Chapter 6 Gastrointestinal disease

Introduction

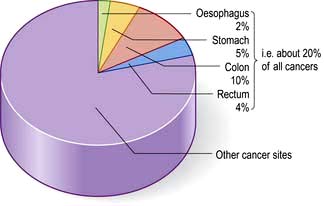

In developed countries gastrointestinal symptoms are a common reason for attendance to primary care clinics and to hospital outpatients. Approximately 75% of these consultations are for non-organic symptoms. The clinician’s main task is therefore to recognize when organic disease must be sought or excluded, remembering that 20% of all cancers occur in the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 6.1). In developing countries, malnutrition and poor hygiene make infection a more probable diagnosis. The clinician needs to recognize and treat these infections promptly and also help with prevention by encouraging good hygiene.

Gastrointestinal symptoms and signs

Dyspepsia and indigestion

Features of dyspepsia suggestive of serious diseases such as cancer are known as ‘Alarm’ symptoms.

Vomiting

Many gastrointestinal (and non-gastrointestinal) conditions are associated with vomiting (Table 6.1). This is controlled by a complex reflex involving central neural control centres located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla which are stimulated by the chemoreceptor trigger zones (CTZs) in the floor of the fourth ventricle, and also by vagal afferents from the gut. The central zones are directly stimulated by toxins, drugs, motion sickness and metabolic disturbances. Raised intracranial pressure has a direct effect on the vomiting centre leading to vomiting. Luminal toxins, inflammation and mechanical obstruction are local GI causes of vomiting.

Faeculent vomit suggests low intestinal obstruction or the presence of a gastrocolic fistula.

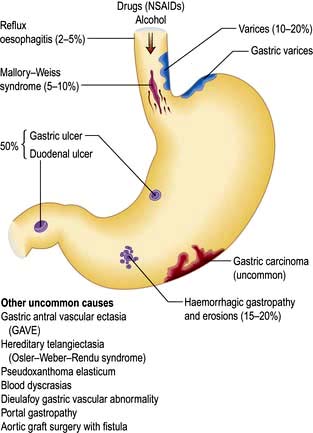

Haematemesis is vomiting fresh or altered blood (‘coffee-grounds’) (see p. 254).

Persistent nausea alone is often stress-related and is not due to gastrointestinal disease.

Flatulence

This term describes excessive wind. It is used to indicate belching, abdominal distension, gurgling and the passage of flatus per rectum. Swallowing air (aerophagia) is described on page 296. Some of the swallowed air passes into the intestine where most of it is absorbed, but some remains to be passed rectally. Colonic bacterial breakdown of non-absorbed carbohydrate also produces gas. Rectal flatus thus consists of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, hydrogen and methane. It is normal to pass rectal flatus up to 20 times/day. Causes of increased gas production and intake include high-fibre diet and carbonated drinks.

Diarrhoea and constipation

These are common complaints and in the community are not usually due to serious disease. They are described in detail on pages 291 and 282, respectively. Some general rules concerning the aetiology and investigation of diarrhoea are shown in Box 6.1.

![]() Box 6.1

Box 6.1

Simple rules in diarrhoea

Abdominal pain

Pain is stimulated mainly by the stretching of smooth muscle or organ capsules. Severe acute abdominal pain can be due to a large number of gastrointestinal conditions, and normally presents as an emergency (see p. 298). An apparent ‘acute abdomen’ can occasionally be due to referred pain from the chest, as in pneumonia or to metabolic causes, such as diabetic ketoacidosis or porphyria.

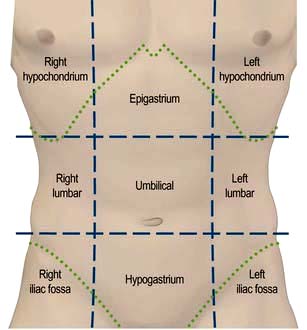

Site (Fig. 6.2), intensity, character, duration and frequency of the pain

Site (Fig. 6.2), intensity, character, duration and frequency of the pain

Aggravating and relieving factors

Aggravating and relieving factors

Associated symptoms, including non-gastrointestinal symptoms.

Associated symptoms, including non-gastrointestinal symptoms.

Upper abdominal pain

Right hypochondrial pain may originate from the gall bladder or biliary tract. Biliary pain can also be epigastric. Biliary pain is typically intermittent and severe, lasts a few hours and remits spontaneously to recur weeks or months later. Hepatic congestion (e.g. in hepatitis or cardiac failure) and sometimes peptic ulcer disease can present with pain in the right hypochondrium. Chronic, persistent or constant pain in the right (or left) hypochondrium in a well-looking patient is a frequent functional symptom; this chronic pain is not due to gall bladder disease (see p. 353).

Examination of the abdomen

Palpation

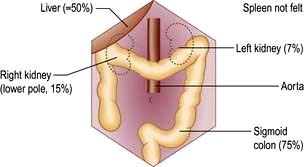

Look for palpable masses or abdominal tenderness. All abdominal quadrants should be palpated in turn followed by deeper palpations; remember to watch the patient’s face for signs of pain or discomfort. Evaluate any palpable mass and note its size, shape and consistency and whether it moves with respiration, to decide which organ is involved. Some abdominal organs may be just palpable normally, usually in thin people (Fig. 6.3). Reidel’s lobe is an anatomical variant consisting of a palpable enlargement of the lateral portion of the right lobe of the liver. The hernial orifices should be examined if intestinal obstruction is suspected.

Examination of the rectum and sigmoid colon

Proctoscopy (see Practical Box 6.1) is performed in all patients with a history of bright red rectal bleeding to look for anorectal pathology such as haemorrhoids; a rigid sigmoidoscope is too narrow and long to enable adequate examination of the anal canal.

Proctoscopy (see Practical Box 6.1) is performed in all patients with a history of bright red rectal bleeding to look for anorectal pathology such as haemorrhoids; a rigid sigmoidoscope is too narrow and long to enable adequate examination of the anal canal.

Sigmoidoscopy is part of the routine hospital examination in cases of diarrhoea and in patients with lower abdominal symptoms such as a change in bowel habit or rectal bleeding. The rigid sigmoidoscope allows inspection of a maximum of 20–25 cm of distal colon.

Sigmoidoscopy is part of the routine hospital examination in cases of diarrhoea and in patients with lower abdominal symptoms such as a change in bowel habit or rectal bleeding. The rigid sigmoidoscope allows inspection of a maximum of 20–25 cm of distal colon.

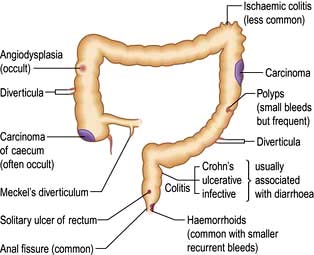

Flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) (60 cm) can reach up to the splenic flexure, and can be performed in the outpatient department or endoscopy unit after evacuation of the distal colon using an enema or suppository. FS can be used in patients with increased stool frequency or looseness or rectal bleeding to diagnose colitis or polyps. Most rectal bleeding is due to benign anorectal disease (haemorrhoids or fissure-in-ano) and an otherwise normal FS can be reassuring to avoid over-investigation. Up to 60% of colonic neoplasms occur within the range of FS (see Fig. 6.45) and it has therefore been proposed as screening test for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic individuals.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) (60 cm) can reach up to the splenic flexure, and can be performed in the outpatient department or endoscopy unit after evacuation of the distal colon using an enema or suppository. FS can be used in patients with increased stool frequency or looseness or rectal bleeding to diagnose colitis or polyps. Most rectal bleeding is due to benign anorectal disease (haemorrhoids or fissure-in-ano) and an otherwise normal FS can be reassuring to avoid over-investigation. Up to 60% of colonic neoplasms occur within the range of FS (see Fig. 6.45) and it has therefore been proposed as screening test for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic individuals.

![]() Practical Box 6.1

Practical Box 6.1

Sigmoidoscopy and proctoscopy

Sigmoidoscopy

The technique using a 25 cm rigid sigmoidoscope is easy to learn, provides valuable information and is safe in competent hands.

The technique using a 25 cm rigid sigmoidoscope is easy to learn, provides valuable information and is safe in competent hands.

No bowel preparation is required.

No bowel preparation is required.

Explain to the patient the nature of the procedure and obtain consent.

Explain to the patient the nature of the procedure and obtain consent.

The technique is relatively painless. In the irritable bowel syndrome, the patient’s pain is often reproduced by air insufflation:

The technique is relatively painless. In the irritable bowel syndrome, the patient’s pain is often reproduced by air insufflation:

Proctoscopy

1. The proctoscope is passed into the anus and the obturator is removed.

2. The patient strains down as the proctoscope is removed.

3. Haemorrhoids are seen as purplish veins in the left lateral, right posterior or right anterior positions.

4. Fissures may also be seen, but pain often prevents the procedure from being performed.

Stool examination

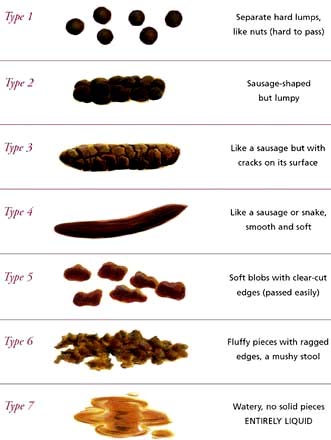

It is useful to confirm a patient’s account (e.g. passing of blood or steatorrhoea). The shape and size may be helpful (e.g. ‘rabbit dropping’ or ribbon-like stools in the irritable bowel syndrome). Stool charts for recording consistency and frequency of defecation are useful in inpatients to follow the progress of diarrhoea, particularly in the management of severe colitis. The Bristol Stool Chart is commonly used in the UK (Fig. 6.4).

Investigations

Routine haematology and biochemistry, followed by endoscopy and radiology, are the principal investigations. The investigation of small bowel disease is discussed in more detail on page 267. Manometry is mainly used in oesophageal disease (see p. 237) and anorectal disorders (see p. 286).

Endoscopy

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD, ‘gastroscopy’) is the investigation of choice for upper GI disorders with the possibility of therapy and mucosal biopsy. Findings include reflux oesophagitis, gastritis, ulcers and cancer. Therapeutic OGD is used to treat upper GI haemorrhage and both benign and malignant obstruction. Relative contraindications include severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a recent myocardial infarction, or severe instability of the atlantoaxial joints. The mortality for diagnostic endoscopy is 0.001% with significant complications in 1 : 10 000, usually when performed as an emergency (e.g. GI haemorrhage).

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD, ‘gastroscopy’) is the investigation of choice for upper GI disorders with the possibility of therapy and mucosal biopsy. Findings include reflux oesophagitis, gastritis, ulcers and cancer. Therapeutic OGD is used to treat upper GI haemorrhage and both benign and malignant obstruction. Relative contraindications include severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a recent myocardial infarction, or severe instability of the atlantoaxial joints. The mortality for diagnostic endoscopy is 0.001% with significant complications in 1 : 10 000, usually when performed as an emergency (e.g. GI haemorrhage).

Colonoscopy allows good visualization of the whole colon and terminal ileum. Biopsies can be obtained and polyps removed. Benign strictures can be dilated and malignant strictures stented. The success rate for reaching the caecum should be at least 90% after training. Cancer, polyps and diverticular disease are the commonest significant findings. Perforation occurs in 1 : 1000 examinations but this is higher (up to 2%) after polypectomy (see Practical Box 6.2).

Colonoscopy allows good visualization of the whole colon and terminal ileum. Biopsies can be obtained and polyps removed. Benign strictures can be dilated and malignant strictures stented. The success rate for reaching the caecum should be at least 90% after training. Cancer, polyps and diverticular disease are the commonest significant findings. Perforation occurs in 1 : 1000 examinations but this is higher (up to 2%) after polypectomy (see Practical Box 6.2).

Balloon enteroscopy, either double or single balloon, can examine the small bowel from the duodenum to the ileum using specialized enteroscopes in expert centres.

Balloon enteroscopy, either double or single balloon, can examine the small bowel from the duodenum to the ileum using specialized enteroscopes in expert centres.

Capsule endoscopy is used for the evaluation of obscure GI bleeding (after negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy) and for the detection of small bowel tumours and occult inflammatory bowel disease. It should be avoided if strictures are suspected.

Capsule endoscopy is used for the evaluation of obscure GI bleeding (after negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy) and for the detection of small bowel tumours and occult inflammatory bowel disease. It should be avoided if strictures are suspected.

![]() Practical Box 6.2

Practical Box 6.2

Gastroscopy and colonoscopy

Gastroscopy

1. Patient should be fasted for at least 4 hours.

2. Give oxygen and monitor oxygen saturation with an oximeter.

3. Give lidocaine throat spray or sedation (midazolam ± opiate if required).

4. Pass the gastroscope to the duodenum under direct vision.

5. Examine during insertion and withdrawal.

6. Gastroscopy takes 5–15 min, depending on the indication and findings.

7. Withhold fluid and food until LA/sedation wears off.

8. Complications are rare: beware of over-sedation, perforation and aspiration.

Colonoscopy

1. Stop oral iron a week before the procedure.

2. Restrict diet to low residue foods for 48 hours; clear fluids only for 24 hours.

3. Use local bowel cleansing regime, usually starting 24 hours beforehand (e.g. two sachets of sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate and 2–4 bisacodyl tablets, or macrogols 2–4 L, or local alternative; more if constipated).

4. Give oxygen and monitor O2 levels.

5. Give sedation (midazolam ± opiate) if required by patient.

6. Pass the colonoscope to the caecum or ileum under direct vision.

7. Examine in detail during withdrawal.

8. Colonoscopy takes 15–30 min, depending on the colon anatomy, indication and findings.

9. Withhold fluid and food until sedation wears off.

10. Observe patient for at least an hour after sedation given.

11. Complications are rare: beware of over-sedation, perforation and aspiration.

Imaging

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is performed with a gastroscope incorporating an ultrasound probe at the tip. It is used diagnostically for lesions in the oesophageal or gastric wall, including the detailed TNM staging (see p. 245) of oesophageal/gastric cancer and for the detection and biopsy of pancreatic tumours and cysts.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is performed with a gastroscope incorporating an ultrasound probe at the tip. It is used diagnostically for lesions in the oesophageal or gastric wall, including the detailed TNM staging (see p. 245) of oesophageal/gastric cancer and for the detection and biopsy of pancreatic tumours and cysts.

Endoanal and endorectal ultrasonography are performed to define the anatomy of the anal sphincters (see p. 285), to detect perianal disease and to stage superficial rectal tumours.

Endoanal and endorectal ultrasonography are performed to define the anatomy of the anal sphincters (see p. 285), to detect perianal disease and to stage superficial rectal tumours.

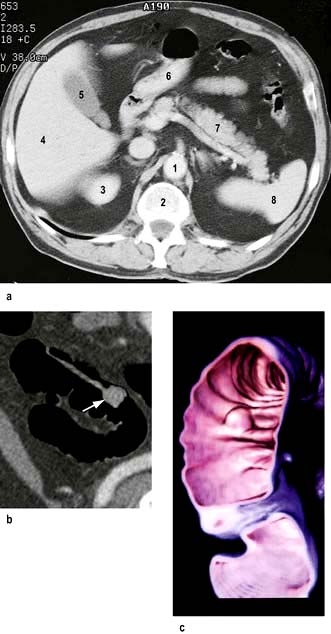

Computed tomography involves a significant dose of radiation (approximately 10 millisieverts). Modern multislice fast scanners and techniques involving intraluminal and intravenous contrast enhance diagnostic capability. Intraluminal contrast may be positive (Gastrografin or Omnipaque) or negative (usually water). The bowel wall and mesentery are well seen after intravenous contrast especially with negative intraluminal contrast. Clinically unsuspected diseases of other abdominal organs are quite often also revealed (Fig. 6.5a).

CT is widely used as a first-line investigation for the acute abdomen. CT is sensitive for small volumes of gas from a perforated viscus as well as leakage of contrast from the gut lumen.

CT is widely used as a first-line investigation for the acute abdomen. CT is sensitive for small volumes of gas from a perforated viscus as well as leakage of contrast from the gut lumen.

Inflammatory conditions such as abscesses, appendicitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease and its complications are well demonstrated. In high-grade bowel obstruction, CT is usually diagnostic of both the presence and the cause of the obstruction.

Inflammatory conditions such as abscesses, appendicitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease and its complications are well demonstrated. In high-grade bowel obstruction, CT is usually diagnostic of both the presence and the cause of the obstruction.

CT is widely used in cancer staging and as guidance for biopsy of tumour or lymph nodes.

CT is widely used in cancer staging and as guidance for biopsy of tumour or lymph nodes.

CT pneumocolon/CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) after CO2 insufflation into a previously cleansed colon provides an alternative to colonoscopy for diagnosis of colon mass lesions (Fig. 6.5b). It is being evaluated as a screening test for colon pathology with sensitivities of over 90% for >10 mm polyps.

CT pneumocolon/CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) after CO2 insufflation into a previously cleansed colon provides an alternative to colonoscopy for diagnosis of colon mass lesions (Fig. 6.5b). It is being evaluated as a screening test for colon pathology with sensitivities of over 90% for >10 mm polyps.

Unprepared CT is a good test for colon cancer in the frail (often elderly) patient who would have problems with bowel preparation.

Unprepared CT is a good test for colon cancer in the frail (often elderly) patient who would have problems with bowel preparation.

Contrast studies

Barium swallow examines the oesophagus and proximal stomach. Its main use is for investigating dysphagia.

Barium swallow examines the oesophagus and proximal stomach. Its main use is for investigating dysphagia.

Double-contrast barium meal examines the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. Barium is given to produce mucosal coating and effervescent granules producing carbon dioxide in the stomach create a double contrast between gas and barium. This test has a high accuracy for the detection of significant pathology – ulcers and cancer – but requires good technique. Gastroscopy is a more sensitive test and enables biopsy of suspicious areas.

Double-contrast barium meal examines the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. Barium is given to produce mucosal coating and effervescent granules producing carbon dioxide in the stomach create a double contrast between gas and barium. This test has a high accuracy for the detection of significant pathology – ulcers and cancer – but requires good technique. Gastroscopy is a more sensitive test and enables biopsy of suspicious areas.

Small bowel meal or follow-through specifically examines the small bowel. Ingested barium passes through the small bowel into the right colon. The fold pattern and calibre of the small bowel are assessed. Specific views of the terminal ileum can be obtained and are used to identify early changes in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease.

Small bowel meal or follow-through specifically examines the small bowel. Ingested barium passes through the small bowel into the right colon. The fold pattern and calibre of the small bowel are assessed. Specific views of the terminal ileum can be obtained and are used to identify early changes in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease.

Small bowel enema (enteroclysis) is an alternative specific technique for small bowel examination. A tube is passed into the duodenum and a large volume of dilute barium is introduced. It is particularly used to demonstrate strictures or adhesions when there is suspicion of intermittent obstruction. Generally, this has been replaced by MR enteroclysis.

Small bowel enema (enteroclysis) is an alternative specific technique for small bowel examination. A tube is passed into the duodenum and a large volume of dilute barium is introduced. It is particularly used to demonstrate strictures or adhesions when there is suspicion of intermittent obstruction. Generally, this has been replaced by MR enteroclysis.

Barium enema examines the colon and is used for altered bowel habit. Colonoscopy and CT colonography have largely replaced this examination for rectal bleeding, polyps and inflammatory bowel disease.

Barium enema examines the colon and is used for altered bowel habit. Colonoscopy and CT colonography have largely replaced this examination for rectal bleeding, polyps and inflammatory bowel disease.

Absorbable water-soluble (Gastrografin or Omnipaque) contrast agents should be used in preference to barium when perforation is suspected anywhere in the gut.

Absorbable water-soluble (Gastrografin or Omnipaque) contrast agents should be used in preference to barium when perforation is suspected anywhere in the gut.

Radioisotopes

Detect urease activity of Helicobacter pylori – 13C urea breath test (see p. 249)

Detect urease activity of Helicobacter pylori – 13C urea breath test (see p. 249)

Assess oesophageal reflux – gamma camera scan after oral [99mTc]technetium-sulphur colloid

Assess oesophageal reflux – gamma camera scan after oral [99mTc]technetium-sulphur colloid

Measure rate of gastric emptying – sequential gamma camera scans after oral [99mTc]technetium-sulphur colloid or 111In-DTPA (indium-labelled diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid)

Measure rate of gastric emptying – sequential gamma camera scans after oral [99mTc]technetium-sulphur colloid or 111In-DTPA (indium-labelled diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid)

Demonstrate a Meckel’s diverticulum – gamma camera scan after i.v. [99mTc]pertechnetate, which has affinity for gastric mucosa

Demonstrate a Meckel’s diverticulum – gamma camera scan after i.v. [99mTc]pertechnetate, which has affinity for gastric mucosa

Assess extent of inflammation and presence of inflammatory collections in inflammatory bowel disease – gamma camera scan after i.v. 99mTc-HMPAO (hexamethylpropylene amine oxime) labelled white cells

Assess extent of inflammation and presence of inflammatory collections in inflammatory bowel disease – gamma camera scan after i.v. 99mTc-HMPAO (hexamethylpropylene amine oxime) labelled white cells

Evaluate neuroendocrine tumours and their metastases – gamma camera scan after i.v. radiolabelled octreotide or MIBG (meta-iodobenzylguanidine)

Evaluate neuroendocrine tumours and their metastases – gamma camera scan after i.v. radiolabelled octreotide or MIBG (meta-iodobenzylguanidine)

Assess obscure gastrointestinal bleeding – gamma camera abdominal scan after i.v. injection of red cells labelled with 99mTc (only useful if the bleeding is >2 mL/min)

Assess obscure gastrointestinal bleeding – gamma camera abdominal scan after i.v. injection of red cells labelled with 99mTc (only useful if the bleeding is >2 mL/min)

Measure albumin loss in the stools (in protein-losing enteropathy) – following albumin labelled in vivo with i.v. 51CrCl3. This test has been replaced by the measurement of the intestinal clearance of α1 antitrypsin

Measure albumin loss in the stools (in protein-losing enteropathy) – following albumin labelled in vivo with i.v. 51CrCl3. This test has been replaced by the measurement of the intestinal clearance of α1 antitrypsin

Assess bile salt malabsorption (in patients with unexplained diarrhoea) – gamma camera scan to measure both isotope retention and faecal loss of orally administered 75selenium-homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) (see p. 293)

Assess bile salt malabsorption (in patients with unexplained diarrhoea) – gamma camera scan to measure both isotope retention and faecal loss of orally administered 75selenium-homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) (see p. 293)

Detect bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel – measure 14CO2 in breath following oral 14C glycocholic acid.

Detect bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel – measure 14CO2 in breath following oral 14C glycocholic acid.

The mouth

Recurrent aphthous ulceration

Minor aphthous ulcers are the most common, are <10 mm diameter, have a grey/white centre with a thin erythematous halo and heal within 14 days without scarring. They rarely affect the dorsum of the tongue or hard palate.

Minor aphthous ulcers are the most common, are <10 mm diameter, have a grey/white centre with a thin erythematous halo and heal within 14 days without scarring. They rarely affect the dorsum of the tongue or hard palate.

Major aphthous ulcers (>10 mm diameter) often persist for weeks or months and heal with scarring.

Major aphthous ulcers (>10 mm diameter) often persist for weeks or months and heal with scarring.

The tongue

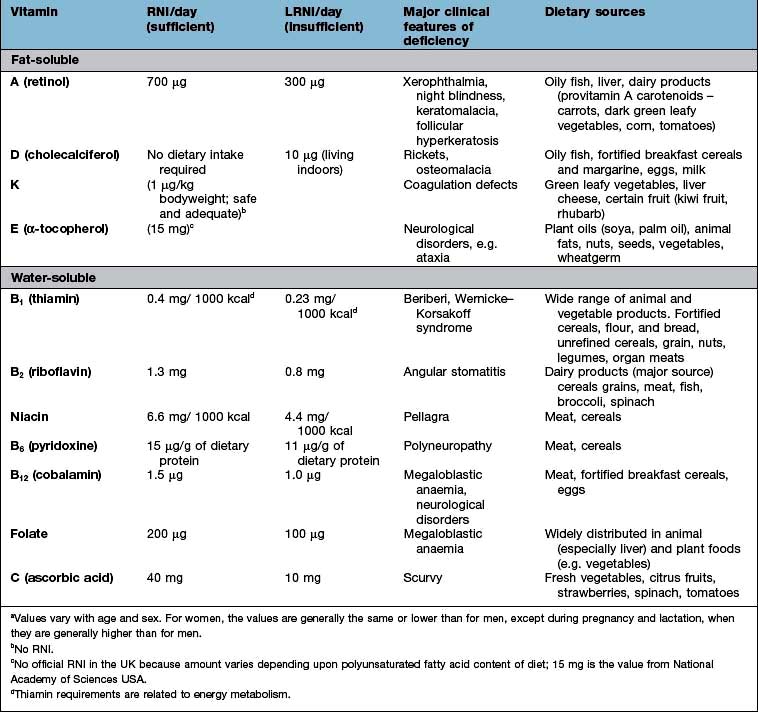

Glossitis is a red, smooth, sore tongue associated with B12, folate or iron deficiency. It is also seen in infections due to Candida and in riboflavin and nicotinic acid deficiency.

Glossitis is a red, smooth, sore tongue associated with B12, folate or iron deficiency. It is also seen in infections due to Candida and in riboflavin and nicotinic acid deficiency.

A black hairy tongue is due to a proliferation of chromogenic microorganisms causing brown staining of elongated filiform papillae. The causes are unknown, but heavy smoking and the use of antiseptic mouthwashes have been implicated.

A black hairy tongue is due to a proliferation of chromogenic microorganisms causing brown staining of elongated filiform papillae. The causes are unknown, but heavy smoking and the use of antiseptic mouthwashes have been implicated.

A geographic tongue is an idiopathic condition occurring in 1–2% of the population and may be familial. There are erythematous areas surrounded by well-defined, slightly raised irregular margins. The lesions are usually painless and the patient should be reassured.

A geographic tongue is an idiopathic condition occurring in 1–2% of the population and may be familial. There are erythematous areas surrounded by well-defined, slightly raised irregular margins. The lesions are usually painless and the patient should be reassured.

The gums

Chronic gingivitis follows the accumulation of bacterial plaque. It resolves when the plaque is removed. It is the most common cause of bleeding gums.

Chronic gingivitis follows the accumulation of bacterial plaque. It resolves when the plaque is removed. It is the most common cause of bleeding gums.

Acute (necrotizing) ulcerative gingivitis (‘Vincent’s angina’) is characterized by the proliferation of spirochaete and fusiform bacteria associated with poor oral hygiene and smoking. Treatment is with oral metronidazole 200 mg three times daily for 3 days, improved oral hygiene and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash.

Acute (necrotizing) ulcerative gingivitis (‘Vincent’s angina’) is characterized by the proliferation of spirochaete and fusiform bacteria associated with poor oral hygiene and smoking. Treatment is with oral metronidazole 200 mg three times daily for 3 days, improved oral hygiene and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash.

Desquamative gingivitis is a clinical description of smooth, red atrophic gingivae caused by lichen planus or mucous membrane pemphigoid. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Desquamative gingivitis is a clinical description of smooth, red atrophic gingivae caused by lichen planus or mucous membrane pemphigoid. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Gingival swelling may be due to inflammation or fibrous hyperplasia. The latter may be hereditary (gingival fibromatosis) or associated with drugs (e.g. phenytoin, ciclosporin, nifedipine). Inflammatory swellings are seen in pregnancy, gingivitis and scurvy. Swelling due to infiltration is seen in acute leukaemia and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Gingival swelling may be due to inflammation or fibrous hyperplasia. The latter may be hereditary (gingival fibromatosis) or associated with drugs (e.g. phenytoin, ciclosporin, nifedipine). Inflammatory swellings are seen in pregnancy, gingivitis and scurvy. Swelling due to infiltration is seen in acute leukaemia and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

The salivary glands

Dry mouth (xerostomia) can result from a variety of causes:

Drugs (e.g. antimuscarinic, antiparkinsonian, antihistamines, lithium, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic and related antidepressants, and clonidine)

Drugs (e.g. antimuscarinic, antiparkinsonian, antihistamines, lithium, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic and related antidepressants, and clonidine)

Sialadenitis

Acute sialadenitis is viral (mumps, p. 110) or bacterial. Bacterial sialadenitis is a painful ascending infection with Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes and Strep. pneumoniae, usually secondary to secretory failure. Pus can be expressed from the affected duct.

The pharynx and oesophagus

Structure and physiology

Swallowing

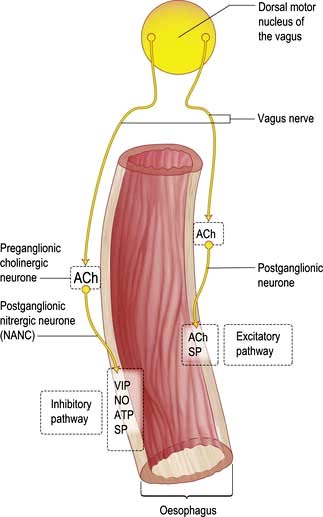

The smooth muscle of the thoracic oesophagus and lower oesophageal sphincter is supplied by vagal autonomic motor nerves consisting of extrinsic preganglionic fibres and intramural postganglionic neurones in the myenteric plexus (Fig. 6.6). There are parallel excitatory and inhibitory pathways.

Symptoms of oesophageal disorders

Major oesophageal symptoms are:

Dysphagia, or difficulty in swallowing, is defined as a sensation of obstruction during the passage of liquid or solid through the pharynx or oesophagus, i.e. within 15 s of food leaving the mouth. The characteristics of the progression of dysphagia to solids can be helpful, e.g. intermittent slow progression with a history of heartburn suggests a benign peptic stricture; relentless progression over a few weeks suggests a malignant stricture. The slow onset of dysphagia for solids and liquids at the same time suggests a motility disorder, e.g. achalasia (see p. 237). The causes are shown in Table 6.3.

Dysphagia, or difficulty in swallowing, is defined as a sensation of obstruction during the passage of liquid or solid through the pharynx or oesophagus, i.e. within 15 s of food leaving the mouth. The characteristics of the progression of dysphagia to solids can be helpful, e.g. intermittent slow progression with a history of heartburn suggests a benign peptic stricture; relentless progression over a few weeks suggests a malignant stricture. The slow onset of dysphagia for solids and liquids at the same time suggests a motility disorder, e.g. achalasia (see p. 237). The causes are shown in Table 6.3.

Odynophagia is pain during the act of swallowing and is suggestive of oesophagitis. Causes include reflux, infection, chemical oesophagitis due to drugs such as bisphosphonates or slow-release potassium or associated with oesophageal stenosis.

Odynophagia is pain during the act of swallowing and is suggestive of oesophagitis. Causes include reflux, infection, chemical oesophagitis due to drugs such as bisphosphonates or slow-release potassium or associated with oesophageal stenosis.

Substernal discomfort, heartburn. This is a common symptom of reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus. It is usually a retrosternal burning pain that can spread to the neck, across the chest, and when severe can be difficult to distinguish from the pain of ischaemic heart disease. It is often worst lying down at night when gravity promotes reflux or on bending or stooping.

Substernal discomfort, heartburn. This is a common symptom of reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus. It is usually a retrosternal burning pain that can spread to the neck, across the chest, and when severe can be difficult to distinguish from the pain of ischaemic heart disease. It is often worst lying down at night when gravity promotes reflux or on bending or stooping.

Regurgitation is the effortless reflux of oesophageal contents into the mouth and pharynx. Uncommon in normal subjects, it occurs frequently in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or organic stenosis.

Regurgitation is the effortless reflux of oesophageal contents into the mouth and pharynx. Uncommon in normal subjects, it occurs frequently in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or organic stenosis.

Investigations available for oesophageal disorders

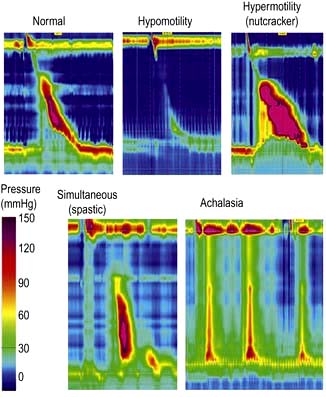

Manometry (Fig. 6.7) is performed by passing a catheter through the nose into the oesophagus and measuring the pressures generated within the oesophagus. It is used to assess oesophageal motor activity. It is not a primary investigation and should be performed only when the diagnosis has not been achieved by history, barium radiology or endoscopy. Recordings are usually made over a short time period, or much more rarely for up to 24 h. High resolution manometry has superseded conventional manometry and the greater concentration of pressure sensors enables the identification of a wider range of abnormalities of oesophageal function with a greater diagnostic accuracy.

Manometry (Fig. 6.7) is performed by passing a catheter through the nose into the oesophagus and measuring the pressures generated within the oesophagus. It is used to assess oesophageal motor activity. It is not a primary investigation and should be performed only when the diagnosis has not been achieved by history, barium radiology or endoscopy. Recordings are usually made over a short time period, or much more rarely for up to 24 h. High resolution manometry has superseded conventional manometry and the greater concentration of pressure sensors enables the identification of a wider range of abnormalities of oesophageal function with a greater diagnostic accuracy.

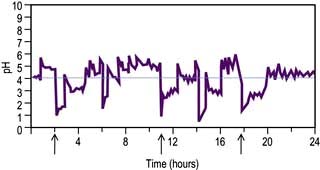

pH monitoring – 24-hour ambulatory monitoring uses a pH-sensitive probe positioned in the lower oesophagus and is used to identify acid reflux episodes (pH <4). Catheter and implantable sensors are available; both are insensitive to alkali. Although only 5–10% of recorded acid reflux episodes are perceived by the patient, pH is a valuable means of correlating episodes of acid reflux with patient’s symptoms.

pH monitoring – 24-hour ambulatory monitoring uses a pH-sensitive probe positioned in the lower oesophagus and is used to identify acid reflux episodes (pH <4). Catheter and implantable sensors are available; both are insensitive to alkali. Although only 5–10% of recorded acid reflux episodes are perceived by the patient, pH is a valuable means of correlating episodes of acid reflux with patient’s symptoms.

Impedance uses a catheter to measure the resistance to flow of ‘alternating current’ in the contents of the oesophagus. Combined with pH it allows assessment of acid, weakly acid, alkaline and gaseous reflux, which is helpful in understanding the symptoms that are produced by a non-acid reflux. Treatment is, however, still difficult in these conditions.

Impedance uses a catheter to measure the resistance to flow of ‘alternating current’ in the contents of the oesophagus. Combined with pH it allows assessment of acid, weakly acid, alkaline and gaseous reflux, which is helpful in understanding the symptoms that are produced by a non-acid reflux. Treatment is, however, still difficult in these conditions.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

Pathophysiology

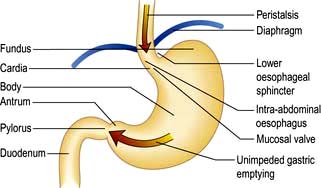

Between swallows, the muscles of the oesophagus are relaxed except for those of the sphincters. The LOS remains closed due to the unique property of the muscle and relaxes when swallowing is initiated. Transient Lower Oesophageal Sphincter Relaxations (TLESRs) are part of normal physiology, but occur more frequently in GORD patients (Fig. 6.8).

Small amounts of gastro-oesophageal reflux are normal. The lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) in the distal oesophagus is in a state of tonic contraction and relaxes transiently to allow the passage of a food bolus (see p. 229). Sphincter pressure also increases in response to rises in intra-abdominal and intragastric pressures.

Oesophageal mucosal defence mechanisms

Surface. Mucus and the unstirred water layer trap bicarbonate. This mechanism is a weak buffering mechanism compared to that in the stomach and duodenum.

Surface. Mucus and the unstirred water layer trap bicarbonate. This mechanism is a weak buffering mechanism compared to that in the stomach and duodenum.

Epithelium. The apical cell membranes and the junctional complexes between cells act to limit diffusion of H+ into the cells. In oesophagitis, the junctional complexes are damaged leading to increased H+ diffusion and cellular damage.

Epithelium. The apical cell membranes and the junctional complexes between cells act to limit diffusion of H+ into the cells. In oesophagitis, the junctional complexes are damaged leading to increased H+ diffusion and cellular damage.

Postepithelium. Bicarbonate normally buffers acid in the cells and intracellular spaces. Hydrogen ions impair the growth and replication of damaged cells.

Postepithelium. Bicarbonate normally buffers acid in the cells and intracellular spaces. Hydrogen ions impair the growth and replication of damaged cells.

Sensory mechanisms. Acid stimulates primary sensory neurones in the oesophagus by activating the vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1). This can initiate inflammation and release of pro-inflammatory substances from the tissue and produce pain. Pain can also be due to contraction of longitudinal oesophageal muscle.

Sensory mechanisms. Acid stimulates primary sensory neurones in the oesophagus by activating the vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1). This can initiate inflammation and release of pro-inflammatory substances from the tissue and produce pain. Pain can also be due to contraction of longitudinal oesophageal muscle.

Clinical features

Heartburn is the major feature. Factors associated with GORD are shown in Table 6.4.

The correlation between heartburn and oesophagitis is poor. Some patients have mild oesophagitis but severe heartburn; others have severe oesophagitis without symptoms, and may present with a haematemesis or iron deficiency anaemia from chronic blood loss. Psychosocial factors are often determinants of symptom severity. Many patients erroneously ascribe their symptoms to their hiatus hernia (Box 6.2) but the symptoms are due to reflux.

Differentiation of cardiac and oesophageal pain can be difficult; 20% of cases admitted to a coronary care unit have GORD (Box 6.3). In addition to the clinical features, a trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is always worthwhile and if symptoms persist, ambulatory pH and impedance monitoring should be performed.

Diagnosis and investigations

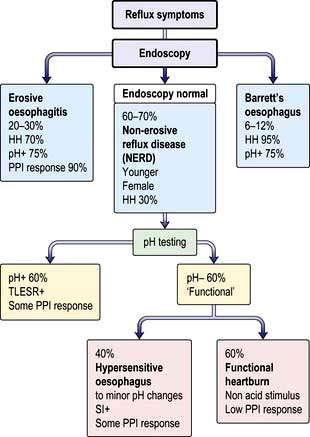

The clinical diagnosis can usually be made without investigation. Unless there are alarm signs, especially dysphagia (see p. 229), patients under the age of 45 years can safely be treated initially without investigations. If investigation is required, there are two aims:

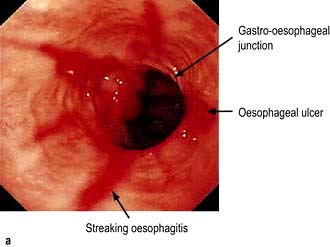

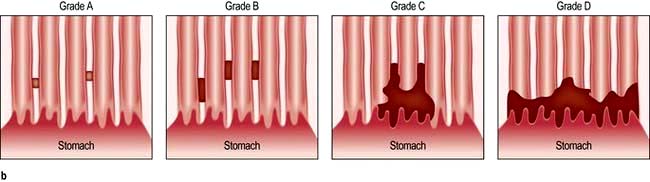

Assess oesophagitis and hiatal hernia by endoscopy. If there is oesophagitis (Fig. 6.9) or Barrett’s oesophagus (see p. 241), reflux is confirmed.

Assess oesophagitis and hiatal hernia by endoscopy. If there is oesophagitis (Fig. 6.9) or Barrett’s oesophagus (see p. 241), reflux is confirmed.

Document reflux by intraluminal monitoring (Fig. 6.10). 24-hour intraluminal pH monitoring or impedance combined with manometry is helpful if there is no response to PPI and should always be performed to confirm reflux before surgery. Excessive reflux is defined as a pH <4 for >4% of the time. There should also be a good correlation between reflux (pH <4.0) and symptoms. It is also helpful to assess oesophageal dysmotility as a potential cause of the symptoms.

Document reflux by intraluminal monitoring (Fig. 6.10). 24-hour intraluminal pH monitoring or impedance combined with manometry is helpful if there is no response to PPI and should always be performed to confirm reflux before surgery. Excessive reflux is defined as a pH <4 for >4% of the time. There should also be a good correlation between reflux (pH <4.0) and symptoms. It is also helpful to assess oesophageal dysmotility as a potential cause of the symptoms.

Treatment

Drugs

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs: omeprazole, rabeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole) inhibit gastric hydrogen/potassium-ATPase. PPIs reduce gastric acid secretion by up to 90% and are the drugs of choice for all but mild cases. Most patients with GORD will respond well, but this is only 20–30% of patients presenting with heartburn. Patients with severe symptoms may need twice-daily PPIs and prolonged treatment, often for years. Once oesophageal sensitivity has normalized, a lower dose, e.g. omeprazole 10 mg, may be sufficient for maintenance. The patients who do not respond to a PPI are sometimes described as having non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) (Fig. 6.11), when the endoscopy is normal. These patients are usually female and often the symptoms are functional, although a small group have a hypersensitive oesophagus, giving discomfort with only slight changes in pH. Isomers of some of the original PPIs (e.g. dexlansoprazole) have the benefit of more effective gastric acid inhibition over a longer time period as their metabolism to the active metabolite is slower.

Complications

Barrett’s oesophagus

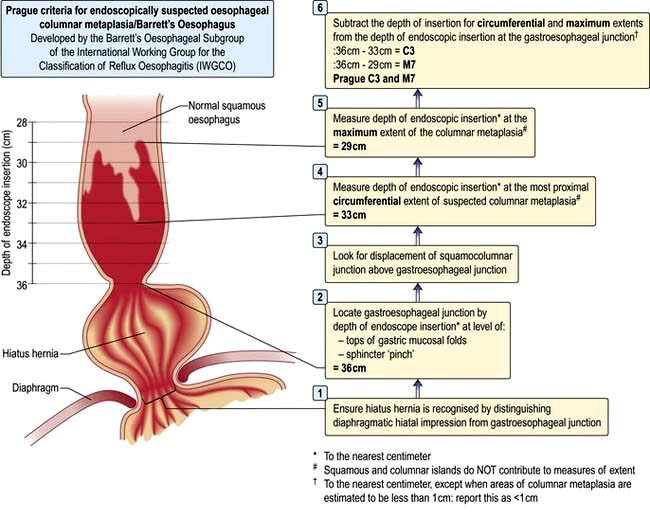

Diagnosis and classification. The diagnosis is made by endoscopy showing proximal displacement of the squamocolumnar mucosal junction and biopsies demonstrating columnar lining above the proximal gastric folds; intestinal metaplasia is no longer a requirement of the British Society of Gastroenterology definition, but is central to the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines. Barrett’s oesophagus may be seen as a continual circumferential sheet, or finger-like projections extending upwards from the squamocolumnar junction or as islands of columnar mucosa interspersed in areas of residual squamous mucosa. The Prague Classification (Fig. 6.12) is used for recording the endoscopic distribution, stating both the length of circumferential CLO (C measurement) as well as the maximum length (M measurement), the distance from the top of the gastric folds to the most proximal tongue of the columnar mucosa.

Figure 6.12 The Prague Criteria for endoscopically suspected oesophageal columnar metaplasia/Barrett’s oesophagus.

FURTHER READING

Galmiche J-P, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S et al., for the LOTUS Trial Collaborators. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: The LOTUS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2011; 305:1969–1977.

Kahrilas PJ. Clinical practice. Gastrooesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1700–1707.

Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF; American Gastroenterological Association Institute; Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:1392–1413.

Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P. GERD in 2010: diagnosis, novel mechanisms of disease and promising agents. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 8:73–74.

Massey BT. Physiology of oral cavity, pharynx and upper esophageal sphincter. In: Goyal R, Shaker R (eds). GI Motility. Also online: www.nature.com/gimo/contents/pt1/full/gimo2.html

Motility disorders

Achalasia

Pathogenesis

The aetiology is unknown. Autoimmune, neurodegenerative and viral aetiologies have been implicated. A similar clinical picture is seen in chronic Chagas’ disease (American try-panosomiasis, p. 148) where there is damage to the neural plexus of the gut.

Investigations

Chest X-ray shows a dilated oesophagus, sometimes with a fluid level seen behind the heart. The fundal gas shadow is absent.

Chest X-ray shows a dilated oesophagus, sometimes with a fluid level seen behind the heart. The fundal gas shadow is absent.

Barium swallow shows lack of peristalsis and often synchronous contractions in the body of the oesophagus, sometimes with dilatation. The lower end shows a ‘bird’s beak’ due to failure of the sphincter to relax (Fig. 6.13).

Barium swallow shows lack of peristalsis and often synchronous contractions in the body of the oesophagus, sometimes with dilatation. The lower end shows a ‘bird’s beak’ due to failure of the sphincter to relax (Fig. 6.13).

Oesophagoscopy is performed to exclude a carcinoma at the lower end of the oesophagus, which can produce a similar X-ray appearance. When there is marked dilatation, a 24-hour liquid-only diet and a washout prior to endoscopy is useful to remove food debris. In true achalasia the endoscope passes through the lower oesophageal sphincter with little resistance.

Oesophagoscopy is performed to exclude a carcinoma at the lower end of the oesophagus, which can produce a similar X-ray appearance. When there is marked dilatation, a 24-hour liquid-only diet and a washout prior to endoscopy is useful to remove food debris. In true achalasia the endoscope passes through the lower oesophageal sphincter with little resistance.

CT scan excludes distal oesophageal cancer.

CT scan excludes distal oesophageal cancer.

Manometry shows aperistalsis of the oesophagus and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (Fig. 6.7).

Manometry shows aperistalsis of the oesophagus and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (Fig. 6.7).

Treatment

Reflux oesophagitis complicates all procedures and the aperistalsis of the oesophagus remains.

FURTHER READING

Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB et al., for the European Achalasia Trial Investigators. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1807–1816.

Richter JE, Boeckxstaens GE. Management of achalasia: surgery or pneumatic dilation. Gut 2011; 60:869–876.

Systemic sclerosis

The oesophagus is involved in almost all patients with this disease. Diminished peristalsis and oesophageal clearance, detected manometrically (Fig. 6.7) or by barium swallow, is due to replacement of the smooth muscle by fibrous tissue. LOS pressure is decreased, allowing reflux with consequent mucosal damage. Strictures may develop. Initially there are no symptoms, but dysphagia and heartburn occur as the oesophagus becomes more severely involved. Similar motility abnormalities may be found in other autoimmune rheumatic disorders, particularly if Raynaud’s phenomenon is present. Treatment is as for reflux (see p. 240) and benign stricture.

Diffuse oesophageal spasm

This is a severe form of oesophageal dysmotility that can sometimes produce retrosternal chest pain and dysphagia. It can accompany GORD. Swallowing is accompanied by bizarre and marked contractions of the oesophagus without normal peristalsis (Fig. 6.7). On barium swallow the appearance may be that of a ‘corkscrew’ oesophagus. However, asymptomatic oesophageal ‘dysmotility’ is not infrequent, particularly in patients over the age of 60 years.

Other oesophageal disorders

Oesophageal diverticulum

Immediately above the upper oesophageal sphincter (pharyngeal pouch – Zenker’s diverticulum) (see p. 1054).

Immediately above the upper oesophageal sphincter (pharyngeal pouch – Zenker’s diverticulum) (see p. 1054).

Near the middle of the oesophagus (traction diverticulum due to inflammation, or associated with diffuse oesophageal spasm or mediastinal fibrosis)

Near the middle of the oesophagus (traction diverticulum due to inflammation, or associated with diffuse oesophageal spasm or mediastinal fibrosis)

Just above the lower oesophageal sphincter (epiphrenic diverticulum – associated with achalasia).

Just above the lower oesophageal sphincter (epiphrenic diverticulum – associated with achalasia).

Usually detected incidentally on a barium swallow performed for other reasons, these are often asymptomatic. Dysphagia and regurgitation can occur with a pharyngeal pouch (see p. 1054).

Rings and webs

Lower oesophageal rings

Lower oesophageal rings are of two types:

1. Mucosal (Schatzki’s ring, also called B ring) located at the squamocolumnar mucosal junction; it is common, and is associated with characteristic history of intermittent bolus obstruction. Barium swallow with a distended oesophagus shows the abnormality which may be difficult to see at endoscopy.

2. Muscular (A ring) located proximal to the mucosal ring and uncommon. It is covered by squamous epithelium and may cause dysphagia.

Benign oesophageal stricture

Peptic stricture secondary to reflux is the most common cause of benign strictures (for treatment, see p. 241). They also occur after the ingestion of corrosives, after radiotherapy, after sclerosis of varices, and following prolonged nasogastric intubation. Dysphagia is usually treated by endoscopic dilatation. Surgery is sometimes required.

Oesophageal tumours

Cancer of the oesophagus

Epidemiology and aetiological factors

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

In the UK, the incidence is 5–10 per 100 000 and represents 2.2% of all malignant disease. The incidence of SCC is decreasing, in contrast to adenocarcinoma. SCC of the oesophagus is more common in men (2 : 1). Risk factors are shown in Table 6.5.

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma |

|---|---|

|

Tobacco smoking |

Longstanding, heartburn |

|

High alcohol intake |

Barrett’s oesophagus |

|

Plummer–Vinson syndrome |

Tobacco smoking |

|

Achalasia |

Obesity |

|

Corrosive stricturesCoeliac diseaseBreast cancer treated with radiotherapy |

Breast cancer treated with radiotherapy |

|

Older age |

|

|

|

|

|

Tylosisa |

|

a Tylosis is a rare autosomal dominant condition with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles.

Adenocarcinoma

These tumours primarily arise in columnar-lined epithelium in the lower oesophagus (see also Barrett’s oesophagus, p. 241). The incidence of this tumour is increasing in western industrialized countries). A study of the cancer registry in the USA estimated that incidence in white males rose four-fold from 1979 to 2004. Extension of an adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia into the oesophagus can present with the same symptoms. Previous reflux symptoms increase the risk up to eight-fold and the risk is proportional to their severity.

Investigation

Diagnostic

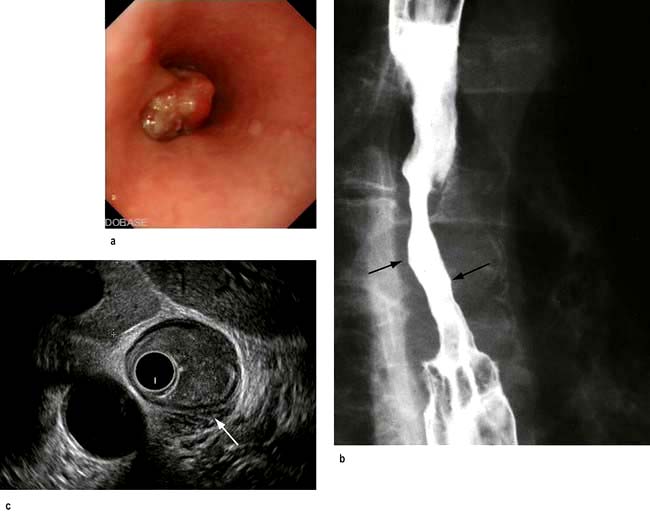

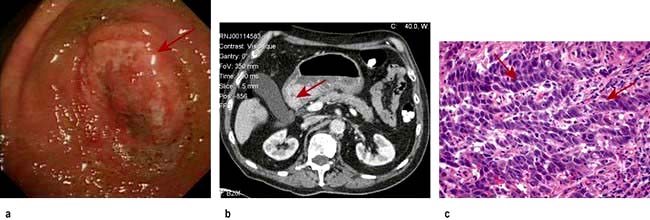

Endoscopy provides histological and or cytological proof of the carcinoma (Fig. 6.14a).

Endoscopy provides histological and or cytological proof of the carcinoma (Fig. 6.14a).

Barium swallow can be useful where the differential diagnosis of dysphagia includes a motility disorder such as achalasia (Fig. 6.14b).

Barium swallow can be useful where the differential diagnosis of dysphagia includes a motility disorder such as achalasia (Fig. 6.14b).

Staging

The TNM staging system is used (see p. 253), similar to the one used for gastric cancer. Tumour invasion of the wall of the oesophagus (T), presence of tumour in lymph nodes (N) or metastases (M) are combined into stage categories. Tumours arising in the cervical, thoracic and oesophagus, or abdominal oesophagus, including those that arise from within 5 cm from the gastro-oesophageal junction, share the same TNM staging criteria, but recent reclassification has differentiated between squamous and oesophageal cancers.

CT scan of the thorax and upper abdomen shows the volume of the tumour, local invasion, peritumoral and coeliac lymph node involvement and metastases in the lung and elsewhere.

CT scan of the thorax and upper abdomen shows the volume of the tumour, local invasion, peritumoral and coeliac lymph node involvement and metastases in the lung and elsewhere.

MRI is equivalent to CT in local staging but not as good for pulmonary metastases.

MRI is equivalent to CT in local staging but not as good for pulmonary metastases.

Endoscopic ultrasound has an accuracy rate of nearly 90% for assessing depth of tumour and infiltration and 80% for staging lymph node involvement. It is useful if CT does not show a lesion already too advanced for surgery. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of lymph nodes improves staging accuracy, particularly of the coeliac nodes. Accurate T staging is necessary as cancers confined to the superficial mucosa can be removed endoscopically (Fig. 6.14c).

Endoscopic ultrasound has an accuracy rate of nearly 90% for assessing depth of tumour and infiltration and 80% for staging lymph node involvement. It is useful if CT does not show a lesion already too advanced for surgery. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of lymph nodes improves staging accuracy, particularly of the coeliac nodes. Accurate T staging is necessary as cancers confined to the superficial mucosa can be removed endoscopically (Fig. 6.14c).

Laparoscopy is useful if the tumour is at the cardia, to look for peritoneal and node metastases.

Laparoscopy is useful if the tumour is at the cardia, to look for peritoneal and node metastases.

Positron emission tomography (PET) after fluorodeoxyglucose is used principally to confirm distant metastases suspected on CT.

Positron emission tomography (PET) after fluorodeoxyglucose is used principally to confirm distant metastases suspected on CT.

Treatment

Surgery provides the best chance of a cure but should only be used only when imaging (see above) has shown that the tumour has not infiltrated outside the oesophageal wall. Less than 40% of patients will have potentially resectable disease at the time of presentation. Patients must be carefully evaluated preoperatively, particularly with regard to performance status (see p. 253), and surgery undertaken in designated units. Poor outcome data from surgery alone has challenged its role as monotherapy and it is more often used in conjunction with neo-adjuvant (preoperative) and adjuvant (postoperative) treatment.

Surgery provides the best chance of a cure but should only be used only when imaging (see above) has shown that the tumour has not infiltrated outside the oesophageal wall. Less than 40% of patients will have potentially resectable disease at the time of presentation. Patients must be carefully evaluated preoperatively, particularly with regard to performance status (see p. 253), and surgery undertaken in designated units. Poor outcome data from surgery alone has challenged its role as monotherapy and it is more often used in conjunction with neo-adjuvant (preoperative) and adjuvant (postoperative) treatment.

Chemoradiation. Preoperative (‘neo-adjuvant’) chemoradiation therapy may benefit patients with stage 2b and 3 disease. Prolongation of survival has been shown in some studies. In the USA neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is preferred to the neo-adjuvant chemotherapy that is typically used in the UK.

Chemoradiation. Preoperative (‘neo-adjuvant’) chemoradiation therapy may benefit patients with stage 2b and 3 disease. Prolongation of survival has been shown in some studies. In the USA neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is preferred to the neo-adjuvant chemotherapy that is typically used in the UK.

Palliative therapy is often the only realistic possibility. Dilatation is only of short-term benefit and the perforation risk is higher than for benign strictures. Combination of endoscopic dilatation with laser or brachytherapy (see p. 447) prolongs luminal patency and gives as good if not better functional results than stenting. Insertion of an expanding metal stent allows liquids and soft foods to be eaten.

Palliative therapy is often the only realistic possibility. Dilatation is only of short-term benefit and the perforation risk is higher than for benign strictures. Combination of endoscopic dilatation with laser or brachytherapy (see p. 447) prolongs luminal patency and gives as good if not better functional results than stenting. Insertion of an expanding metal stent allows liquids and soft foods to be eaten.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) can be useful in more superficial cancers.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) can be useful in more superficial cancers.

Chemoradiation alone is sometimes given, but evidence of benefit is poor except in early stage SCC.

Chemoradiation alone is sometimes given, but evidence of benefit is poor except in early stage SCC.

Nutritional support, as well as support for the patient and their family, is vital in this distressing condition.

Nutritional support, as well as support for the patient and their family, is vital in this distressing condition.

Other oesophageal tumours

Most other tumours are rare. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (see p. 253) and leiomyomas (both submucosal tumours) are found usually by chance; 10% cause dysphagia or bleeding. Surgical removal is performed for symptomatic lesions or those over 3 cm, which are more likely to harbour malignancy. Small benign tumours are relatively common and often do not require treatment.

Kaposi’s sarcoma is found in the oesophagus as well as the mouth (see p. 193) and hypopharynx in patients with AIDS.

FURTHER READING

Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP et al., MAGIC Trial Participants. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:11–20.

Okines A, Sharma B, Cunningham D. Perioperative management of esophageal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010; 7:231–238.

The stomach and duodenum

Structure

The stomach occupies a small area immediately distal to the oesophagus (the cardia), the upper region (the fundus, under the left diaphragm), the mid-region or body and the antrum, which extends to the pylorus (Fig. 6.8). It serves as a reservoir where food can be retained and broken up before being actively expelled in to the proximal small intestine.

The mucosal lining of the stomach can stretch in size with feeding. The greater curvature of the undistended stomach has thick folds or rugae. The mucosa of the upper two-thirds of the stomach contains parietal cells that secrete hydrochloric acid, and chief cells that secrete pepsinogen (which initiates proteolysis). There is often a colour change at the junction between the body and the antrum of the stomach that can be seen macroscopically, and confirmed by measuring surface pH.

The mucosal lining of the stomach can stretch in size with feeding. The greater curvature of the undistended stomach has thick folds or rugae. The mucosa of the upper two-thirds of the stomach contains parietal cells that secrete hydrochloric acid, and chief cells that secrete pepsinogen (which initiates proteolysis). There is often a colour change at the junction between the body and the antrum of the stomach that can be seen macroscopically, and confirmed by measuring surface pH.

The antral mucosa secretes bicarbonate and contains mucus-secreting cells and G cells, which secrete gastrin, stimulating acid production. There are two major forms of gastrin, G17 and G34, depending on the number of amino-acid residues. G17 is the major form found in the antrum. Somatostatin, a suppressant of acid secretion, is also produced by specialized antral cells (D cells).

The antral mucosa secretes bicarbonate and contains mucus-secreting cells and G cells, which secrete gastrin, stimulating acid production. There are two major forms of gastrin, G17 and G34, depending on the number of amino-acid residues. G17 is the major form found in the antrum. Somatostatin, a suppressant of acid secretion, is also produced by specialized antral cells (D cells).

Mucus-secreting cells are present throughout the stomach and secrete mucus and bicarbonate. The mucus is made of glycoproteins called mucins.

Mucus-secreting cells are present throughout the stomach and secrete mucus and bicarbonate. The mucus is made of glycoproteins called mucins.

The ‘mucosal barrier’, made up of the plasma membranes of mucosal cells and the mucus layer, protects the gastric epithelium from damage by acid and, for example, alcohol, aspirin, NSAIDs and bile salts. Prostaglandins stimulate secretion of mucus, and their synthesis is inhibited by aspirin and NSAIDs, which inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (see Fig. 15.30).

The ‘mucosal barrier’, made up of the plasma membranes of mucosal cells and the mucus layer, protects the gastric epithelium from damage by acid and, for example, alcohol, aspirin, NSAIDs and bile salts. Prostaglandins stimulate secretion of mucus, and their synthesis is inhibited by aspirin and NSAIDs, which inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (see Fig. 15.30).

The duodenal mucosa has villi like the rest of the small bowel, and also contains Brunner’s glands that secrete alkaline mucus. This, along with the pancreatic and biliary secretions, helps to neutralize the acid secretion from the stomach when it reaches the duodenum.

The duodenal mucosa has villi like the rest of the small bowel, and also contains Brunner’s glands that secrete alkaline mucus. This, along with the pancreatic and biliary secretions, helps to neutralize the acid secretion from the stomach when it reaches the duodenum.

Physiology

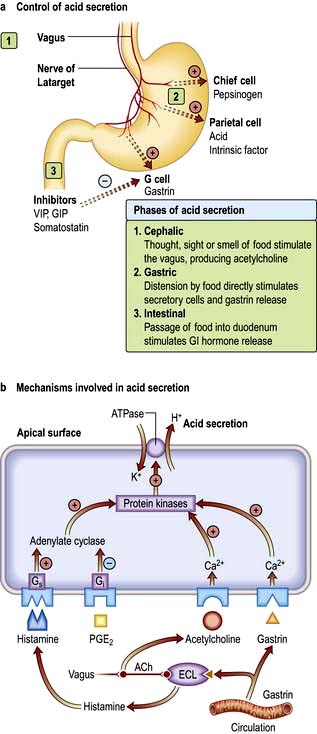

Acid secretion is central to the functionality of the stomach; factors controlling acid secretion are shown in Figure 6.15. Acid is not essential for digestion but does prevent some food-borne infections. It is under neural and hormonal control and both stimulate acid secretion through the direct action of histamine on the parietal cell. Acetylcholine and gastrin also release histamine via the enterochromaffin cells. Somatostatin inhibits both histamine and gastrin release and therefore acid secretion.

Gastritis and gastropathy

Autoimmune gastritis

This affects the fundus and body of the stomach (pangastritis), leading to atrophic gastritis and loss of parietal cells with achlorhydria and intrinsic factor deficiency causing the clinical syndrome of ‘pernicious anaemia’. Metaplasia, usually of the intestinal type, is almost always in the context of atrophic gastritis. Serum autoantibodies to gastric parietal cells are common and nonspecific: antibodies to intrinsic factor are rarer and more significant (see p. 382).

Helicobacter pylori infection

H. pylori is a slow-growing spiral Gram-negative flagellate urease-producing bacterium (Fig. 6.16) which plays a major role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. It colonizes the mucous layer in the gastric antrum, but is also found in the duodenum in areas of gastric metaplasia. H. pylori is found in greatest numbers under the mucous layer in gastric pits, where it adheres specifically to gastric epithelial cells. It is protected from gastric acid by the juxtamucosal mucous layer which traps bicarbonate secreted by antral cells, and ammonia produced by bacterial urease.

(Courtesy of Dr Alan Phillips, Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Royal Free Hospital.)

Pathogenesis

Results of infection

Duodenal ulcer (DU) (see Fig. 6.18a). The prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulceration is falling and in the developed world is now between 50% and 75%, whereas duodenal ulceration was once rare in the absence of H. pylori infection. This has been attributed to a decrease in prevalence of the bacteria and an increase in NSAID use. Eradication of the infection improves ulcer healing and decreases the incidence of recurrence.

Gastric ulcer (GU) (see Fig. 6.18b). Gastric ulcers are associated with a gastritis affecting the body as well as the antrum of the stomach (pangastritis) causing parietal cell loss and reduced acid production. The ulcers are thought to occur because of reduction of gastric mucosal resistance due to cytokine production by the infection or perhaps to alterations in gastric mucus.

Peptic ulcer disease

Clinical features of peptic ulcer disease

Examination is usually unhelpful; epigastric tenderness is common in non-ulcer dyspepsia.

Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection

Non-invasive methods

Serological tests detect IgG antibodies and are reasonably sensitive (90%) and specific (83%). They have been used in diagnosis and in epidemiological studies. IgG titres may take up to 1 year to fall by 50% after eradication therapy and therefore are not useful for confirming eradication or the presence of a current infection. Antibodies can also be found in the saliva, but tests are not as sensitive or specific as serology.

Serological tests detect IgG antibodies and are reasonably sensitive (90%) and specific (83%). They have been used in diagnosis and in epidemiological studies. IgG titres may take up to 1 year to fall by 50% after eradication therapy and therefore are not useful for confirming eradication or the presence of a current infection. Antibodies can also be found in the saliva, but tests are not as sensitive or specific as serology.

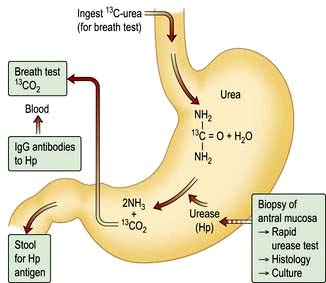

13C-Urea breath test (Fig. 6.17). This is a quick and reliable test for H. pylori and can be used as a screening test. The measurement of 13CO2 in the breath after ingestion of 13C urea requires a mass spectrometer. The test is sensitive (90%) and specific (96%), but the sensitivity can be improved by insuring the patient has not taken antibiotics in the 4 weeks prior and proton pump inhibitors in the 2 weeks before the test.

13C-Urea breath test (Fig. 6.17). This is a quick and reliable test for H. pylori and can be used as a screening test. The measurement of 13CO2 in the breath after ingestion of 13C urea requires a mass spectrometer. The test is sensitive (90%) and specific (96%), but the sensitivity can be improved by insuring the patient has not taken antibiotics in the 4 weeks prior and proton pump inhibitors in the 2 weeks before the test.

Stool antigen test. This is beginning to supersede breath testing as the method with which to determine H. pylori status. A specific immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies for the qualitative detection of H. pylori antigen is now widely available. The overall sensitivity is 97.6% with a specificity of 96%. It is useful in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection and for monitoring efficacy of eradication therapy. Patients should be off PPIs for 2 weeks but can continue with H2 blockers. Newer stool antigen tests are being developed that can be performed in the clinic setting, although at present the sensitivity and specificity are not as good as those performed in the laboratory.

Stool antigen test. This is beginning to supersede breath testing as the method with which to determine H. pylori status. A specific immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies for the qualitative detection of H. pylori antigen is now widely available. The overall sensitivity is 97.6% with a specificity of 96%. It is useful in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection and for monitoring efficacy of eradication therapy. Patients should be off PPIs for 2 weeks but can continue with H2 blockers. Newer stool antigen tests are being developed that can be performed in the clinic setting, although at present the sensitivity and specificity are not as good as those performed in the laboratory.

Invasive (endoscopy)

Biopsy urease test. Gastric biopsies, usually antral unless additional material is needed to exclude proximal migration, are added to a substrate containing urea and phenol red. If H. pylori are present, the urease enzyme that they produce splits the urea to release ammonia which raises the pH of the solution and causes a rapid colour change (yellow to red). This enables a patient’s H. pylori status to be determined before they leave the endoscopy suite. The test may be falsely negative if patients are taking PPIs or antibiotics at the time.

Biopsy urease test. Gastric biopsies, usually antral unless additional material is needed to exclude proximal migration, are added to a substrate containing urea and phenol red. If H. pylori are present, the urease enzyme that they produce splits the urea to release ammonia which raises the pH of the solution and causes a rapid colour change (yellow to red). This enables a patient’s H. pylori status to be determined before they leave the endoscopy suite. The test may be falsely negative if patients are taking PPIs or antibiotics at the time.

Histology. H. pylori can be detected histologically on routine (Giemsa) stained sections of gastric mucosa obtained at endoscopy. The sensitivity is reduced if a patient is on PPIs, but less so than with the urease test. This can be improved with immunohistochemical staining using an anti H. pylori antibody.

Histology. H. pylori can be detected histologically on routine (Giemsa) stained sections of gastric mucosa obtained at endoscopy. The sensitivity is reduced if a patient is on PPIs, but less so than with the urease test. This can be improved with immunohistochemical staining using an anti H. pylori antibody.

Culture. Biopsies obtained can be cultured on a special medium, and in vitro sensitivities to antibiotics can be tested. This technique is typically used for patients with refractory H. pylori infection to identify the appropriate antibiotic regimen and routine culture is rare.

Culture. Biopsies obtained can be cultured on a special medium, and in vitro sensitivities to antibiotics can be tested. This technique is typically used for patients with refractory H. pylori infection to identify the appropriate antibiotic regimen and routine culture is rare.

Investigation of suspected peptic ulcer disease

Patients under 55 years of age with typical symptoms of peptic ulcer disease who test positive for H. pylori can start eradication therapy without further investigation.

Patients under 55 years of age with typical symptoms of peptic ulcer disease who test positive for H. pylori can start eradication therapy without further investigation.

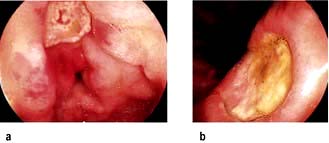

Endoscopic diagnosis and exclusion of cancer is required in older patients (Fig. 6.18). All gastric ulcers must be biopsied to exclude an underlying malignancy and should be followed up endoscopically until healing has taken place.

Endoscopic diagnosis and exclusion of cancer is required in older patients (Fig. 6.18). All gastric ulcers must be biopsied to exclude an underlying malignancy and should be followed up endoscopically until healing has taken place.

Endoscopy is required in all patients with ‘alarm symptoms’ (see p. 229).

Endoscopy is required in all patients with ‘alarm symptoms’ (see p. 229).

Eradication therapy

Current recommendations are that all patients with duodenal and gastric ulcers should have H. pylori eradication therapy if the bacteria is present. Many patients have incidental H. pylori infection with no gastric or duodenal ulcer. Whether all such patients should have eradication therapy is controversial (see Functional dyspepsia, p. 296).

There are many regimens for eradication, but all must take into account that:

There is a high incidence of resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin, particularly in some populations

There is a high incidence of resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin, particularly in some populations

FURTHER READING

Gisbert JP, Calvet X, O’Connor JP et al. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010; 11:905–918.

Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC et al.; Pylera Study Group. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011; 377:905–913.

Complications of peptic ulcer

Perforation (Box 6.4; see also p. 299)

The frequency of perforation of peptic ulceration is decreasing, partly attributable to medical therapy. DUs perforate more commonly than GUs, usually into the peritoneal cavity; perforation into the lesser sac also occurs. Detailed management of perforation is described on page 301. Laparoscopic surgery is usually performed to close the perforation and drain the abdomen. Conservative management using nasogastric suction, intravenous fluids and antibiotics is occasionally used in elderly and very sick patients.

Gastric outlet obstruction

Severe or persistent vomiting causes loss of acid from the stomach and a metabolic alkalosis (see p. 666). Vomiting will often settle with intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement, gastric drainage via a nasogastric tube and potent acid suppression therapy. Endoscopic dilatation of the pyloric region is useful, as is luminal stenting, and overall, 70% of patients can be managed without surgery.

Surgical treatment and its long-term consequences

No other procedure, such as gastrectomy or vagotomy, is required.

In the past, two types of operation were performed:

Vagotomy. Initially this was a truncal vagotomy and required a gastric drainage procedure such as pyloroplasty or gastro-jejunostomy. In later years, this was usually highly selective vagotomy or proximal gastric vagotomy, in which only the nerves supplying the parietal cells were transected, and therefore no drainage of the stomach was required.

Vagotomy. Initially this was a truncal vagotomy and required a gastric drainage procedure such as pyloroplasty or gastro-jejunostomy. In later years, this was usually highly selective vagotomy or proximal gastric vagotomy, in which only the nerves supplying the parietal cells were transected, and therefore no drainage of the stomach was required.

Long-term complications of surgery which are still seen occasionally include:

Recurrent ulcer. If this occurs, check for H. pylori; rule out Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (see p. 370). Malignancy needs to be excluded in all cases.

Recurrent ulcer. If this occurs, check for H. pylori; rule out Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (see p. 370). Malignancy needs to be excluded in all cases.

Dumping. This term describes a number of upper abdominal symptoms (e.g. nausea and distension associated with sweating, faintness and palpitations) that occur in patients following gastrectomy or gastroenterostomy. It is due to ‘dumping’ of food into the jejunum, causing rapid fluid shifts from plasma to dilute the high osmotic load with reduction of blood volume. The symptoms are usually mild and patients adapt to them. It is rare for it to be a long-term problem, and if so, the symptoms usually have a functional element. Hypoglycaemia can also occur.

Dumping. This term describes a number of upper abdominal symptoms (e.g. nausea and distension associated with sweating, faintness and palpitations) that occur in patients following gastrectomy or gastroenterostomy. It is due to ‘dumping’ of food into the jejunum, causing rapid fluid shifts from plasma to dilute the high osmotic load with reduction of blood volume. The symptoms are usually mild and patients adapt to them. It is rare for it to be a long-term problem, and if so, the symptoms usually have a functional element. Hypoglycaemia can also occur.

Diarrhoea was chiefly seen after vagotomy. Recurrent severe episodes occurred in about 1% of patients. Antidiarrhoeals are the usual treatment.

Diarrhoea was chiefly seen after vagotomy. Recurrent severe episodes occurred in about 1% of patients. Antidiarrhoeals are the usual treatment.

Nutritional complications: in the long term almost any gastric surgery, but particularly gastrectomy, may be followed by:

Nutritional complications: in the long term almost any gastric surgery, but particularly gastrectomy, may be followed by:

Other H. pylori-associated diseases

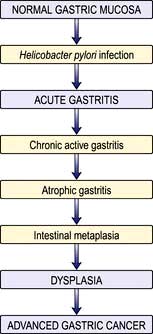

Gastric adenocarcinoma. The incidence of distal (but not proximal) gastric cancer parallels that of H. pylori infection in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. Serological studies show that people infected with H. pylori have a higher incidence of distal gastric carcinoma (see p. 252).

Gastric adenocarcinoma. The incidence of distal (but not proximal) gastric cancer parallels that of H. pylori infection in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. Serological studies show that people infected with H. pylori have a higher incidence of distal gastric carcinoma (see p. 252).

Gastric B cell lymphoma. Over 70% of patients with gastric B cell lymphomas (mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue – MALT) have H. pylori. H. pylori gastritis has been shown to contain the clonal B cell that eventually gives rise to the MALT lymphoma (see pp. 467 and 468).

Gastric B cell lymphoma. Over 70% of patients with gastric B cell lymphomas (mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue – MALT) have H. pylori. H. pylori gastritis has been shown to contain the clonal B cell that eventually gives rise to the MALT lymphoma (see pp. 467 and 468).

NSAIDs, Helicobacter and ulcers

Treatment

In many people with severe arthritis, stopping NSAIDs may not be possible. Therefore use:

An NSAID with low GI side-effects at lowest dose possible (see p. 511) or if there is no cardiovascular risk, a COX-2 NSAID can be used (see p. 511).

An NSAID with low GI side-effects at lowest dose possible (see p. 511) or if there is no cardiovascular risk, a COX-2 NSAID can be used (see p. 511).

Prophylactic cytoprotective therapy, e.g. PPI or misoprostol (a synthetic analogue of prostaglandin E1 800 µg/day) for all high-risk patients, i.e. over 65 years; those with a peptic ulcer history, particularly with complications, and patients on therapy with corticosteroids or anticoagulants. PPIs reduce the risk of endoscopic duodenal and gastric ulcers and are better tolerated than misoprostol, which causes diarrhoea.

Prophylactic cytoprotective therapy, e.g. PPI or misoprostol (a synthetic analogue of prostaglandin E1 800 µg/day) for all high-risk patients, i.e. over 65 years; those with a peptic ulcer history, particularly with complications, and patients on therapy with corticosteroids or anticoagulants. PPIs reduce the risk of endoscopic duodenal and gastric ulcers and are better tolerated than misoprostol, which causes diarrhoea.

Gastric tumours

Adenocarcinoma