108 Gastritis and Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Etiology and Pathogenesis

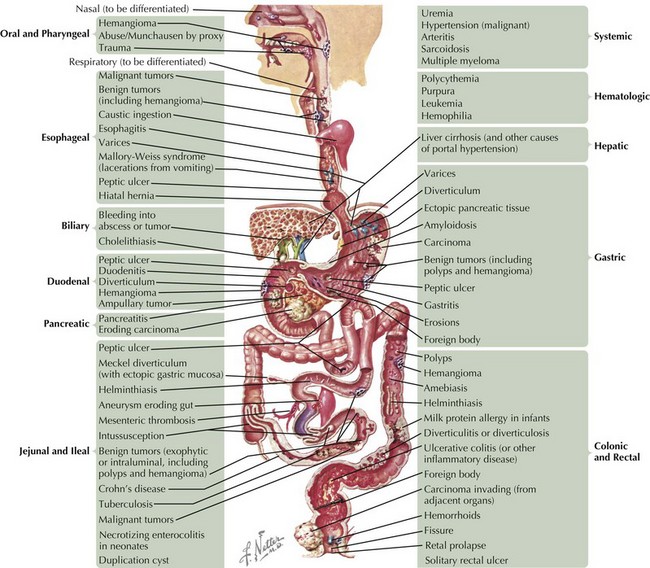

The causes of GI bleeding are diverse (Figure 108-1). Although the sheer number of causes may seem intimidating, grouping them into pathophysiologic categories aids in constructing a differential diagnosis. Note that underlying disorders of coagulation (e.g., hemophilias, vitamin K deficiency in neonates) and hepatic dysfunction (caused by the liver’s role in producing coagulation factors) can exacerbate any of these causes.

Mucosal Erosion

Inflammation

Disruption of mucosal integrity may occur in disorders that promote the recruitment of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and neutrophils, which injure the epithelium by direct cell-to-cell contact or via secreted immunologic factors, such as cytokines. Examples include autoimmune enteropathy and eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Another important example is inflammatory bowel disease, a complex autoimmune disease that encompasses Crohn’s disease, which can cause full-thickness inflammation anywhere along the GI tract, and ulcerative colitis, which causes mucosal ulcerations in the colon (see Chapter 110). Children who have undergone bone marrow transplant may experience a form of rejection called graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). When it affects the GI tract, GVHD causes diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, and GI bleeding. Certain immunodeficiencies, such as common variable immunodeficiency, precipitate inflammation because of dysregulated immunity that leads to autoimmune responses (see Chapter 21).

Infection

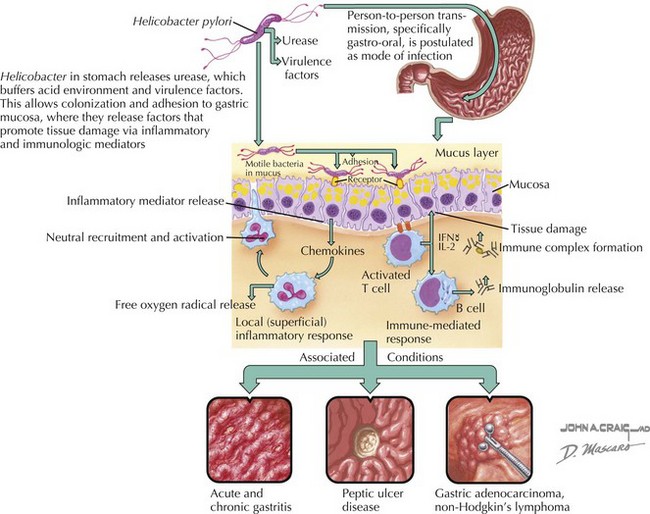

Infections disrupt mucosal integrity by direct cytotoxicity and/or by promoting inflammation. For example, herpes simplex virus is known to cause florid esophagitis, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, with nearly one-third of these patients experiencing an acute upper GI bleed. Additionally, infections may elicit specific peculiar responses. For example, cytomegalovirus is occasionally associated with massive gastric epithelial proliferation leading to a hypertrophic gastropathy called Menetrier’s disease. This causes protein wasting (including coagulation factors) from the leaky mucosa, as well as a higher risk of mucosal erosion and bleeding. Helicobacter pylori is perhaps the most infamous of the infectious causes of gastritis and duodenitis because of its chronicity, high prevalence (especially in certain populations of children, such as immigrants, the poor, and those attending daycare centers), its associations with peptic ulcers and adenocarcinoma of the stomach and duodenum, and its resistance to eradication (Figure 108-2).

Vascular Abnormalities

Congenital vascular defects may result in fragile vascular arrangements vulnerable to erosive and mechanical insults. Whereas hemangiomas represent proliferative vessel abnormalities that may regress, true malformations (including disorders such as arteriovenous malformations, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, and Osler-Rendu-Weber syndrome) are nonproliferative and do not regress. Processes that compromise the full thickness of bowel, such as Crohn’s disease and bowel surgery, may result in vessel-to-bowel fistulas associated with significant bleeding. Vasculitides, such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura, may result in occlusion of mesenteric vessels and intestinal ischemia (see Chapter 28).

Clinical Presentation

The clinician’s first priority is to establish the patient’s stability; the initial impression can provide valuable clues. Pallor, lethargy, and diaphoresis are all immediately concerning signs of significant blood loss. However, the absence of these signs in a seemingly well-appearing individual with a history of hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia should not automatically comfort the clinician. Indeed, tachycardia combined with normal blood pressure for age could indicate compensated shock (see Chapter 2). The most definitive physical examination indicator of significant blood loss is orthostatic hypotension, defined as a decrease in systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg within 3 minutes of standing.

The clinician should then focus on addressing several key questions:

Evaluation and Management

Determine High-Risk Historical Factors

Initial Management in the Emergency Department

Any patient with evidence of significant bleeding should receive supplemental oxygen, be placed on constant hemodynamic monitoring, and have at least two large-bore intravenous catheters placed. If rapid hemodynamic resuscitation is indicated, isotonic fluids may be required, but blood is the preferred product if there is clear evidence of significant blood loss (see Chapter 2).

Additional Evaluations

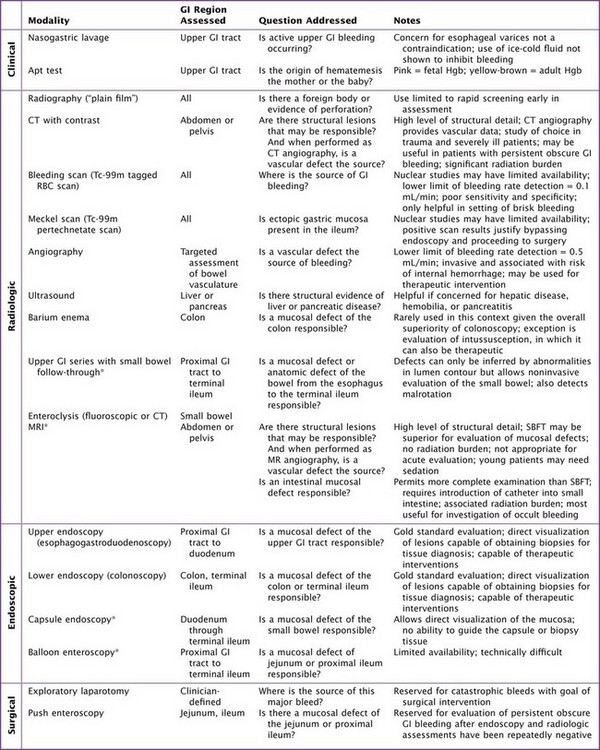

Radiologic, endoscopic, and surgical evaluations are summarized in Table 108-1. The approach depends on the bleeding acuity and the setting in which the patient is seen. In general, when the source of bleeding is unclear, the goal is to get the patient to endoscopy, in which a fiberoptic camera is inserted into the mouth (upper endoscopy) or anus (lower endoscopy) to directly visualize the intestinal lumen. Endoscopy is the gold standard given its relative safety and its ability to directly visualize the mucosa, obtain tissue for pathologic diagnosis, and potentially administer therapy. However, other diagnostic methods offer particular advantages and may be indispensable to the patient’s assessment before endoscopy. Indeed, certain diagnoses, such as Meckel’s diverticulum or intussusception, may permit bypassing the need for endoscopy, and when bleeding is heavy, the ability to visualize the lumen is severely hampered.

Table 108-1 Diagnostic Modalities for Gastrointestinal Bleeding*

CT, computed tomography; GI, gastrointestinal; Hgb, hemoglobin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. RBC, red blood cell; SBFT, small bowel follow-through; Tc-99m, technetium-99m.

AGA Institute Clinical Practice and Economics Committee. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute Technical Review on Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717.

Gold BD, Colletti RB, Abbott M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31(5):490-497.

Laine L, Takeuchi K, Tarnawski A. Gastric mucosal defense and cytoprotection: bench to bedside. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:41-60.