Chapter 5. Gastroenterology

Introduction

Other medical conditions also present with gastrointestinal symptoms: on our unit, we have recently seen two young patients presenting with acute abdominal pain, one with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and the other with meningococcal meningitis. Acute myocardial infarction, basal pneumonia and pulmonary embolus are all known to masquerade as an acute abdomen from time to time. More commonplace is the problem of nausea and vomiting – common diagnostic dilemmas in themselves, but also occurring as accompanying symptoms in diseases as diverse as cerebral haemorrhage and septicaemia.

The Acute Medical Unit nurse must be familiar with the causes and clinical course of the common acute gastrointestinal emergencies, in particular with the complications that can occur in the first 24h and which often determine whether the patient will recover. Nurses must also have a working knowledge of the common gastrointestinal symptoms that they will encounter – what will be the likely cause and what will be the best form of management.

Nausea and Vomiting Underlying Mechanisms

Nausea is one of the most distressing acute symptoms, but it is easy to relieve, provided that:

• the underlying mechanism is understood

• the cause is identified and corrected

• the appropriate drugs are used

Vomiting is a common but potentially serious problem:

• it can occur in response to a minor illness, but it can indicate serious disease

• it can itself lead to metabolic problems

The Patient Who is Vomiting: The General Approach

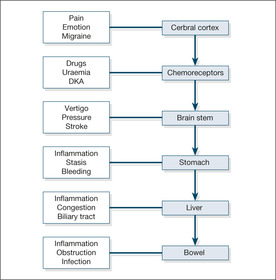

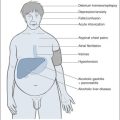

Consider the underlying mechanisms and potential causes (→Fig. 5.1)

Local gastrointestinal causes include acute gastritis and gastroenteritis (especially staphylococcal food poisoning), liver inflammation and cholecystitis.

Establish the history

• Did it occur in the setting of another illness?

• Is there pain anywhere?

• What other symptoms are present (e.g. headache, giddiness, abdominal pain)?

• Has it happened before?

• Has anyone else got the same symptoms?

Is this gastrointestinal disease?

• Is there any diarrhoea?

• Is there or has there been any abdominal pain? (Try to identify abdominal pain other than that due to the mechanical effects of retching.) Vomiting is a common feature of cholecystitis and pancreatitis

• Are there any features of obstruction (absolute constipation, cramps, abdominal distension, a tender lump in the groin may be a strangulated hernia)?

• Is the cause acute liver damage (hepatitis or paracetamol overdose)?

• Is there alcohol abuse?

Is this drug-related?

• What drugs have been started or increased in recent days?

• Is this digoxin toxicity/opiate side-effect?

Could this be raised intracranial pressure?

• What is the accompanying clinical setting?

— headache (meningitis/subarachnoid haemorrhage)?

— malignant disease (cerebral secondaries)?

— altered consciousness level (cerebral mass/encephalitis, etc.)?

Could this be metabolic?

• Is there renal failure?

• Are the sodium and calcium levels normal?

• Could this be ketoacidosis (the patient may be diabetic)?

Nausea and Vomiting in Acute Medical Conditions

Migraine

Migraine is commonly accompanied by vomiting. Other more worrying causes of headache – meningitis, increased intracranial pressure and subarachnoid haemorrhage – are also associated with vomiting, so the symptom itself is of little diagnostic help in this setting. In these situations, other features such as a skin rash or stroke-like symptoms help to clarify the underlying diagnosis.

Myocardial infarction

Vomiting is an important feature that distinguishes the pain of a myocardial infarction from that of angina and is often accompanied by nausea and sweating. In the elderly patient, vomiting may be the only symptom of a myocardial infarction.

Sepsis

Vomiting can be the only symptom of hidden infection, even of frank septicaemia, particularly in the elderly or immunocompromised patient. This is particularly the case in infections in the kidneys and lower urinary tract.

Acute gastric dilatation

Acute gastric dilatation is important because it is an easily preventable cause of sudden death. In this condition, gross gastric distension leads to upper abdominal swelling associated with nausea, often accompanied by hiccups and belching. These patients are often already unwell and a common outcome is sudden vomiting, aspiration and cardiorespiratory arrest. Factors that can trigger acute gastric dilatation include electrolyte disturbance, bacterial toxins and, most commonly, DKA. Treatment is simple – anticipate the possibility (in DKA, in severe infection and in any critically ill patient), recognise the condition, and prevent aspiration by decompressing the stomach with a nasogastric tube.

Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common cause for acute admission. In a catchment population of 200 000, around 300 acute gastrointestinal bleeds will be admitted per year. Some will be trivial (a young man who has light blood streaking after repeated vomiting the ‘morning after’) and can be discharged home very quickly. The majority will be of moderate severity, can undergo endoscopy on the next available list and will stop bleeding of their own accord. A minority, however, will be lifethreatening and complex: a truly multidisciplinary approach will be needed, involving gastroenterologists, radiologists, surgeons and several junior doctors.

At the centre, in the severe cases, is the nurse. It is the nurse who will be the first to assess the initial blood loss, who will personally witness any rebleeding and who will be on the ward at critical times – when the patient returns from endoscopy, when the consultant surgeon arrives seeking an urgent update and in the early hours when the observations deteriorate. Also caught up in the frenetic activity will be a critically ill patient who, possibly in a confused and agitated state, may be frightened and uncertain about what is going on. The nurse’s role is:

• to ensure the immediate safety of the patient

• to assess the degree of initial blood loss

• to collect information for assessing the risk to the patient of the bleed

• to identify the earliest signs of re-bleeding

• to coordinate the management of fluid replacement, transfusions and fluid balance

• to reassure the patient and ensure that there is appropriate symptomatic relief

The are some critical issues in the presentation and management of gastrointestinal bleeding on the Acute Medical Unit:

• early diagnosis and adequate resuscitation are the keys to successful management

• patients with significant haemodynamic disturbance or who need transfusion will need urgent endoscopy

• patients who do badly are older, lose a larger quantity of blood and either continue to bleed or stop and then bleed again

• there is an overall mortality rate of 8–10%, which has not improved in recent years

• the mortality risk is almost entirely confined to patients over 60 years and with significant co-morbidity

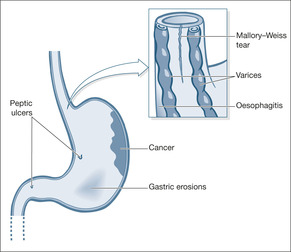

Causes of Acute Bleeding

The success of the management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding lies in making an early diagnosis of its likely source. Unfortunately, there are several potential bleeding sites: from the oesophagus to the duodenum in patients with haematemesis and from the oesophagus to the beginning of the colon in patients with melaena. The cause of the bleeding determines the outlook: some types (e.g. gastric erosions) will always stop bleeding on their own; some will often need intervention (e.g. varices) (→Fig. 5.2). Once the initial bleed has settled, some lesions will have resolved completely (e.g. Mallory-Weiss tears), whereas others have a high risk of re-bleeding (e.g. arterial bleeds from a peptic ulcer). Diagnosis rests on knowing the likely source, bearing in mind the patient’s age (→Box 5.1) and history and, most importantly, the findings at early endoscopy – which ideally means within the first 24h of admission.

Box 5.1

| Young | Old |

|---|---|

| Mallory-Weiss tears– – – – – – Varices – – – – – – | Gastric/oesophageal cancer |

| Duodenal ulcer | Gastric ulcer |

| Acute gastritis | Oesophageal ulcer |

| Acute duodenitis | Oesophagitis |

Peptic ulcer disease

Duodenal and gastric ulcers are the causes in half of all cases of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Most ulcers (eight out of ten) stop bleeding of their own accord; the remainder need intervention at endoscopy (injection of the ulcer base with adrenaline (epinephrine)/coagulation with a heat probe or laser/clipping), in the radiology department (embolisation), or possibly by surgery. After a bleed patients require a three week ulcer-healing course of lanzoprazole or omeprazole followed, if the patient has to re-start on NSAIDS or aspirin, by maintenance therapy.

Helicobacter pylori infection and bleeding peptic ulcers

About 60–70% of all gastric ulcers and 80% or more of all duodenal ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection within the stomach (most of the remainder are associated with use of NSAIDs). Eradication of the infection speeds ulcer healing and, of importance to the Acute Medical Unit, if the ulcer has bled, eradication lessens the risk of re-bleeding. Eradication therapy is simple – a week of ampicillin, omeprazole and clarithromycin – and should be started once the patient returns from endoscopy if the patient has a duodenal ulcer and tests on the endoscopic specimens are H. pylori positive. This aspect of management is frequently neglected. The situation with bleeding gastric ulcers is more controversial and in most cases re-endoscopy is advisable 6 weeks after the initial bleed, at which time tests for H. pylori can be performed and eradication therapy given if necessary.

Acute gastritis, duodenitis and acute erosions (‘stress ulcers’)

Acute gastric and duodenal erosions are common in patients taking NSAIDs and aspirin. Although they can cause massive blood loss, the bleeding will stop provided the patient survives the initial event. The two major issues are adequate resuscitation and ensuring that the blood loss is not arising from a more serious source such as a chronic ulcer or varices.

Mallory-Weiss tear

Acute oesophageal mucosal tears can be diagnosed from the history: patients retch and vomit several times before noticing that one of their vomits contains a varying amount of fresh blood. The patients are usually young, and acute alcohol intake is often involved. The bleeding can be heavy and the patients can be very alarmed. The outlook is almost universally excellent, with the bleeding stopping of its own accord and the tear healing completely within 24h.

Oesophageal varices

Less common, but more frightening for everyone concerned, oesophageal varices account for around 10% of acute bleeds. Blood loss can be massive and can itself result in death, but more commonly it triggers acute liver failure – in patients whose livers are already performing badly. Varices need active intervention to stop them bleeding and to reduce the risk of a re-bleed. Overall death rates are high, up to 30%. Fortunately, there have been important improvements in the field using endoscopic (injection sclerotherapy and banding) and radiological (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic anastomosis) techniques. It is to the general relief of many that the Sengstaken tube is now making progressively fewer appearances on the medical ward.

Gastric and oesophageal cancer

Gastric and oesophageal cancer occur in older patients, and the bleeding is often preceded by a history of weight loss, anorexia and, in the case of oesophageal cancer, swallowing difficulty.

Dieulafoy’s erosion

This rare cause of massive bleeding is due to erosion of a congenitally abnormal artery in the lining of the stomach. Emergency surgery is often required.

Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

Ensuring the safety of the patient: ABCDE

The consciousness level may be impaired, either as part of shock (poor cerebral blood supply) or because the bleeding has occurred in a patient with liver disease and has triggered liver failure. However, unless the bleeding has taken place, say, as a stress reaction to an acute stroke, the airway is unlikely to be at risk.

Administer high-flow oxygen immediately if the patient is hypotensive or has a pulse over 100 beats/min – on the assumption there has been a major bleed. Monitor the oxygen saturations to assess the response.

Check the patient for any pain: severe abdominal pain is unusual in upper gastrointestinal bleeding and needs urgent medical assessment. In the elderly, blood loss can readily trigger an anginal attack or even cause myocardial infarction.

Anticipate that large-bore i.v. cannulae (e.g. grey Venflons®) will be inserted into both arms and that either immediate saline or polygeline (Haemaccel®) may be needed. If there is haemodynamic disturbance (e.g. pulse 110 beats/min, systolic blood pressure 100mmHg, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min), it would be appropriate to give 2L of isotonic saline rapidly and then, if there is no improvement, consider polygeline (Haemaccel®), as at least 20% of the blood volume will have been lost.

Who needs urgent endoscopy?

Young patients with minor gastrointestinal bleeding in whom there is no change in pulse or blood pressure can be safely discharged and do not require endoscopy. Most other patients with gastrointestinal bleeding can safely be endoscoped on the next available endoscopy list. Indeed, the risks of emergency endoscopy in an inadequately resuscitated patient in the middle of the night can outweigh the potential advantage. However, urgent endoscopy to establish the site of blood loss, assess the risk of re-bleeding and attempt endoscopic haemostasis is required:

• when oesophageal varices are suspected

• after massive bleeding

• in the high-risk elderly

• when the problem is a re-bleed

Assessing the degree of bleeding

The history is invaluable in assessing blood loss:

• haematemesis with melaena indicates greater bleeding than either alone

• clots in the vomit and recognisable blood in the stool both indicate heavy bleeding

• postural dizziness and overwhelming thirst suggest a major bleed

The examination adds supporting evidence to the history. However, the patient’s age will influence the signs – a young person can lose 500ml or more of blood before any of the observations change, but a similar loss in an elderly person would have a major impact. The patient with major bleeding characteristically:

• is pale and clammy

• has a tachycardia of more than 100 beats/min

• has a systolic blood pressure of less than 100mmHg

• shows postural hypotension, with a 20+ mmHg fall in the systolic pressure on sitting

Assessing the risk to the patient from the bleed (→Case Study 5.1)

Age – is the patient over 60 years of age? The mortality rate in upper gastrointestinal bleeding is 20 times higher in the elderly than in the young:

• the underlying causes are more serious (e.g. gastric ulcers and gastric cancer)

• pre-existing heart disease may complicate the effects of acute blood loss

Case Study 5.1

An 84-year-old independent man presented with two syncopal episodes followed by a large vomit of recognisable blood. He had a 1-week history of upper abdominal pain and was taking regular low-dose aspirin.There was a past history of chronic angina and Type II diabetes.

On admission the patient was pale, alert and orientated with blood visible around the mouth.The pulse was 80 beats/min and the blood pressure 135/65mmHg lying and 80/35mmHg sitting.There was mild epigastric tenderness and rectal examination revealed soft brown stool.

The initial assessment was of an acute upper gastrointestinal bleed in a highrisk elderly man with ischaemic heart disease. Haemaccel®, 2 units, was given while awaiting the first of 6 units of blood that were ordered.The surgeons were contacted and agreed to visit ‘if there was a second bleed’. A central line was inserted.

Three hours after admission the patient vomited 500ml of fresh blood. Emergency endoscopy showed a 1.5-cm deep gastric ulcer.This ulcer was not actively bleeding and was injected with adrenaline (epinephrine).Twenty-four hours later the patient appeared to be stable, having had a total of 5 units of blood. A second endoscopy was ordered by the surgeons and showed a ‘spurting vessel’; this was re-injected.After this the patient’s condition remained stable. Surgery was planned in the event of further bleeding.

Six days after admission the patient had a sudden massive bleed and suffered a cardiac arrest.The patient aspirated blood into the lungs. Resuscitation was unsuccessful and the patient died.

Amount – small, moderate or large? The initial assessment of pulse, blood pressure and direct observation should be interpreted in combination with the results from the endoscopy. Clearly, the finding of ‘a spurting arterial bleed from the base of a chronic gastric ulcer’ is much more significant than ‘no visible blood in the stomach or duodenum’.

Is there another complicating condition present? The three most important diseases that will influence the chances of recovery are:

• liver failure (abnormal clotting, varices, encephalopathy)

• kidney failure (worsened by acute blood loss and reduced renal blood flow)

• heart failure (impairs the corrective responses to blood loss, increases the risks of transfusion)

Is there an underlying malignancy? This may be the direct source of the bleeding, or the bleeding may be from stress ulceration caused indirectly by a malignancy elsewhere. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is quite a common problem in terminal malignant disease.

Risk assessment with the Rockall Score

The Rockall Score is used to distinguish between those patients who can be discharged early without endoscopy and those in whom, without emergency intervention, there is a high risk of re-bleeding and death. Patients are scored before and after endoscopy (→Table 5.1).

| Score 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age | 60 | 60–79 | 80+ | |

| shock? | Pulse < 100 SBP > 100 |

Pulse > 100 SBP > 100 |

SBP < 100 | |

| co-morbidity? | nil | CCF, IHD, other major conditions | renal failure, liver failure, metastases | |

| diagnosis | Mallory-Weiss | all other | GI cancer | |

| Endoscopic signs of bleeding | no bleeding | fresh blood, clot, spurting |

When the pre-endoscopy score is 0 it is generally safe to discharge the patient early without urgent endoscopy – a higher score requires early endoscopy. A full (post-endoscopy) score of <3 indicates a low risk of re-bleeding or death and these patients can be considered for accelerated discharge.

Looking for evidence of re-bleeding

There are several endoscopic features that predict a high risk of re-bleeding:

• active arterial bleeding (90% risk)

• a vessel visible at the base of an ulcer (50% risk)

• an adherent clot over an ulcer crater (30% risk)

Features that indicate re-bleeding are fresh haematemesis or melaena associated with disturbed haemodynamics – a pulse rate over 100 beats/min, a systolic pressure less than 100mmHg, a fall in CVP more than 5cmH2O or a fall in haemoglobin of more than 2g in 24h. Depending on the underlying diagnosis, patients who re-bleed will need further endoscopic procedures and, if these are unsuccessful, a second re-bleed will almost certainly lead to emergency surgery. Reliable, well-charted observations are critical in the close monitoring of these patients during the first 48h of their admission. The pulse rate is the single most useful measurement, as it is the first to change if the patient re-bleeds (or remains high if bleeding does not stop in the first place). The drop in blood pressure lags behind the increase in pulse rate, although a postural decrease also provides a useful early warning. Halfhourly observations are needed in the first 4h after an acute bleed.

In major bleeds, the CVP provides the most reliable guide to re-bleeding, because it falls before there is any increase in the pulse rate. It is invaluable in the elderly in whom the risks are high and other factors such as betablocker therapy and cardiac arrhythmias render the pulse rate unreliable as a sign of blood loss (→Case Study 5.2).

Case Study 5.2

An 87-year-old woman was admitted with haematemesis and melaena. Endoscopy showed oesophagitis, pyloric stenosis and a bleeding duodenal ulcer, which was injected, with apparent success. At 01.00h her pulse suddenly increased from 100 to 140 beats/min and her blood pressure fell acutely. There were no external signs of further bleeding. Her ECG showed rapid atrial fibrillation at 140 beats/min. She remained hypotensive for half an hour before she reverted spontaneously to normal rhythm, when her pulse and blood pressure also normalised. She did not re-bleed after admission and made a good recovery. Any acute illness in the elderly can trigger rapid atrial fibrillation, which in itself can lead to a sudden, but reversible, deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The patient described in Case Study 5.1 is typical of the type of patient who is commonly admitted to the acute medical wards. He was at high risk because of:

Many personnel were involved, and the patient needed extremely close monitoring. Characteristically, there was uncertainty over the indications and timing of surgery – in circumstances in which a clear management plan from the outset is a fundamental requirement. An early, combined and well-documented consultation between the physicians, surgeons and nursing staff is invaluable in cases such as this, in which the risks of major complications can be anticipated from the moment the patient is first seen.

While difficult management decisions are being considered, it is also critical that the nurse is focused on the immediate condition of the patient:

• Quarter-hourly observations may be necessary during the first few hours after a massive bleed to determine whether the bleeding has stopped. These can be reinstated at the first sign of re-bleeding (e.g. a fall in a previously stable CVP or a large fresh melaena stool).

• Reassuring signs are a decrease in the pulse rate and reduction in any postural hypotension.

• The respiratory rate is raised in shock, but will also increase if the patient develops pulmonary oedema due to over-transfusion – this is a particular risk in an elderly patient with pre-existing heart disease who has needed vigorous resuscitation with fluids and blood.

Intensive monitoring and urgent investigative procedures are likely to lead to disorientation and distress in these elderly patients. Constant reassurance is needed, combined with careful explanations of the various interventions and staff that the patient is suddenly encountering. It will be a great comfort to the patient to be able to identify at least one familiar face among the frenetic activity of the first 12–24h. Patients with significant blood loss are extremely weak and debilitated. If there is frequent melaena, the effort of calling for, and using, a commode at short notice will be exhausting (and often extremely embarrassing) for the patient. Nursing staff have to be readily available to assist the patient and to deal with the distress of melaena or haematemesis with sensitivity and professionalism.

Intravenous pantoprazole/omeprazole?

High dose i.v. proton pump inhibitors pantoprazole/omeprazole 80mg stat and 8mg per hour for 72 hours are only used in patients who have had a major bleed from a peptic ulcer. Treatment is started after the patient has returned from endoscopic haemostatic therapy.

Role of the nurse in facilitating communication

Case Study 5.3 illustrates how poor communication can affect a patient’s treatment. This was a very high-risk case due to the bleeding source, the age of the patient and the pre-existing health of the patient. There was good early liaison with the surgeons, but the problems arose because of the quality of the communication. An issue as simple as the orientation of an endoscope photograph had serious consequences and underlines the enormous value of effective communication. In this case, it would have been invaluable to have had a senior member of the surgical team present at the endoscopy.

Case Study 5.3

A 71-year-old woman was admitted with major upper gastrointestinal bleeding: there were large fresh clots in her vomit bowl and dark red blood mixed in with melaena. A week before admission an exercise test had been aborted because of early ischaemic changes on her ECG. She had also suffered a myocardial infarction 6 months previously. Emergency endoscopy revealed a typical Dieulafoy anomaly with a visible arterial bleed, high in the lesser curve.

After unsuccessful attempts at endoscopic injection and embolisation she was taken as an emergency to theatre.There was no direct communication between the senior surgeon and the endoscopist; much of the information transfer was either through a third party or from the endoscopy form, which itself was filled out ambiguously. Furthermore the first operation, a partial gastrectomy, was done under adverse conditions with the patient actively bleeding and hypotensive.The lesion was not included in the resected gastric tissue. She continued to bleed after surgery and so further surgery with a total gastrectomy was done. She made an uneventful recovery after this.

The nurse is in an ideal position to facilitate the liaison between surgeons and physicians.

• Are the observations and transfusion charts clearly documented and displayed so that the surgeons can judge whether the patient is still bleeding or is re-bleeding?

• Is the most recent bowel action/vomit available to be seen and documented in the nursing notes?

• Are the most up-to-date blood results available (especially the blood count and clotting studies)? Ideally, they should be displayed on a flow chart.

• Is there an informed member of the medical team (e.g. the endoscopist or the registrar) available on the ward?

• Are the case notes available and, most importantly, is the endoscopy record available?

• Does the patient understand why a surgeon has been involved?

• Has an ECG been performed and seen by the medical team?

▪ Following an established management protocol based on national guidelines

▪ Intensive nursing input during the initial period of instability

▪ Clear guidelines for the changes in observations to be reported to medical staff

▪ Combined medical and surgical input in high-risk patients

▪ Use of central venous lines in high-risk patients

▪ Good liaison with the gastroenterology team

▪ Access to early endoscopy and endoscopic haemostatic techniques

▪ Appropriate monitoring, including clotting studies in all high-risk patients

▪ Patients for emergency surgery to see the senior surgeon preoperatively

Answering Relatives’ Questions in Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

How serious is the bleeding? The answer depends on the patient. Although the average mortality risk from upper gastrointestinal bleeding is 10%, it varies by a factor of 20 between the young and the elderly, and from extremely low rates in acute gastritis to perhaps 20–30% in acute bleeding varices.

Will the ulcer stop bleeding of its own accord? Eight out of ten ulcers stop bleeding on their own; the rest are treated at endoscopy with injection or coagulation. In these cases nine out of ten will stop bleeding, but a very small number will need to go on to urgent surgery, either because the procedure does not work or because it is only temporarily successful.

How will the endoscope examination help? It will tell us the cause of the bleeding and will give some idea if it will stop. Heavy bleeding from an artery, for example, is more likely to need surgery than a superficial area of inflammation in the gullet. It may be necessary to try and seal off the bleeding at the time of the examination, using locally applied heat or an injection into the bleeding point.

What is the outlook in bleeding from oesophageal varices? Although treatments have improved greatly in recent years, this remains a very serious condition. Much will depend on whether the bleeding can be stopped and, if it can, whether there is further bleeding in the first 2–3 days. About a fifth of all patients who bleed from varices re-bleed in the first few days, and for them the outlook is not particularly good.

Important Questions to Ask the Patient or Relatives

• What is the patient’s alcohol intake?

• Is the patient on NSAIDs, low-dose aspirin, steroid tablets or warfarin?

• Is there a history of abnormal bruising or bleeding?

• Has there been previous surgery, and if so what was it?

• Has there been a problem with blood transfusions?

Reassessing the Patient on Return From Endoscopy

Patients will have been away from the ward for an hour or more undergoing endoscopy. Systematic nursing observations may have been curtailed during and after the procedure. Fluid balance charts and transfusion needs may not be correctly documented and the patient, who is already sick, has the aftereffects of the procedure and sedation to overcome. It is vital to reassess the patient on return to the ward.

• Is the airway secure (most patients will have been sedated for the endoscopy)?

• Is the patient in the recovery position while the sedation wears off?

• Is the patient oxygenated?

• Has resuscitation been adequate (pulse, blood pressure, CVP, capillary filling)?

▪ Ensure the safety of the patient

▪ Correct the oxygen saturation

▪ Secure the venous access

▪ Measure the pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate

▪ Identify the signs of shock – pallor, sweating, restlessness, confusion

▪ Ask about liver disease and clotting disorders

▪ Assess the likely severity of the initial blood loss and chart further loss

▪ Take an appropriate history

▪ Complete baseline observations

▪ Reassure the patient and attend to the patient’s basic comforts

▪ Follow the vital signs at appropriate intervals

▪ Ensure accurate fluid balance charts

▪ Report signs of re-bleeding/changes in the vital signs

▪ Save any important evidence (vomited blood, fresh melaena)

▪ Warn the patient about the likely need for an endoscopy

▪ Report any abdominal pain

▪ Initiate careful oral hygiene measures

• Are the management plans clear?

– What did endoscopy show (spurting/oozing arterial bleed, varices)?

– Are there prescriptions for fluids and blood?

• Are there any special requirements (octreotide, omeprazole infusion, platelets, FFP)?

• Can the patient eat and drink? Patients who remain stable 4h after endoscopy can usually drink and start a light diet

• Is the fluid balance chart accurate and is adequate blood available?

• Has there been liaison with the relatives?

At this point, the intensity of nursing input depends on whether the patient is in a high-risk category. A sick patient with heavy blood loss (more than 4 units of blood transfused in the first 12h) and with a high chance of re-bleeding will require continuous and close observation; a young patient with superficial gastritis and little evidence of bleeding will need much less intensive input.

Portal Hypertension and the Management of Oesophageal Varices

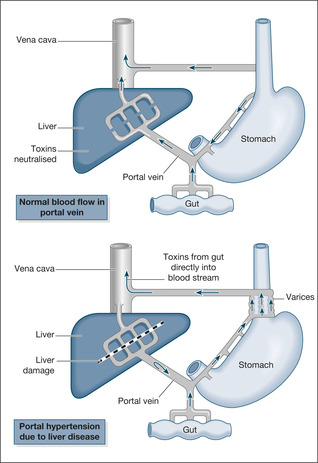

Nutrients, drugs and potential toxins are carried in the portal vein from their main site of absorption, the stomach and small intestine, to be processed and detoxified within the liver. To enable these substances to reach the liver cells, the portal vein divides into small capillaries (venules), which form a delicate network throughout the substance of the liver.

The branches of the portal vein are vulnerable to any disease process such as cirrhosis or severe hepatitis that causes structural damage within the liver – the venules become obliterated and the portal venous blood flow is obstructed. If the venous drainage from the upper intestine to the liver is obstructed, pressure builds up behind the blockage (portal hypertension; →Fig. 5.3) and the blood is forced into finding an alternative route. In this situation, veins at the lower end of the oesophagus, which drain into the inferior vena cava (part of the systemic venous system) and normally only carry small amounts of blood, become the main route of venous traffic from the upper gastrointestinal tract (portosystemic shunting). These veins have to enlarge and in doing so form oesophageal varices (Fig. 5.3).

There are two consequences of portosystemic shunting for the patient:

• substances absorbed from the gut bypass the liver and pour straight into the vena cava. The resulting accumulation of toxic dietary components, in particular ammonia, can lead to increasing confusion, drowsiness and ultimately coma – hepatic encephalopathy

• the varices enlarge progressively, and may rupture and bleed

The logical way to stop bleeding from oesophageal varices is either physically to obliterate the varices themselves or to reduce the pressure in the portal vein. Varices can be obliterated by injection sclerotherapy using an irritant inserted directly into the bleeding varices through an endoscope. A newer technique, which has proved more effective than injection, oesophageal banding, uses an endoscopic device to lasso the varices with small elastic bands. These techniques have largely replaced the use of direct oesophageal compression with an inflated balloon (the Sengstaken tube). Varices within the stomach respond best to injections of a biological glue – cyanoacrylate.

There are two important drugs, terlipressin and octreotide, which will stop variceal bleeding by lowering the portal pressure and reducing the flow of blood through the varices. Terlipressin, 1–2mg i.v. prior to endoscopic treatment and at four hours and at eight hours is the preferred initial treatment and will stop the bleeding in eight out of ten patients. In patients with known liver disease, terlipressin or octreotide is often given at the first sign of significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding, to be discontinued later if endoscopy does not confirm that the blood is coming from varices. Treatment is then continued with either terlipressin for 48 hours (2mg i.v. every four hours) or octreotide for five days (50mcg i.v. bolus then 50mcg per hour).

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) is a new radiological technique for reducing the portal pressure when other methods to stop the bleeding fail. The procedure, performed through a cannula inserted into the jugular vein, involves making a channel within the substance of the liver between the portal vein and the systemic veins – an artificial portosystemic shunt – which reduces the pressure in the portal vein (although the extra shunting may trigger or worsen hepatic encephalopathy).

Acute Liver Failure and Hepatic Encephalopathy

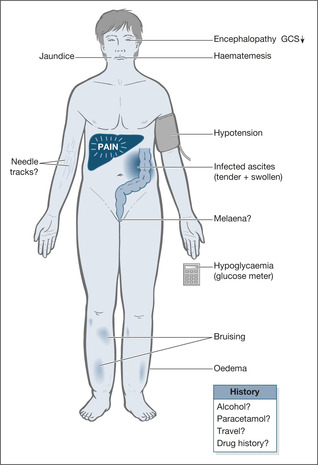

Two groups of patients present with acute liver failure: those in whom it is precipitated by an acute event such as viral hepatitis, and those in whom the episode occurs on a background of chronic (most commonly alcoholic) liver disease with portal hypertension. Acute liver failure has a number of components that make it a particularly challenging nursing problem (→Fig. 5.4).

|

| Fig. 5.4 |

Impairment of the consciousness level

The combination of poor liver function and portosystemic shunting means that toxic substances from the gut, in particular ammonia, are either dealt with ineffectively by the liver or bypass it altogether. The result is a toxic encephalopathy with impairment of the consciousness level that can progress rapidly from confusion and agitation to deep coma. When it does, the patient has usually developed cerebral oedema and requires intensive care, preferably in a specialist liver unit. It is useful to assess and follow changes in the hepatic encephalopathy using a standard scoring system (→Box 5.2).

Box 5.2

| 0 | normal |

| 1 | mood change |

| 2 | drowsy |

| 3 | confused/disorientated |

| 4 | coma/unrousable |

Bleeding varices and clotting abnormalities

Patients in acute liver failure are at great risk from upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to the combination of varices and impaired clotting. Not only will this cause cardiovascular instability, but blood in the gut provides a source of toxins that can worsen hepatic encephalopathy.

Metabolic abnormalities

The main problems are hypoglycaemia and renal failure. Hypoglycaemia is important because it will contribute to confusion and can be readily corrected. Patients in liver failure who develop renal failure do particularly badly. At presentation, these patients are often hypovolaemic: careful early fluid replacement (monitored with a CVP line) can improve their renal function. Hypotension unresponsive to fluid replacement will require inotropic support and possibly corticosteroids.

Management of Acute Liver Failure in the First 24H

Patients with acute liver failure need supportive care until there is either spontaneous improvement or they are transferred to a specialist unit with a view to more intensive treatment; this may include, as a last resort, transplantation.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is managed according to its severity and its mode of onset. Acute liver failure with grade 3 or grade 4 encephalopathy (confusion or coma) is usually associated with cerebral oedema. The patient needs to be sedated, paralysed and ventilated, as agitation and restlessness increase intracranial pressure. Intravenous mannitol (0.5mg/kg) can be used in the emergency situation to reduce cerebral oedema. Acute on chronic liver failure with encephalopathy (such as may occur in decompensating alcoholic liver disease) can be treated less aggressively: the intake of protein, the main source of ammonia, is reduced and the bowel is cleared using lactulose, which reduces production of ammonia in the bowel and also empties it through its action as a laxative. The dose of lactulose is adjusted until there are between two and four soft stools per day. Oral neomycin, which sterilises the bowel of all ammonia-producing gut bacteria, can also be used.

Bleeding

Bleeding can be minimised by correction of any clotting abnormality. The safest way to monitor bleeding and fluid replacement in the unstable phase is to use a central venous pressure line. There is a fine line between underand over-transfusion in these patients, with the constant risk of pulmonary oedema (particularly when saline is infused) to be balanced against the deleterious effects of under-transfusion on kidney function.

Metabolic problems

Hypoglycaemia must be avoided by hourly checks on the BM stix and the appropriate use of i.v. 10% or 20% dextrose. Patients with acute on chronic liver disease have often been on diuretics for ascites and may have acutely low potassium levels that need to be corrected. Patients with acute liver failure are ‘hypermetabolic’ – burning up calories and protein – so nasogastric feeding must be considered early. If there is an excessive gastric aspirate it can be reduced using maxalon and clarithromycin (acting as pro-kinetic drugs to aid gastric emptying).

Critical nursing tasks in acute liver failure

Ensure the safety of the patient: ABCDE

The airway is at risk in grade 4 encephalopathy, although most patients with acute liver failure will be confused and restless rather than comatose. Oxygen is administered and oxygen saturations are monitored. A baseline respiratory rate is required, because hypoxia and an increase in respiratory rate are early signs of pulmonary oedema, but could also indicate aspiration pneumonia. The pulse and blood pressure are critical for assessing blood loss and septicaemic shock – septicaemia from gut organisms often gives a picture of hypotension, fever and warm vasodilated extremities. Measure the BM stix urgently: hypoglycaemia is the one important cause of reversible neurological disturbance. The patient should be rapidly assessed for signs of gastrointestinal bleeding (nature of the stool, evidence of haematemesis).

▪ Ensure the safety of the patient:ABCDE

▪ Gain venous access

▪ Carry out top-to-toe examination

▪ Liaise with the patient’s family

▪ Ascertain the possible causes of liver failure

▪ Explain the likely interventions in the first 48h

▪ Obtain a drug history

Carry out top-to-toe examination

Examine for signs of sepsis, infected needle tracks (hepatitis) and tender abdominal distension (infected ascites?).

Liaise with the patient’s family

It may not be possible to obtain the necessary details from the patient. It is critical to try and obtain some form of psychosocial history. If emergency transplantation becomes an issue, a major determinant of likely success is the patient’s pre-existing psychological status.

Ascertain the possible causes of acute liver failure

The most common causes of acute liver failure are paracetamol poisoning and acute hepatitis. It is critical to exclude the possibility of a paracetamol overdose: by the time the patient presents with liver failure the drug may be undetectable in the blood, and yet specific intervention with the antidote, N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®), can be life-saving even at this late stage. The various forms of hepatitis can be suspected from the history: recent travel, i.v. drug abuse, transfusions, drug history. Include recreational drugs (ecstasy) and over the counter medications (health food preparations). Acute on chronic liver failure is most commonly seen in alcoholic liver disease, but other causes include various forms of non-alcohol-related cirrhosis such as primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune liver disease.

Explain the likely interventions in the first 48h

• Endoscopy – this will be done urgently if there is active bleeding

• Radiology – possible interventions to control bleeding

• Transfusions – blood products and clotting factors may be necessary

• Multiple infusion lines – central and peripheral infusions, urinary catheter to monitor output

• Transfer – some patients with acute severe liver disease may need intensive care, either locally or at a regional liver unit. The patient will need to be stabilised before transfer can be considered or safely undertaken

Obtain a drug history

It is vital to obtain an accurate drug history. Some drugs are directly toxic to the liver (anti-TB drugs are notoriously hepatotoxic) or may have important side-effects – hypokalaemia associated with diuretic use is a common problem in liver disease. Non-steroidal drugs increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and also increase the likelihood of problems with kidney function. Intravenous drug abuse increases the risk of both acute and chronic hepatitis.

Important nursing tasks in acute liver failure

Determine accurate fluid balance

Fluid balance in acute liver failure is complex, but its management is made easier if there are accurate input and output charts. Several infusions can be running simultaneously: dextrose, N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®), clotting factors and central lines. Vomit and any bowel action must be strictly documented. Hourly urine output measurements are critical to the assessment of kidney function: an output of less than 30ml/h is a cause for concern.

Identify sepsis

Primary bacterial peritonitis – infection of the patient’s ascitic fluid – is a common problem in liver failure and can be difficult to diagnose. Patients with peritonitis may complain of generalised abdominal pain, associated with tenderness and discomfort when they are moved around the bed. There may be a fever. Chronic liver disease, especially in malnourished alcoholic patients, is often associated with skin sepsis, as infected abrasions, skin abscesses or infected pressure sores. The mouth is also an important focus of infection.

Reassure the patient and manage confusion and disorientation

Patients with acute liver disease are often distressed and agitated. There may be hepatic encephalopathy and some may be suffering from alcohol withdrawal. Sedation has a limited role to play, unless the patient is a danger to himself, as it can worsen liver failure. In the less confused patient, simple measures such as nursing the patient in a well-lit room, constant reassurance and explanation and bringing in close relatives are often sufficient. In severe encephalopathy, however, sedation and ventilation may be the only option in the face of worsening cerebral oedema. It is important to exclude a reversible cause for the restlessness, such as hypoxia, hypoglycaemia, pyrexia or acute urinary retention. Venous access is often difficult, so infusion sites should be well protected.

Carry out general nursing measures

The safety of these acutely ill patients is at risk. Pressure areas and the skin in general are often poorly nourished and in poor condition. Oral hygiene is usually poor and needs careful attention. Restless patients will need close observation, which may have to incorporate safety measures such as cot sides.

Example Cases in Acute Liver Failure and Hepatic Encephalopathy

Case Studies 5.4 and 5.5 give examples of management of cases of acute liver failure.

Case Study 5.4

A 34-year-old woman was admitted to hospital with a 4-week history of abdominal swelling and a 3-day history of increasing jaundice.There had been a general deterioration in her health, with lethargy and anorexia. For the past 2 weeks she had been taking regular paracetamol for a constant headache, but she denied taking an overdose.

She had been a heavy drinker since the age of 16 years, predominantly cider – between six and ten cans every day. She had been tremulous in the morning for some time and was spending all her money on alcohol. She was unable to remember a day when she had not had a drink. She was married, with a 4-year-old son and smoked 25 cigarettes per day.

On admission the patient was jaundiced and smelt of alcohol.The patient was agitated but not confused or drowsy and there was a fine tremor.The BM stix reading was 6mmol/L.Temperature was normal, pulse 110 beats/min and blood pressure 130/70mmHg, with no postural drop. Her abdomen was distended but not tender but both her liver and spleen were enlarged.There was no melaena on rectal examination.

The working diagnosis was acute alcohol-induced liver damage, possibly associated with an additional insult from excess paracetamol ingestion.

Bloods were taken for:

• liver function tests

• clotting studies

• haemoglobin (to exclude bleeding),WCC (to exclude infection) and platelets (low in alcoholics)

• blood sugar

• kidney function (the kidneys are very vulnerable in liver disease)

• alcohol level

• paracetamol level (to exclude acute paracetamol toxicity)

• culture (infection can trigger off liver failure if there is pre-existing liver disease)

Ascitic fluid was tapped and cultured.

Important initial questions

• Why is she agitated?

— hypoglycaemia?

— alcohol intoxication?

— alcohol withdrawal?

— early hepatic failure (encephalopathy)?

• sepsis?

• Is there any gastrointestinal bleeding (i.e. bleeding varices)?

Initial and subsequent investigations

The results of the investigations are shown in Table 5.2. Paracetamol levels were negative and alcohol levels were three times the legal driving limit.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 313 | 393 | 396 |

| AST (I.U./L) | 623 | 1477 | 1282 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 33 | 28 | 26 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 132 | 121 | 124 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 3.8 | 6.7 | 12.3 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 45 | 87 | 148 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 17 | 24 | 20 |

Progress

Half-hourly observations including BM stix were started. Four hours after admission, she became more drowsy and her BM stix fell to 4.5mmol/L. Intravenous glucose 20% was started.After some discussion, she was given 10mg vitamin K i.v.

The patient was observed overnight and by the next day she was confused and increasingly restless in spite of normal blood sugars. Her liver function had deteriorated and she had developed a flapping tremor.

At this stage the differential diagnosis was between alcohol withdrawal and hepatic failure with encephalopathy.The liver function test results had deteriorated and the high liver enzyme findings suggested acute alcoholinduced liver damage: alcoholic hepatitis.There was neither evidence of acute infection nor active upper gastrointestinal bleeding, both of which could have triggered liver failure in a patient with underlying liver disease.

Over the next 48h, the patient’s increasing confusion became difficult to manage and so she was cautiously given oral Heminevrin®. Her renal function was noted to be deteriorating and her urine output had fallen to less than 20ml/h. After discussion with the Liver Unit she was started on oral prednisolone (a treatment for alcoholic hepatitis).Twenty-four hours later, as her confusion had increased, she was transferred with a view to assessment and possible liver transplantation.

Case Study 5.5

A retired 55-year-old man was admitted to hospital, having collapsed at home after passing a large amount of black stool. According to his wife, he had been unwell for 3 weeks since returning from a holiday in Spain: a graze on his leg had become infected, he had developed swelling of both ankles and his motions had been very dark for a week. He had been drinking heavily for around 10 years to cope with business worries, and on the recent holiday had consumed between five and ten pints of beer daily. He had previously been told that he was suffering from alcoholic cirrhosis.

On admission, he was drowsy but rousable and responding appropriately: GCS = 14 (E3M6 V5). His BM stix result was 8.5mmol/L. His pulse was 120 beats/min and his blood pressure was 105/80mmHg lying and 90/60mmHg sitting up. He was apyrexial. Oxygen saturations were 94%. Capillary filling was normal. He was obviously jaundiced and had gross abdominal distension, with tense oedema of both ankles.There was an infected skin abrasion on his right calf and scattered bruising.While being admitted, he used a bedpan and passed 400ml of black stool containing fresh clots. This man had the features of advanced (decompensated) liver disease.These are:

• failure of the liver to manufacture enough albumin – ascites and oedema, and low serum albumin

• failure of the liver to excrete bilirubin – jaundice and a high bilirubin level

• failure of the liver to manufacture enough clotting products – bruising or bleeding.The liver is the main source of several important clotting factors and if, as a result of liver damage, these fall to a third or less of their normal levels, the patient will be at risk from bleeding.This results in spontaneous bruising and, more importantly, an impaired clotting response to any gastrointestinal bleeding. Vitamin K, which is needed to activate these factors, may also be in short supply because, as one of the fat-soluble vitamins, it needs normally functioning bile for it to be absorbed from the diet.The prothrombin time tests these vital aspects of liver function: it should not normally exceed 11–13s

• failure of the liver to destroy toxic products – a major function of the liver is to break down the body’s toxic products. In liver failure the accumulation of toxins, in particular ammonia, leads to increasing drowsiness, confusion and ultimately coma – so-called hepatic encephalopathy

• upper gastrointestinal bleeding – the main worry in this man’s case is that he is bleeding from oesophageal varices, a common and potentially fatal complication of severe liver disease. Because of their lifestyle, patients with alcoholic liver disease are also prone to peptic ulcer disease: the management of a bleeding ulcer is so fundamentally different from that of bleeding varices that the exact source of the haemorrhage has to be identified as soon as possible

Ensuring the safety of the patient: ABCDE

The consciousness level of the patient was impaired, but with a GCS above 8 the airway is not at risk. However, an abnormal GCS must always be monitored. In acute liver failure, for example, the GCS can fall abruptly due to complications: worsening encephalopathy and, in particular, the sudden development of cerebral oedema.The BM stix result of 8.5mmol/L excluded hypoglycaemia (a complication of liver failure) as the cause for the altered consciousness level.

The circulatory changes suggest significant blood loss: tachycardia and postural hypotension supported by the appearance of fresh melaena. Recognisable fresh blood in a melaena stool is a sign of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding.The patient will need initial resuscitation with i.v. fluids and blood, close serial observation of the pulse, blood pressure and urine output will be critical, blood loss will have to be documented and central venous cannulation will be required.

Exposing the patient revealed the infected skin abrasion on the lower limb. Any infection in this critically ill man is potentially important; the wound should be carefully documented and swabbed.

Reassurance and explanation

The initial assessment indicates that the patient should be forewarned and reassured about the intense activity that will take place in the next day or so. Losing blood from internal bleeding is a frightening experience, and initially the patient will be very distressed and will feel out of control. Although pain is not usually a problem, there is likely to be intense thirst (blood loss), nausea and perhaps vomiting.

The patient’s subsequent progress

The patient was given oxygen via a high-flow mask. Large-bore cannulae were sited in both arms and i.v. Haemaccel® was given – 1 unit over 30min – while awaiting blood for transfusion.The transfusion technician, the laboratory and the endoscopy unit were alerted to the potential severity of the problem.

The initial blood tests confirmed marked anaemia (haemoglobin 6.0g/dl), moderately deranged clotting and grossly abnormal liver function tests.

Within the first hour, the following procedures were completed:

• cardiac monitor

• central line (internal jugular approach)

• urinary catheter (to monitor the exact urine output)

• ascitic tap (to exclude infection in the ascitic fluid as the cause of the deterioration)

The initial phase of treatment involved:

• careful transfusion aiming to maintain a CVP of +5cmH2O – patients with liver failure handle excess fluid, particularly saline, badly. However, there is a risk of kidney failure if adequate fluids are not given at an early stage. Despite a careful approach, a subsequent chest film on the patient showed pulmonary oedema

• i.v. antibiotics: cefuroxime and metronidazole – these are administered on the basis of an assumption that infection is already present, or very likely to occur, as a complication.This combination was chosen as most effective against gut organisms that may infect the ascitic fluid or biliary tree

One hour after admission, the patient had received 2 units of blood, 3 units of FFP and 1 unit of Haemaccel®. His CVP had risen to +19cmH2O and his chest film (to show the central line) showed pulmonary oedema.

Emergency endoscopy, after treatment of the pulmonary oedema, showed confluent oesophagitis and fresh bleeding from an oesophageal varix.The varix was injected with a sclerosant (ethanolamine oleate) and as this appeared to control the bleeding the patient was returned to the ward and started on an octreotide infusion at 50 μg/h.

His observations did not stabilise;his pulse remained high at 115–120 beats/min, his systolic blood pressure stayed below 95mmHg and 6h after admission his CVP dropped to +2cmH2O and he had a large fresh haematemesis. Repeat endoscopy confirmed further active variceal bleeding and the injections were repeated.

He returned to the ward and overnight his pulse, blood pressure and CVP stabilised with further blood transfusions and FFP. Hourly urine outputs however had dwindled to 10–20ml/h and the patient was difficult to rouse.

His blood results showed worsening kidney function. At mid-morning he had a further very large haematemesis associated with worsening confusion. A Sengstaken balloon was passed as an emergency procedure and he was transferred to the ITU.

At this stage the problems were:

• uncontrolled variceal bleeding

• worsening hepatic failure

• pulmonary oedema

• hepatorenal syndrome (kidney and liver failure in a critically ill patient)

The outlook in this situation is extremely poor.

Acute Jaundice

Jaundice is caused by a build-up of the yellow pigment, bilirubin, a breakdown product of haemoglobin and related proteins, which is normally produced and excreted by the liver. Virtually all cases of jaundice on the Acute Medical Unit will be due either to acute liver damage from viral hepatitis (→Case Study 5.6) and toxins (usually alcohol) or to obstruction of the bile ducts by gallstones or, less commonly, tumour.

Case Study 5.6

This man was admitted with a 2-week history of vomiting after meals and a 1-week history of increasing jaundice, dark urine and pale stools.There was no history of pain, gallstones or risk factors for hepatitis (transfusions, travel or at-risk behaviour). He was on no medication and was a light social drinker.

On examination he was fully alert, markedly jaundiced and had a slightly enlarged and tender liver.There were no signs of chronic liver disease.

Blood tests were available from 4 days before and from the day of admission. His bilirubin level had doubled over 4 days but his liver enzymes were falling from markedly high levels (AST from 2800 to 590IU/L).The albumin and clotting studies (which are the two most important tests of how well the liver cells are working) were normal.

A liver scan showed no abnormality in the liver, no signs of obstruction to the biliary tree and a normal pancreas. A day after admission the tests for glandular fever came back positive. A diagnosis of viral hepatitis due to glandular fever was made.

Acute hepatitis presents with flu-like symptoms, joint pains, nausea and discomfort in the right upper abdomen. Most of the symptoms improve with the sudden appearance of jaundice, although the nausea and vomiting may increase. Occasional cases progress to acute liver failure, but for the majority treatment with rest, a light, low-fat diet and alcohol avoidance will lead to a full recovery. Half of the cases of infective hepatitis are due to hepatitis A. This is transmitted by the orofaecal route, but spread to close domestic contacts can be prevented by vaccination. Hepatitis B is less common and tends to be associated with transmission through bodily fluids: transfusion, infected needles and other high-risk behaviour. Close contacts such as sexual partners also require protective vaccination.

Gallstones, acute cholecystitis and ascending cholangitis

Gallstones usually present with biliary colic – severe upper abdominal pain going through into the back. If they become wedged in the bile ducts there is a risk of infection, either confined to the gall bladder (acute cholecystitis), or spreading up the bile ducts to the liver (ascending cholangitis; →Case Study 5.7). In these situations there is pain, but also signs of sepsis (fever, high white cell count) and, with spreading infection, abnormal liver function tests. Nursing management is focused on assessing the patient’s progress and ensuring that while investigations are in progress there is adequate pain relief. An overall deterioration, continuing or worsening pain and fever that fails to respond to i.v. antibiotics indicate a need for intervention, either by endoscopic attempts to remove the impacted stones (ERCP with sphincterotomy) or a direct surgical approach.

Case Study 5.7

A 75-year-old man was admitted with the sudden onset of prolonged shivering episodes lasting 15min at a time.This was followed after about 4h by an attack of retrosternal chest pain associated with nausea.There was a past history of peptic ulcer disease and chronic atrial fibrillation.

On examination he was mildly jaundiced and sweating profusely. His pulse was 85 beats/min in atrial fibrillation and blood pressure normal; the temperature was 38°C. His liver was mildly enlarged and he was tender over the gall bladder.

The liver function tests were abnormal, with a high bilirubin and moderate elevation of the AST (79IU/L) and alkaline phosphatase (325IU/L). An urgent ultrasound showed gallstones and a dilated biliary tree.

A diagnosis of infection in the biliary system spreading to the liver (ascending cholangitis) was made and the patient started on i.v. fluids, ampicillin and gentamicin.

Acute Abdominal Pain

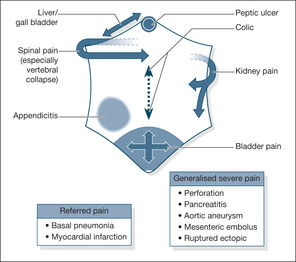

Abdominal pain is a common complaint on the acute medical ward. Although it is a feature of several medical conditions such as cardiac failure (liver congestion) and acute gastritis, it can also be due to a ‘pure’ surgical condition such as acute appendicitis or intestinal obstruction in a patient who has been admitted for medical reasons because the diagnosis was not immediately apparent (→Fig. 5.5).

Critical nursing tasks in acute abdominal pain

Establish the site and pattern of the pain

Midline localised pain is likely to arise from the stomach, duodenum or bowel. Severe pain that radiates into the back suggests either acute pancreatitis (→Case Study 5.8), a deep peptic ulcer or an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Right-sided pain may arise from the liver, gall bladder or appendix. Kidney pain starts in the loins and radiates to the front or into the groin. An intra-abdominal catastrophe such as a perforation or a sudden blockage of the blood supply to part of the gut causes severe acute generalized pain from the outset. Pain that waxes and wanes (colic) occurs in acute gastroenteritis but is also seen in obstruction, in which case the pain becomes progressively more severe. If obstruction is suspected, look for evidence of a strangulated hernia – a tender swelling in the groin.

Case Study 5.8

A 56-year-old woman was admitted with a 6-month history of intermittent abdominal pains and a 3-week history of jaundice with pale stools.The pain was situated below the rib cage on the right and would be constant for an hour or so before easing off. On the day of admission, the pain was much more severe and prolonged. It also radiated into the back and was associated with vomiting.

On examination she was in pain, mildly jaundiced and looked unwell.There was a low-grade fever, a pulse of 110 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min and a blood pressure of 110/60mmHg, with no postural drop. Oxygen saturation was 92%.

She was tender over the gall bladder and there were only scanty bowel sounds.

The abnormal blood tests were as follows:

WCC 16.5 × 109/L, bilirubin 59 μmol/L, AST 182IU/L, amylase 5727 IU/L

An urgent abdominal ultrasound showed gallstones and a dilated biliary system.

A diagnosis of gallstone-related pancreatitis was made.The patient was transferred to the surgeons for further management.

Assess the severity of the pain

Patients with severe abdominal pain are often grey, restless and clammy, and may be either lying still not wanting to be moved (acute peritonitis) or doubled up by intestinal colic. Oesophageal and peptic ulcer pain are not usually severe unless there are complications such as perforation (→Case Study 5.9). Gall bladder pain is generally very severe (→Case Study 5.10), as is the pain of acute pancreatitis.

Case Study 5.9

A 28-year-old man was admitted with 6h of epigastric pain. He gave a long story of similar, less severe pain occurring an hour or so after food or alcohol and relieved by indigestion tablets. He looked well, but had marked epigastric tenderness.

Case Study 5.10

A 40-year-old woman was admitted with severe constant pain under the right rib margin that radiated into the back. She was restless and in pain, with marked tenderness over the gall bladder area.There was a trace of bile in her urine and she appeared mildly jaundiced. Over the next 24h she developed nausea, vomiting and a fever and was started on i.v. antibiotics for a diagnosis of presumed acute cholecystitis.

Look for signs of shock

Severe abdominal pain with signs of shock – tachycardia, hypotension and increased respiratory rate – suggests a serious intra-abdominal catastrophe: perforation, acute bowel ischaemia, ruptured aneurysm or acute pancreatitis. A rising pulse rate, increasing pain, falling blood pressure and decreasing hourly urine output suggest an impending intra-abdominal disaster. These patients require urgent resuscitation and medical evaluation, including abdominal films and an immediate surgical opinion.

Examine for abdominal rigidity and peritonitis

The most obvious features of acute peritonitis are localised pain on coughing and board-like abdominal rigidity, accompanied by few, if any, bowel sounds. The patient does not want to move, appears shocked and is usually vomiting. If the condition has been developing over several days, the signs may be less dramatic: abdominal distension, vague tenderness, but a silent abdomen. Common causes of peritonitis are perforation of a peptic ulcer or acute appendicitis. Acute peritonitis may be accompanied by signs of sepsis – hypotension, rapid thready pulse and cold, mottled extremities.

Prepare for resuscitation

Patients with an acute abdomen, particularly peritonitis, need urgent resuscitation, often in preparation for surgery. The basic requirements are oxygen, i.v. fluids, nasogastric intubation and urinary catheterisation to ensure an adequate urine output. Once a provisional diagnosis and management plan is in place, the patient must be given adequate analgesia, which may require i.v. opiates.

Important nursing tasks in acute abdominal pain

Look at associated clinical features

A review of the reasons for the admission is helpful in evaluating the nature of the pain. Right upper abdominal pain in a patient with heart failure may be due to liver congestion. Pain with jaundice may be due to gallstones. Severe pain developing in a patient with a bleeding ulcer may be due to perforation. Acute pancreatitis is common in alcoholics, but can also complicate gallstones and DKA.

Review the previous history

Review any similar previous pain, particularly if it has been investigated already. Some drugs are commonly associated with upper gastrointestinal ulcers and erosions: NSAIDs, aspirin and steroids. Old notes are needed urgently, with a particular view to the previous surgical history (→Case Study 5.11).

Case Study 5.11

A 60-year-old man was admitted with a 4-day history of severe intermittent pain in the right loin, radiating around into his abdomen. For the past 12h he had a number of sudden ‘chills’ and had mild urinary frequency. In the past, his left kidney had been removed because of ‘infection’. An urgent ultrasound showed a large renal stone wedged in the right ureter and an enlarged and obstructed right kidney. Blood cultures were positive for Escherichia coli.

Review the urine test results

Urinary infection is one of the most common causes of abdominal symptoms, either suprapubic discomfort from bladder distension or loin pain from the kidneys. Inspect a urine sample – if it is cloudy and strong-smelling, infection is likely. Send a pregnancy test in a female of child bearing age.

Review the stool chart

The nature of the patient’s bowel actions is of fundamental importance in assessing the cause of abdominal pain. Obstruction is associated with absolute constipation: no motions and no flatus. Colic with diarrhoea suggests colitis, particularly if there is blood in the stool, or gastroenteritis.

It is important to document the exact type of stools that are passed. If the problem includes diarrhoea, the volume and quality of the stool is vital in assessing the fluid replacement needs of the patient. Bloody diarrhoea is a serious problem that has relatively few causes: severe colitis, campylobacter enteritis and, in the elderly, acute ischaemic colitis. Fresh stool specimens must be sent (and processed by the laboratory) urgently.

Prepare the patient for further investigations

Basic blood tests are done on admission to assess the degree of shock (renal function) and to look for evidence of infection (white cell count and blood cultures). It is vital to obtain an up-to-date ECG to help identify the at-risk cardiac patient. Abdominal and chest films identify perforation; abdominal ultrasound and CT can look for other causes such as gallstones, pancreatitis, intra-abdominal abscesses (→Case Studies 5.12) and abdominal aneurysm.

Case Study 5.12

CASE 1

Two weeks after a myocardial infarction, an 80-year-old woman was admitted to hospital, severely ill with hypotension, tachycardia and acute generalised abdominal pain. Her abdomen was diffusely tender with very few bowel sounds. She remained critically ill despite fluids and antibiotics, and underwent emergency laparotomy.The findings were of a gangrenous intestine due to an embolus lodged in the mesenteric artery.The embolus had arisen from the scar at the site of her myocardial infarction.

CASE 2

A 60-year-old woman awoke with constant midline upper abdominal pain. During the day, the pain persisted and became more severe.The general practitioner visited and diagnosed constipation. By the evening she was confined to bed with generalised, constant abdominal pain; she had started to shiver and was unable to get warm. On admission to hospital, she was in shock and had marked generalised abdominal tenderness. She was resuscitated with oxygen and i.v. fluids and transferred to the surgeons. At operation she had a ruptured diverticular abscess of the large bowel, with faecal peritonitis.

Acute Diarrhoea: Sources and Courses

Infective Diarrhoea

There are six common causes of infective diarrhoea:

• Campylobacter

• Salmonella

• Escherichia coli

• Clostridium difficile (due to antibiotics, particularly oral cephalosporins)

• SRSV (Small Round Structured Virus or Norovirus)

• rotavirus

The main features are listed in Table 5.3.

| Organism | Food | Incubation | Main clinical features | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter | + | 5 days | Bloody diarrhoea | Acute colitis |

| Salmonella | + | 2 days | Vomiting and diarrhoea | Shock |

| E. coli (0157:H7) | + | 2 days | Cramps and diarrhoea | HUS |

| Clostridium difficile | – | 10 days | Acute severe colitis | Acute colitis |

| SRSV | – | 1 day | Nausea and vomiting | Outbreak |

| Rotavirus | – | 1 day | Diarrhoea and vomiting | Outbreak |

Patients are usually admitted to hospital with diarrhoea because of the worries about them maintaining their fluid intake against loss from both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract. The secondary problem involves distinguishing between acute infective diarrhoea and the acute inflammatory bowel diseases – ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Assessment

• History of recent foreign travel

• Ask about other possible cases

• Have there been recent doubtful meals/mass catering, etc.?

• History of recent antibiotic therapy

Is this patient at special risk?

Is there a history of recurrent diarrhoea?

A background of recurrent diarrhoea, especially associated with blood and mucus, makes an acute episode of diarrhoea more likely to be due to inflammatory bowel disease than to infection.

Nursing assessment in acute diarrhoea

At all times the nurse should ensure the safety of the patient: ABCDE.

Assess fluid loss

• How much is being passed and for how long?

• What has the fluid intake been?

• What have the urine volumes been (approximately)?

Look for evidence of shock

• Confusion/drowsiness

• Hypotension

• Oliguria (less than 30ml/h)

• Evidence of sepsis/fever

• If antibiotic-induced, has the original infection resolved?

Diagnosis

Infective diarrhoea is diagnosed from stool cultures, which must be obtained as soon as the patient is admitted to hospital. The organisms are easy to culture and in the case of Clostridium difficile the toxin can be identified in the stool.

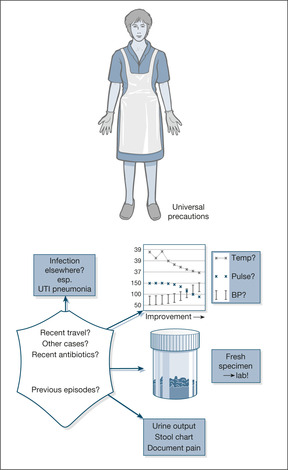

Nursing management in acute diarrhoea (Fig. 5.6)

To protect staff and patients, infection control must always be instituted in cases of acute diarrhoea until stool cultures are available. Most cases are selflimiting, provided that attention is paid to correct fluid balance. This is particularly the case with the viral diarrhoeas: SRSV and rotavirus. Patients who are most at risk are the elderly and frail. The principle of treatment is to correct fluid deficit and keep up with the loss of fluid in the stool and vomit (→Case Study 5.13). It follows therefore that the fluid balance and stool charts must be accurate. By its nature, diarrhoea will impair the accurate collection and measurement of urine, but the combined volume of stool and urine in a commode or bedpan can be estimated relatively easily. It is critical to keep a reliable stool chart.

|

| Fig. 5.6 |

Case Study 5.13

Twenty-four hours after a family celebration, a 75-year-old woman developed nausea, short-lived vomiting and acute diarrhoea that persisted for 4 days, culminating in an emergency admission. By this time, she was too weak to stand and complained of persistent mid-abdominal cramps.

Initial nursing assessment

ABCDE. The patient was conscious and orientated, complaining of severe thirst and generalised episodic abdominal pains.The respiratory rate was 25 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 90%, pulse rate 120 beats/min and a lying blood pressure of 90/70mmHg, decreasing to 70/40mmHg on sitting upright. The temperature was raised, at 38.5°C, and the BM stix was normal at 6.0mmol/L in spite of 4 days of virtual starvation.There were early pressure sores over the buttocks, perianal faecal soiling and mild bilateral ankle oedema. The patient’s abdomen seemed soft but generally tender, with very active bowel sounds.

History. There was no previous history of diarrhoea, recent antibiotic treatment or other significant illnesses. Several other guests at the function had also developed diarrhoea.There had been around eight bowel actions in the past 24h, but only two or three small amounts of urine had been passed over the previous 4 days.

Immediate management

• The assessment was of an elderly unwell woman with infective diarrhoea and dehydration, with a marked reduction in urine output, raising the possibility of renal failure.The elevated temperature suggested possible sepsis from the gut, or perhaps a urinary infection

• Oxygen was administered to bring the saturation to 95%

• Peripheral venous access was not possible and so a central cannula was immediately inserted

• A urinary catheter was passed to measure an accurate output

• Rehydration was started, with a combination of isotonic saline and potassium chloride supplements

• Bloods were taken for FBC,biochemistry and culture. An urgent stool specimen was sent directly to the on-call bacteriology technician.The consultant microbiologist was warned of the possibility of a food poisoning outbreak

• Abdominal X-rays were taken in view of the persistent pain, to exclude complications – severe colitis of any cause can lead to distension and, ultimately, perforation of the large bowel (‘toxic dilatation’)

Progress

The initial tests confirmed dehydration and renal failure (urea 54.1mmol/L, creatinine 504μmol/L); the sodium and potassium levels were low due to loss of electrolyte in the stool. Oral rehydration was not possible because of nausea and vomiting. Correction of the CVP from −3 to +5cmH2O over the first 4h with i.v. saline brought up the blood pressure. Urine outputs over the first 3 days of admission were 450ml, 800ml and 1500ml, indicating a return of renal function (this was ‘prerenal’ rather than established renal failure, as it responded promptly to fluid replacement). After discussion with the consultant microbiologist, the antibiotic ciprofloxacin was administered.

Salmonella enteriditis were isolated from the initial stool specimen and, as usually happens with this infection, the abdominal pain and diarrhoea settled over the first 7–10 days of admission.

Antibiotics are rarely needed unless there are signs of complications:

• persistent fever with a failure to improve

• development of severe colitis

• development of shock

• signs of infection elsewhere, e.g. infected heart valve

• severe colitis with the risk of haemorrhage, toxic dilatation and perforation

• HUS (Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome)

Ciprofloxacin is the drug of choice except for C. difficile, for which treatment is usually oral vancomycin or metronidazole.

Clostridium Difficile Diarrhoea

The indiscriminate use of antibiotics has led to a large rise in bowel infections due to clostridium difficile. The clinical picture varies from mild diarrhoea to severe colitis with fever, systemic sepsis and death. Certain patients are at a particular risk

• Age over 65, particularly from nursing or residential homes

• Antibiotics (amoxicillin, co-amoxiclav, erythromycin, cephalosporins) within the past month

• Immunocompromised

• Previous C. Diff diarrhoea (25% of cases relapse or become re-infected)

• Patients on PPIs (omeprazole, lanzoprazole)