Chapter 315 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Most of the esophageal tests are of some use in particular patients with suspected GERD. Contrast (usually barium) radiographic study of the esophagus and upper gastrointestinal tract is performed in children with vomiting and dysphagia to evaluate for achalasia, esophageal strictures and stenosis, hiatal hernia, and gastric outlet or intestinal obstruction (Fig. 315-1). It has poor sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of GERD due to its limited duration and the inability to differentiate physiologic GER from GERD.

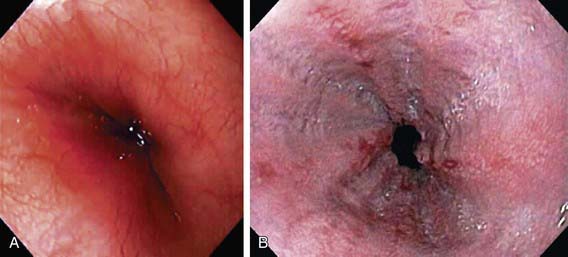

Endoscopy allows diagnosis of erosive esophagitis (Fig. 315-2) and complications such as strictures or Barrett esophagus; esophageal biopsies can diagnose histologic reflux esophagitis in the absence of erosions while simultaneously eliminating allergic and infectious causes. Endoscopy is also used therapeutically to dilate reflux-induced strictures. Radionucleotide scintigraphy using technetium can demonstrate aspiration and delayed gastric emptying when these are suspected.

Barron JJ, Tan H, Spalding J, et al. Proton pump inhibitor utilization patterns in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:421-427.

Campanozzi A, Boccia G, Pensabene L, et al. Prevalence and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux: Pediatric prospective survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123:779-783.

Chang AB, Lasscrson TJ, Gaffney J: Gastro-oesophageal reflux treatment for prolonged non-specific cough in children and adults (review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (1)CD004823, 2011.

Condino AA, Sondheimer J, Pan Z, et al. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux in pediatric patients with asthma using impedance-pH monitoring. J Pediatr. 2006;149:216-219.

Dent J. Pathogenesis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and novel options for its therapy. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:91-102.

Epstein D, Bojke L, Sculpher MJ, REFLUX Trial Group. Laparoscopic fundoplication compared with medical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: cost-effectiveness study. BMJ. 2009;339:152-155.

Farhath S, He Z, Nakhla T, et al. Pepsin, a marker of gastric contents, is increased in tracheal aspirates from preterm infants who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e253-e259.

Hassall E. Step-up and step-down approaches to treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:324-331.

Horvath A, Dzlechclarz P, Szajewska H. The effect of thickened-feed interventions on gastroesophageal reflux in infants: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1268-e1277.

Internation Pediatric Endosurgery Group Standard and Safety Committee. IPEG guidelines for the surgical treatment of pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19(1):x-xiii.

Kane TD. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Minerva Chir. 2009;64:147-157.

Orenstein SR, Hassall E, Furmagae-Jablonska W, et al. Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole in infants with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr. 2009;154:514-520.

Orenstein SR, McGowan JD. Efficacy of conservative therapy as taught in the primary care setting for symptoms suggesting infant gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2008;152:310-314.

Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Kelsey SF, Frankel E. Natural history of infant reflux esophagitis: symptoms and morphometric histology during one year without pharmacotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:628-640.

Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, et al. A global evidence based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278-1295.

Srivastava R, Berry JG, Hall M, et al. Reflux related hospital admissions after fundoplication in children with neurological impairment: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 340, 2010. b4411 doi:10.1136/bmj.b4411

Thompson M, Antao B, Hall S, et al. Medium term outcome of endoluminal gastroplication with the EndoCinch device in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:172-177.

Van Zanten SV. Dyspepsia and reflux in primary care: rough DIAMOND of a trial. Lancet. 2009;373:187-188.

315.1 Complications of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Ali Mel-S. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: diagnosis and treatment of a controversial disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:28-33.

El-Serag HB, Gilger MA, Shub MD, et al. The prevalence of suspected Barrett’s esophagus in children and adolescents: a multicenter endoscopic study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:671-675.

Gilger MA, El-Serag HB, Gold BD, et al. Prevalence of endoscopic findings of erosive esophagitis in children: a population based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:141-146.

Havemann BD, Henderson CAA, El-Serag HB. The relationship between gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and asthma; a systematic review. Gut. 2007;56:1654-1664.

Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett’s oesophagus. Lancet. 2009;373:850-858.

Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277-2288.

Slocum C, Hibbs AM, Martin RJ, Orenstein SR. Infant apnea and gastroesophageal reflux: a critical review and framework for further investigation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:219-224.

Tolia V, Vandenplas Y. Systematic review: the extra-oesophageal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:258-272.

Vaezi MF. Laryngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Gastroenterol Reports. 2008;10:271-277.

Valusek PA, St Peter SD, Tsao K, et al. The use of fundoplication for prevention of apparent life-threatening events. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1022-1024.

Vandenplas Y, Rudolph C, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498-547.