CHAPTER 9 Gastrointestinal disorders

Gastrointestinal assessment: general

Goal of system assessment

Evaluate for dysfunctional ingestion and digestion of food and elimination of waste products.

Auscultation

Evaluate bowel sounds in each of the quadrants in a systemic fashion.

• Hyperactive bowel sounds—may indicate diarrhea or early intestinal obstruction

• Hypoactive to absent bowel sounds—may indicate paralytic ileus or peritonitis

• High-pitched rushing sounds—may indicate intestinal obstruction

Evaluate for systolic bruits (humming, swishing, or blowing sounds) over:

Nutritional assessment

![]() Evaluate for risk factors and indications of malnutrition for which critically ill patients are at risk. Malnutrition may occur due to negative caloric intake with concomitant GI obstruction, malabsorption syndromes, infectious diseases, certain medications, and surgical treatment. Additionally, caloric needs are greatly increased in the critically ill as a result of hypermetabolic states produced by trauma, fever, sepsis, and wound healing.

Evaluate for risk factors and indications of malnutrition for which critically ill patients are at risk. Malnutrition may occur due to negative caloric intake with concomitant GI obstruction, malabsorption syndromes, infectious diseases, certain medications, and surgical treatment. Additionally, caloric needs are greatly increased in the critically ill as a result of hypermetabolic states produced by trauma, fever, sepsis, and wound healing.

| Body System | Signs | Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Skin, nails | Dry skin Brittle nails; spooned-shaped nails |

Vitamin deficiency Iron deficiency |

| Mouth | Cracks; beefy, red tongue | Vitamin deficiency |

| Stomach | Decreased gastric acidity Delayed gastric emptying |

Protein deficiency |

| Intestines | Decreased motility and absorption Diarrhea |

Protein deficiency Altered normal flora |

| Liver/biliary | Hepatomegaly Ascites |

Decreased absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, Protein deficiency |

| Cardiovascular | Edema Tachycardia; hypotension |

Protein deficiency Fluid volume deficiency |

| Musculoskeletal | Decreased muscle mass Subcutaneous tissue loss |

Protein, carbohydrate, and fat deficiency |

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding

Pathophysiology

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

The most common cause of hematemesis and melena is gastroduodenal ulcer disease, accounting for half of massive UGI bleeding (UGIB) disorders. Peptic ulcers are chronic, usually solitary, lesions that are most prevalent in the stomach and duodenum. These lesions breach the protective mucosa of the GI tract extending deep into the submucosa, exposing tissue to gastric acids with eventual autodigestion. Bleeding occurs when the ulcer erodes into a blood vessel. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of peptic ulceration, much more so than gastric hyperacidity. The toxins and enzymes released by the H. pylori organism are believed to cause ulceration through proinflammatory processes and by decreasing duodenal mucosal bicarbonate production. Infection with H. pylori is present in almost all patients with duodenal ulcers and 70% of patients with gastric ulcers. In contrast, hyperacidity is present in a minority of patients with gastric ulcers and even less in those with duodenal ulcers. Bleeding occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with peptic ulceration, and perforation occurs in about 5%. Another cause of peptic ulceration is Zöllinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES). In ZES, ulcerations occur in the stomach, duodenum, and jejunum due to excess gastrin secretion by a tumor, resulting in hyperacidity with mucosal erosion. Stress ulceration is a common and potentially life-threatening phenomenon that occurs in critically ill patients, especially those who are mechanically ventilated. Stress ulcers, also known as erosive gastritis, tend to be multiple lesions, located mainly in the stomach and occasionally in the duodenum, primarily resulting from stress-related hyperacidity and mucosal ischemia. Stress ulcers occurring in the proximal duodenum are called Curling ulcers. They are associated with deep mucosal invasion and are seen in patients with major burn injury or major trauma. Cushing ulcer is a related condition occurring in patients who have sustained serious head injury, major surgery, or critical central nervous system (CNS) disorder that raises intracranial pressure. Gastritis, another common cause of peptic ulceration, usually occurs as slow, diffuse oozing that is difficult to control. Benign or malignant gastric tumors may initiate severe bleeding episodes, especially tumors located in the vascular system that supplies the GI tract.

Neighboring organs

Acute pancreatitis (see p. 762) and pancreatic pseudocyst are disorders associated with hemorrhage. Persons with intra-abdominal vascular grafts are at risk for the development of aortoenteric fistulas with massive GI hemorrhage.

Medications

Longstanding use of aspirin, corticosteroids, or anticoagulants is associated with serious GI bleeding. Ethanol may cause or potentiate ulcer bleeding as it induces gastric mucosal injury. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) cause increased risk of serious GI bleeding, ulceration, and perforation of the stomach and intestines. Traditional NSAIDs are nonselective inhibitors of both cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzymes. COX-1 enzymes regulate gastroduodenal mucosal protective mechanisms. COX-2 enzymes are involved in inflammatory and pain responses. The newer COX-2 selective inhibitors were believed to block pain and inflammation while leaving protective mucosal mechanisms intact, thereby significantly lowering the incidence of GI ulceration and bleeding compared with ![]() traditional NSAIDs. However, the COX-2 inhibitors were shown to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, especially in older adults, resulting in the removal of two of three COX-2 agents from the market. Currently, celecoxib is the only COX-2 selective inhibitor available in the United States. This COX-2 inhibitor is still associated with an increased risk for GI bleeding, while to a lesser degree than traditional NSAIDS; additionally, it does not appear to pose any greater risk for cardiovascular disease than traditional NSAIDs.

traditional NSAIDs. However, the COX-2 inhibitors were shown to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, especially in older adults, resulting in the removal of two of three COX-2 agents from the market. Currently, celecoxib is the only COX-2 selective inhibitor available in the United States. This COX-2 inhibitor is still associated with an increased risk for GI bleeding, while to a lesser degree than traditional NSAIDS; additionally, it does not appear to pose any greater risk for cardiovascular disease than traditional NSAIDs.

Gastrointestinal assessment: acute gastrointestinal bleeding

Goal of assessment

Evaluate patients for severity of active bleeding, shock states, or risk of rebleeding.

History and risk factors

History and risk factors include critical illness, especially that caused by major injury, surgery, CNS disorder, or burns; prolonged shock or hypoperfusion; organ failure; esophageal varices, excessive alcohol, NSAIDs, or corticosteroid ingestion; inflammatory bowel disease; foreign body ingestion; hiatal hernia; hepatic, pancreatic, or biliary tract disease; blood dyscrasias; penetrating or blunt trauma; familial cancer; recent abdominal surgery; and the presence of H. pylori, found in greater than 90% of patients with duodenal ulcers and 70% of those with gastric ulcers. Identification of those at risk for recurrent bleeding is essential to guide therapy and prevent poor outcomes. Risk factors associated with rebleeding are listed in Box 9-1.

Vital sign assessment

• Systolic BP less than 90 to 100 mm Hg with an HR greater than 100 beats/min (bpm) in a previously normotensive individual signals a 20% or greater reduction in blood volume.

• Orthostatic hypotension signs will be positive revealing a decrease in systolic BP greater than 10 mm Hg with an increase in HR of 10 bpm. Orthostatic hypotension is indicative of recent blood loss of at least 1000 ml in the adult.

• Respiratory rate will be mildly elevated as a response to the diminished oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. If abdominal pain is present, ventilatory excursion may be limited.

Blood loss

• The amount of blood lost and rate of bleeding will have varying effects on cardiovascular and other body systems.

• Blood loss of 1000 ml within 15 minutes usually produces tachycardia, hypotension, nausea, weakness, and diaphoresis. Adults can lose up to 500 ml of blood in 15 minutes and remain free of associated symptoms.

• Massive hemorrhage, which is generally defined as loss of greater than 25% of total blood volume or a bleeding episode that requires transfusion of 6 units of blood in a 24-hour period, can occur.

• Syncope associated with hypotension also may occur.

• Sequestration of fluid into the peritoneum and interstitium further depletes intravascular volume.

• Severe hypovolemic shock and decreased cardiac output can lead to ischemia of various organs, especially the brain and kidneys.

Abdominal pain

• Mild to severe epigastric pain is often associated with gastroduodenal ulcerative or erosive disease. The pain is described as dull or gnawing.

• As blood covers and protects the eroded tissue, pain may disappear.

• Blood can irritate the bowels, thereby increasing transit time in the lower GI tract, causing diarrhea.

Observation

• Extremities are cool and diaphoretic.

• Pallor or cyanosis may be present.

• Alterations in LOC with restlessness and confusion.

• Emesis or gastric aspirate contains obvious whole blood or old blood that resembles coffee grounds.

• Hematemesis usually occurs with UGIB from above the ligament of Treitz. Bleeding originating below the level of the duodenum is not usually associated with hematemesis.

• Jaundice, vascular spiders, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly suggest liver disease.

Hemodynamic measurements

• Hypovolemic shock usually reveals a decreased central venous pressure (CVP), pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), central venous oxygen saturation (ScVO2) and cardiac output (CO) and an increased stroke volume variation (SVV) and systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

• After major abdominal surgery, a hyperdynamic state may exist similar to that seen in early septic shock, with an increased CO and decreased SVR (see SIRS, Sepsis and MODS, p. 924).

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Studies | ||

| Complete blood count (CBC) with differential Hemoglobin (Hgb) Hematocrit (Hct) RBC count (RBC) WBC count (WBC) Platelet count |

Serial Hgb and Hct values monitor the amount of blood lost. Total counts monitor hematologic function, except for platelets, which may be nonfunctional despite normal number present. |

Hgb <10 g/dl correlates with increased rebleeding and mortality rates. The first Hct value may be near normal ∼45% because the ratio of blood cells to plasma remains unchanged initially. However, the Hct is expected to fall dramatically ∼27% as volume is restored and extravascular fluid mobilizes into the vascular space (hemodilution). Hct < 24% generally requires transfusion. Platelet count rises within 1 hour of acute hemorrhage. Leukocytosis occurs frequently following acute hemorrhage. |

| Serum chemistry BUN Creatinine BUN:creatinine (Cr) ratio Serum chloride Serum potassium Serum glucose Liver function tests (LFTs): Total bilirubin Ammonia |

To assess fluid and electrolyte status. LFTs monitor for hepatic involvement. | BUN will be elevated due to dehydration. Creatinine may be mildly elevated due to ↓ GFR secondary to hypovolemia. BUN:Cr ratio will be elevated >33:1 mg/dl in the patient with upper GI bleed. Hypochloremia, hypokalemia and ↑serum bicarbonate will be noted with excessive vomiting or gastric suction. Mild hyperglycemia is the result of the body’s compensatory response to a stressful stimulus. Hyperbilirubinemia is caused by the breakdown of reabsorbed RBCs and blood pigments. Ammonia levels are usually elevated in patients with hepatic disease. Plasma protein levels may rise in response to increased hepatic production. |

| Arterial blood gas (ABG) | Assesses acid-base status. Lactic acid levels may be drawn separately, and may be available on certain ABG analyzers. | If the shock state is severe, lactic acidosis occurs, reflected by low arterial pH and serum bicarbonate levels and the presence of an anion gap. With a low perfusion state, hypoxemia may be present. |

| Coagulation studies | Assess for preexisting hypocoagulable disease; liver disease; anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy for cardiac disease. Large blood volume transfusions may lead to the development of coagulopathies. |

Elevation of fibrinogen levels, fibrin split products (FSP), PT, PTT, INR may be seen. |

| 12-Lead ECG | Monitor for severe cardiac ischemia findings as a result of hypoperfusion. | Ischemic changes include T-wave depression or inversion. |

| Radiologic Procedures | ||

| Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) | To accurately assess the source of upper GI ulcer bleeding. To locate the ulcer, visualize and implement endoscopic therapy, such as sclerosing bleeding vessels. | Endoscopic ulcer findings (endoscopic stigmata) include: Clean ulcer base Adherent clot Visible vessel Active bleeding |

| Plain films Abdominal radiograph Chest radiograph |

To identify the presence of dilated bowel or free air. A chest x-ray is taken to establish baseline pulmonary status. |

Free air seen under the diaphragm, suggests perforation. |

| Barium studies | Usually are reserved for nonemergent situations to verify the presence of tumors or other large GI lesions. | Not usually used for acute GI bleeding as this procedure does not allow for the provision of endoscopic therapy. |

| Colonoscopy | Direct visualization of the rectum and sigmoid colon through an endoscope for diagnosis and triage of lower GI bleeding. | Mucosal bleeding, polyps, hemorrhoids, and other lesions may be identified. Biopsy specimen may be obtained. Emergent colonoscopy is difficult due to length of time for adequate bowel preparation. |

| Angiography | The visualization of active bleeding from an arterial site or from a large vein in the lower GI tract. Bleeding flow rate must be at least 0.5–1.0 ml/min to be visualized by this test. |

Clearly identifies bleeding GI arterial systems. Therapeutic arterial embolization or vasopressin infusion may be performed to stop the bleeding during angiography. Complications include dye-induced renal failure, arterial dissection and occlusion, bowel infarction, and MI with vasopressin infusion. |

| Nuclear medicine Technetium-labeled red blood cell scan |

To detect low-flow rate bleeding in the lower GI tract. Usefulness is controversial. | Identifies low-flow bleeding rates of 0.1–0.5 ml/min in the lower GI tract. Accuracy remains questionable. |

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the most accurate means of determining the source of UGI ulcer bleeding. Visualization of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum using a fiberoptic endoscope passed through the mouth is usually performed within the first 12 hours after the patient’s admission to identify the exact source of bleeding and characteristics of ulcers, if present. Endoscopic ulcer findings are referred to as endoscopic stigmata. Stigmata indicative of bleeding ulcers, bleeding esophageal varices, or ulcers at risk for rebleeding are identified in Box 9-2, Stigmata of Active or Recent Hemorrhage (SARH). SARH findings are helpful in determining the course of direct therapy as well as providing prognostic information. Antacids and sucralfate should be withheld until after the procedure, because they can alter the appearance of lesions. Gastric biopsy is usually obtained with endoscopy for H. pylori diagnosis as well as to exclude gastric malignancy.

Box 9-2 STIGMATA OF ACTIVE OR RECENT HEMORRHAGE (SARH)

Endoscopic ulcer findings from active or recent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage:

Electrocoagulation, injection therapy (epinephrine), laser, hemoclips, and other therapeutic techniques such as scleral therapy and variceal ligation (banding) may be used during this procedure to stop current bleeding or prevent further bleeding from esophageal varices or ulcers.

Collaborative management

Acute GI bleeding can occur from various lesions or sites in the GI tract. The amount of blood loss can vary from minor to massive (Table 9-2) depending on the cause, resulting in hypovolemic shock with significant associated mortality. The patients requiring intensive care ![]() management are those with moderate to massive bleeding, advanced age and significant comorbidities such as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), hepatic disease, or cardiovascular disease. Therefore, collaborative management focuses on cessation of active bleeding, identification and treatment of the underlying pathophysiology, and the prevention of rebleeding. Some patients develop GI bleeding during hospitalization for another reason as in the case of stress ulceration. Stress ulcer prophylaxis has been included in the management of mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients but is currently controversial.

management are those with moderate to massive bleeding, advanced age and significant comorbidities such as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), hepatic disease, or cardiovascular disease. Therefore, collaborative management focuses on cessation of active bleeding, identification and treatment of the underlying pathophysiology, and the prevention of rebleeding. Some patients develop GI bleeding during hospitalization for another reason as in the case of stress ulceration. Stress ulcer prophylaxis has been included in the management of mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients but is currently controversial.

| Severity of Bleed | Percent of Intravascular Blood Loss | Blood Pressure (BP) and Heart Rate (HR) Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Massive | 20%–25% | Systolic BP < 90 mm Hg HR >100 beats/min |

| Moderate | 10%–20% | Orthostatic hypotension HR >100 beats/min |

| Minor | <10% | Normal BP HR <100 beats/min |

Adapted from Rockey DC: Gastrointestinal bleeding. In Sleisenger MH, Feldman M, Fordtran JS, et al., editors: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, ed 8. Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.

Care priorities

1. Fluid and electrolyte management:

Volume replacement in acute GI bleeding must be performed as quickly as possible. Large-bore IV lines should be placed and rapid fluid resuscitation initiated. Volume replacement should include a combination of crystalloid and blood products. Unstable patients who show signs of poor tissue perfusion are generally transfused. Packed cells and fresh-frozen plasma should be balanced to provide for both the replacement of cells and clotting components. Large transfusions will cause Ca−+ to bind with the citrate (the preservative in stored blood) and deplete free Ca−+ levels. In addition, large-volume blood transfusions can lead to coagulopathy disorders. Vasopressors and inotropic agents should be used only if tissue perfusion remains compromised despite adequate intravascular volume replacement. Hemodynamic monitoring is essential for continuous evaluation of the patient’s volume status, ![]() especially in patients older than 50 years or those with chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, or hepatic disease. Overaggressive volume resuscitation may result in fluid volume excess with complications of cardiac failure and pulmonary edema. Electrolyte levels should be closely monitored, especially in patients with renal or hepatic disease.

especially in patients older than 50 years or those with chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, or hepatic disease. Overaggressive volume resuscitation may result in fluid volume excess with complications of cardiac failure and pulmonary edema. Electrolyte levels should be closely monitored, especially in patients with renal or hepatic disease.

Proton-pump inhibitors deactivate the enzyme system that pumps hydrogen ions from parietal cells thereby inhibiting gastric acid secretion. They have become the preferred agent for erosive ulcer disease with bleeding. Their acid-inhibitory effects are significantly stronger than H2-receptor antagonists. Intravenous (IV) PPIs or high-dose oral PPIs following a bleeding episode are effective in reducing rebleed, the number of transfusions, and the need for further endoscopic therapy.

CARE PLANS FOR ACUTE GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

related to active loss secondary to hemorrhage from the GI tract

Electrolyte and Acid-Base Balance; Fluid Balance

1. Monitor BP every 15 minutes during episodes of rapid, active blood loss or unstable vital signs. Be alert to MAP decreases of greater than 10 mm Hg from previous reading.

2. Monitor postural vital signs on patient’s admission, every 4 to 8 hours, and more frequently if recurrence of active bleeding is suspected: measure BP and HR with patient in a supine position, followed immediately by measurement of BP and HR with patient in a sitting position (as tolerated). A decrease in systolic BP greater than 10 mm Hg or an increase in HR of 10 bpm with patient in a sitting position suggests a significant intravascular volume deficit, with approximately 15% to 20% loss of volume.

3. Monitor HR, ECG, and cardiovascular status hourly, or more frequently in the presence of active bleeding or unstable vital signs. Be alert to a sudden increase in HR, which suggests hypovolemia.

4. Measure central pressures and thermodilution CO every 1 to 4 hours. Be alert to low or decreasing CVP, PAOP, and CO. Calculate SVR every 2 to 4 hours, or more frequently in patients whose condition is unstable. An elevated HR, decreased PAOP, decreased CO (CI less than 2.5 L/min/m2), and increased SVR suggest hypovolemia and the need for volume restoration.

5. Measure urinary output hourly. Be alert to output less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr for 2 consecutive hours. Increase fluid intake or consider fluid bolus if decreased output is caused by hypovolemia and hypoperfusion.

1. Obtain two large-bore IV lines (16- or 18-gauge) and central venous access.

2. Initiate crystalloid replacement therapy with a combination of normal saline and lactated Ringer. Fluid should be warmed to prevent hypothermia.

3. Administer packed red blood cells (PRBCs) for persistently low Hct (less than 20% to 25%). Anticipate Hct will increase by 3% following 1 unit of PRBCs.

4. Fresh-frozen plasma is required after 10 units of packed RBCs is infused.

5. Monitor prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT); administer fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) to maintain normal levels.

6. Monitor ionized calcium levels closely because of calcium’s tendency to bind with citrate. Administer calcium gluconate for ionized calcium levels less than 4.4 mg/dl.

7. Prepare for platelet transfusion if platelets fall below 50,000 or following 10 units of packed RBCs.

1. Initiate fluid replacement (see Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances, p. 37).

2. Collaborate with physician or midlevel practitioner to administer vasoactive medication if shock persists with volume resuscitation.

3. Monitor for cerebral ischemia or indications of insufficient cerebral blood flow.

4. Monitor renal function (BUN and creatinine levels for elevations) as intravascular volume depletion can lead to prerenal azotemia.

5. Monitor tissue oxygenation using ABG, SvO2, central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) monitoring if available, and serum lactate measurements.

6. Monitor ECG for ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion, which may be seen as a result of the shock state.

Bleeding reduction: gastrointestinal

1. Administer proton-pump inhibitors IV at least 3 days in patients whose endoscopic stigmata suggest a high risk of rebleeding. Vasopressin (Pitressin), or Terlipressin (Glypressin) may help slow variceal bleeding.

2. Measure and record all GI blood losses from hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena.

3. Check all stools and gastric contents for occult blood.

4. Ensure proper function and patency of gastric tubes. Do not occlude the air vent of double-lumen tubes, because this may result in vacuum occlusion. Confirm placement of gastric tube at least every 8 hours, and reposition as necessary. Inflated esophageal balloon tubes used for tamponade of varices must be secured and stable.

5. Initiate nasogastric lavage to clear the stomach of blood. Gastric lavage does not slow or stop bleeding as once thought but is necessary prior to endoscopy for optimal visualization.

6. Teach patient signs and symptoms of actual or impending GI hemorrhage: pain, nausea, vomiting of blood, dark stools, lightheadedness, and passage of frank blood in stools. Reinforce the importance of seeking medical attention promptly if signs of bleeding occur.

7. Teach patient the importance of avoiding medications/agents with the potential for gastric irritation: aspirin, NSAIDs, ethanol.

related to decreased preload secondary to acute blood loss

Within 8 hours of this diagnosis, CO approaches normal limits with adequate tissue perfusion as evidenced by CI greater than 2.5 L/min/m2, MAP greater than 70 mm Hg, CVP 2 to 6 mm Hg, urinary output greater than 0.5 ml/kg/hr, normal sinus rhythm on ECG, distal pulses greater than 2+ on a 0 to 4+ scale, and brisk capillary refill (less than 2 seconds).

1. Administer vasopressors and inotropic agents as prescribed if tissue perfusion remains inadequate following intravascular volume replacement.

2. Monitor ECG for evidence of myocardial ischemia (i.e., T-wave depression, QT prolongation, ventricular dysrhythmias).

3. Monitor for physical indicators of diminished cardiac output, including pallor, cool extremities, capillary refill greater than 2 to 3 seconds, and decreased or absent amplitude of distal pulses.

4. Monitor vital signs and CO, and replace volume as indicated (see Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances, p. 37).

5. Monitor for oliguria hourly; report urine output less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr for 2 consecutive hours.

1. Administer oxygen via nasal cannula or facemask to facilitate maximal oxygen delivery.

2. Monitor pulse oximetry and ABG values for hypoxemia. Report arterial PaO2 less than 80 mm Hg and oxygen saturation below 92%.

3. Prepare for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation if patient is distressed with oxygen saturation less than 90% with supplemental oxygen.

4. Monitor for respiratory crackles, which can result from overaggressive fluid resuscitation.

![]() Cardiac Care: Acute; Oxygen Therapy; Invasive Hemodynamic Monitoring; Dysrhythmia Management

Cardiac Care: Acute; Oxygen Therapy; Invasive Hemodynamic Monitoring; Dysrhythmia Management

1. Monitor and document presence of abdominal pain or discomfort. Devise a pain scale with patient. Pain may disappear during a bleeding episode since blood covers and protects eroded tissue.

2. Administer gastric alkalizing agents and sucralfate as prescribed to relieve pain caused by upper GI disorders. Hold these agents prior to endoscopy.

3. Measure gastric pH at least every 4 hours. For gastric aspirate, use a clean syringe and discard the first aspirate to ensure accuracy. Some may use nasogastric (NG) tonometer to measure gastric mucosal pH.

4. Adjust gastric alkalizing therapy to maintain pH of 4.0 to 5.0 or other prescribed range. Avoid excessive alkalization, which is associated with increased risk of nosocomial pneumonia.

5. Administer opiate analgesics with caution to hypovolemic patients to avoid hypotension and respiratory depression.

6. Supplement analgesics with nonpharmacologic maneuvers to aid in pain reduction. Patients who have pain associated with gastric reflux may be more comfortable with the head of the bed (HOB) elevated, if this position does not compromise hemodynamic status. Reflux may prompt variceal bleeding.

![]() Analgesic Administration; Distraction; Environmental Management; Vital Signs Monitoring

Analgesic Administration; Distraction; Environmental Management; Vital Signs Monitoring

related to irritation and increased motility secondary to the presence of blood in the GI tract

Fluid Balance; Bowel Elimination; Electrolyte and Acid-Base Balance

1. Monitor and record the amount, frequency, and character of patient’s stools.

2. Provide or have bedpan or bedside commode (only for hemodynamically stable patients) readily available. Consider use of a contained stool management device (e.g., Flexiseal.)

3. Minimize embarrassing odor by removing stool promptly and using room deodorizers.

4. Use matter-of-fact approach when assisting patient with frequent bowel elimination. Reassure patient that frequent elimination is a common problem for most patients with GI bleeding.

5. Evaluate bowel sounds every 4 to 8 hours. Anticipate normal to hyperdynamic bowel sounds. Absence of bowel sounds (especially in association with severe pain or abdominal distention) may signal serious complications such as ileus or perforation.

6. Report abnormal serum sodium, potassium, and calcium levels to physician or midlevel practitioner.

Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

1. Collaborate with physician, midlevel practitioner, dietitian, and pharmacist to estimate patient’s individual metabolic needs on the basis of activity level, underlying disease process, and nutritional status before hospitalization.

2. Provide parenteral nutrition during acute phase of the bleeding, as prescribed.

3. Begin enteral therapy when acute hemorrhagic episode has subsided and bowel function has returned.

4. Monitor thyroxine-binding prealbumin, and report decreasing levels.

5. Weigh patient daily at the same time of day, using the same scale. Weight can be a practical indicator of nutritional status if patient’s weight changes are interpreted on the basis of the following factors: fluid shifts (edema, diuresis, third spacing), surgical resection, and weight of dressings and equipment.

Acute pancreatitis

Pathophysiology

Normally, pancreatic acinar cells produce and secrete proteolytic enzymes in their inactive form. These proenzymes travel through the pancreatic duct safely until reaching the duodenum, where they are converted to active form by other enzymes found in the intestinal brush border. In AP, the proenzyme trypsinogen is prematurely activated to the proteolytic enzyme trypsin within the acinar cells of the pancreas. Once secreted into the pancreatic duct, trypsin converts other proenzymes into active forms, resulting in enzymatic autodigestion of the pancreas. The exact mechanisms by which trypsin becomes prematurely activated remains unanswered. Activated digestive enzymes within the pancreas not only digest pancreatic tissue, leading to inflammation, capillary leakage, and necrosis, but also digest elastin in blood vessel walls, causing vascular injury and hemorrhage. Inflammatory mediators (kinins, complement, coagulation factors) released at the site of tissue and vessel injury cause further edema, inflammation, thrombosis, and hemorrhage.

The most common causes of AP are alcoholism and gallstones (75% of all cases). Alcohol may have a direct toxic effect on the pancreatic acinar cells or may cause inflammation of the sphincter of Oddi, resulting in the retention of enzymes in the pancreatic duct. In patients with gallstones, the hypothesized mechanism is obstruction of the pancreatic duct by gallstones, as the pancreatic duct and the common bile duct share the same outlet into the duodenum. This obstruction causes bile to reflux into the pancreatic duct. Hypercalcemia, hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypothermia are all associated with the development of acute pancreatitis. Other causes or associations of AP include endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedure, blunt or penetrating trauma, metabolic factors, infectious agents, and certain drugs (Box 9-3). Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued information for health care professionals identifying occurrences of AP in type 2 diabetic patients using the antidiabetic drug exenatide. The FDA is working to include stronger and more prominent warnings on the label. The cause of AP remains unknown in about 15% of all cases even with thorough investigation.

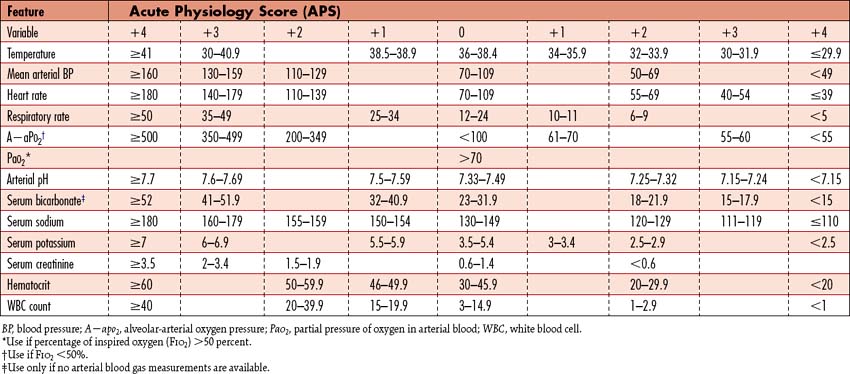

It is important to identify those patients at risk for SAP to rapidly implement appropriate recourses. Ranson criteria provide a scale of severity for acute pancreatitis based on age and laboratory studies. Pancreatitis is classified as severe when three or more of Ranson criteria are met during the first 48 hours following presentation (Box 9-4). Mortality is approximately 16% to 20% with 3 or 4 positive criteria, 40% with 5 or 6 positive criteria, and 100% with 7 or 8 criteria. A contrast-enhanced CT scoring system is also available to assist with diagnosis, in which the severity is graded using CT findings. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scoring system (Table 9-3) is another tool to determine severity. An APACHE II point score of less than 8 within the first 48 hours coincides with survival. Higher scores during this time interval reflect increased morbidity and mortality rates. These multiple factor scoring systems do carry a false-positive rate and should be used in conjunction with ongoing clinical findings and other laboratory data.

Box 9-4 RANSON CRITERIA FOR CLASSIFYING THE SEVERITY OF PANCREATITIS

Ranson’s Criteria Scoring Mechanism

Complications

A major complication of SAP is marked depletion of intravascular plasma volume, the result of fluid sequestration into the interstitium, retroperitoneum and the gut. Massive, life-threatening hemorrhage from rupture of necrotic tissue results in serious blood volume depletion. SIRS ensues, wherein inflammatory mediators trigger vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, which further contributes to severe hypovolemia and hypotension. Hypoalbuminemia is frequently present, which prompts intravascular fluids to move through the permeable capillaries more rapidly since oncotic pressure is reduced. Severe hypotension may persist despite volume repletion. If hypovolemia is not adequately corrected promptly, acute renal failure may develop, as the patient progresses through the stages of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and organs begin failing (see SIRS, Sepsis and MODS, p. 924).

Mild-to-severe respiratory failure with hypoxemia is common, as is the case with all patients with SIRS. Respiratory complications are related to right-to-left vascular shunting within the lung and alveolar-capillary leakage caused by the circulating inflammatory mediators resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (see Acute Lung Injury and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, p. 365). In addition, elevation of the diaphragm, atelectasis, and pleural effusion caused by subdiaphragmatic inflammation of the pancreas and surrounding tissues can compromise ventilation further. Inflammatory mediators and vascular injury can also cause intravascular coagulopathy, resulting in life-threatening complications such as major thrombus formation, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), and pulmonary emboli. The circulatory and respiratory failure that ensue are often the cause of death in these patients.

The formation of pancreatic pseudocysts (encapsulated fluid collections with high enzyme content) is common in SAP patients monitored by CT scans. Pseudocysts can appear anywhere but are usually found within or adjacent to the pancreas. Pseudocysts frequently become infected requiring drainage or they may become hemorrhagic.

Assessment

Goal of system assessment: acute pancreatitis

Evaluate for organ and systemic involvement of dysfunctional pancreatic secretions.

Abdominal pain

• Sudden onset of abdominal pain (often after excessive food or alcohol ingestion) lasting 12 to 48 hours, described as mild discomfort to severe distress, and located from the midepigastrium to the right upper quadrant (RUQ). Occasionally pain is reported in the left upper quadrant.

• The pain is typically described as boring and deep.

• The pain may radiate to the back.

• Nausea, vomiting, and restlessness typically accompany the pain; diarrhea, melena, and hematemesis may also be present.

Observation

• Mild-to-moderate ascites is present.

• Dyspnea and cyanosis may be observed if ARDS is present (see Acute Lung Injury and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, p. 365).

• Jaundice may be present with biliary tract disease.

• Grey Turner sign (flank discoloration) and Cullen sign (umbilical area discoloration) occur in about 1% of cases and are associated with a poor prognosis.

• With severe hypocalcemia, Chvostek sign (facial twitching after a facial tap) or Trousseau sign (hand spasms when BP cuff inflates) may be elicited. Hypocalcemia causes numbness or tingling in the extremities that progresses to tetany if calcium is severely depleted.

Auscultation

• Diminished or absent bowel sounds reflective of GI dysfunction and paralytic ileus.

• Breath sounds may be decreased or absent, suggesting focal atelectasis or pleural effusion. Effusions are usually left-sided but can be bilateral. Auscultation of crackles reflects hypoventilation caused by pain, early ARDS, or microemboli.

Palpation

• Abdominal tenderness is common.

• Abdominal palpation will reveal localized tenderness in the RUQ or diffuse discomfort over the upper portion of the abdomen without rigidity or rebound.

• An upper abdominal mass may be palpated due to the inflamed pancreas or a pseudocyst.

• In the presence of hemorrhage or severe hypovolemia, hands are cool and sweaty to touch.

• Peripheral pulses will be diminished and capillary refill delayed with hemorrhage or severe hypovolemia.

Hemodynamic measurements for complications of sap

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Studies | ||

| Complete blood count (CBC) White blood cell (WBC) count Red blood cell (RBC) count Hemoglobin (Hgb) Hematocrit (Hct) Platelets |

Assess for inflammation and infection. Platelets may be consumed if inflammation is severe enough to prompt DIC. Reflective of volume status and oxygen carrying capacity. |

Leukocytosis with a WBC count of 11,000–20,000/mm3 is reflective of the acute inflammatory process and not bacterial infection. Bacterial infection may ensue in a small percentage of patients reflecting a WBC count >20,000/mm3. Hct and Hgb levels vary, depending on the presence of hemorrhage (decreased) or dehydration (increased). |

| Serum amylase Serum lipase |

Cardinal finding consistent with AP, although not diagnostic. Amylase rises almost immediately but can return to normal within 48–72 hours. Lipase remains elevated for 14 days and is a more sensitive test than amylase. | Serum elevations in amylase or lipase levels >3 times the upper normal limit, in the absence of renal failure, are most consistent with acute pancreatitis. Serum lipase is more specific for AP and is preferred. |

| Serum calcium | Assesses for hypocalcemia. Some calcium is protein-bound; serum levels depend on albumin levels. As serum albumin levels decrease with intravascular fluid losses, reductions in serum calcium levels will follow. | Calcium levels may fall to <8 mg/dl predisposing the patient to tetany and other complications of hypocalcemia. In SAP, serum calcium levels may decrease dramatically as calcium binds with free fatty acids released during lipolysis of peripancreatic fat tissue. |

| Serum glucose | Assesses for hyperglycemia as a determinant of injury to pancreatic islet cells. | Blood glucose values are commonly >200 mg/dl. |

| Serum triglyceride | Assess for possible cause of AP. | Serum triglyceride levels >1000 mg/dl are found to be a causative factor of AP. |

| Serum creatinine | Evaluates renal function | Levels >1.5 mg/dl are seen in patients with acute renal failure. |

| Electrolytes Serum potassium Serum magnesium Serum bicarbonate |

Assess levels closely during fluid resuscitation. | Hyperkalemia is present initially due to significant cellular damage releasing large amounts of K+ into circulation and increases with acidosis associated with shock. Increased serum bicarbonate and hypokalemia values reflect metabolic alkalosis later, usually the result of fluid therapy, vomiting or gastric suctioning. Hyponatremia and hypomagnesemia will be seen with vomiting and fluid sequestration. |

| Liver function tests (LFTs) Serum bilirubin Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) |

Assesses liver involvement and distinguish between alcohol-induced and gallstone induced disease. | Persistent elevation of liver enzymes suggests hepatic inflammation caused by alcohol ingestion or viral hepatitis. Elevated total bilirubin levels and ALP value >150 IU/L are suggestive of biliary disease. |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | Assesses for severe inflammation. CRP is a nonspecific acute-phase reactant of inflammation that is suggestive of severe acute pancreatitis | A CRP level >150 mg/L at 48 hours after disease onset is suggestive of pancreatic necrosis. |

| Coagulation studies | Assesses the extent of coagulopathic involvement as inflammatory mediators trigger the coagulation cascade. In SAP, DIC may develop. | Decreases in platelets and fibrinogen will be present as they are rapidly consumed. Elevations in circulating levels of fibrin are associated with microthrombi in the pancreas and other tissues. |

| Arterial blood gas (ABG) | Assesses oxygenation status and acid-base balance | Decreased arterial oxygen tension is a common finding and may be present without other symptoms of pulmonary insufficiency. Early hypoxia produces a mild respiratory alkalosis. Arterial oxygen saturation may be diminished. |

| Nutrition profile Serum albumin Serum transferrin serum Prealbumin Total lymphocyte count (TLC) |

Assesses nutritional status to identify preexisting malnutrition and to guide nutrition replacement therapy. | Decreased albumin, transferrin, and TLC are indicative of malnutrition and seen in patients with alcoholic disease. Prealbumin levels will rise with effective therapy. |

| Noninvasive Cardiology | ||

| ECG | Assess and monitor for cardiac rhythm disturbances. | ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion may be seen as a result of the shock state, the severe pain that causes coronary artery spasm, or the effect of trypsin and bradykinins on the myocardium. Hypocalcemia results in widening of the ST segment. |

| Radiology | ||

| Radiography Abdominal radiograph Chest radiograph |

Abdominal x-rays assess for bowel dilation. Chest x-rays identify pulmonary involvement. |

Abdominal radiograph identifies dilation of the bowel and ileus. Chest radiograph distinguishes effusions from atelectasis and identifies characteristic infiltrates consistent with ARDS. |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan | Estimates size of the pancreas; identifies fluid collection, cystic lesions, abscesses, and masses; visualizes biliary tract abnormalities; and monitors inflammatory swelling of the pancreas. The CT scan can determine the presence or extent of necrosis, and thus serves as an indicator of disease severity. | Enlarged pancreas, dilation of the common bile duct and evidence of gallstones when present. CT confirms the diagnosis of AP. |

| Endoscopic ultrasonography | Used to visualize the opening to the pancreas when a biliary cause of AP is suspected, to observe for swelling, ductal abnormalities, and presence of tumors or stones. | If these conditions are present, ERCP should not be used as it may worsen the condition. |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) | Used to relieve obstruction caused by stone impaction | Not indicated for diagnosis of SAP as it may aggravate inflammation |

Collaborative management

Management includes monitored supportive care, efforts to prevent, limit and treat complications, and recurrences. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)’s guidelines “Management of Acute Pancreatitis” frame the care priorities. Because AP is a disease of significant variability, there is a paucity of large randomized controlled trials. The AGA recommendations (Box 9-5) are therefore based on available scientific studies and evidence with expert opinion.

Box 9-5 AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGY ASSOCIATION (AGA) RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACUTE PANCREATITIS (AP)

Assessment of severity

• Severe disease is defined by mortality, the presence of organ failure, and/or local pancreatic complications (pseudocyst, necrosis, abscess).

• Prediction of severe disease is achieved with the combination of clinical assessment, a multiple factor scoring system and imaging studies. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II System is preferred.

• If severe disease is predicted, a contrast-enhanced CT should be performed at 72 hours to assess the degree of pancreatic necrosis.

Determination of etiology

• Establish etiology in at least three-fourths of all patients.

• Admission labs should include amylase, lipase, triglycerides, calcium, and liver chemistries. Ultrasonography should be performed for biliary disease.

• For patients with unexplained pancreatitis less than 40 years of age, extensive or invasive testing is not recommended.

Management

• Provide vigorous fluid resuscitation, supplemental oxygen, correction of electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities, pain control, and nutritional support.

• ERCP should be performed early in patients with gallstone pancreatitis with cholangitis. ERCP should only be performed by endoscopists with appropriate training.

• No recommendation for antibiotic prophylaxis can be made for sterile necrosis. If used, antibiotics should be restricted for only patients with pancreatic necrosis of greater than 30% of the gland by CT.

• Fluid collections and pseudocysts require no therapy unless infected.

• Consider surgical therapy and antibiotics for infected necrosis.

Prevent recurrences by referring those with alcoholic pancreatitis to counseling and patients with gallstone pancreatitis for surgical removal.

Data from the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) Institute: Medical position statement on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 132:2019–2021, 2007.

Care priorities for severe acute pancreatitis

3. Correct electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities.

Hypocalcemia commonly occurs in patients with SAP and is a marker of poor prognosis. Ionized levels should be monitored, since with low albumin levels, the amount of measured protein-bound calcium is falsely low. If levels are low or if the patient develops signs of neuromuscular instability, replace with calcium chloride. Because hypercalcemia is a cause of AP, calcium replacement is prescribed cautiously. Ensure magnesium and albumin levels are adequate.

4. Provide effective pain control.

Acute abdominal pain is caused by peritoneal irritation from the inflamed pancreas. Opioid analgesics are administered for relief of severe pain. Continuous or intermittent IV therapy is used, depending on the severity of the pain. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a helpful mode of delivery. Morphine has been implicated in the past as causing spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, thus worsening the pancreatitis. However, no evidence has been found to demonstrate this in humans. Meperidine was the analgesic of choice but has an active neurotoxic metabolite that accumulates![]() with long-term use, causing agitation, seizures, and muscle fibrosis. Because of these side effects, many hospitals have limited the availability of IV meperidine. Hydromorphone is the preferred alternative, recommended by the AGA.

with long-term use, causing agitation, seizures, and muscle fibrosis. Because of these side effects, many hospitals have limited the availability of IV meperidine. Hydromorphone is the preferred alternative, recommended by the AGA.

5. Initiate nutritional support.

Nutritional supplementation should be considered early to promote tissue repair in patients with SAP as they are unable to tolerate eating for several days. Enteral feedings are preferred over TPN today. Enteral nutrition (EN) may be started within the first 48 hours of admission for the patient with or predicted SAP. Pancreatic secretions are not stimulated with the delivery of enteral elemental nutrition into the mid or distal jejunum, so jejunal feedings are possible for patients with SAP. Weighted NG tubes or NJ tubes should be positioned beyond the ligament of Treitz. The ligament of Treitz is a musculofibrous band that extends from the ascending part of the duodenum and jejunum to the right crus of the diaphragm and tissue around the celiac artery. Nasojejunal feedings are tolerated in most patients with meticulous attention to feeding tolerance and consulting with dieticians and nutritional support pharmacists regarding elemental feedings (see Nutritional Support, p. 117). Feeding into the stomach should be avoided, as this modality is associated with more pulmonary complications and more complications overall. If enteral feedings are not tolerated despite trying elemental feedings into the jejunum, TPN may be required, necessitating insertion of a central IV catheter. TPN continues to be associated with significant complications from the catheter, ranging from catheter-related sepsis, local abscess, localized hematomas, pneumothorax, venous thrombosis, venous air embolism, and metabolic complications such as hyperglycemia and electrolyte imbalance. Low-fat oral feedings are begun after the initial episode subsides and bowel function returns.

8. Prevent infection; possibly with prophylactic antibiotics.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent the development of infected necrosis is controversial. The AGA cannot recommend for or against its use. If antibiotics are to be used, they should be restricted for patients with necrosis involving more than 30% of the pancreas evidenced by CT scan and administered for no longer than 14 days. Antibiotic choice must provide adequate penetration of necrotic tissue, such as imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem, or a combination of a quinolone and metronidazole. For infected necrosis, pseudocysts or abscesses, the antibiotic should be tailored to the infecting organism.

CARE PLANS FOR ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Electrolyte and Acid-Base Balance; Fluid Balance

1. Administer crystalloids, colloids, or a combination of both as prescribed.

2. Monitor BP every 1 to 4 hours if losses are caused by fluid sequestration, inadequate intake, or slow bleeding. Monitor BP continuously with arterial line, or hourly and increase to every 15 minutes if patient has active blood loss or massive fluid sequestration.

3. Monitor HR and cardiovascular status at least every 2 to 4 hours, and more often with SAP.

4. Measure urinary output hourly. Report output less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr for 2 consecutive hours. Evaluate intravascular volume and cardiovascular function, and increase fluid intake promptly if decreased urinary output is caused by hypovolemia and hypoperfusion.

5. Monitor for indicators of hypovolemia, including cool extremities, delayed capillary refill (more than 2 seconds), and decreased amplitude of or absent distal pulses.

6. Estimate ongoing fluid losses. Measure all drainage from tubes, catheters, and drains. Note the frequency of dressing changes because of saturation with fluid or blood. Compare 24-hour urine output with 24-hour fluid intake, and record the difference.

7. Administer room temperature IV fluids. Aggressive IV hydration with volumes of 250 to 300 ml/hr of crystalloids may be necessary in patients with no cardiac history.

8. Continuously monitor HR and ECG. Be alert to increases in HR, which suggest hypovolemia.

9. Monitor cardiovascular status hourly including CVP.

10. Measure hemodynamic parameters (i.e., CVP, CO) and thermodilution CO every 1-4 hours or continuously using an arterial based system (e.g., Flotrac or PICO). Be alert to low or decreasing CVP, and CO in patients with borderline cardiac function or respiratory function. An elevated HR, decreased CVP, and decreased CO (CI less than 3 L/min/m2) suggest hypovolemia.

11. Consider fluid bolus for urine output less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr for 2 consecutive hours. If SAP is present, initiate fluid resuscitation and shock management.

1. Obtain and maintain large-bore IV and central venous access.

2. Administer IV fluids; crystalloids are preferred (see Fluid Management, above).

3. Administer PRBCs for Hct less than 25%. Anticipate an Hct increase of 3% following 1 unit of PRBCs.

4. Consider administering albumin for serum albumin less than 2 g/dl, but observe for worsening of edema if capillary leak is severe.

5. Monitor coagulation studies and CBC.

6. Administer fresh-frozen plasma for coagulopathy and to replace lost circulating proteins.

7. Assess for signs of overaggressive fluid resuscitation (see Fluid Volume Excess, p. 776).

8. Weigh patient daily, using the same scales and method. Weight may increase due to significant capillary leak and anasarca with intravascular volume depletion.

9. Evaluate character of all fluids lost. Note color and odor. Be alert to the presence of particulate matter, fibrin, and clots. Test GI aspirate, drainage, and excretions (including stool) for the presence of occult blood.

1. Monitor fluid status (see Fluid Management, Fluid Resuscitation, p. 773).

2. Collaborate with physician or midlevel practitioner to administer vasoactive medication if shock persists with volume resuscitation.

3. Monitor for cerebral ischemia or indications of insufficient cerebral blood flow.

4. Monitor renal function (BUN and creatinine levels for elevations) as intravascular volume depletion can lead to prerenal azotemia.

5. Monitor tissue oxygenation using arterial blood gas, SvO2 or ScvO2 monitoring and serum lactate measurements.

6. Monitor ECG for ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion, which may be seen as a result of the shock state.

1. Monitor for manifestations of electrolyte imbalance. Calcium, sodium, magnesium, and potassium are lost with fluid sequestration and vomiting.

2. Maintain IV solutions containing electrolytes at a constant rate.

3. Continuously monitor ECG for alterations related to electrolyte imbalances.

4. Monitor ionized calcium. Widening of the QT interval suggests severe hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemia may produce numbness or tingling in the extremities that can progress to tetany.

5. Administer calcium gluconate or calcium chloride for low ionized calcium (less than 4.4 mg/dl). Calcium chloride will provide a higher level of calcium replacement given the strength and chemical composition.

6. Monitor T wave as a sign of alterations in serum potassium levels.

1. Restore acceptable preload by correcting hypovolemia (see preceding nursing diagnosis, Fluid Volume Deficit).

2. Administer inotropic agents. Consider dobutamine for myocardial contractile support. Monitor hemodynamic parameters carefully to observe for vasodilation if dose of dobutamine is low.

3. Space out procedures and treatments to allow long periods (at least 90 minutes) of uninterrupted rest.

4. Minimize anxiety-producing situations, and assist patient with reducing anxiety.

![]() Care: Acute; Shock Management; Cardiac: Dysrhythmia Management; Anxiety Reduction; Energy Management

Care: Acute; Shock Management; Cardiac: Dysrhythmia Management; Anxiety Reduction; Energy Management

Pain Control; Pain Level; Comfort Level

1. As prescribed, administer IV opiate analgesic before pain becomes severe.

2. ![]() Meperidine may be used initially for up to 3 days, but should not be administered long-term due to metabolite accumulation which can cause neurological adverse effects. Meperidine is avoided in SAP patients, since analgesia is needed for more than 3 days. Hydromorphone may be a better alternative.

Meperidine may be used initially for up to 3 days, but should not be administered long-term due to metabolite accumulation which can cause neurological adverse effects. Meperidine is avoided in SAP patients, since analgesia is needed for more than 3 days. Hydromorphone may be a better alternative.

3. Monitor HR and BP at least every 4 hours, and at least every 2 hours with SAP patients. Opiates cause vasodilation and can add to the serious hypotension SAP patient with volume depletion. Monitor every 15 minutes if severe pain is uncontrolled. Consult with physician or midlevel practitioner for changes in analgesic medications and dosages.

4. Evaluate effectiveness of medication, and consult physician or midlevel practitioner for dose and drug manipulation.

5. Consider continuous infusion or PCA for more effective pain control.

6. Consider epidural route if IV route is ineffective.

7. If medications are not effective, prepare patient for splanchnic block or other pain-relieving procedure.

8. Assess for anxiety and consider sedatives in conjunction with analgesia.

9. Monitor respiratory pattern and level of consciousness (LOC) closely because both may be depressed by the large amounts of opiate analgesics usually required to control pain.

1. ![]() Pancreatitis can be very painful. Prepare significant others for personality changes and behavioral alterations associated with extreme pain and opiate analgesia. Family members sometimes misinterpret patient’s lethargy or unpleasant disposition and may even blame themselves. Reassure them that these are normal responses.

Pancreatitis can be very painful. Prepare significant others for personality changes and behavioral alterations associated with extreme pain and opiate analgesia. Family members sometimes misinterpret patient’s lethargy or unpleasant disposition and may even blame themselves. Reassure them that these are normal responses.

2. Supplement analgesics with nonpharmacologic maneuvers to aid in pain reduction. Modify patient’s body position to optimize comfort. Many patients with abdominal pain find a dorsal recumbent or lateral decubitus bent-knee position most comfortable.

3. Consider cultural influences on pain response.

4. Because anxiety reduction contributes to pain relief, ensure consistency and promptness in delivering analgesic.

5. Patients and family members sometimes are distressed at the health team members’ inability to relieve pain. Provide continual reassurance that all possible measures are being implemented.

Respiratory Status: Gas Exchange; Respiratory Status: Ventilation

1. Administer oxygen via nasal cannula to maintain an oxygen saturation greater than 95%. Check oxygen delivery system at frequent intervals to ensure proper delivery.

2. Monitor and document respiratory rate every 1 to 4 hours as indicated. Note pattern, degree of excursion, and whether patient uses accessory muscles of respiration. Consult physician for significant deviations from baseline.

3. Auscultate both lung fields every 4 to 8 hours. Note presence of abnormal sounds (crackles, rhonchi, wheezes) or diminished sounds.

4. Be alert to early signs of hypoxia, such as restlessness, agitation, and alterations in mentation.

5. ![]() Monitor SaO2 via continuous pulse oximetry or frequent ABG values during the first 48 hours. Many patients with pancreatitis do not have obvious clinical symptoms of respiratory failure, and a decreased arterial oxygen tension may be the first sign of ARDS or failure. Consult physician or midlevel practitioner if PaO2 is less than 60 to 70 mm Hg or if oxygen saturation falls below 92%.

Monitor SaO2 via continuous pulse oximetry or frequent ABG values during the first 48 hours. Many patients with pancreatitis do not have obvious clinical symptoms of respiratory failure, and a decreased arterial oxygen tension may be the first sign of ARDS or failure. Consult physician or midlevel practitioner if PaO2 is less than 60 to 70 mm Hg or if oxygen saturation falls below 92%.

6. Maintain a body position that optimizes ventilation and oxygenation. Elevate HOB 30 degrees or higher, depending on patient’s comfort. If pleural effusion or other defect is present on one side, position patient with the unaffected lung dependent to maximize the ventilation-perfusion relationship.

7. If patient fails to stabilize, prepare for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

8. Monitor SaO2 via continuous pulse oximetry and frequent ABG values during the first 48 hours. Hypoxemia in the absence of preexisting pulmonary disease may be an early sign of ARDS.

9. Pulmonary hypertension is anticipated in patients with ARDS with normal PAOP values.

10. Avoid overaggressive fluid resuscitation (see Fluid Volume Excess, below).

See Acute Lung injury and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, p. 365, for additional information.

related to excessive intake secondary to overaggressive fluid resuscitation

Fluid Overload Severity; Fluid Balance; Electrolyte and Acid-Base Balance

1. ![]() Evaluate patient every 1 to 2 hours for clinical indicators of fluid volume excess: dyspnea, orthopnea, increased respiratory rate and effort, S3 gallop, or crackles. Document and report changes and new findings.

Evaluate patient every 1 to 2 hours for clinical indicators of fluid volume excess: dyspnea, orthopnea, increased respiratory rate and effort, S3 gallop, or crackles. Document and report changes and new findings.

2. Consider administering furosemide (Lasix) or other diuretic as prescribed to promote diuresis, but only after volume status has been carefully evaluated. Patients may be intravascularly hypovolemic despite significant weight gain resulting from third spacing of fluids. Diuresis may not prove to be beneficial. Document response to diuretic therapy by noting onset and amount of diuresis.

![]() Fluid/Electrolyte Management, Fluid Monitoring, Hemodynamic Regulation

Fluid/Electrolyte Management, Fluid Monitoring, Hemodynamic Regulation

Infection Severity; Immune Status

1. Check temperature every 4 hours for increases. Be aware that hypothermia may precede hyperthermia in some patients.

2. Temperature may be slightly elevated due to the inflammatory process. If temperature remains elevated for longer than 1 week suspect the patient may have developed bacterial necrosis.

3. If temperature suddenly rises, obtain specimens for culture of blood, sputum, urine, and other sites as prescribed. Monitor culture reports, and report positive findings promptly.

4. ![]() Evaluate orientation and LOC every 2 to 4 hours. Report significant deviations from baseline.

Evaluate orientation and LOC every 2 to 4 hours. Report significant deviations from baseline.

5. Monitor BP, HR, RR, CO, and CVP every 1 to 4 hours. An elevated CO and decreased CVP suggest systemic inflammatory response or sepsis. Be alert to increases in HR and RR associated with temperature elevations.

6. Monitor WBC and anticipate a mild leukocytosis of 11,000 to 20,000/mm3 due to the inflammatory response of SAP. If WBC count is greater than 20,000/mm3, suspect infected pancreatitis. If total WBC count is elevated, monitor WBC differential for an elevation of bands (immature neutrophils).

7. Prophylactic antibiotics are NOT recommended for sterile pancreatitis unless the pancreas is greater than 30% necrosed as evidenced by CT scan.

8. If prescribed, administer parenteral antibiotics in a timely fashion. Reschedule antibiotics if a dose is delayed for more than 1 hour. Recognize that failure to administer antibiotics on schedule can result in inadequate blood levels and treatment failure.

9. Do not administer prophylactic antibiotics for SAP for longer than 14 days.

10. Patients with infected pancreatitis evidenced by aspirates positive for bacteria on gram stain or culture require antibiotic therapy and may undergo surgical debridement.

![]() Medication Management; Vital Signs Monitoring; Temperature Regulation; Intravenous (IV) Therapy

Medication Management; Vital Signs Monitoring; Temperature Regulation; Intravenous (IV) Therapy

Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

Patient maintains baseline body weight and demonstrates a positive nitrogen balance.

Nutritional Status; Nutritional Status: Food and Fluid Intake

1. Collaborate with physician, dietitian, and pharmacist to estimate patient’s individual metabolic needs, based on activity level, presence of infection or other stressor, and nutritional status before hospitalization. Overuse of calcium supplements can cause AP; this mechanism should be added as noted above. Develop a plan of care accordingly.

2. Determine preexisting malnutrition with a nutritional assessment.

3. If the patient’s condition improves after 48 hours of resting the bowel, oral intake of clear liquids can be slowly started. Mild to moderate increases in serum amylase and lipase may be noted. Feedings should continue unless these elevations are threefold above normal range.

4. If the patient’s condition does not improve after 48 hours of bowel rest, administer elemental enteral feedings via NJ feeding tube or jejunostomy as prescribed. Pancreatic secretions are not stimulated with the delivery of enteral elemental nutrition into the mid or distal jejunum. Ensure tube placement beyond the ligament of Treitz.

5. Monitor bowel sounds every 4 hours. Document and report deviations from baseline. Withhold jejunal feedings if bowel sounds are absent unless elemental feedings are used.

6. Monitor blood glucose levels every 4 to 8 hours or as prescribed. Treat blood glucose levels greater than 180 mg/dl with insulin therapy.

7. If enteral feedings are not tolerated, begin TPN as prescribed. Monitor closely for evidence of hyperglycemia (e.g., Kussmaul respirations; rapid respirations; fruity, acetone breath odor; flushed, dry skin; deteriorating LOC), which commonly is associated with pancreatitis. Administer insulin as prescribed.

8. Monitor blood glucose levels every 4 to 8 hours or as prescribed. Consult physician or midlevel practitioner for blood levels greater than 180 mg/dl.

9. Begin low-fat oral feedings when acute episode has subsided and bowel function has returned. This may take several weeks in some patients.

related to lack of exposure to health care information

Knowledge: Disease Process; Knowledge Treatment: Regimen

1. Inform patients whose pancreatitis is caused by excessive alcohol intake about the availability of alcohol rehabilitation programs.

2. Teach patient about prescribed medications including drug name, dosage, purpose, schedule, precautions, and side effects.

3. Advise patient about the importance of adhering to a low-fat diet if prescribed.

4. Instruct patient about the indicators of actual or impending GI hemorrhage: nausea, vomiting blood, dark stools, lightheadedness, passing frank blood in stools.

5. Teach the indicators of infection: fever, unusual drainage from surgical incisions or peritoneal lavage site, warmth or erythema surrounding surgical sites, and abdominal pain. Have patient demonstrate oral temperature-taking technique using the type of thermometer that will be used at home.

6. Stress the importance of seeking medical attention promptly if signs of recurrent pancreatitis (i.e., pain, change in bowel habits, passing blood in the stools, or vomiting blood) or infection (see Risk for Infection, p. 776) appear.

![]() Prescribed Activity Exercise, Prescribed Diet, Prescribed Procedure/Treatment, Prescribed Medication; Behavior Modification

Prescribed Activity Exercise, Prescribed Diet, Prescribed Procedure/Treatment, Prescribed Medication; Behavior Modification

Additional nursing diagnoses

As appropriate, see nursing diagnoses and interventions in the following: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (p. 365), Acute Renal Failure (p. 584), and SIRS, Sepsis and MODS, p. 924. Also see Prolonged Immobility (p. 149) and Emotional and Spiritual Support of the Patient and Significant Others (p. 200).

Enterocutaneous fistula

Gastrointestinal assessment: enterocutaneous fistula

History and risk factors

• Direct trauma to the GI system, especially to the bowel

• Infection of surgical wound, drainage tract, or peritoneum

• Prolonged catabolic state in association with bowel injury, GI neoplasm, GI abscess, or severe inflammatory bowel disease

• Complex GI surgical procedures, such as lysis of adhesions for intestinal obstruction or complicated intestinal anastomosis

Abdominal drainage

• Discharge of obvious bile, enteric contents, or gas through a surgical incision

• Sudden increase in the amount of drainage from a surgical incision or drainage catheter

• A change in the nature of drainage from serous or serosanguineous to yellow, green, brown, or foul-smelling

• A change in pancreatic drainage to milky white suggests a pancreatic fistula.

Observation

• ![]() Mental confusion is often present as a result of electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, or early sepsis.

Mental confusion is often present as a result of electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, or early sepsis.

• Sunken eyes, poor skin turgor, and dry oral mucosa, associated with dehydration

• Peripheral edema and muscle wasting related to protein loss

• Erythema, maceration, and edema may be present on the abdomen because of irritating fistula drainage.

Hemodynamic measurements

• Decreased BP, PAP, and CO if severe dehydration is present.

• If early sepsis is present, expect elevated CO and decreased SVR.

• Oxygen demand is increased and may exceed supply. SVO2 will fall without aggressive pulmonary and cardiovascular support.

• The patient will exhibit general hemodynamic instability until fluid balance, inflammation, and infection are controlled.

Diagnostic Tests for Enterocutaneous Fistula

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Studies | ||

| Complete blood count (CBC) White blood cell (WBC) count |

Assess for inflammation, infection, and sepsis | Leukocytosis with WBC count >12,000/mm3. Leukopenia with WBC count <4,000/mm3. Normal WBC with >10% bands. |

| Red blood cell (RBC) count Hemoglobin (Hgb) Hematocrit (Hct) |

Reflective of volume status and oxygen carrying capacity | Hct and Hgb levels will be elevated due to the presence of significant dehydration. Anemia is present due to the prolonged period of illness. |

| Electrolytes Serum potassium Serum magnesium Serum calcium Serum bicarbonate |

Determine accurate electrolyte levels to dictate appropriate replacement as large quantities may be lost through fistula drainage. | Hypokalemia Hypocalcemia Hypomagnesemia Metabolic acidosis |

| Nutrition profile Serum albumin Serum transferrin Serum prealbumin |

Evaluate nutritional status and initiate aggressive nutritional support early. | These labs will vary in individual patients. Serum transferrin levels >140 mg/dl have been shown to correlate with the spontaneous closure of enterocutaneous fistulas thereby reducing mortality among these patients. Levels <140 is a poor prognostic finding. Serum albumin 3 g/dl or less at the time of fistula presentation is a poor prognostic indicator. Prealbumin levels will rise with effective nutritional therapy. |

| Noninvasive Cardiology | ||

| ECG | Assess and monitor for cardiac rhythm disturbances related to hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia | Hypokalemia may result in flattening of the T-wave or U-wave development. Hypocalcemia, hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia can result in widening of the QT interval. |

| Radiology | ||

| Fistulogram Water-soluble contrast medium injected into the suspected fistula |

To identify the anatomy and characteristics of the fistula tract | Radiographs will confirm anatomic site of origin and fistula tract. |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan | CT may be used to identify abscesses associated with fistulization. | Confirmation of intraperitoneal abscess is made. Percutaneous drainage may be performed. |

| Upper GI series | An upper GI series may be indicated if the suspected fistula is proximal to the intestines. | Upper GI series may reveal esophageal, gastric, or duodenal fistulas. |

Nonradiographic evaluation

Bedside maneuver: An external fistula can be simply confirmed without radiology by the oral administration of charcoal. The visible presence of dye in the drainage confirms the presence of a fistula.

Biopsy: In patients with neoplastic disease, a biopsy specimen of the fistula tract may be obtained to determine the presence of malignancy within the tract.

Culture: Fistula effluent from the stomach, duodenum, biliary tree, and pancreas may be cultured for evidence of infection. Small and large bowel fistulas are generally not cultured because of the expected presence of bacteria.

Collaborative management

![]() Early management of ECF presents a considerable challenge requiring advanced support of a multidisciplinary team in a surgical intensive care unit setting. The patient with ECF is typically malnourished with a recent history of malignancy, inflammatory or infectious disease, postoperative or traumatic bowel injury, dehiscence, or inadvertant enterotomy. Their physiologic and nutritional reserves are significantly compromised. This complex set of circumstances are usually complicated by sepsis and the metabolic and fluid derangements caused by the fistula. Early fistula identification is imperative in order to implement appropriate management strategies. Management strategies include patient stabilization, investigation of the fistula, evaluation of surgical need, and the promotion of healing.

Early management of ECF presents a considerable challenge requiring advanced support of a multidisciplinary team in a surgical intensive care unit setting. The patient with ECF is typically malnourished with a recent history of malignancy, inflammatory or infectious disease, postoperative or traumatic bowel injury, dehiscence, or inadvertant enterotomy. Their physiologic and nutritional reserves are significantly compromised. This complex set of circumstances are usually complicated by sepsis and the metabolic and fluid derangements caused by the fistula. Early fistula identification is imperative in order to implement appropriate management strategies. Management strategies include patient stabilization, investigation of the fistula, evaluation of surgical need, and the promotion of healing.

Care priorities

Both somatostatin and its analog octreotide inhibit gastric secretions and thus should decrease fistula output. However, neither drug has shown significant improvement on fistula closure rate or improvement in mortality rates. Additionally, somatostatin is associated with a frequent incidence of hyperglycemia and both drugs are associated with an increased incidence of cholelithiasis. These drugs are therefore not indicated for routine use in patients with ECF. Octreotide alone however, may have limited application in patients with high-output fistulas.

CARE PLANS FOR ENTEROCUTANEOUS FISTULA

1. ![]() Evaluate patient’s fluid balance by calculating and comparing daily intake and output. In patients with high-output fistulas, evaluate total intake and output every 8 hours. Record all sources of output, including drainage from each fistula.

Evaluate patient’s fluid balance by calculating and comparing daily intake and output. In patients with high-output fistulas, evaluate total intake and output every 8 hours. Record all sources of output, including drainage from each fistula.

2. Administer IV crystalloids to replace fistula output. Generally, fistula output is iso-osmotic with high potassium content. Thus, normal saline with potassium is a common choice.

3. Administer albumin for serum albumin less than 2 g/dl. Albumin will assist in restoring plasma oncotic pressure but should be used with caution as it may accumulate in the pulmonary interstitium if the patient has sepsis-induced increased capillary permeability.

4. Consider administering PRBCs for Hct less than 25% unless patient is asymptomatic. Transfusion should be based on the symptoms of the patient. Transfusion of PRBCs will improve oxygen-carrying capacity. Anticipate an Hct increase of 3% following 1 unit of PRBCs.

5. Measure urine output every 1-2 hours. Consult physician or midlevel practitioner if urine output is less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr or if specific gravity increases and urine volume decreases.

6. Assess and document condition of mucous membranes and skin turgor. Dry membranes and inelastic skin indicate inadequate fluid volume and the need for increase in fluid intake (PO or IV route).

7. Measure and evaluate vital signs, CVP, and PAP (when available) every 1 to 4 hours, depending on hemodynamic stability. Be alert to increasing HR, decreasing CVP, and decreasing PAP, which indicate inadequate intravascular volume. Encourage increased oral intake (if possible), or consult with physician regarding increase in IV fluid intake.

8. Control sources of insensible fluid loss by humidifying oxygen, maintaining comfortable environment, and controlling fever (if present) with antipyretics such as acetaminophen.

9. Monitor for manifestations of electrolyte imbalance, most commonly hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia that are lost through fistula output.