Gastroenterology

Features of gastrointestinal disorders in children are:

• Vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea are common and usually transient; serious causes are uncommon but important to identify

• Worldwide, gastroenteritis is responsible for 1.2 million deaths/year, one of the commonest causes of death in children <5 years old

• The number of children and adolescents developing inflammatory bowel disease is increasing

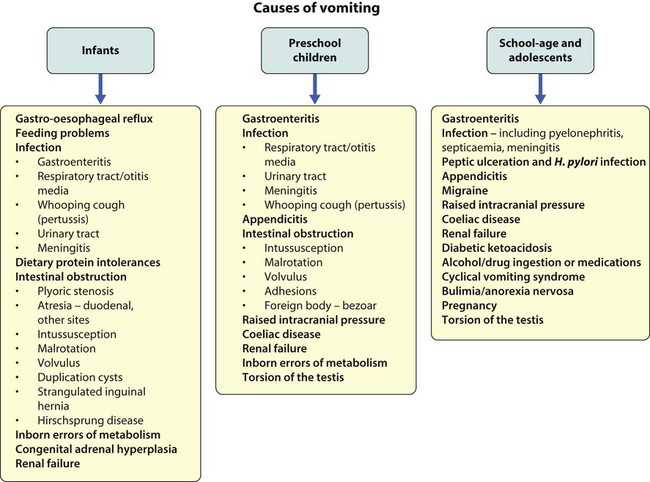

Vomiting

Vomiting is the forceful ejection of gastric contents. It is a common problem in infancy and childhood (Fig. 13.1 and Box 13.1).

It is usually benign and is often caused by feeding disorders or mild gastro-oesophageal reflux or gastroenteritis. Potentially serious disorders need to be excluded if the vomiting is bilious or prolonged, or if the child is systemically unwell or failing to thrive. In infants, vomiting may be associated with infection outside the gastrointestinal tract, especially in the urinary tract and central nervous system. In intestinal obstruction, the more proximal the obstruction, the more prominent the vomiting and the sooner it becomes bile-stained (unless the obstruction is proximal to the ampulla of Vater). Intestinal obstruction is associated with abdominal distension, more marked in distal obstruction. ‘Red Flag’ clinical features suggesting significant organic pathology are listed in Box 13.1.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Complications are listed in Box 13.2.

Severe reflux is more common in:

• children with cerebral palsy or other neurodevelopmental disorders, when energetic management, surgical if necessary, may transform the child’s quality of life

• preterm infants, especially if coexistent bronchopulmonary dysplasia

• following surgery for oesophageal atresia or diaphragmatic hernia.

Investigation

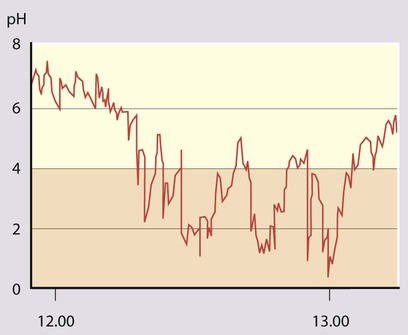

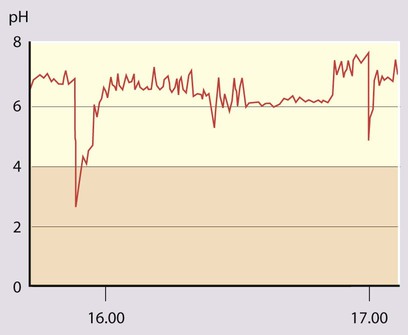

• 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring to quantify the degree of acid reflux (see Case History 13.1).

• 24-hour impedance monitoring. Available in some centres. Weakly acidic or non-acid reflux, which may cause disease, is also measured.

• Endoscopy with oesophageal biopsies to identify oesophagitis and exclude other causes of vomiting.

Pyloric stenosis

• Vomiting, which increases in frequency and forcefulness over time, ultimately becoming projectile

• Hunger after vomiting until dehydration leads to loss of interest in feeding

Diagnosis

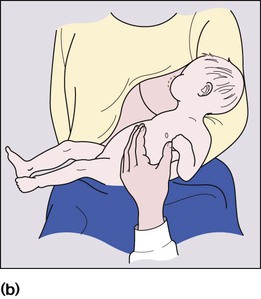

Unless immediate fluid resuscitation is required, a test feed is performed. The baby is given a milk feed, which will calm the hungry infant, allowing examination. Gastric peristalsis may be seen as a wave moving from left to right across the abdomen (Fig. 13.3a). The pyloric mass, which feels like an olive, is usually palpable in the right upper quadrant (Fig. 13.3b). If the stomach is overdistended with air, it will need to be emptied by a nasogastric tube to allow palpation. Ultrasound examination is helpful (Fig. 13.3c) if the diagnosis is in doubt.

Management

The initial priority is to correct any fluid and electrolyte disturbance with intravenous fluids (0.45% saline and 5% dextrose with potassium supplements). Once hydration and acid–base and electrolytes are normal, definitive treatment by pyloromyotomy can be performed. This involves division of the hypertrophied muscle down to, but not including, the mucosa (Fig. 13.3d). The operation can be performed either as an open procedure via a periumbilical incision or laparoscopically. Postoperatively, the child can usually be fed within 6 h and discharged within 2 days of surgery.

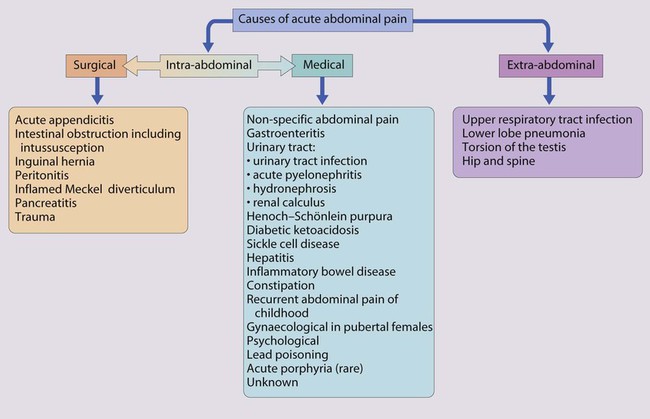

Acute abdominal pain

Assessment of the child with acute abdominal pain requires considerable skill. The differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in children is extremely wide, encompassing non-specific abdominal pain, surgical causes and medical conditions (Fig. 13.4). In nearly half of the children admitted to hospital, the pain resolves undiagnosed. In young children it is essential not to delay the diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis, as progression to perforation can be rapid. It is easy to belittle the clinical signs of abdominal tenderness in young children. Of the surgical causes, appendicitis is by far the most common. The testes, hernial orifices and hip joints must always be checked. It is noteworthy that:

• Lower lobe pneumonia may cause pain referred to the abdomen

• Primary peritonitis is seen in patients with ascites from nephrotic syndrome or liver disease

• Diabetic ketoacidosis may cause severe abdominal pain

• Urinary tract infection, including acute pyelonephritis, is a relatively uncommon cause of acute abdominal pain, but must not be missed. It is important to test a urine sample, in order to identify not only diabetes mellitus but also conditions affecting the liver and urinary tract.

Acute appendicitis

Acute appendicitis is the commonest cause of abdominal pain in childhood requiring surgical intervention (Fig. 13.5). Although it may occur at any age, it is very uncommon in children <3 years old. The clinical features of acute uncomplicated appendicitis are:

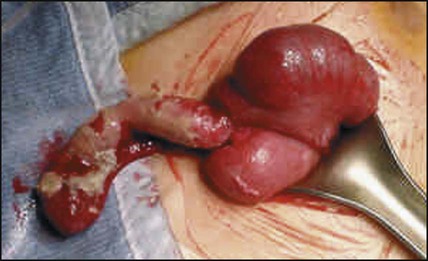

Intussusception

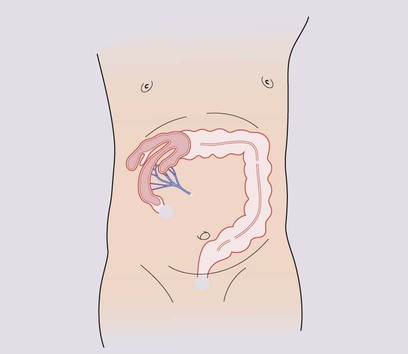

Intussusception describes the invagination of proximal bowel into a distal segment. It most commonly involves ileum passing into the caecum through the ileocaecal valve (Fig. 13.6a). Intussusception is the commonest cause of intestinal obstruction in infants after the neonatal period. Although it may occur at any age, the peak age of presentation is between 3 months and 2 years. The most serious complication is stretching and constriction of the mesentery resulting in venous obstruction, causing engorgement and bleeding from the bowel mucosa, fluid loss and subsequently bowel perforation, peritonitis and gut necrosis. Prompt diagnosis, immediate fluid resuscitation and urgent reduction of the intussusception are essential to avoid complications.

Presentation is typically with:

• Paroxysmal, severe colicky pain and pallor – during episodes of pain, the child becomes pale, especially around the mouth, and draws up his legs. He initially recovers between painful episodes, but subsequently becomes increasingly lethargic

• May refuse feeds, may vomit, which may become bile-stained depending on the site of the intussusception

• A sausage-shaped mass – often palpable in the abdomen (Fig. 13.6b)

• Passage of a characteristic redcurrant jelly stool comprising blood-stained mucus – this is a characteristic sign but tends to occur later in the illness and may be first seen after a rectal examination

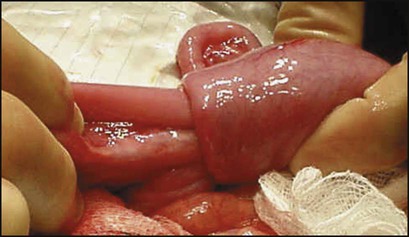

An X-ray of the abdomen may show distended small bowel and absence of gas in the distal colon or rectum. Sometimes the outline of the intussusception itself can be visualised. Abdominal ultrasound is helpful both to confirm the diagnosis and to check response to treatment. Unless there are signs of peritonitis, reduction of the intussusception by rectal air insufflation is usually attempted by a radiologist (Fig. 13.6c). This procedure should only be carried out once the child has been resuscitated and is under the supervision of a paediatric surgeon in case the procedure is unsuccessful or bowel perforation occurs. The success rate of this procedure is about 75%. The remaining 25% require operative reduction (Fig. 13.6d). Recurrence of the intussusception occurs in less than 5% but is more frequent after hydrostatic reduction.

Meckel diverticulum

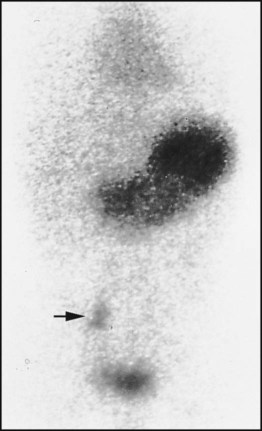

Around 2% of individuals have an ileal remnant of the vitello-intestinal duct, a Meckel diverticulum, which contains ectopic gastric mucosa or pancreatic tissue. Most are asymptomatic but they may present with severe rectal bleeding, which is classically neither bright red nor true melaena. Other forms of presentation include intussusception, volvulus around a band, or diverticulitis which mimics appendicitis. A technetium scan will demonstrate increased uptake by ectopic gastric mucosa in 70% of cases (Fig. 13.7). Treatment is by surgical resection.

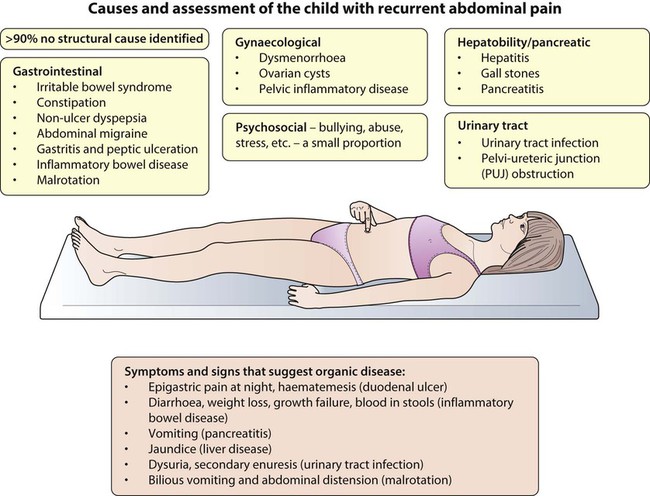

Recurrent abdominal pain

Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) is a common childhood problem. It is often defined as pain sufficient to interrupt normal activities and lasts for at least 3 months. It occurs in about 10% of school-age children. A cause (see Summary box) is identified in <10%.The pain is characteristically periumbilical and the children are otherwise entirely well. The widely held belief that they have psychogenic pain is without foundation, a number of studies having failed to show a difference between such children and their families and controls. In some children, it may however be a manifestation of stress (see Chapter 23) or it may become part of a vicious cycle of anxiety with escalating pain leading to family distress and demands for increasingly invasive investigations. There is evidence that anxiety may lead to altered bowel motility, which may be perceived by the child as pain.

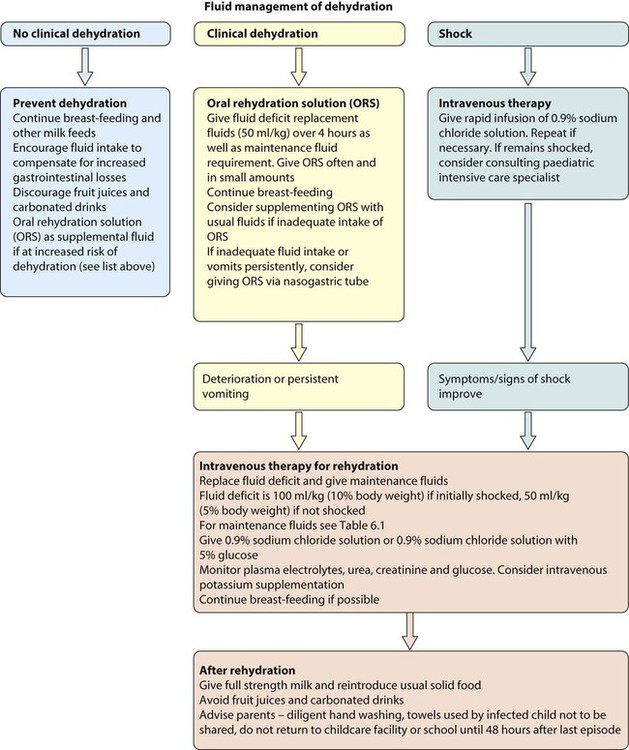

Gastroenteritis

In gastroenteritis there is a sudden change to loose or watery stools often accompanied by vomiting. There may be contact with a person with diarrhoea and/or vomiting or recent travel abroad. A number of disorders may masquerade as gastroenteritis (Box 13.3) and, when in doubt, hospital referral is essential. Dehydration leading to shock is the most serious complication and its prevention or correction is the main aim of treatment.

The following children are at increased risk of dehydration:

• Infants, particularly those under 6 months of age or those born with low birthweight.

• If they have passed ≥6 diarrhoeal stools in the previous 24 h

• If they have vomited three or more times in the previous 24 h

• If they have been unable to tolerate (or not been offered) extra fluids

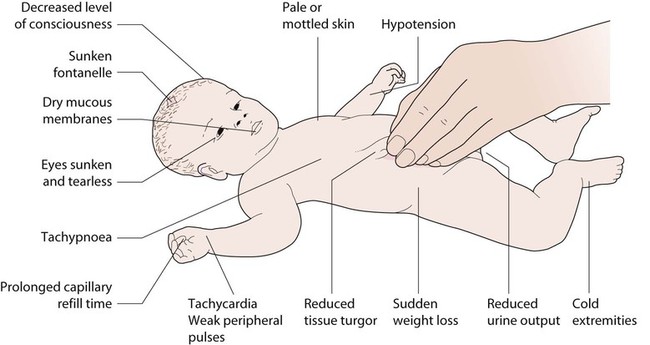

Assessment

• No clinically detectable dehydration (usually <5% loss of body weight)

• Clinical dehydration (usually 5–10%)

• Shock (usually >10%) (Fig. 13.9 and Table 13.1). Shock must be identified without delay.

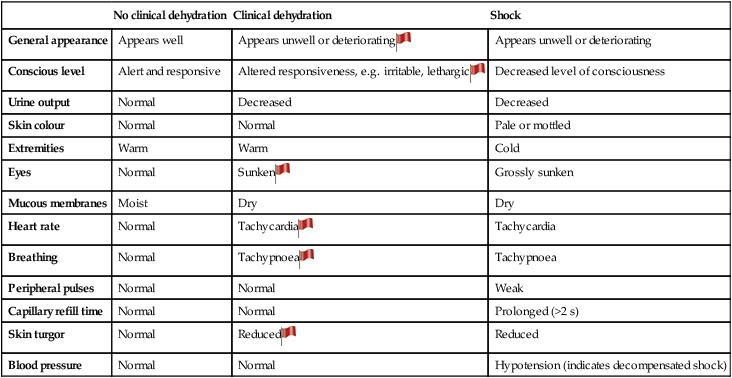

Table 13.1

Clinical assessment of dehydration

| No clinical dehydration | Clinical dehydration | Shock | |

| General appearance | Appears well | Appears unwell or deteriorating |

Appears unwell or deteriorating |

| Conscious level | Alert and responsive | Altered responsiveness, e.g. irritable, lethargic |

Decreased level of consciousness |

| Urine output | Normal | Decreased | Decreased |

| Skin colour | Normal | Normal | Pale or mottled |

| Extremities | Warm | Warm | Cold |

| Eyes | Normal | Sunken |

Grossly sunken |

| Mucous membranes | Moist | Dry | Dry |

| Heart rate | Normal | Tachycardia |

Tachycardia |

| Breathing | Normal | Tachypnoea |

Tachypnoea |

| Peripheral pulses | Normal | Normal | Weak |

| Capillary refill time | Normal | Normal | Prolonged (>2 s) |

| Skin turgor | Normal | Reduced |

Reduced |

| Blood pressure | Normal | Normal | Hypotension (indicates decompensated shock) |

; ‘Red Flag’ sign – helps to identify children at risk of progression to shock.

; ‘Red Flag’ sign – helps to identify children at risk of progression to shock.

The more numerous and more pronounced the symptoms and signs, the greater the severity of dehydration.

From NICE Guideline, Diarrhoea and vomiting in children, 2009.

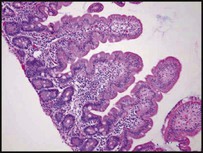

Malabsorption

Disorders affecting the digestion or absorption of nutrients manifest as:

• failure to thrive or poor growth in most but not all cases

• specific nutrient deficiencies, either singly or in combination.

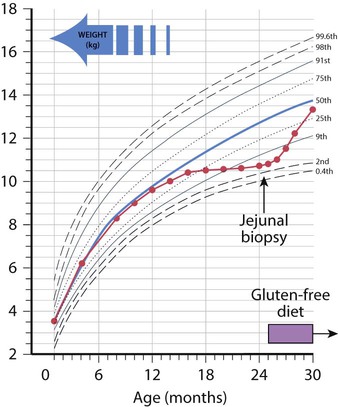

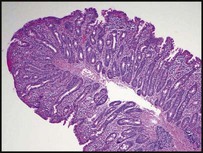

Coeliac disease

The classical presentation is of a profound malabsorptive syndrome at 8–24 months of age after the introduction of wheat-containing weaning foods. There is failure to thrive, abdominal distension and buttock wasting abnormal stools and general irritability (see Case History 13.2). However, this is no longer the most common presentation and children are now more likely to present less acutely in later childhood. The clinical features of coeliac disease can be highly variable and include mild, non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms, anaemia (iron and/or folate deficiency) and growth failure. Alternatively, it is identified on screening of children at increased risk (type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroid disease, Down syndrome) and first-degree relatives of individuals with known coeliac disease.

Inflammatory bowel disease

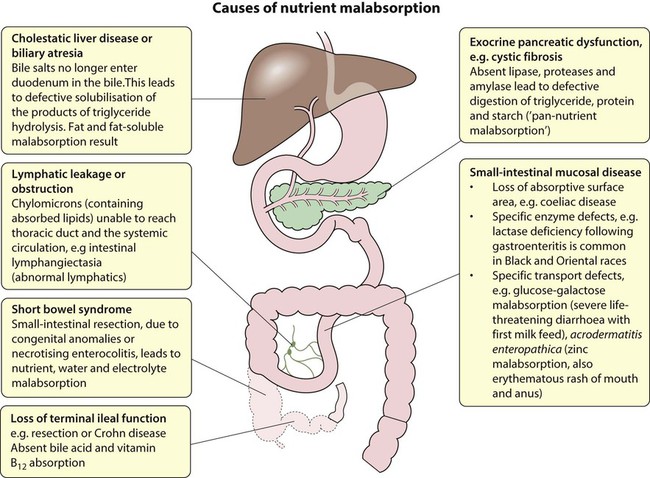

Crohn disease

The clinical features of Crohn disease are summarised in Figure 13.13. Lethargy and general ill health without gastrointestinal symptoms can be the presenting features, particularly in older children. There may be considerable delay in diagnosis as it may be mistaken for psychological problems. It may also mimic anorexia nervosa. The presence of raised inflammatory markers (platelet count, ESR and CRP), iron deficiency anaemia and low serum albumin are helpful in both making a diagnosis and confirming a relapse.

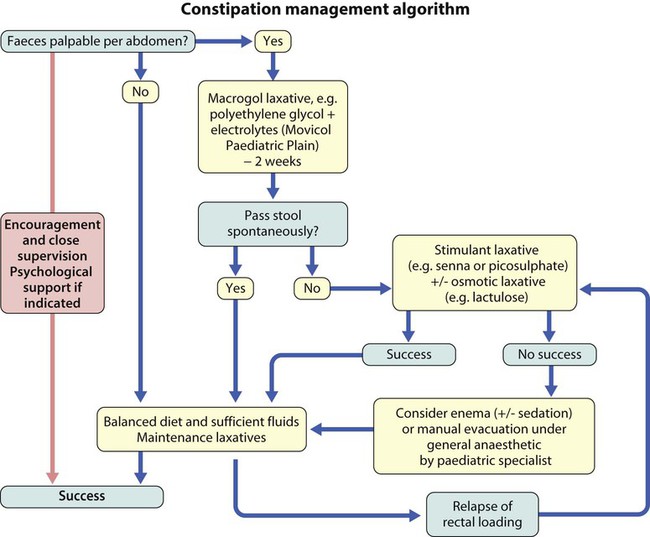

Constipation

Constipation is an extremely common reason for consultation in children. Parents may use the term to describe decreased frequency of defecation; the degree of hardness of the stool and painful defecation. The ‘normal’ frequency of defecation is highly variable and varies with age. Infants have an average of four stools per day in the first week of life, but this falls to an average of two per day by 1 year of age. Breast-fed infants may not pass stools for several days and be entirely healthy. By 4 years of age, children usually have a stool pattern similar to adults, in whom the normal range varies from three stools per day to three stools per week. A pragmatic definition of constipation is the infrequent passage of dry, hardened faeces often accompanied by straining or pain. There may be abdominal pain which waxes and wanes with passage of stool or overflow soiling (see Chapter 23, Emotions and behaviour).

Examination often reveals a palpable abdominal mass in a well-looking child. Digital rectal examination should only be performed by a paediatric specialist and only if a pathological cause is suspected. ‘Red Flag’ symptoms and signs indicative of more significant pathology are detailed in Box 13.4. Investigations are not usually required to diagnose idiopathic constipation, but are carried out as indicated by history or clinical findings.

In more long-standing constipation, the rectum becomes overdistended, with a subsequent loss of feeling the need to defecate. Involuntary soiling may occur as contractions of the full rectum inhibit the internal sphincter, leading to overflow. Management of these children is likely to be more difficult and protracted (Fig. 13.14). Children of school age are frequently teased as a result and secondary behavioural problems are common.

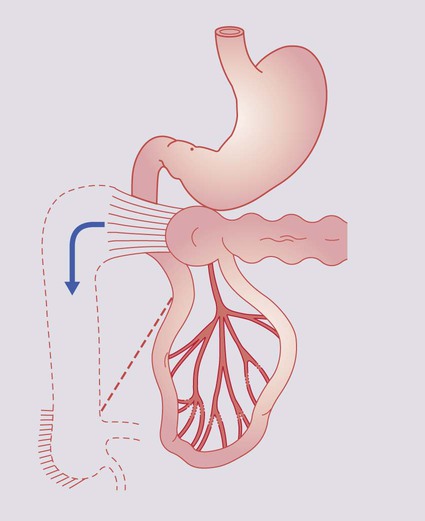

Hirschsprung disease

The absence of ganglion cells from the myenteric and submucosal plexuses of part of the large bowel results in a narrow, contracted segment. The abnormal bowel extends from the rectum for a variable distance proximally, ending in a normally innervated, dilated colon. In 75% of cases, the lesion is confined to the rectosigmoid, but in 10% the entire colon is involved. Presentation is usually in the neonatal period with intestinal obstruction heralded by failure to pass meconium within the first 24 h of life. Abdominal distension and later bile-stained vomiting develop (Fig. 13.15). Rectal examination may reveal a narrowed segment and withdrawal of the examining finger often releases a gush of liquid stool and flatus. Temporary improvement in the obstruction following the dilatation caused by the rectal examination can lead to a delay in diagnosis.