Chapter 28 Gastroenteritis

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

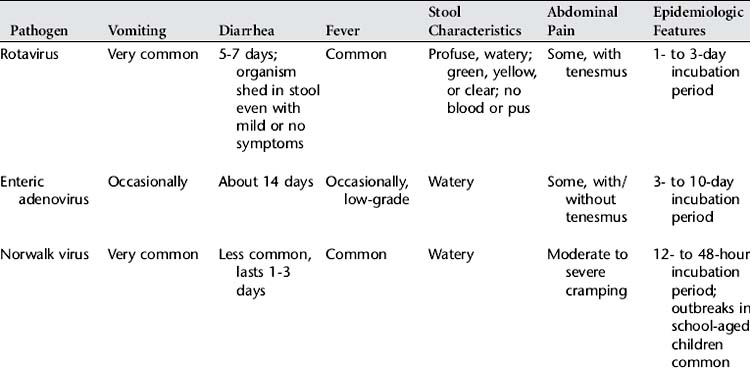

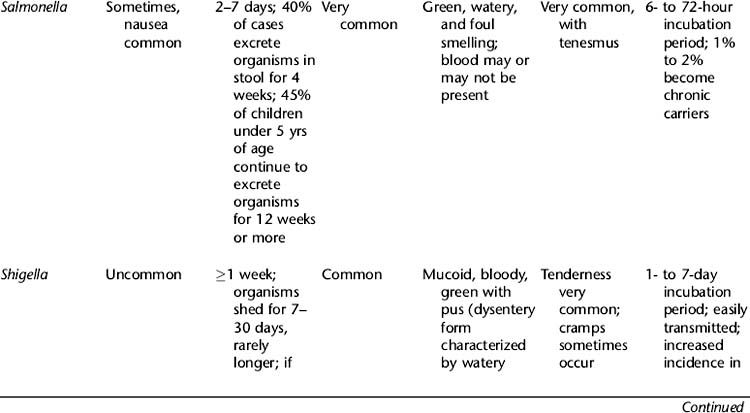

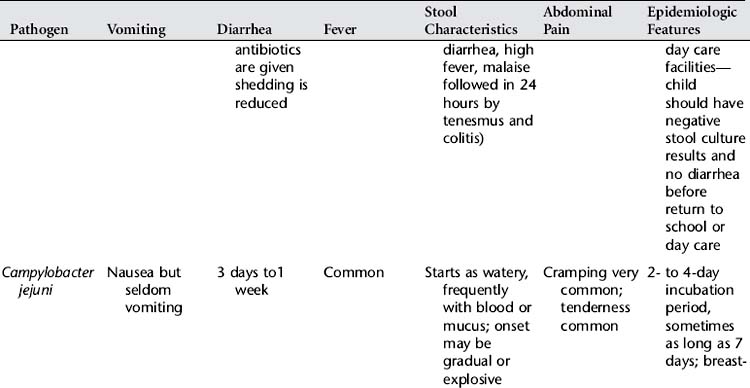

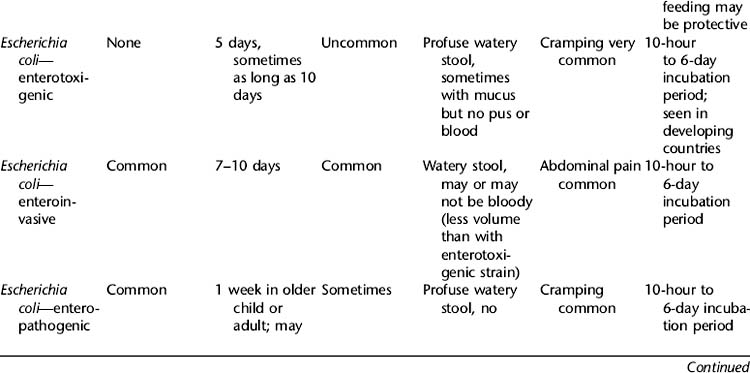

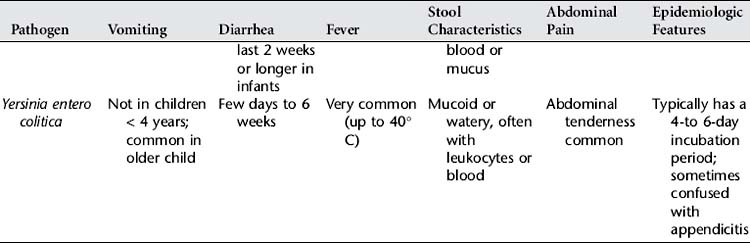

Gastroenteritis or acute infectious diarrhea is defined as inflammation of the mucous membranes of the stomach and intestines. Acute gastroenteritis is characterized by diarrhea and, in some cases, vomiting; the resulting fluid and electrolyte losses lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. The major causes of acute gastroenteritis include viruses (rotavirus, enteric adenovirus, Norwalk virus, and others), bacteria or their toxins (Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, Yersinia, and others), and parasites (Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium) (Table 28-1). These pathogens cause illness by infecting the cells, producing enterotoxins or cytotoxins that damage the cells, or adhering to the walls of the intestines. In acute gastroenteritis, the small intestine is the most often affected.

Rotavirus, which is the most common causative agent for gastroenteritis, has an incubation period of 24 to 48 hours. Vomiting is the first symptom in 80% to 90% of patients, followed by low-grade fever and voluminous watery diarrhea. Diarrhea usually lasts 4 to 8 days but may last longer. In young infants or immunocompromised patients, rotavirus acute gastroenteritis may be preceded by mild upper respiratory infection (URI) symptoms.

Acute gastroenteritis is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, from person to person or through contaminated water and food supplies. Spending time in day-care facilities increases the risk for gastroenteritis, as does travel to developing countries. Replacement of fluid and electrolyte insufficiency and ongoing losses is critical, especially for small infants. Metabolic acidosis results from bicarbonate loss in the stool, ketosis from poor intake, and lactic acidemia from hypotension and hypoperfusion. Most infections are self-limited, and prognosis is favorable with treatment. Malnourished children may have more severe infections and take longer to recover.

INCIDENCE

1. Acute viral gastroenteritis is the second most common condition affecting children (the common cold is the first).

2. About half of all cases of gastroenteritis occur during a 3- to 4-month winter peak.

3. The highest rate of illness occurs in children between 3 months and 2 years of age.

4. Viral agents are thought to account for 80% of reported community diarrhea and repeated exposures to agents like rotavirus. Rotavirus is the causative agent in approximately 50% of hospital admissions for acute gastroenteritis. The seasonal peak occurs approximately between November and May each year, with prevalence in the United States beginning in the Southwest and spreading to the Northeast. Between 5% and 10% of admissions result from infection with enteric adenoviruses, and another 15% are due to bacterial causes.

5. Breast-fed infants contract gastroenteritis less often than formula-fed infants; maternal antibodies to some enteric pathogens are transferred in breast milk.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

1. Loose consistency of stools (diarrhea) with increased frequency, with and/or without blood or mucus

2. Anorexia, nausea, and/or vomiting (usually of short duration)

3. Fever (may or may not be present)

4. Abdominal cramping, tenesmus

5. Evidence of dehydration such as dry mucous membranes, sunken fontanelle in infants

LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

1. Fecal occult blood test—to check for presence of blood (more common with bacterial origin)

2. Stool evaluation for volume, color, consistency, presence of mucus or pus

3. Complete blood count with differential

4. Enzyme immunoassay antigen tests—to confirm presence of rotavirus

5. Stool culture (if hospitalized, pus is present in stool, or course of diarrhea is prolonged)—to determine pathogen

6. Stool evaluation for ova and parasites; performed 3 times, 24 hours apart

7. Duodenal aspiration (if G. lamblia is suspected)

8. Urinalysis and culture (specific gravity increases with dehydration; Shigella organisms are shed in urine)

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

When the child is mildly dehydrated, rehydration may be accomplished orally on an outpatient basis with commercially available oral rehydration solutions (ORSs such as Pedialyte, Ricelyte). ORSs boost and advance the reabsorption of sodium and water. Oral rehydration fluids are given frequently, in small volumes (5 to 30 ml), even in the event of vomiting. Breast-fed infants can continue to be nursed during periods of diarrhea. In the case of severe dehydration, the child is admitted for intravenous (IV) therapy to correct dehydration. The amount of dehydration is calculated, and fluid is replaced over 24 hours, at the same time that maintenance fluids are given.

When shock is present, fluid resuscitation commences immediately (20 ml/kg of normal saline solution or lactated Ringer’s solution; repeat if needed). In these cases, when rapid peripheral IV access is unsuccessful, the intraosseous route may be used for emergency fluid administration in a child younger than 6 years of age. When systemic perfusion has been improved, correction of existing dehydration is begun.

Once rehydration is completed, the diet may be advanced to a regular diet of easily digested foods. Foods best tolerated are complex carbohydrates (rice, wheat, cereals, potatoes, and bread), yogurt, lean meats, fruits, and vegetables. The classic BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast or tea), although well tolerated, is low in protein, fat, and calories for energy. Ideal foods to encourage are ones that contain complex carbohydrates (rice, baked potatoes, noodles, crackers, toast, cereals). Juices, sports beverages, and soft drinks should be avoided. Water should not be the only vehicle of oral fluids.

Feeding and oral administration of rehydration fluids have reportedly decreased the duration of diarrhea. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention all recommend oral rehydration therapy (ORT) as the treatment of choice for most cases of dehydration caused by diarrhea. Early return to normal oral feedings is important, especially in cases of preexisting malnutrition.

Administration of antiemetics and antispasmodics is generally not recommended. Neither is the use of antibiotics indicated in most cases, because bacterial and viral gastroenteritis is self-limited. Antibiotics are used, however, in the treatment of diseases caused by Shigella organisms, E. coli, Salmonella organisms (when sepsis or localized infection is present), and G. lamblia. Use of antibiotics may increase the duration of the carrier state in Salmonella infections.

NURSING INTERVENTIONS

1. Promote and monitor child’s fluid and electrolyte balance.

2. Prevent further gastrointestinal tract irritability.

3. Prevent skin irritation and breakdown.

4. Follow universal precautions and/or enteric precautions to prevent transmission of infection (refer to institution’s policies and procedures).

5. Provide for child’s developmental needs during hospitalization.

Discharge Planning and Home Care

American Academy of Pediatrics. Pickering LK, ed. 2003 Red book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 26, Elk Grove Village, Ill: The Academy, 2000.

Dennehy PH. Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(10):S103.

Hay WW, et al. Current pediatric diagnosis and treatment, ed 17. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Larson CE. Safety and efficacy of oral rehydration therapy for the treatment of diarrhea and gastroenteritis in pediatrics. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26(2):177.

Perlstein PH, et al. Implementing an evidence-based acute gastroenteritis guideline at a children’s hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(1):20.

Wong DL, et al. Maternal child nursing care, ed 3. St. Louis: Mosby, 2006.