Chapter 35 Gastrointestinal Emergencies

7 Distinguish among hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena

Hematemesis is the vomiting of bright red or denatured blood (“coffee-ground” appearance). The source of the blood is proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

Hematemesis is the vomiting of bright red or denatured blood (“coffee-ground” appearance). The source of the blood is proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

Hematochezia is bright red blood or maroon-colored stools per rectum and implies a lower GI source (colon).

Hematochezia is bright red blood or maroon-colored stools per rectum and implies a lower GI source (colon).

Melena is the rectal passage of black tarry stools (black from the bacterial breakdown of blood); the source is proximal to the ileocecal valve.

Melena is the rectal passage of black tarry stools (black from the bacterial breakdown of blood); the source is proximal to the ileocecal valve.

8 Distinguish between upper GI and lower GI bleeding in terms of site of bleeding

9 What are some of the common tests used to determine the presence of blood? What causes them to be falsely positive or falsely negative?

14 What are some common causes of upper GI bleeding in infants and children?

Neonates: Swallowed maternal blood, esophagitis, coagulopathy, sepsis, gastritis (stress ulcer)

Neonates: Swallowed maternal blood, esophagitis, coagulopathy, sepsis, gastritis (stress ulcer)

Infants (age 1–12 months): Gastritis, esophagitis, Mallory-Weiss tear, duplication

Infants (age 1–12 months): Gastritis, esophagitis, Mallory-Weiss tear, duplication

Children (age 1–12 years): Epistaxis, esophagitis, gastritis, ulcers, Mallory-Weiss tear, esophageal varices, toxic ingestion

Children (age 1–12 years): Epistaxis, esophagitis, gastritis, ulcers, Mallory-Weiss tear, esophageal varices, toxic ingestion

Adolescents: Ulcers, esophagitis, varices, gastritis, Mallory-Weiss tear, toxic ingestion

Adolescents: Ulcers, esophagitis, varices, gastritis, Mallory-Weiss tear, toxic ingestion

15 What are some common causes of lower GI bleeding in infants and children?

Neonates: Swallowed maternal blood, anorectal lesions, milk allergy, necrotizing enterocolitis, midgut volvulus, Hirschsprung’s disease

Neonates: Swallowed maternal blood, anorectal lesions, milk allergy, necrotizing enterocolitis, midgut volvulus, Hirschsprung’s disease

Infants (age 1–12 months): Anal fissure, midgut volvulus, intussusception, Meckel’s diverticulum, infectious diarrhea, milk allergy

Infants (age 1–12 months): Anal fissure, midgut volvulus, intussusception, Meckel’s diverticulum, infectious diarrhea, milk allergy

Children (age 1–12 years): Anal fissures, polyps, Meckel’s diverticulum, intussusception, infectious diarrhea, inflammatory bowel disease, duplications, hemangiomas, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome

Children (age 1–12 years): Anal fissures, polyps, Meckel’s diverticulum, intussusception, infectious diarrhea, inflammatory bowel disease, duplications, hemangiomas, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome

Adolescents: Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease), polyps, hemorrhoids, anal fissure, infectious diarrhea

Adolescents: Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease), polyps, hemorrhoids, anal fissure, infectious diarrhea

18 What is the radiographic finding in an infant with malrotation and volvulus?

KEY POINTS: ETIOLOGY OF VOMITING

1 The most common cause of vomiting in older children is acute gastroenteritis.

2 Vomiting can occur from extra-GI problems, such as infections (meningitis, urinary tract infections), metabolic (inborn errors of metabolism, diabetic ketoacidosis), drugs/toxins (iron, lead), and pregnancy.

3 An infant under 1 month of age (outside of the nursery) with bilious vomiting and abdominal pain and distention has malrotation (with or without volvulus) until proven otherwise.

19 Is a “currant jelly” stool classic for intussusception?

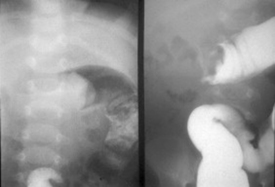

Up to 75% of children with intussusception never have visible blood in the stool (although the stool is guaiac-positive). A currant jelly stool is a late finding because it implies that bowel necrosis has occurred. Intussusception generally occurs in children under 2 years of age, with a peak age range of 5–9 months. Classic symptoms occur in 10% of cases and include the sudden onset of severe, intermittent, crampy abdominal pain, with crying and drawing up of legs in episodes every 15 minutes. This is followed by vomiting and the passage of a “currant jelly” stool. There is also a “neurologic presentation,” which consists of lethargy followed by brief periods of irritability. Abdominal radiographs (Fig. 35-1) may show a soft tissue mass, a nascence of cecal gas and stool, a target sign, a meniscus or crescent sign, a paucity of bowel gas, or a bowel obstruction. Definitive diagnosis and treatment in >75% of cases are made by barium or air contrast enema (hydrostatic reduction). The most common location for the intussusception is ileocolic. Lead point is usually not present in younger children but is somewhat common in older children (e.g., Meckel’s diverticulum, duplication, vasculitis due to Henoch-Schönlein purpura).

21 A child who has had surgical correction for Hirschsprung’s disease presents with fever, abdominal distention, and diarrhea. What is your concern?

Dasgupta R, Langer JC: Hirschsprung disease. Curr Prob Surgery 41: 949–988, 2004.

24 What are some therapies for H. pylori infection in children?

Amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg/d (up to 1 gm twice daily)

Amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg/d (up to 1 gm twice daily)

Clarithromycin, 15 mg/kg/d (up to 500 mg twice daily)

Clarithromycin, 15 mg/kg/d (up to 500 mg twice daily)

Proton-pump inhibitor (e.g., omeprazole), 1 mg/kg/d (up to 20 mg twice daily)

Proton-pump inhibitor (e.g., omeprazole), 1 mg/kg/d (up to 20 mg twice daily)

KEY POINTS: GASTRITIS/PEPTIC ULCERS AND HELICOBACTER PYLORI

1 H. pylori is associated with gastric and duodenal ulcers in children.

2 Endoscopy with biopsy is the preferred method for diagnosis. The serologic tests are not reliable in children. The urea breath tests are reliable in older children, but have not been studied adequately in children under 2 years.

3 H. pylori is an infrequent cause of recurrent abdominal pain in children.

4 Treatment is indicated in symptomatic patients with proven H. pylori infection.

25 Describe some of the anatomic and histologic differences between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

Ulcerative colitis: Inflammation of the mucosa and submucosa limited to the colon and rectum, continuous involvement in these regions. There are various degrees of ulceration, hemorrhage, edema, and pseudopolyps.

Ulcerative colitis: Inflammation of the mucosa and submucosa limited to the colon and rectum, continuous involvement in these regions. There are various degrees of ulceration, hemorrhage, edema, and pseudopolyps.

Crohn’s disease: Can involve any portion of the alimentary tract, including the upper GI tract (30–40% of cases), small bowel (90%), and distal ileum (70%). There is transmural inflammation, with discrete lesions (“skip lesions”). Because of the full-thickness involvement, there can be focal ulcerations, fistulae, strictures, adhesions, and a cobblestone appearance.

Crohn’s disease: Can involve any portion of the alimentary tract, including the upper GI tract (30–40% of cases), small bowel (90%), and distal ileum (70%). There is transmural inflammation, with discrete lesions (“skip lesions”). Because of the full-thickness involvement, there can be focal ulcerations, fistulae, strictures, adhesions, and a cobblestone appearance.

26 What are some of the extraintestinal features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease?

29 What is celiac disease?

Shamir R: Advances in celiac disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 32:931–947, 2003.

34 What causes pancreatitis in children?

Acute pancreatitis in children is due to one of several causes:

Anatomic/structural abnormalities (choledochal cysts, biliary stone, tumors)

Anatomic/structural abnormalities (choledochal cysts, biliary stone, tumors)

Drugs and toxins (acetaminophen overdose, antibiotics, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, anti-inflammatories, neoplastic agents)

Drugs and toxins (acetaminophen overdose, antibiotics, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, anti-inflammatories, neoplastic agents)

Infections (E. coli, Ascaris lumbricoides, varicella, mumps, influenza B, HIV)

Infections (E. coli, Ascaris lumbricoides, varicella, mumps, influenza B, HIV)

Trauma (disruption of pancreatic ducts, compression injury)

Trauma (disruption of pancreatic ducts, compression injury)

Familial/hereditary (cystic fibrosis)

Familial/hereditary (cystic fibrosis)

Metabolic (hyperlipidemia, hyperparathyroidism, malnutrition)

Metabolic (hyperlipidemia, hyperparathyroidism, malnutrition)

36 What are the criteria necessary to make the diagnosis of cyclic vomiting syndrome?

Three or more episodes of vomiting within the last year

Three or more episodes of vomiting within the last year

No symptoms between episodes of vomiting

No symptoms between episodes of vomiting

Acute onset of vomiting with each episode, with each one lasting no more than 1 week

Acute onset of vomiting with each episode, with each one lasting no more than 1 week

Li BU: New hope for children with cyclic vomiting syndrome. Contemp Pediatr 19:121, 2002.