5 Gastrointestinal disease

Symptoms

Dyspepsia and indigestion

Treatment

| Class of drug | Drug | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| H2-receptor antagonists | Cimetidine | 400 mg twice daily |

| Famotidine | 40 mg daily | |

| Nizatidine | 300 mg daily | |

| Ranitidine | 300 mg daily | |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Esomeprazole | 20 mg daily |

| Lansoprazole | 30 mg daily | |

| Omeprazole | 20 mg daily | |

| Pantoprazole | 40 mg daily | |

| Rabeprazole | 20 mg daily | |

| Antacids | Aluminium hydroxide | 10–20 mL 3 times daily |

| Magnesium carbonate | 10 mL 3 times daily | |

| Magnesium trisilicate | 10–20 mL 3 times daily | |

| Aluminium and magnesium complexes | 10 mL between meals and at bedtime | |

| Others | Alginates and antacids | 2 tablets twice daily |

| Chelates and complexes, e.g. tripotassium, dicitratobismuthate, sucralfate | 2 tablets twice daily |

Nausea and vomiting

Treatment

Many patients require no therapy. Food is usually withheld and fluids only are allowed. With more persistent vomiting, IV fluids, e.g. 0.9% saline (p. 369), are given for dehydration and correction of electrolyte abnormalities. A naso-gastric tube is inserted if there is bowel obstruction.

Diarrhoea

Acute diarrhoea

• Treatment

All produce constipation if given frequently.

• Specific therapy

Diarrhoea in patients with HIV infection

Chronic diarrhoea is a common symptom in patients with HIV infection (p. 96). Cryptosporidium is the commonest pathogen isolated. Other infective causes include cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium avium and Giardia intestinalis. Stool culture with examination for ova, cysts and parasites should be performed, together with flexible sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy and biopsy.

Chronic diarrhoea

Chronic diarrhoea refers to diarrhoea of more than 4 weeks’ duration. It can be due to a variety of causes (usually non-infective) including inflammation (inflammatory bowel disease), drugs (metformin, statins), functional factors, malabsorption or cancer (change in bowel habit), the treatments for which are described elsewhere.

• Clinical features

Constipation

Treatment

• Laxatives (Box 5.2)

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Reflux is extremely common in the general population, causing mild indigestion and heartburn.

Investigations

Under the age of 45 years, all patients should be treated initially without investigations, unless there are alarm symptoms (Box 5.1).

Treatment

• Medical treatment (Table 5.1)

Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)

These cases include patients with reflux symptoms. They often do not respond to a PPI. Patients are usually female and often the symptoms are functional (p. 167).

Complications

Other oesophageal disorders

Achalasia

Treatment

Diffuse oesophageal spasm

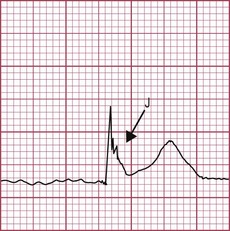

This disorder causes chest pain and dysphagia, is diagnosed by oesophageal manometry and is characterized by simultaneous non-peristaltic oesophageal contractions occurring after 20% or more swallows. Barium swallow may show a corkscrew appearance. Nutcracker oesophagus is a variant of diffuse oesophageal spasm characterized by very high-amplitude peristalsis (> 200 mmHg).

Chemical oesophagitis

Peptic ulcer disease

Helicobacter pylori

• Non-invasive:

Aspirin and other NSAIDs

Prophylactic therapy

This is necessary for all high-risk patients, i.e. those over 65 years, those with a peptic ulcer history, particularly with complications, and patients on therapy with corticosteroids or anticoagulants. An alternative is to give a COX-2 NSAID, which causes less mucosal damage (p. 298), but long-term cardiovascular risk is a problem.

Complications of peptic ulcer

These include haemorrhage (p. 151).

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

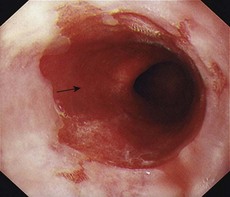

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Haematemesis is the vomiting of blood from a lesion proximal to the distal duodenum. Melaena is the passage of black tarry stools; the black colour is due to altered blood — 50 mL or more is required to produce this. Melaena can occur with bleeding from any lesion in areas proximal to and including the caecum.

Immediate management (Box 5.3)

Box 5.3 Management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding (see also Fig. 20.4)

| Endoscopic appearance | Risk |

|---|---|

| Active bleeding | 55% |

| Visible vessel | 45% |

| Adherent clot | 20% |

| Flat spot | 10% |

| Clean base | 5% |

Management of specific acute upper gastrointestinal disorders

Oesophagitis (10%)

As described on p. 140, this should be treated with high-dose oral PPI therapy, e.g. omeprazole 40 mg daily.

Oesophageal varices (10%)

• Pharmacotherapy

• Endoscopic therapy

Gastric varices

Peptic ulcers (50%)

Gastric and duodenal ulcers are the commonest cause of significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The risk of continued bleeding and rebleeding can be predicted on the basis of the endoscopic appearance of the ulcer (Box 5.3). This in turn determines the required medical and endoscopic therapy.

• Management

Erosive gastritis and duodenitis (10–20%)

This should be treated with oral PPI therapy and H. pylori eradication if the CLO test is positive.

GI haemorrhage in specific circumstances

Bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

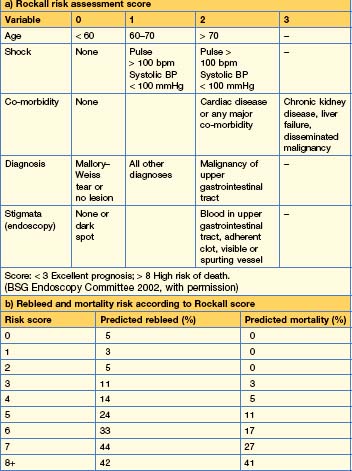

This occurs in approximately 2% of patients undergoing PCI (who are on antiplatelet therapy), and has a high mortality of 5–10%. Urgent endoscopy should be performed with appropriate therapy, for example, for an ulcer. A PPI should be given intravenously. Management is difficult, as cessation of antiplatelet therapy has a high risk of acute stent thrombosis and also an associated high mortality. Using a risk assessment score (e.g. Rockall, p. 148), a reasonable approach is to stop all antiplatelet therapy in high-risk patients but to continue in low-risk ones. These patients should be under the combined care of a cardiologist and a gastroenterologist.

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Massive bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract is rare. Conversely, small bleeds from haemorrhoids occur very commonly. Massive bleeding is usually due to diverticular disease or ischaemic colitis (p. 166).

Initial management

Initial management is similar to that of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (p. 146). Additional immediate investigations are rectal examination, proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy.

Management of specific acute lower gastrointestinal disorders

Angiodysplasia

This refers to abnormal blood vessels most commonly found in the caecum and proximal ascending colon. They are also associated with Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), renal disease, von Willebrand’s disease and aortic stenosis. Treatment is usually endoscopic, with thermal modalities and argon plasma coagulopathy (APC). In HHT, hormonal therapy with oestrogen–progesterones (oestradiol 0.035–0.05 mg; norethisterone 1 mg twice daily) has also been tried but evidence for efficacy is conflicting. Side-effects include gynaecomastia and erectile dysfunction.

Occult/chronic gastrointestinal bleeding

Initial investigations

If these investigations are normal, the patient can be treated with oral iron replacement therapy (p. 202) and only investigated further should anaemia recur.

Further investigations

Malabsorption

Coeliac disease

Investigations

Management

All patients with coeliac disease should be referred to a dietitian for a gluten-free diet (GFD). The avoidance of gluten should be emphasized even in the asymptomatic patient because of the increased risk of osteoporosis and malignancy (which is reduced by a strict diet). Folate deficiency is present in 50% of patients and iron deficiency is common; initial replacement therapy is given. Most patients respond to a GFD; a few require corticosteroids or azathioprine. All patients diagnosed with coeliac disease should undergo a bone densitometry scan (dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, DEXA) to assess for osteoporosis, which should be treated with bisphosphonates (p. 324), and monitored yearly. Pneumococcal vaccination is necessary due to the occurrence of splenic atrophy.

Massive intestinal resection (short-bowel syndrome)

Inflammatory bowel disease

Investigations

• Imaging

Drugs used in the treatment of IBD (Box 5.4)

Aminosalicylates

Box 5.4 Options for medical treatment of Crohn’s disease

• Formulations

• Indications

• Adverse effects

Corticosteroids

• Formulations

• Indications

Thiopurines

• Indications

• Adverse effects

Methotrexate

• Indications

Ciclosporin

• Indications

• Adverse effects

Biological agents/cytokine modulators

• Indications

Antibiotics

• Indications

Diet/lifestyle

Surgery

• Indications

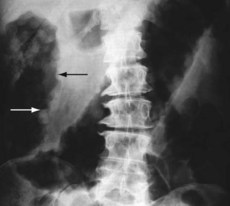

Acute severe colitis

Acute severe colitis can occur in patients with UC and CD (but remember it can also occur with C. difficile infection). It presents with diarrhoea (> 6 stools/day), fever > 37.5° and tachycardia > 90 bpm. Investigations show an anaemia (< 10 g/dL), a high ESR and a low serum albumin (< 30 g/L). A plain abdominal x-ray can show a thin-walled dilated colon (> 5 cm, or 8 cm in caecum) that is gas-filled and contains mucosal islands (toxic megacolon) (Fig. 5.2). Daily X-rays are required, as perforation occurs, with a mortality of up to 25%.

Treatment

Treatment is urgent and should be supervised by an experienced physician and colo-rectal surgeon. Fluid and electrolyte imbalance should be corrected. IV hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily is given. If there is no response in 48–72 hours and the CRP continues to be elevated > 45 mg/L, a second-line agent is commenced. Ciclosporin 2 mg/kg IV, accompanied by enteral nutrition for 5–7 days, can be used as a bridge to try to avoid surgery. Infliximab is used similarly (p. 161). The decision to proceed to surgery is often complex. In general, surgery is required if there is a toxic megacolon which does not respond rapidly to medical treatment, or if second-line treatment fails. If C. difficile infection is the cause of the severe colitis, do not treat with steroids and use vancomycin.

Colonic and anal disorders

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction

Clinical features

Symptoms include abdominal distension, colicky pain, absolute constipation, and nausea and vomiting.

Management

Diverticular disease

Investigations

Perianal disorders

Haemorrhoids

• Treatment

Functional gastrointestinal disorders

Functional oesophageal disorders (heartburn, chest pain of presumed oesophageal origin, dysphagia, globus)

Symptoms include heartburn (p. 139), chest pain and dysphagia. Dysphagia usually requires investigation with an endoscopy to exclude other oesophageal pathology. A barium swallow and oesophageal manometry help to exclude a motility disorder, e.g. achalasia. Globus describes an intermittent sensation of a lump in the throat.

Treatment

Functional gastroduodenal disorders (dyspepsia, belching, nausea and vomiting, rumination syndrome in adults)

Dyspepsia is the second commonest functional disorder, causing upper abdominal discomfort, bloating, early satiety and nausea. Nausea is common in association with functional gastrointestinal disorders but vomiting is rare. Self-induced vomiting compatible with an eating disorder should be excluded. OGD is required in patients > 55 years of age with a short history or alarm features (p. 134). Nausea does not warrant investigation, particularly in the young and in patients with no alarm symptoms. Simple blood tests may help to reassure the patient.

Treatment

• Pharmacotherapy

Functional bowel disorders (irritable bowel syndrome, bloating, constipation, diarrhoea)

Treatment

Pancreatic and biliary tract disease

Acute pancreatitis

Investigations

Assessment of severity

Multiple factors are used to develop scoring systems (Table 5.4). The Ranson and Glasgow scoring systems have been developed to predict severe cases of pancreatitis with a sensitivity of 80%. The APACHE scoring system has also been used.

Table 5.4 Factors during the first 48 hours that predict severe pancreatitis*

| Factor | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Age | >55 years |

| White cell count | >15 × 109/L |

| Blood glucose | >10 mmol/L (>180 mg/dL) |

| Serum urea | >16 mmol/L (>45 mg/dL) |

| Serum albumin | <30 g/L |

| Serum calcium | <2 mmol/L (<8 mg/dL) |

| Serum LDH | >600 U/L |

| Serum aspartate transferase | >200 U/L |

| PaO2 | <8.0 kPa (60 mmHg) |

| CRP | >150 mg/L |

Treatment

Complications

Chronic pancreatitis

Investigations

Treatment

Gallstones

Investigations

Common bile duct stones and acute cholangitis

Investigations

Management

The post-cholecystectomy syndrome refers to right upper quadrant pain recurring some time after cholecystectomy. This is occasionally due to stones in the common bile duct and occasionally to sphincter of Oddi dyskinesia. Patients with a dilated common bile duct and abnormal liver biochemistry should have an endoscopic sphincterotomy performed. In many patients the pain is functional (p. 173).

British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. 2007.

BSG Endoscopy Committee. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: guidelines. Gut. 2002;51(Suppl IV):1-6.

European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. 2010.

European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. Ulcerative colitis: current management. 2008.

Itanauer SB, et al. Accent! Trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dyspepsia guideline. 2004.

Rome III Gastroenterology 2006 Supplement.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines. Network (SIGN): Management of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. 2008.

Whitcomb DC. Acute pancreatitis. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150.