Y-DOTA]octreotide and [177Lu-DOTA, Tyr3]octreotate), with affinity for different somatostatin receptors and better tumour penetration.102,103 Some of these compounds have shown promising responses and moderate side-effects.46,102,103

Survival

Age-adjusted overall 5-year survival for all small-intestinal NETs in Sweden between 1960 and 2000 was 67%, which was similar to the series from the SEER Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), 1973–1999.1,104

Patients with inoperable liver metastases in the Uppsala series had 50% 5-year survival and survival was 42% with inoperable liver and mesenteric lymph node metastases.72 Survival was better for younger age groups (< 50 years), and worse for patients with para-aortal lymph node spread and peritoneal carcinomatosis.72,74 Other negative factors for survival (except for liver metastases and heart disease) have been high 5-HIAA values, old age (> 75 years), tumour discovered during emergency surgery, significant weight loss and presence of extra-abdominal metastases.70,72,74,104–106

Appendiceal NETs

Appendiceal NETs constitute ∼ 5–8% of GEP-NET, having apparently decreased in frequency.1,11,107–109 NET is one of the most common tumours of the appendix. The majority of appendiceal NETs originate from serotonin-producing EC cells.11 The tumours appear to have a neuroectodermal origin and more benign features than other NETs.107 Appendiceal NETs are prevalent at autopsy and rarely attain clinical significance. Many may perhaps undergo spontaneous involution, since the prevalence is reported as higher in children than in adults.107

Appendiceal NETs are often an incidental finding at surgery, and are expected to occur in 1 in 200 appendectomies,107 but have probably frequently been overlooked. Approximately 75% of the NETs are located in the tip of the appendix (Fig. 6.10), and therefore only a few cases have had appendicitis due to an occluded appendix lumen.107 Patients with appendiceal NETs are generally younger than those with other NETs, having a mean age ∼ 40 years, with a slight female predominance, and even children may be affected. The overall metastasis rate has been determined as 3.8%, with distant metastases in 0.7%.1 Patients with larger tumours and metastases tend to be younger (29 years) than patients with smaller benign lesions (42 years).11

Figure 6.10 Appendiceal NET, with the typical yellow colour and location in tip of the appendix. Reproduced with permission from Capella C, Solcia E, Sobin L et al. Endocrine tumours of the appendix. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA (eds). WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press, 2000; pp. 99–101.

The prognosis for appendiceal NETs is favourable overall, with a 5-year survival rate of 84% for patients with regional metastases and 28% for the few patients with distant metastases.11,107–109

Atypical goblet-cell NETs

Adenocarcinoid or goblet-cell NET represents a more malignant variant, with elements of NETs and mucinous adenocarcinomas, the most common origin being in the appendix.107–110 This type has also been named ‘atypical’ or ‘intermediate’ carcinoid. The tumour is more malignant than the classical NET, and resembles classical adenocarcinoma with respect to prognosis and survival. The tumours do not express somatostatin receptors and cannot be visualised by OctreoScan®. Special histological markers may be used to identify the lesions. Although many goblet-cell NETs may be localised, some have aggressive spread in the mesoappendix and intraperitoneally. Treatment for this tumour has mainly included extended ileocolic and mesenteric resection, often performed as re-operation, and additionally chemotherapy.107–110 The goblet-cell NETs have had unpredictable and generally less favourable survival, with a 60% 10-year survival rate.107–110 Recently a more aggressive therapy has been proposed, adding cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal heated chemotherapy.111 The cytoreductive therapy has included omentectomy, splenectomy and peritonectomy.

Colon NETs

NETs of the colon are rare and constitute only ∼ 8% of GEP-NETs and 1–5% of colorectal neoplasms.1,11,112–114 These tumours develop preferentially in older individuals, with a mean age of 65 years, but have also occasionally been reported in children. Tumours of the proximal colon (caecum) are most common and may infrequently (5%) be associated with the carcinoid syndrome, which does not occur in association with more distally located colonic lesions.113 The majority of colon NETs have less well-differentiated histological features, are generally large and exophytic, rather than ulcerating, apparently slow growing, and may reach conspicuous size before diagnosis. These tumours have a higher proliferation rate, commonly regional metastases, and high incidence of liver metastases.113 Patients generally present with typical malignant symptoms, pain, palpable abdominal mass and, more occasionally, occult rectal bleeding. Tumours of the right colon may be larger, when detected, than those of the left colon, which may cause obstruction. Occasional tumours have been encountered in patients with colitis or Crohn’s disease.113 Although some authors have recommended limited resection for colon NETs < 2 cm in diameter, it is probably wise to treat all patients with hemicolectomy, using similar principles as for colon adenocarcinoma. Due to their slow growth rate, palliative tumour debulking may also be undertaken if possible. The 5-year survival rate for colon NETs has averaged 37%, slightly better than the survival for adenocarcinoma.113

Rectal NETs

Rectal NETs have previously been regarded as uncommon, but the incidence is increasing, and they constitute ∼ 15–20% of GEP-NETs and 1–2% of all rectal tumours.1,112–115 Genetic predisposition may be noted in the different annual incidence of approximately 0.35 per 100 000 in whites and 1.2 in black people, as well as a roughly fivefold higher incidence in the Asian compared with the non-Asian North American population. The increased incidence compared with earlier reports may be due to increased awareness of the diagnosis and use of recently developed diagnostic methods, such as endosonography, as well as more accurate histopathology. The majority of rectal NETs are small and discovered accidentally at early stages. The overall prognosis is favourable, with up to 88.3% 5-year survival,1 although a more thorough classification of different variants of rectal NETs is probably mandatory.

Presentation

The development of the tumour usually occurs in the sixth decade, about 10 years earlier than non-NET rectal tumours. The majority – up to about 60% – are small, less than 1.0 cm in greatest dimension (Fig. 6.11),112,113 and may be discovered after presenting symptoms such as perianal pain, pruritus ani or haematochezia leading to endoscopic procedures. However, most patients are asymptomatic and the tumours are found incidentally, which is prognostically beneficial compared with symptomatic presentation. The smaller tumours usually present as submucosal yellowish nodules, and up to 75% may be within reach of digital examination at 8 cm from the anal verge. The findings at digital palpation can be variable and described as firm, smooth or rubbery in consistency. Diagnosis is made after histopathological evaluation of biopsies or after removal of the whole nodule. Patients with tumours < 1 cm exhibit a low risk for metastases (< 2%).112–115

Figure 6.11 Rectal neuroendocrine polyp with typical yellowish colour and submucosal location. Reproduced with permission from McNevin MS, Read TE. Diagnosis and treatment of carcinoid tumors of the rectum. Chir Int 1998; 5:10–12.

Tumours exceeding 1.0 cm in greatest dimension are much more prone to dissemination. Thus, patients with tumours between 1.0 and 1.9 cm have an intermediate incidence of metastatic spread (10–15%), while patients with larger tumours (> 2 cm) exhibit a 60–80% incidence of distant metastases. The main sites for tumour spread are regional lymph nodes and the liver, and less commonly lung and bone.113

Rectal NETs may prognostically and in terms of management be divided according to their size. Patients with tumours < 1 cm seldom demonstrate symptoms, have a favourable outcome, are generally cured by local excision and almost never have metastases. Patients with tumours > 2 cm usually present with symptoms and the majority have metastases to regional lymph nodes, lung or liver. Thus, the smaller (< 1 cm) and the larger (> 2 cm) tumours have a predictable outcome, whereas tumours measuring 1.0–1.9 cm in diameter are unpredictable.112,113 Although patients with smaller tumours generally may be considered as cured after tumour excision, patients with tumours measuring 1.0–1.9 cm need to be thoroughly examined for the presence of local infiltration and metastatic disease, and should also be closely surveyed. Transrectal endosonography should be used for more precise assessment of tumour extension, possible infiltration in the muscularis propria, and to reveal regional lymph node metastases. CT or MRT can clarify local tumour growth in the pelvis, and also the presence of lymph node and liver metastases. Octreotide scintigraphy (OctreoScan®) is often negative in patients with rectal NETs due to lack of or few somatostatin receptors, but should nevertheless be used since some tumours express these receptors and this may provide effective treatment options.

Diagnosis and immunohistochemistry