7.12 Gastroenteritis

Introduction

Acute gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. It is one of the commonest reasons for children to present to an emergency department (ED). Most children under 5 years of age have experienced an episode of gastroenteritis and most can be successfully managed without admission to hospital. Worldwide, however, gastroenteritis still remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.1

Aetiology

Gastroenteritis is caused by a wide range of pathogens including viruses, bacteria and parasites (as shown in Table 7.12.1). In developed countries, the majority of episodes are due to viruses, with rotavirus being by far the most common pathogen. The most common bacterial causes are Salmonella and Campylobacter. Shigella, Yersinia and Escherichia coli are less common, while Vibrio cholerae is seen in developing countries. Parasites such as Giardia and Cryptosporidium are sometimes the infective agent.

In general a bacterium is more likely to be the causative agent if:

Examination

The aim of the clinical examination is to exclude signs of an alternative cause of the symptoms, other than gastroenteritis (see Chapter 7.8) and to assess the degree of dehydration.

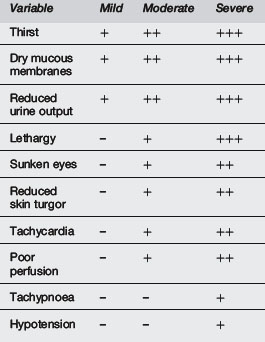

Assessment of dehydration

The accurate assessment of dehydration is difficult. Studies have shown that medical personnel tend to overestimate the degree of dehydration.2 The gold standard in assessment of dehydration is a loss of weight compared with a recent pre-illness weight. For example, a 1-year-old weighing 10 kg a week ago who presents with gastroenteritis for 3 days and now weighs 9.5 kg, is approximately 5% dehydrated. However, a recent weight is rarely available in the ED. Therefore, tables such as Table 7.12.2 use a combination of clinical symptoms and signs to estimate the degree of dehydration.

Various studies have attempted to validate combinations of these signs and symptoms with varying degrees of standardisation and scientific validity.2–5 Difficulties arise as some of the signs are subjective and gold standards differ.

Gorelick et al5 performed a good study in Philadelphia in 1997, which looked at the 10 clinical signs shown in Table 7.12.3. Using a gold standard of serial weight gain, they found that <3 signs correlated with <5% dehydration, 3–6 signs correlated with 5–9% dehydration and >7 signs correlated with >10% dehydration.

Source: Gorelick et al5

Laboratory investigations in the assessment of dehydration

There are few data to support the usefulness of laboratory tests in the assessment of dehydration due to gastroenteritis. Dehydration is thought to typically cause a metabolic acidosis. It is true that vomiting can cause a metabolic acidosis by several mechanisms including volume depletion, lactic acidosis and starvation ketosis. However, isolated vomiting can also cause a metabolic alkalosis through loss of gastric acid. In addition, isolated diarrhoea can cause a metabolic acidosis through loss of bicarbonate in the stool, but the child who can increase oral intake to keep pace with the diarrhoeal losses may not actually be dehydrated. Despite these confounding factors, it has been shown that serum bicarbonate is significantly lower in children with moderate or severe dehydration (mean 14.5 mEq L–1 and 10.3 mEq L–1) than in children with mild dehydration (mean 18.9 mEq L–1).3 Raised serum urea levels have also been thought to reflect dehydration, but with even less evidence.

Differential diagnosis

Features of concern to suggest the possibility of other cause include:

See Chapter 7.8 on vomiting, for more details on differential diagnosis.

Treatment

Mildly dehydrated

The essential things to ensure are:

Appropriate oral fluids

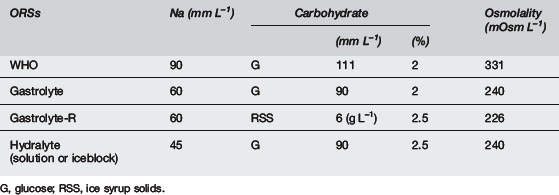

The WHO ORS has a sodium concentration of 90 mmol L–1. In developed countries with non-cholera diarrhoea, it is generally thought that 90 mmol L–1 is a little high, as non-cholera gastroenteritis does not result in the same sodium losses that are seen in cholera. Many different ORSs with varying sodium concentrations have been developed. It has been shown6 that water absorption across the lumen of the human intestine is maximal using solutions with a sodium concentration of 60 mmol L–1 and this is the concentration recommended by the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition.7 Studies have also shown that hypo-osmolar solutions are most effective at promoting water absorption.8–10

Studies have also examined rice-based ORSs and their effect on stool output and duration of diarrhoea when compared with glucose-based ORSs. Rice-based ORSs appear to have benefits in cholera diarrhoea but not in non-cholera diarrhoea.11

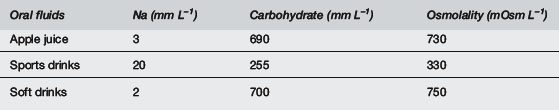

The composition of various ORSs and other fluids is shown in Tables 7.12.4 and 7.12.5. Fruit juices and soft drinks are inappropriate because of the minimal sodium content and the excessive glucose content and hence excessive osmolality. Diluting these solutions will not address the grossly inadequate sodium content, nor will it result in an optimal glucose concentration or osmolality. Sports drinks are also inappropriate, with too low sodium levels and too high glucose levels and osmolalities.

Refeeding

Moderately dehydrated

Some children who present to EDs with gastroenteritis are moderately dehydrated. These children can be rehydrated in several ways. Some are successfully rehydrated with oral fluids alone, as previously described. Some fail this and require additional intervention. Increasing numbers of hospitals in developed countries are using oral rehydration therapy (ORT) via continuous nasogastric infusion.13,14 This is where an ORS is infused continuously down a nasogastric tube with a pump such as a Kangaroo pump. Nasogastric infusions should not be used when the child has an ileus or is comatose. Oral rehydration therapy has been the method of choice in developing countries since the 1970s. However, it has taken longer to become accepted in developed countries. This is despite numerous studies that show that it is as effective as intravenous rehydration but less expensive13–21 and reduces lengths of hospital stay.13

Different regimens are used for continuous nasogastric rehydration. The European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition recommends calculating the fluid deficit and replacing that over 4 hours.22 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mildly dehydrated children receive 50 mL kg–1 over 4 hours and moderately dehydrated children receive 100 mL kg–1 over 4 hours.23 Other regimes recommend a fixed volume, for example 40 mL kg–1 over 4 hours for all mild to moderately dehydrated children followed by a reassessment and retrial of oral fluids.24 This takes into account the tendency for medical officers to overestimate the degree of dehydration2 and the desire to avoid subsequent over-hydration. The important thing to remember is that, whatever regimen is used to rehydrate the child, fluid status should be regularly reassessed.

Intravenous rehydration

The recommended fluid used to rehydrate children with gastroenteritis has changed over recent years. It is now recommended that for children, excluding neonates and infants <3 months of age, 0.9% (150 mmol L–1) saline + 2.5% (or 5%) glucose should be used.25,26 Studies have shown that children with gastroenteritis have inappropriately high levels of antidiuretic hormone and increased incidence and risk of hyponatraemia27 and that low sodium solutions cause hyponatraemia while solutions with a sodium content of 130–154 mmol L–1 are protective.28 As in nasogastric rehydration, it is important to regularly reassess the child’s fluid status. If the child remains on intravenous fluids for >24 hours, it is important to recheck the electrolytes.

Rapid intravenous rehydration: Interest in rapid intravenous rehydration for children with gastroenteritis has emerged in recent years in developed countries. It has long been used in developing countries.29,30 There have been a number of studies in developed countries over the last several years that have looked at this issue24,28,31–33 and shown that this seems to be a safe and effective way to rehydrate children with gastroenteritis who require intravenous therapy. An example of this type of regime is giving 0.9% (150 mmol L–1) saline + 2.5% glucose at 10 mL kg–1 hr–1 for 4 hours.34 It is important that lower sodium-containing fluids are not used.

Other treatments

Antibiotics

Anti-diarrhoeal and anti-emetic medications

Anti-diarrhoeal medications are not indicated in children with gastroenteritis. Most anti-emetic medications are also not indicated. There is little evidence of efficacy and a high incidence of side effects such as dystonic reactions and sedation in infants and young children. There have been some recent studies35–37 that show that ondansetron may have some clinical benefit in this setting by reducing vomiting, but they do not decrease the length of illness and may prolong the diarrhoea.37 Experienced clinicians who wish to use this medication in this setting should generally limit its use to a single dose.

Disposition

In the past, many children were admitted to hospital with gastroenteritis when perhaps they did not need to be.38 With the emergence of ‘Short Stay Wards’ or ‘Emergency Observation Units’, where patients can be admitted to a special area within the ED for a finite time of less than 24 hours, hospital inpatient admission rates for children with gastroenteritis have fallen.24 In these units children can be rehydrated (orally or via rapid nasogastric or intravenous infusion) over a period of a few hours and then sent home after appropriate education and advice. This is provided that the medical officer is confident about the diagnosis of gastroenteritis and that the criteria set out in the ‘mildly dehydrated’ section are fulfilled. Care needs to be taken especially with young infants, as they become dehydrated more rapidly than older children and are more likely to have another diagnosis.

1 World Health Organization. The treatment of diarrhoea: A manual for physicians and other senior health workers. Geneva: WHO, 1995. (WHO/CDR/95.3 Rev 3 10/95)

2 Mackenzie A., Barnes G., Shann F. Clinical signs of dehydration in children. Lancet. 1989;2(8663):605-607.

3 Vega R.M., Avner J.R. A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:179-182.

4 Duggan C., Refat M., Hashem M., et al. How valid are clinical signs of dehydration in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;22:56-61.

5 Gorelick M.H., Shaw K.N., Murphy K.O. Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Paediatrics. 1997;99(5):E6.

6 Hunt J.B., Elliott E.J., Fairclough P.D., et al. Water and solute absorption from hypotonic glucose-electrolyte solutions in human jejunum. Gut. 1992;33:479-483.

7 Booth I., Ferreira R., Desjeux J.F., et al. Recommendation for composition of oral rehydration solutions for the children of Europe. Report of an ESPGAN working group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;14:113-115.

8 Ferreira R.M.C.C., Elliott E.J., Watson A.J.M., et al. Dominant role for osmolality in the efficacy of glucose and glycine-containing oral rehydration solutions: Studies in a rat model of secretory diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr. 1991;81:46-50.

9 Hunt J.B., Thillainayagam A.V., Salim A.F.M., et al. Water and solute absorption from a new hypotonic oral rehydration solution: Evaluation in human and animal perfusion models. Gut. 1992;33:1652-1659.

10 International Study Group on Reduced-osmolarity ORS Solutions. Multicentre evaluation of reduced-osmolarity oral rehydration salts solution. Lancet. 1995;345:282-285.

11 Gore S.M., Fontaine O., Pierce N.F. Impact of rice based oral rehydration solution on stool output and duration of diarrhoea: Meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials. Br Med J. 1992;304:287-291.

12 Walker-Smith J.A., Sandhu B.K., Isolauri E., et al. Recommendations for feeding in childhood gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:619-620.

13 Gremse D.A. Effectiveness of nasogastric rehydration in hospitalised children with acute diarrhoea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:145-148.

14 Mackenzie A., Barnes G. Randomised controlled trial comparing oral and intravenous rehydration therapy in children with diarrhoea. Br Med J. 1991;303:393-396.

15 Sharifi J., Ghavami F., Nowrouzi Z., et al. Oral versus intravenous rehydration therapy in severe gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:856-860.

16 Issenman R.M., Leung A.K. Oral and intravenous rehydration of children. Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:2129-2136.

17 Vesikari T., Isolauri E., Baer M. A comparative trial of rapid oral and intravenous rehydration in acute diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76:300-305.

18 Santosham M., Daum R.S., Dillman L., et al. Oral rehydration therapy of infantile diarrhoea. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1070-1076.

19 Tamer A.M., Friedman L.B., Maxwell S.R.W., et al. Oral rehydration of infants in a large US urban medical center. J Pediatr. 1985;107:14-19.

20 Listernick R., Zieserl E., Davis A.T. Out-patient oral rehydration in the United States. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:211-215.

21 Nager A.L., Wang V.J. Comparison of nasogastric and intravenous methods of rehydration in pediatric patients with acute dehydration. Paediatrics. 2002;109(4):566-572.

22 Sandhu B.K., Isolauri E., Walker-Smith J.A., et al. Early feeding in gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:522-527.

23 American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Practice parameter: The management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. Paediatrics. 1996;97:424-435.

24 Phin S.J., McCaskill M.E., Browne G.J., Lam L.T. Clinical pathway using rapid rehydration in children with gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:343-348.

25 Children’s Hospital Australasia working party. Interim recommendations: Intravenous fluid types for children and adolescents. 2010.

26 National Patient Safety Agency. Reducing the risk of hyponatraemia when administering intravenous fluids to children. 2007. Available from http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/nrls/alerts-and-directives/alerts/intravenous-infusions/ [accessed 15.10.10]

27 Neville K.A., Verge C.F., O’Meara M.W., Walker J.L. High antidiuretic hormone levels and hyponatraemia in children with gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1401-1407.

28 Neville K.A., Verge C.F., Rosenberg A.R., et al. Isotonic is better than hypotonic saline for intravenous rehydration of children with gastroenteritis: a prospective randomised study. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(3):226-232.

29 Slone D., Levin S.E. Hypertonic dehydration and summer diarrhoea. S Afr Med J. 1969;34:209-213.

30 Rahman O., Bennish M.L., Adam A.N., et al. Rapid intravenous rehydration by means of a single polyelectrolyte solution with or without dextrose. J Pediatr. 1988;113:654-660.

31 Reid S.R., Bonadio W.A. Outpatient rapid intravenous rehydration to correct dehydration and resolve vomiting in children with acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 1996;28(3):318-323.

32 Moineau G., Newman J. Rapid intravenous rehydration in the pediatric ED. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1990;6(3):186-188.

33 Brewster D.R. Dehydration in acute gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:219-222.

34 NSW Department of Health. Infants and Children: Acute Management of Gastroenteritis – Clinical practice guideline, 3rd ed.. 2010.

35 Freedman S.B., Adler M., Seshadri R., et al. Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1698-1705.

36 Reeves J.J., Shannon M.W., Fleisher G.R. Ondansetron decreases vomiting associated with acute gastroenteritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):e62.

37 Chubeddu L.X., Trujillo L.M., Talmaciu I., et al. Antiemetic activity of ondansetron in acute gastroenteritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(1):185-191.

38 Elliott E.J., Backhouse J.A., Leach J.W., et al. Pre-admission management of acute gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996;32:18-21.

39 Guandalini S., Pensabene L., Zikri M.A., et al. Lactobacillus GG administered in oral rehydration solution to children with acute diarrhoea: A multicentre European trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:54-60.