Chapter 4 Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

AETIOLOGY

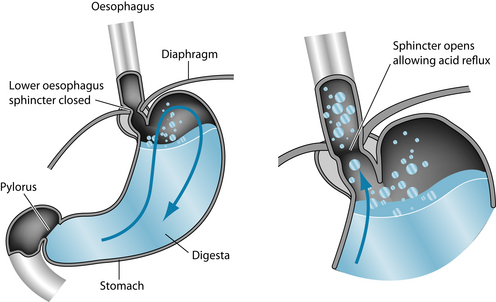

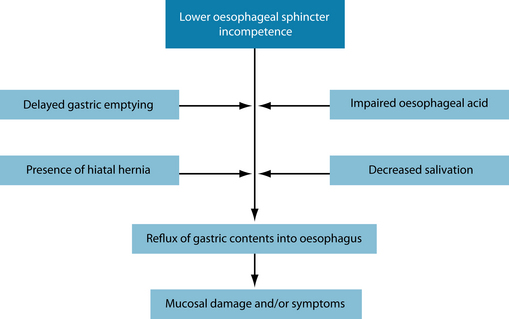

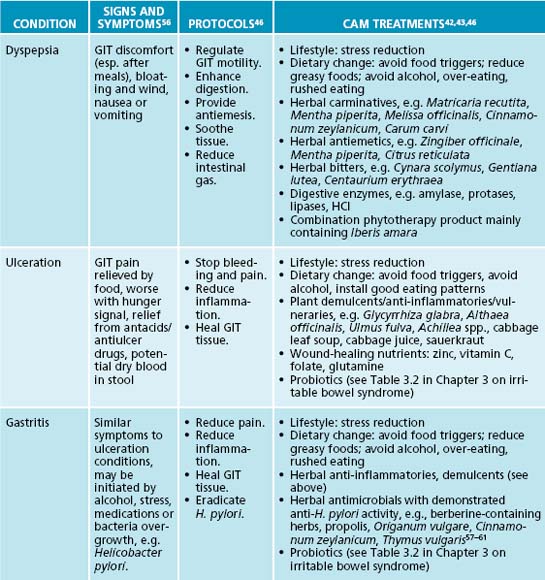

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is commonly encountered in clinical practice. Recent research has estimated the prevalence at 10–20% in Western nations.1 GORD has been defined as ‘a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications’.2 Signs and symptoms of GORD result primarily from the recurrent reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus (Figure 4.1). The pathogenesis of GORD is complex and multifactorial with a number of mechanisms appearing to be involved (Figure 4.2):

RISK FACTORS

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

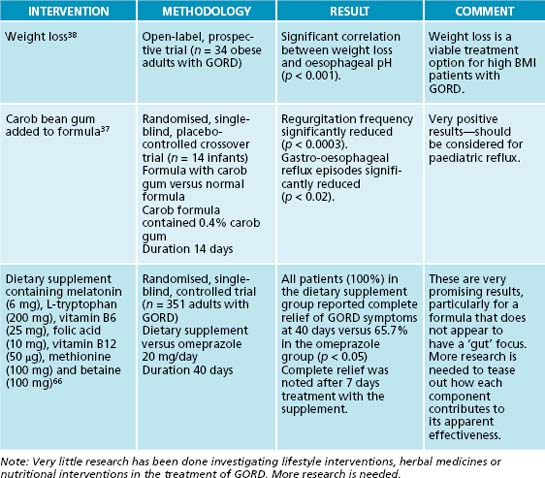

Conventional treatment aims to reduce the symptoms of GORD and reduce oesophageal damage through the use of antisecretory therapies, such as proton pump inhibitors or histamine type 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs). Although these agents have been found to be effective in reducing the oesophageal symptoms of GORD and, to a lesser extent, extraoesophageal symptoms,26 their use is also associated with significant side effects and risks. Common adverse events of antisecretory therapies include diarrhoea, nausea, abdominal pain and headaches.27 Longer-term use of anti-secretory drugs is associated with increased risk of gastroenteritis,28 pneumonia,29 spinal fracture30 and vitamin and mineral malabsorption.31,32 More recently, the surgical procedure laparoscopic fundoplication has been advocated in the treatment of GORD.

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

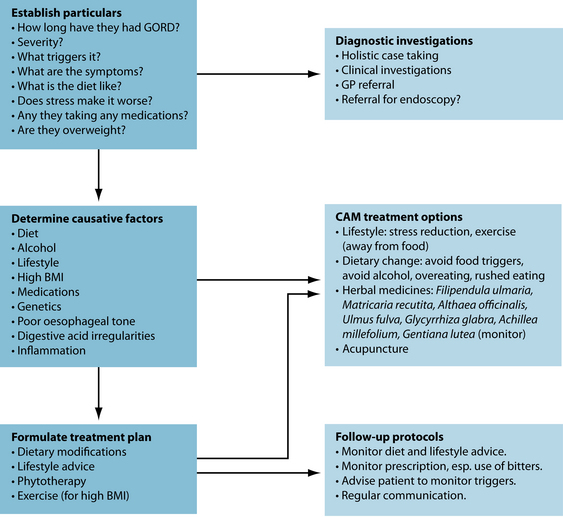

The naturopathic protocols adopted to treat GORD usually focus on dietary and lifestyle modifications, in addition to botanical treatments. After relieving symptoms, the aim is to initially identify any factors that contribute to GORD and remove these triggers. If inflammation, ulceration or poor motility/sphincter tone is present, herbal or nutritional prescription may be of benefit.

Relieve symptoms

Relief of heartburn is paramount in the management of GORD. Gastrointestinal demulcents are typically very effective in providing prompt relief of heartburn symptoms (usually within minutes of ingestion). Effective demulcents include Althaea officinalis radix, Ulmus fulva cortex and Glycyrrhiza glabra.44 Gastrointestinal demulcents are most effective when administered in powdered form—mixed into a little water or apple juice to form a slurry or gruel. Tablets and capsules will be significantly less effective. Demulcents can be used ‘on demand’ or taken after meals and/or before bed for a preventative effect.

Eliminate exacerbating factors

Dietary factors

The naturopathic axiom tolle causum (‘treat the cause’) is particularly relevant to the management of GORD. While herbal demulcents can relieve heartburn symptoms effectively and promptly, their use, in some respects, is only palliative if patients continue to indulge in dietary factors known to exacerbate their condition. Avoidance of foods and drinks known to precipitate reflux episodes (for example, chocolate, alcoholic beverages, caffeinated beverages and fatty foods) is an important therapeutic strategy that may produce excellent clinical outcomes (see Chapter 5 on food intolerance/allergy),33 although it should be noted that an ‘evidence-based review’ of dietary changes was inconclusive due to insufficient research.18 The authors did, however, note that there is a definitive link in some sufferers of GORD with food and alcohol, as physiological evidence has demonstrated decreased LOS tone.

Other recommendations, such as taking time when eating, consuming smaller meals and avoiding fluid consumption with meals (both should decrease gastric distension) and chewing food adequately, are traditional naturopathic recommendations.34 Chewing food as thoroughly as possible is a traditional recommendation which may result in improved salivary gland function over time and, hence, improved oesophageal acid clearance. Changing the evening meal time to earlier in the evening (at least 3–4 hours before bedtime) can also be helpful.35

In infants and toddlers with GORD, a dairy-free diet should be implemented. If they are formula-fed, the mother should be encouraged to relactate. The use of an extensively hydrolysed whey formula is the next best option. Soy and goat’s milk formulas should be avoided as they share a significant amount of cross-reactivity with cow milk proteins. There have also been a number of studies demonstrating the efficacy of carob bean powder (Ceratonia siliqua) as a formula additive.36,37 Carob powder has been found to significantly decrease the severity and frequency of vomiting in infants with GORD, as well as increasing weight gain.36 If the infant is exclusively breastfed, then the mother should be placed on a dairy-free diet, as small, but clinically significant, amounts of dairy proteins do appear in the breast milk.

Lifestyle factors

In addition to the dietary factors discussed above, lifestyle factors such as obesity and smoking should be addressed. Weight loss has been shown in some research to result in reduced reflux episodes and should be encouraged in all overweight and obese patients.38 Cessation of smoking could be recommended for a number of compelling reasons, not the least of which is its effect on oesophageal reflux. Short-term studies (of 24–48 hours duration) have not consistently found a reduction in reflux episodes after smoking cessation.39,40 However, no longer-term studies have yet been performed and, in light of smoking’s well-known adverse effects, GORD patients who smoke should be encouraged to give up. Herbal thymoleptics, anxiolytics and adaptogens could play an important supportive role in this process (see the section on the nervous system).

Raising the head of the bed is another easy-to-implement lifestyle intervention that has demonstrated beneficial effects in GORD.18 This recommendation is based on the theory that acidic stomach contents will be more likely to reflux when patients are lying flat. Research has, thus far, mostly supported this theory, with intervention trials finding reduced frequency of reflux episodes, shorter reflux episodes and fewer reflux symptoms when bed heads were raised (one trial raised the head by 28 cm).41

Decrease oesophageal inflammation and promote oesophageal healing

The reduction of oesophageal inflammation and the promotion of oesophageal healing will help reduce the vicious circle of GORD. As previously discussed, inflammation is a common occurrence in GORD. Demulcents (as discussed above), anti-inflammatory and vulnerary herbs may soothe the tissue and enhance healing. Useful anti-inflammatory phytomedicines for the digestive system include Filipendula ulmaria, Glycyrrhiza glabra and Matricaria recutita, while vulnerary herbal medicines traditionally used to help heal the upper gastrointestinal tract include Althaea officinalis, Ulmus fulva, Calendula officinalis, Symphytum officinale and Aloe barbadensis.42,43 Given that alcohol is a common reflux exacerbating factor, teas are probably the preferred method of administration.

Given the role of free radicals in reflux-induced oesophageal inflammation,14 the promotion of antioxidant defences is a worthwhile, but as yet under-researched, therapeutic approach. The incorporation of brightly coloured fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains into the diet should be encouraged (see the food nutrient chart in Appendix 4).

WHAT ABOUT HYPOCHLORHYDRIA AND DIGESTIVE BITTERS?

At this point in time, however, there is little hard evidence to support either theory.

Bitters increase saliva secretion,47 speed gastric emptying,48 and exhibit mucosal protective activity.49 Caution should be used in their application, however, as any increase in gastric acidity could significantly aggravate GORD symptoms.

Tone the lower oesophageal sphincter

A traditional naturopathic focus of treating GORD is to improve the tone of the smooth muscle of the LOS, thereby enhancing its capacity to hold gastrointestinal contents in the stomach. Poor LOS tone may be potentially improved by the use of tannin-rich herbs, which provide astringency and increased tissue tone, in addition to reducing inflammation.44 Hydrolysable tannin constituents (higher molecule weight tannins) primarily affect astringency.44 Botanicals that contain these tannins include Geranium maculatum, Achillea millefolium, Calendula officinalis, Hamamelis virginiana and Agrimonia eupatorium.45 The naturopath should be aware that long-term use or high doses of tannins may impede digestion. A prudent approach is to co-prescribe a herbal medicine with a bitter principle to stimulant digestion and to provide an adjuvant anti-inflammatory effect. However, to complicate matters, the use of bitters should be monitored carefully as this may worsen some people’s GORD.46

Prevent oesophageal cancer

One of the more serious complications of GORD is the development of Barrett’s oesophagus, a metaplastic change of the lining of the oesophagus that is associated with an increased risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma.50 Preventing the development of Barrett’s oesophagus and preventing the change of Barrett’s oesophagus to adenocarcinoma should be major naturopathic treatment aims. Preventing reflux episodes, reducing oesophageal inflammation and promoting mucosal healing using the strategies discussed above will be part of this approach. Reducing oxidative stress is an additional approach to this issue, as research has found patients with Barrett’s oesophagus to have lower plasma concentrations of antioxidants (selenium, vitamin C, β-cryptoxanthine and xanthophyll) than GORD patients without Barrett’s oesophagus.51 This can best

be done by encouraging the consumption of antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables, legumes and whole grain products on a daily basis.

Epidemiological research has found an inverse relationship between dietary intake of zinc and incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma52 and animal models have found zinc deficiency to be a significant contributing factor to the development of Barrett’s oesophagus.53 In light of this research, zinc supplementation may also be warranted in GORD sufferers in an attempt to prevent the development of Barrett’s oesophagus (see Chapter 29 on cancer for overarching protocols and interventions).

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Medical referral

Diagnosis of GORD is typically made clinically, based on the presence of the classic symptoms—a burning feeling rising from the stomach or lower chest up towards the neck (heartburn) and/or the effortless return of stomach contents into the pharynx (regurgitation). The diagnosis is usually confirmed by its good response to therapy. In the conventional medicine, this equates to antacids, proton pump inhibitors or histamine type 2 receptor antagonists. In naturopathic medicine, this could equate to a short trial of antacids, but more probably a trial of gastrointestinal demulcents. If the patient presents with the classic symptom picture and responds to demulcent therapy, that confirms the diagnosis. If alarm signs and symptoms are present (for example, weight loss, dysphagia, an epigastric mass upon examination, anaemia or signs of internal bleeding), then patients should be referred for further investigation (endoscopy). If the patient presents with the classic symptoms of GORD but does not respond to treatment, then referral is also recommended.26,54

Acupuncture

In a recently published clinical trial, the efficacy of acupuncture was compared to doubling the dose of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in patients unresponsive to the standard dose of a PPI. Subjects were randomised to receive either 10 acupuncture sessions over a 4-week period in combination with their original PPI or the same PPI at double the daily dose. At the end of a 4-week treatment period, subjects in the acupuncture group

had significant decreases in daytime heartburn, night-time heartburn, acid regurgitation and dysphagia compared to baseline versus no significant change in the double dose PPI group.55 In subjects unresponsive to initial naturopathic therapy, referral to a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner may be warranted.

Example treatment

Upon analysing her diet, it was found to fit the ‘standard Australian diet’ (SAD)—low in fruits, vegetables and whole grains. In terms of GORD risk factors, she consumed caffeine-containing beverages with each meal, ate lots of fatty foods, consumed chocolate, wine and coffee most evenings after dinner, and ate snacks just before retiring most evenings. To address these GORD risk factors, she was advised not to have any beverages with her meals and to drink fluids only between meals (≥ 1 hr before or ≥ 2 hr after), to switch from full-cream milk to skim, to eliminate all caffeinated and alcoholic beverages, and to avoid other foods known to decrease LOS pressure or worsen GORD symptoms (chocolate, tomatoes and tomato products, and peppermint lollies). She was also advised to eat her evening meals earlier in the evening (prior to 7 p.m.), eat smaller meals in general and advised not to snack after 7 p.m. To help prevent the development of Barrett’s oesophagus, she was advised to consume more fruit daily (three to five pieces), vegetables (five serves daily) and whole grains.

Herbal formula

| Achillea millfolium 1:2 | 35 mL |

| Matricaria recutita 1:2 | 35 mL |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra 1:1 | 25 mL |

| Gentiana lutea 1:2 | 5 mL |

| 5 mL each evening as required | 100 mL |

Filipendula ulmaria: 2–3 cups daily between meals using 1 heaped tablespoon per cup

Her BMI was within normal range,21 so there was no need to recommend weight loss. Her incidental exercise levels were quite high—she worked most days each week on her garden acreage—and also walked 3 km at least four times each week.

A herbal tincture was prescribed to acutely relieve her reflux symptoms. Achillea millefolium was prescribed in the tincture for its tannic, phenolic and volatile oil compounds that may increase LOS tone and reduce inflammation.62 Matricaria recutita and Glycyrrhiza glabra will provide a topical anti-inflammatory activity that should soothe the inflamed oesophageal in combination.42,63,64 Glycyrrhiza glabra has the additional benefit of helping to heal the oesophageal mucosa.46 The use of Gentiana lutea as a bitter to enhance digestive activity needs to be monitored as it may potentially cause GORD to be worsened in some individuals.46,65 As indicated in the case, her digestion seems insufficient (bloating and halitosis); hence the use of a bitter may be warranted. Gastrointestinal demulcents (powdered Ulmus fulva and Althaea officinalis) were prescribed to relieve the reflux symptoms and to help protect and heal the oesophageal mucosa.42 Filipendula tea was prescribed to help decrease the oesophageal inflammation and to heal the mucosa. A herbal tincture was prescribed to acutely relieve her symptoms.

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

KEY POINTS

American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392-1413.

Baille N. Indigestion: antacids, bitters, digestive enzymes; when to use what? Aust J Med Herbalism. 2002;14(4):151-157.

Kaltenbach T., et al. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965-971.

1. Dent J., et al. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717.

2. Vakil N., et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920.

3. Cadiot G., et al. Multivariate analysis of pathophysiological factors in reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1997;40:167-174.

4. Dent J., et al. Mechanisms of lower oesophageal sphincter incompetence in patients with symptomatic gastrooesophageal reflux. Gut. 1988;29:1020-1028.

5. Anggiansah A., et al. Oesophageal motor responses to gastro-oesophageal reflux in healthy controls and reflux patients. Gut. 1997;41:600-605.

6. Stanciu C., Bennett J.R. Oesophageal acid clearing: one factor in the production of reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1974;15:852-857.

7. Stacher G., et al. Gastric emptying: a contributory factor in gastro-oesophageal reflux activity? Gut. 2000;47:661-666.

8. Holloway R.H., et al. Gastric distention: a mechanism for postprandial gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:779-784.

9. Urita Y., et al. Salivary gland scintigraphy in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15:141-145.

10. Van Niewenhove Y.V., et al. Clinical relevance of laparoscopically diagnosed hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1093-1098.

11. Van Herwaarden M.A., et al. Excess gastroesophageal reflux in patients with hiatus hernia is caused by mechanisms other than transient LES relaxations. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1439-1446.

12. Kahrilla P.J., et al. The effect of hiatus hernia on gastro-oesophageal junction pressure. Gut. 1999;44:476-482.

13. Jones M.P., et al. Hiatal hernia size is the dominant determinant of esophagitis presence and severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1711-1717.

14. Wetscher G.J., et al. Reflux esophagitis in humans is mediated by oxygen derived free radical. Am J Surg. 1995;170:552-557.

15. Oh T.Y., et al. Oxidative stress is more important than acid in the pathogenesis of reflux oesophagitis in rats. Gut. 2001;49:364-371.

16. Salvatore S., Vandenplas Y. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow milk allergy: is there a link? Pediatrics. 2002;110:972-984.

17. Usai P., et al. Effect of gluten-free diet on preventing recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease-related symptoms in adult celiac patients with nonerosive reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;23:1369-1372.

18. Kaltenbach T., et al. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):965-971.

19. Nocon M., et al. Lifestyle factors and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux – a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:169-174.

20. Watanabe Y., et al. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japanese men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:807-811.

21. Kahrilas P.J., Gupta R.R. Mechanisms of acid reflux associated with cigarette smoking. Gut. 1990;31:4-10.

22. Rey E., et al. Influence of psychological distress on characteristics of symptoms in patients with GERD: the role of IBS comorbidity. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;54(2):321-327.

23. Bradley L.A., et al. The relationship between stress and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux: the influence of psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:11-19.

24. Cameron A.J., et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:55-59.

25. Castell D.O., et al. Review article: the pathophysiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – oesophageal manifestations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 9):14-25.

26. American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392-1413.

27. Davies M., et al. Safety profile of esomeprazole: results of a prescription monitoring study of 11,595 patients in England. Drug Saf. 2008;31:313-323.

28. Canani R.B., et al. Therapy with gastric acidity inhibitors increases the risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:817-820.

29. Gulmez S.E., et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:950-955.

30. Elaine W.Y., et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of bone loss and fracture in older adults. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;83(4):251-259.

31. Ruscin J.M., et al. Vitamin B(12) deficiency associated with histamine(2)-receptor antagonists and a proton pump inhibitor. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:812-816.

32. Kuipers M.T., et al. Hypomagnesaemia due to use of proton pump inhibitors – a review. Neth J Med. 2009;169:169-172.

33. Semeniuk J., Kaczmarski M. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in children and adolescents with regard to food intolerance. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:321-326.

34. Benjamin H. Everybody’s guide to nature cure, 2nd edn. London: Health for All Pub. Co.; 1961.

35. Duroux P., et al. Early dinner reduces nocturnal gastric acidity. Gut. 1989;30:1063-1067.

36. Vivatvakin B., Buachum V. Effect of carob bean on gastric emptying time in Thai infants. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12:193-197.

37. Wenzl T.G., et al. Effects of thickened feeding on gastroesophageal reflux in infants: a placebo-controlled crossover study using intraluminal impedance. Pediatrics. 2003;111:355-359.

38. Fraser-Moodie C.A., et al. Weight loss has an independent beneficial effect on symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients who are overweight. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:337-340.

39. Schindlbeck N.E., et al. Influence of smoking and esophageal intubation on esophageal pH-metry. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1994-1997.

40. Kadakia S.C., et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on gastroesophageal reflux measured by 24-h ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1785-1790.

41. Stanciu C., Bennett J.R. Effects of posture on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Digestion. 1977;15:104-109.

42. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

43. Blumenthal M., et al. The ABC clinical guide to herbs. Austin: American Botanical Council; 2004.

44. Pengelly A. The constituents of medicinal plants, Vol 2. Glebe: NSW: Fast Books; 1997.

45. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs: herbal formulations for the individual patient. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

46. Baille N. Indigestion: indigestion: antacids, bitters, digestive enzymes: when to use what? Aust J Med Herbalism. 2002;14(4):151-157.

47. Borgia M., et al. Pharmaco-logical activity of an herbal extract: controlled clinical study. Curr Ther Res. 1981;29:525-536.

48. Metugriachuk Y., et al. Effect of a phyto-compound on delayed gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia: a randomized-controlled study. J Dig Dis. 2008;9:204-207.

49. Niiho Y., et al. Gastroprotetive effects of bitter principles isolated from gentian root and swertia herb on experimentally-induced gastric lesions in rats. J Nat Med. 2006;60:82-88.

50. Shaheen N., Ransohoff D.F. Gastroesophageal reflux, Barrett esophagus and esophageal cancer. JAMA. 2002;287:1972-1981.

51. Clements D.M., et al. A study to determine plasma antioxidant concentrations in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:490-492.

52. Chen H., et al. Nutrient intakes and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and distal stomach. Nutr Cancer. 2002;42:33-40.

53. Guy N.C., et al. A novel dietary-related model of esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus, a premalignant lesion. Nutr Cancer. 2007;59:217-227.

54. DeVault K.R., Castell D.O. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200.

55. Dickman R., et al. Clinical trial: acupuncture vs. doubling the proton pump inhibitor dose in refractory heartburn. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1333-1344.

56. Kumar P., Clark M., editors. Clinical medicine, 5th edn., London: W.B. Saunders, 2002.

57. Tabak M., et al. In vitro inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by extracts of thyme. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;80:667-672.

58. Tabak M., et al. Cinnamon extracts’ inhibitory effect on Helicobacter pylori. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67:269-277.

59. Chung J.G., et al. Inhibitory actions of berberine on growth and arylamine N-acetyltransferase activity in strains of Helicobacter pylori from peptic ulcer patients. Int J Toxicol. 1999;18:35-40.

60. Stamatis G., et al. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Greek herbal medicines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;88:175-179.

61. Nostro A., et al. Effects of combining extracts (from propolis or Zingiber officinale) with clarithromycin on Helicobacter pylori. Phytother Res. 2006;20:187-190.

62. Nemeth E., Bernath J. Biological activities of yarrow species (Achillea spp.). Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(29):3151-3167.

63. Aly A.M., et al. Licorice: a possible anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcer drug. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2005;6(1):E74-E82.

64. Asl M.N., Hosseinzadeh H. Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother Res. 2008;22(6):709-724.

65. Aktay G., et al. Hepatoprotective effects of Turkish folk remedies on experimental liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73(1–2):121-129.

66. Pereira R.S. Regression of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms using dietary supplementation with melatonin, vitamins and amino acids: comparison with omeprazole. J Pineal Res. 2006;41:195-200.