4 Gastroenterology

Vomiting

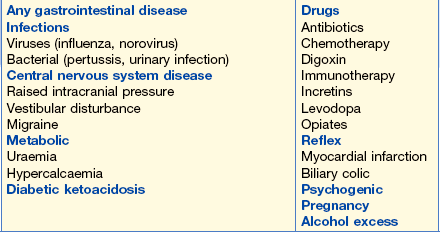

Causes of vomiting are shown in Table 4.1.

• Chest X-ray (CXR). Normal. Look for evidence of air under the diaphragm (perforation), signs of pneumonia, hilar mass (tumour).

• Abdominal X-ray (AXR). Normal. With a history of this length, a normal X-ray would suggest that large or small bowel obstruction is unlikely. High obstruction in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, i.e. in the oesophagus or stomach, is possible. Investigate for non-GI causes (metabolic, neurological – exclude brainstem lesion), occasionally severe depression.

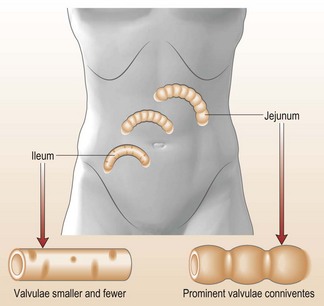

In this patient, the AXR showed small bowel obstruction (Fig. 4.1). The differential diagnosis is shown in the Information box.

Management

The ultimate goal is to relieve obstruction. In the interim:

Weight loss

What should you do?

• Hyperthyroidism: check for symptoms and signs of hyperthyroidism (see p. 434).

• Alcoholic liver disease (see p. 70).

• Malnutrition: check by asking the patient’s family. Perhaps there is a psychiatric history?

• Underlying cancer, particularly lung, bowel and pancreas.

• Biochemical investigations: should help determine underlying metabolic or renal disease.

• Malabsorption: often causes anorexia, which contributes to weight loss.

This patient had no major signs of chronic liver disease but did admit to recurrent episodes of upper abdominal pain radiating through to his back. These tended to occur on Monday, following his weekend binges. This suggests pancreatic disease resulting from his heavy alcohol intake.

What initial investigations are appropriate?

• FBC, LFTs, calcium, blood alcohol

• Plain X-ray of the abdomen for pancreatic calcification

• Abdominal ultrasound to assess the pancreas for cysts and potential masses.

This patient was admitted in a malnourished, hyperdynamic state due to acute alcohol withdrawal (see p. 72). Treat this initially and further investigate the pancreas later.

Dysphagia

What should you do?

Unfortunately, this woman developed severe chest pain immediately after the dilatation and surgical emphysema could be felt in her neck. Clinically, an oesophageal tear is suspected.

A CXR with a water soluble contrast agent orally, confirms an oesophageal rupture.

Initial management

Small tears in a peptic stricture can resolve in a few days on conservative management. Large tears generally need surgery in a dedicated thoracic unit. Endoscopic stenting is used initially for tears in malignant lesions but again surgery may be required.

Biopsies later confirmed a squamous carcinoma.

Management will include assessment for surgery with:

• Blood count, liver biochemistry

• Abdominal US, CT scan to assess operability

• Endoscopic ultrasound is an accurate way of staging lesion and any local lymph nodes

Discussion should take place at an MDT to decide on the patient’s treatment.

Constipation

This is the infrequent passage of stools, < 3 per week + straining and the passage of hard stools.

Treatment

• Initially, the patient will require a laxative to ‘get things moving’. Glycerol suppositories are useful. Oral magnesium sulphate, an osmotic purgative, is effective and cheaper than the more usually prescribed osmotic laxative lactulose.

• Do not use stimulant laxatives.

• Stop ‘constipating’ drugs if possible.

• Faecal impaction might require digital extraction followed by small-volume phosphate enemas.

• Advise the patient regarding high-fibre diets and fluid intake.

Diarrhoea

What should you do in a case of diarrhoea presenting in A&E?

• Determine frequency, consistency, content of stool, presence of blood.

• Determine the state of hydration and electrolyte balance.

• Send stool for culture, parasites (ova or cysts) and C. difficile toxin (if the patient has previously been hospitalised or been on antibiotics).

• Perform a rectal examination; sigmoidoscopy (if bloody diarrhoea) should be done by the gastroenterology team.

Management

This will depend on the case scenario (see below) but most diarrhoeal illnesses are self-limiting and short lived; 1–10% might persist for a month. Identification of the pathogen will determine specific therapy (see Chapter 1).

What immediate action would you take?

• Send stools for ova, cysts and culture.

• Rehydration with oral glucose/electrolyte solutions initially. IV fluids are usually not necessary.

• Vomiting might need to be treated with an anti-emetic (metoclopramide 10 mg × 3/day).

What is the differential diagnosis?

• Infective diarrhoea. Send specimens for microbiological testing.

• First presentation of inflammatory bowel disease (most likely in this woman).

What should you do?

General

• Take blood for FBC, ESR, CRP, urea and electrolytes, liver biochemistry.

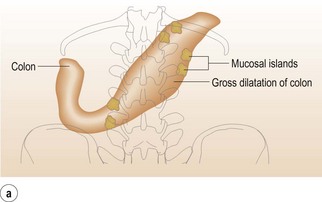

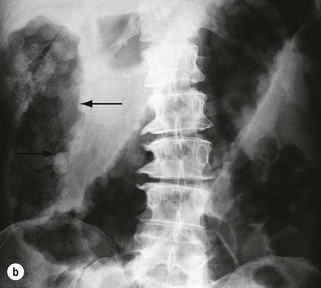

• Check plain abdominal X-ray for presence of stool, mucosal oedema, bowel dilatation or perforation.

• Sigmoidoscopy: the presence of an inflamed, friable mucosa with loss of vascular pattern or a patchy inflammation indicates inflammatory bowel disease. Take a rectal biopsy.

• Stool cultures (NB: Infective gastroenteritis must always be ruled out). C. difficile toxin assay – 4 stool specimens (90% sensitivity).

In this patient you have ruled out infective gastroenteritis as three stool cultures were negative. Taking into account the history and the sigmoidoscopic finding, you presume this must be inflammatory bowel disease. Her Hb was 100 g/L and CRP 84 mg/L.

Acute colitis is associated with diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever and systemic disturbance. There is blood in the stools in ulcerative colitis but Crohn’s disease patients only have bloody diarrhoea with Crohn’s colitis. To assess severity, check the factors shown in Table 4.2.

| Haemoglobin | ↓ | < 100 g/L |

| Albumin | ↓ | < 30 g/L |

| Fever | ↑ | > 37.5°C |

| Stool frequency | ↑ | > 6/day |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | ↑ | > 30 mm per hour |

| Pulse rate | ↑ | > 90 bpm |

| Platelets | ↑ | |

| White blood cells | ↑ |

How would you manage this acute situation?

• IV fluids with glucose/saline.

• IV therapy with steroids (IV hydrocortisone 100 mg × 4/day) followed by oral therapy (enteric coated prednisolone 40 mg per day) if patient improves.

• IV antibiotics (metronidazole/cephalosporin).

• Further management: refer to gastroenterologists; consult GI surgeons.

Has this patient got Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis?

Both can produce an acute colitis. The differentiation is by colonoscopy and histological appearance (see Table 4.3).

Table 4.3 Differentiating between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Histological findings | Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | Deep (transmural), patchy | Superficial (mucosal) continuous |

| Granulomas | + + | Rare |

| Goblet cells | Present | Depleted |

| Crypt abscesses | + | + + |

Information

Both

Table 4.4 Extra-gastrointestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease

| Eyes | Uveitis |

| Episcleritis, conjunctivitis | |

| Joints | Type I (pauci-articular) arthropathy |

| Type II (polyarticular) arthropathy | |

| Arthralgia | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Inflammatory back pain | |

| Skin | Erythema nodosum |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum (see Fig. 4.3) | |

| Liver and biliary tree | Sclerosing cholangitis |

| Fatty liver | |

| Chronic hepatitis | |

| Cirrhosis | |

| Gallstones | |

| Nephrolithiasis | |

| Venous thrombosis |

Abdominal pain

Management

Develop the management plan to include:

• Information for patient and relatives.

• Further investigations (endoscopy, ultrasound, CT and MRI as necessary to exclude perforation, obstruction, stones, calcification, cancer and ascites).

In this case, abdominal pain situated in the epigastrium and central abdomen, and of the severity described, is always due to organic disease. Your differential diagnosis should include the following:

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

Case history

A 48-year-old man was admitted with severe epigastric pain radiating up into his chest. He thought he had had a heart attack (see p. 284).

What investigations would you do on admission?

Progress and management

Remember

• Reflux can be difficult to diagnose and although it is often associated with a hiatus hernia, more formal investigation might be necessary, e.g. endoscopy followed by oesophageal pH, impedance and pressure monitoring if necessary

• At endoscopy, assess degree of oesophagitis and check for Barrett’s oesophagus (including biopsies).

Peptic ulcer disease

What would you do next?

You would need to establish whether the patient has had successful H. pylori eradication.

Tests for Helicobacter pylori

• Serological IgG antibodies (useful in the community but does not distinguish between past or current infections).

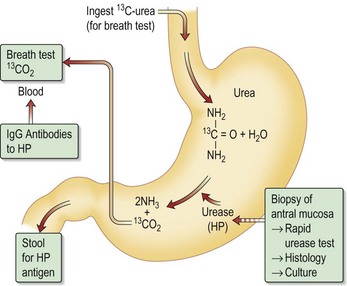

• Urea breath tests (for current infections) measuring 13CO2 (Fig. 4.4).

• Antral biopsy: either for histology or for CLO (urease) testing (for current infections).

This patient’s urea breath test is positive, indicating continuing H. pylori infection.

Treatment of H. pylori infection

With increasing resistance to clarithromycin, quadruple therapy is now being used, as in this patient. He was given omeprazole 20 mg × 2, tri-potassium di-citrato bismuthate 120 mg × 4, tetracycline 500 mg × 4 and metronidazole 500 mg × 3 – all daily for 2 weeks.

How do you investigate a patient with a suspected ulcer in the community?

• Less than 45 years: H. pylori serology. If positive, eradication therapy (see p. 48). If negative, treat symptomatically.

• Greater than 45 years: patients with new dyspepsia and those with alarm symptoms (e.g. anorexia, weight loss) should be referred for endoscopy.

Remember

• H. pylori serology can remain positive even after successful eradication of H. pylori

• Current H. pylori infection can be detected by the urea breath test (see Fig. 4.4), endoscopy (urease test, histology or culture) and detection of stool antigen.

Case history (2)

A bleeding ulcer might have certain stigmata that suggest rebleeding is likely to recur (see Remember box).

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht IV/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664.

2011 Managing acute upper GI bleeding. BSG Tool kit. Lancet. 2011;377:1048.

Gralnek IM, Baskin AN, Bardon M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. NEJM. 2006;359:928–937.

Iron deficiency anaemia

What do you do?

• Exclude all obvious causes of bleeding:

• If there is no obvious menorrhagia, you can assume the anaemia is due to gastrointestinal disease. Malabsorption: coeliac disease is still very underdiagnosed.

• The patient travels a lot abroad and could have a bowel infestation. Remember hookworm is the most common cause of iron deficiency anaemia world-wide.

• Occult bleeding from the GI tract is common and can be confirmed by haemoccult testing. This, however, is totally unnecessary in a patient with iron deficiency because if there is no history of blood loss, blood can then only be lost from the GI tract.

What additional investigations are appropriate?

• Rectal examination is mandatory to exclude rectal cancer. Proctoscopy to exclude piles.

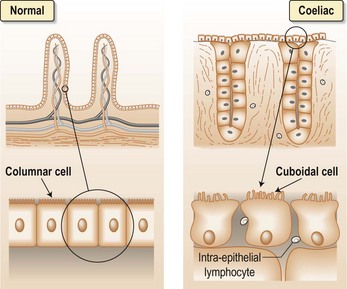

• Gastroscopy: peptic ulcer, gastric cancer and GORD can certainly occur in this age group. Also do a duodenal biopsy for coeliac disease (see Fig. 4.5).

Remember

Coeliac disease:

• Is increasingly recognised world-wide and has an incidence of less than 1:100 in many countries. Certain areas of the world are said to have a higher incidence, e.g. Ireland and Italy

• Malabsorption of iron as well as increased iron loss can occur. There might be other deficiencies as well, e.g. calcium and folic acid

• A history of steatorrhoea can be missed unless a detailed stool history is taken (Note: many patients do not have steatorrhoea or any gastrointestinal symptoms)

• Coeliac serology with anti-endomysial and anti-tissue transglutaminase (the target antigen for the endomysial antibody) antibodies. A serum IgA must be performed as these are IgA in vitro tests. Deaminated gluten peptide (DGP) testing is now becoming available. These tests have a high sensitivity and specificity.

• Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy of duodenal/jejunal mucosa

If gastroscopy is unhelpful, full colonic assessment is necessary. The best investigation is colonoscopy, which will allow full assessment of the colon when biopsy, polypectomy, laser treatment of angiodysplasia can be performed as appropriate.

• Angiography: preferably performed when a patient is bleeding and in this patient unlikely to be helpful

• Laparotomy with possibly simultaneous on-table endoscopy at the time.

Rectal bleeding is characterised by the passage of fresh blood rectally as opposed to either occult loss when blood can only be detailed by laboratory testing or melaena (see p. 66).

How would you manage the patient initially?

The patient stabilised and had no further bleeding.

Family history of colon cancer

What should you advise?

Familial adenomatous polyposis: multiple polyps are found throughout the colon and upper small bowel. All patients should be screened after age 12 years because all patients will develop colon cancer unless the colon is removed.

Hereditary non-polyposis cancer of the colon (HNPCC) (Table 4.5): this accounts for 5–10% of colon cancers; the average age of diagnosis is 45 years. Cancers are mainly in the right-hand side of the colon.

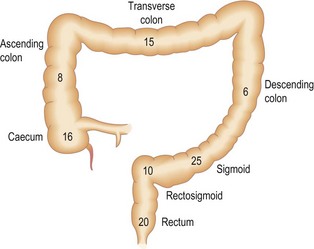

A flexible sigmoidoscope can only reach 60–70 cm up the colon, where approximately 60% of cancers occur (Fig. 4.6).

Table 4.5 Diagnostic criteria for hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC)

← Colorectal cancer diagnosed in patient who is younger than 50 years

← Presence of synchronous, metachronous colorectal, or other HNPCC-associated tumours, irrespective of age

← Colorectal cancer with the MSI-H ↑ histology ↑ diagnosed in a patient who is younger than 60 years

← Colorectal cancer diagnosed in one or more first degree relatives with an HNPCC-related tumour, with one of the cancers being diagnosed under the age 50 years

← CRC diagnosed in two or more first or second degree relatives with HNPCC-related tumours, irrespective of age

MSI-H, microsatellite instability – high.

Functional bowel disease

What do you do?

• Re-take the history with the possibility of this being irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

• Re-examine the abdomen: think of all the causes of an acute abdomen again (see Information box).

The history strongly supports the diagnosis of IBS. Remember that the pain can be very severe and real to the patient even though it is related to life events, i.e. the pain is not just ‘all in the mind’.